JARS v41n1 - The Hill That Changed

The Hill That Changed

Ken Gibson

Tofino, British Columbia, Canada

At the 1985 Western Regional Conference at Seaside, Oregon, I believe it was Warren Berg who explained the difference between a gardener and a collector . To borrow his expression, "a gardener looks at his garden, determines what plant would look right, goes out and buys it. A collector buys a plant, finds a spot, and plants it." By this rule, I am, unquestionably, a collector. My good fortune, however, is that my property is large enough to support my habit. (It has been known for people my age to develop worse habits.)

In 1956, my wife and I purchased an acre of land situated, at that time, on the inland edge of the developed part of the village of Tofino. (Tofino is a snug little fishing village on the west coast of Vancouver Island.) While playing cowboys as a young boy, I had discovered that this particular piece of land was actually a miniature mountain with a spectacular view of the harbour. It didn't seem to matter that the hill, covered with virgin scrub forest, was at least 400' from the main drag and on the other side of a swamp. I had already decided the view would be worth the price of two hundred and fifty dollars, plus all the work needed to clear the property.

Hard as he tried, my father, who was a very practical man, was unable to convince me to develop an easier piece of Tofino. Since the French language had driven me out of high school four years earlier, I had, instead, a few year's experience in construction, logging and blasting behind me. By late 1956, I had acquired a used 440 McCullough chain saw from the logging contractor for whom I worked and, in the short days of winter, took up the challenge of capturing the hill. This early one-man saw weighed about 85 lbs., and was one of the first in private use in this area.

After establishing boundary lines, it was necessary to start draining the four feet of entrapped water on what is now known as Fourth Street. I planted a row of ditching dynamite sticks 14" apart the length of the swamp. How the mud and grass sods flew - 150' into the air, making the surrounding trees look like a chocolate-covered wonderland. It took several rains, I might add, to wash it off.

|

|

Ditching the swamp

Photo by Ken Gibson |

The following year, a D-7 mud cat bulldozed a right-of-way to the base of the hill, I had already fallen the trees and bucked the old cedar windfalls to help expedite the "cat's" job. Fortunately, the swamp had hard-pan below the mud which allowed the machine a solid footing on which to work. The mud flowed like soup in front of the blade, refusing to be piled up, so another year had to pass before work could continue on the access road.

In the meantime, I cleared the hill top of underbrush and trees, and burned the burnable. One hemlock was fit to remain on the knoll; all the others were cat-faced cedar and poorly-formed hemlock, most of which were growing on windfall cedars - typical of our moss-covered, over-mature west coast rain forest. Many of the trees were two feet in diameter, others four feet, and were locked into rock crevices. Because of this, blasting the stumps was very difficult, and since the bulldozer with a winch could not tolerate the steepness of the hill, I decided to clear the hill by "high-lead" logging.

In exchange for back wages due me from a defunct sawmill, I acquired a donkey (two drum winch) mounted on a 24' wooden sled. I winched it through the draining swamp to the foot of the hill with mud flowing over the sled like waves over a ship's bow. I then hung the "bull block" sixty feet up in an old cedar snag, creating a spar tree. A one-man logging show was then ready to commence.

After work during the week and on weekends I was, then, married to land-clearing. Often I would get to the back end to hook a stump and discover the cable choker to be a few feet short of its mark, or that a stump would not let go. The donkey had a gear driven mainline drum so something had to give. When I felt the sled lift off the ground, I would hit the switch to stop the motor. I would, then, climb back up the hill to chop out the roots. With a ⅞" mainline as tight as a fiddle string, the stump would suddenly fly free taking most of the soil in its entangled root system to leave the rock bare. What soil that was left was soon either washed away with our annual 140" rainfall, or blown off by the summer's westerly winds.

|

|

Trees and stumps cleared off leaving bare rock

Photo by Ken Gibson |

In 1960 we concentrated on building a house. First, I constructed a 200' tramway with 4" x 4" cedar for tracks, and posts beach combed from Long Beach. A 24" flange-wheeled cart was cabled to the top of the hill with a one HP electric winch. By this method, about 30 ton of building materials were hauled up the grade to a 26' x 44' dirt-free-zone at the top. It was at this time that I learned an average house has 5 tons of gyproc. (Five tons of roofing gravel was another requirement.) Each trip up the hill took about eight minutes and carried approximately 250 lbs.

After the house became livable, I concentrated on a driveway around the hill, which took about five years to complete. A road building contractor had told me to "forget it; it's not possible for a bulldozer to get up there let alone a car". Stubborn as I was (my wife says "am") I literally chipped a circular driveway out of the hillside; blasting rock and moving it by hand to establish the grade.

|

|

"Forget it; it's not possible for a bulldozer

to get up there, let alone a car." Photo by Ken Gibson |

About this time, the first rubber-tired backhoe arrived in Tofino and I managed to get some use of it on a limited basis. One thing about the use of rock is that once it's placed, it stays placed! Having firm rock under their wheels (and a couple cases of beer) convinced some local truck drivers that this hill was a great place to dump the dirt and mud from the highway ditching projects. Mud, sods, boulders, stumps, roots, and beer and pop bottles flowed over the bank, eventually covering the blasted rock. Later, I purposely rolled the protruding larger pieces, rain washed and sun-bleached, into place at the toe of the hill. Grass, weeds and yellow broom began to grow, resulting in humidity being established, and the hill, ultimately, took a new appearance.

Any further landscaping plans were non-existent now. Besides helping raise a family, I turned to other spare time interests, including tracking down the history of the North West Coast. However, during this period of my life, I rescued a couple of rhododendrons (I now know them to be R. ponticum ) from the late George Fraser's garden in Ucluelet which was being subdivided into building lots. I planted a piece of one R. ponticum near the front door on the north side of the house and it wasn't too many years before people remarked on its appealing symmetrical shape. (Or, perhaps it was because it was the only cultivated plant on the hill!)

At this time, the only thing I knew about rhododendrons was that a couple of hundred were growing on nearby Clayoquot Island. Then, pointing to my R. ponticum one day, a close friend and avid gardener mentioned to me "what you and this hill need are rhododendrons; just look at that one! They grow well here and they don't need attention". So inspired, in 1973 I gave my cousin a twenty dollar bill and asked him if he would pick up some rhododendrons on a return trip from Nanaimo. He managed to get me ten small ones, three of which turned out to be 'Cunningham's White'. I was surprised to discover these things had names. This led me to read a Sunset book, Rhododendrons and Azaleas , and, from then on, I concentrated on names I didn't have. (Except, of course, for favorites like 'Etta Burrows', Taurus', etc.) I planted these first hardy rhododendrons in the shade of the north side of the house, protecting them from the wind by driving cedar shakes into the ground around them.

A new challenge was to get rid of a desert-like appearance on the south and west slopes of the hill. This new rhodoholic had an inspiration: COVER this hill in rhododendrons! I first planted several mature R. ponticum and 'Fastuosum Flore Pleno' on the upper side of the driveway as a wind-break. On the steeper and more barren areas, I dumped what soil I could scrape together and/or laid sods of grass from nearby ditches like a patch-work quilt. Weeds, wild parsnip and different types of grasses, mowed regularly, at least looked green and half-way respectable.

I quickly noticed that fertilizing made a tear-drop pattern of grass on the down side of each little plant, so, one summer, I watered by pumping stagnant water from our backyard creek. Believe me, septic tank effluent and dead tadpoles are great but they sure don't smell like 'Fragrantissimum' does today.

Slowly at first, and with some setbacks, the hill began to change. The humidity became regulated, companionship established, and the plants adapted to our frequent 50 MPH summer westerly winds. Though I had heard 'Unknown Warrior' couldn't be grown under windy conditions, I am proud to say that mine is flourishing very well and is quite compact. My practice is to gradually introduce my plants into our windy environment. Once established, they appear to love it. After all, rhododendrons are mountain plants.

|

|

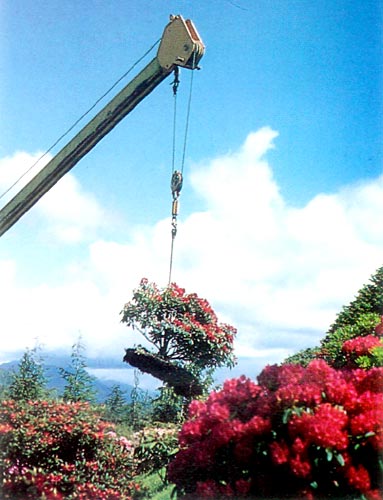

Crane at work in the garden

Photo by Ken Gibson |

|

|

Moving rhododendrons

Photo by Ken Gibson |

In hindsight, my biggest mistakes were in using too heavy a soil to retain moisture on the rocks, and planting too deeply. The sogginess promoted root rot which I didn't realize could exist on a 45 degree slope. I can now safely advise that rhododendrons should be placed, not planted. This rule also was verified by what I saw in garden culture in Washington and Oregon, a point we "wet" West-coasters must learn. I have lifted the majority of my plants by placing twenty to thirty gallons of sawdust and/or bark mulch under them. Good drainage cannot be over-emphasized and, if I were to start my garden again, I would use all bark mulch because of its aerating and moisture retention qualities. So far, I have found no evidence to substantiate the theory that cedar sawdust is detrimental to rhododendrons. However, I do know gardeners who would disagree with that statement. I probably have one of the lowest rates of failure per capita because I now know better than to drown my rhododendrons, we do not have a weevil problem, and we have a very temperate climate. My collection is now in excess of twelve hundred plants; just over six hundred names. Thanks to members from as far away as California, my collection of Maddeniis alone number over 40.

|

|

The Gibson's hillside garden

Photo by Ken Gibson |

With Tofino's average temperature of 43.5°F., I am able to grow Maddeniis outside all year round. R. cubittii and R. supranubium require a bit more protection. The temperature rarely drops lower than 20°F. We are often the warmest place in Canada during the winter, though I won't say how wet it is! Moist, warm clouds from Hawaii clear Cape Flattery and strike Tofino. On January 12 of this year, at 10:00 P.M., our temperature reached a near 70°F., but it was soon followed by five or six inches of heavy, warm, rain. The Pacific Ocean's Kuroshio or Japanese Current also keeps us warm. The mountain ridge through the centre of Vancouver Island protects us from the cold front pushing in from the Northwest. The ocean water temperature remains stable at 49°F. to 51°F., summer and winter. Coastal fog is a common summer weather condition.

The first blooms, this past season, were on 'Nobleanum Coccineum' Christmas Day. By February, it was a show piece with thirty or forty blooms. However, on Valentine's Day, many blooms were lost to a late frost as were blooms on R. moupinense and R. dauricum .

|

|

View from the hilltop

Photo by Ken Gibson |

Today, people remark about how lucky I am to have the equipment to create a flourishing rhododendron garden. I can assure you that this did not just happen. To borrow another expression, this time from Captain Robert Gray who discovered the Columbia River in May 1792 after wintering at Fort Defiance near Tofino, "determined men can do most anything". In my opinion, determination comes before education, if you are to reach your ultimate goal.

We now have visits from rhododendron enthusiasts with a variety of interests, i.e., exploration, history, hybridizing, and many more. I would say that my primary interest is identifying, promoting and propagating the many for forgotten varieties such as 'Robin Hood' and 'Karkov'. The R. strigillosum crosses of H.L. Larson are among my favorites, along with the fragrant Maddeniis.

|

|

R. taronense

Photo by Ken Gibson |

|

|

'Else Frye'

Photo by Ken Gibson |

My wife and I would like to mention, or pay compliment to, all the fine people we have had the privilege of meeting as a result of our hobby, but that would take longer than this article. We hope you will come and visit "Rhodo Heaven" and sign our guest book.

Ken Gibson's slide shows and talks at ARS meetings have introduced many members to the challenge of hillside gardening.