JARS 42n3 - An Innovative Rhododendron Garden

An Innovative Rhododendron Garden

Monty Monsees

San Pablo, California

Introduction

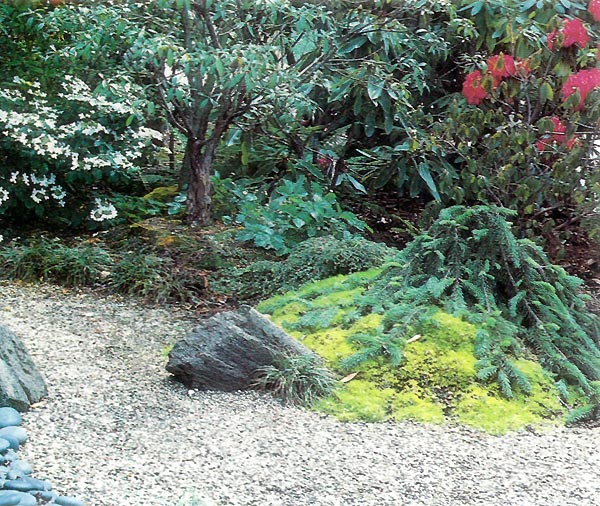

A visitor to my home will notice immediately the absence of a front lawn and see a small garden instead. A dry, gravel pond and steppingstones to the left leading through fir bark that ends at a stone water basin suggest a garden in a Japanese style. A low mound of Scotch moss and dwarf conifers adds to that impression.

If the visitor looks to the left of the entrance sidewalk, no further doubt exists in regard to a Japanese influence in garden design, for in an area of gravel rises another low mound with Scotch moss and four dwarf spruce, along with thirteen feather-rocks extending over the "island" and into the "sea" beyond. A larch bonsai, eleven inches high, its container hidden beneath the gravel, stands as part of a three-rock arrangement nearby.

From the front door, a visitor can see the Japanese garden blending into the rhododendron section and not realize that the entire garden measures only 46 feet by 42 feet. What makes this small garden seem larger, and what makes it unusual? This article details the planning and creativity involved, with practical ideas for anyone interested in growing rhododendrons in a small space, in a garden high on appeal but low on maintenance.

My garden began in a much different style, as part of a rural slope on rolling hills where wildflowers bloomed. In 1963 a developer and his bulldozers rearranged the hills into building sites, on which small houses soon grew. I began with a traditional front lawn and added a few trees and shrubs.

In 1974 I became interested in rhododendrons and began collecting them to the point that ten years later the former front lawn resembled a nursery of cluttered container-grown rhododendrons, along with a few companion plants and dwarf conifers. (Does that sound familiar?)

From that chaos evolved the current rhododendron garden after decisions on which plants to retain and which to reject. The rejects easily became choice plants in gardens of other people. Then with a plan in mind, I spent a year leisurely creating the new garden, completed in December 1985 and now into its third season.

Since I had an understanding of Japanese gardens, acquired from books and examples, and had learned about rhododendrons, I decided to combine the two kinds of gardens for something out of the ordinary. I wanted a Japanese garden in areas of sun most of the day and a forest-like rhododendron area where existing trees provide filtered shade. In design I started with the idea of an outer rim, a semicircle of rhododendrons, in front of which I visualized a series of parallel Japanese design elements, these "lines" to lead the eye into the background rhododendrons. I also kept in mind a tier effect for plant heights to recede from the entrance sidewalk to the opposite property line where the neighbor's house sits on a step above mine, the slope between the two giving my garden added visual space.

With plants in containers, I could work out an arrangement for a particular area in relationship to the overall plan, observe it over a few days, make changes until I had a satisfactory effect from various angles, and then plant that section. As in my photography, I tried to see through the eyes of an artist concerned with effective composition, for I wanted a garden interesting to view from both outside and inside the house.

|

|

Panoramic view of dry pond area; includes

R. campylogynum

var.

cremastum , Viburnum plicatum 'Fujisanensis', Iris douglasiana . Photo by Monty Monsees |

Basic Ideas Incorporated Into The Garden

I wanted maximum appeal but minimum maintenance. I wanted a garden of details, each viewing angle to reveal something not previously seen, whether from inside the house, from the entrance sidewalk, or from the two paths through the garden. I wanted year-round interest: summer for new growth and shades of green, autumn for fall color, winter for bare branches of a few deciduous trees and shrubs and for rhododendron flower buds, and spring for a bloom season extending over several months. As a result, one cannot "see" the garden on only one visit; it requires many times to observe all the details, some subtle. I consider the garden "mobile," in that it will further evolve as plants lose their visual effectiveness by growing out of scale, becoming crowded, or dying, resulting in replacement. Already I have made several changes.

|

|

Path through rhododendrons, 'Sugar Pink' upper left corner;

'Jim Drewry' upper middle; note pedestal stone lantern and how little of the street is visible. Photo by Monty Monsees |

Frame Of The Garden

A background of trees for shade existed, which I had planted years before. Although I would not consider them my first choice now, they provide filtered shade. Three weeping white birch trees planted close in a triangle shade a large expanse and remain leafless only three months. A bottlebrush trained into a tree screens late afternoon sun along the front of the house, which faces southwest. Along the street and extending in a few feet along the property line grow five myoporums trained into trees. Along that same property line two tall hop bushes help screen summer wind. A lanky Japanese black pine stands near a slender American sweet gum, and one unhappy redwood survives near the corner where street and driveway meet.

When I began the new garden, I added two Japanese maples, seedlings several years old from a tree in the rear yard, along with three evergreen dogwoods, also grown from seed but old enough to have bloomed the past two years.

|

|

Dry pond detail, 'Halfdan Lem' in bloom on right.

Photo by Monty Monsees |

Concepts From Japanese Gardening

Aside from the trees, several shrubs for accents, and numerous low-growing naturalized plants, I used only a few other plant groups, but many varieties within each. I worked with rhododendrons, dwarf conifers, and ferns, the latter an extensive collection I had acquired and continued to propagate over the years.

The tier effect of planting becomes evident whether seen from inside the house or from the entrance sidewalk. Also I arranged plants, stones, and design elements in odd numbers. In addition, straight lines exist only along the boundaries of the garden; elsewhere everything lies in some degree of curve, including the parallel design elements in the Japanese section. Even the square aggregate stepping-stones in the gravel across the front of the house form a staggered path, so that one must walk more slowly, with greater opportunity to observe garden details.

In working out plant groupings, I kept in mind leaf texture, size, shape, and shade of green. For example, on one mound of mostly blue-green conifers, a dwarf Colorado blue spruce accents the mound.

The illusion of space makes the small area (46 feet by 42 feet) seem larger. Several things work to do that: size of plants, placement of plants, and "borrowed" scenery from across the street, where a steep, green slope rises directly in front of my place. My curb trees create a screen through which one glimpses that slope but tends to overlook the patches of asphalt street. A group of tall pines at the top of the slope also adds to my view, hence the Japanese concept of "borrowed" scenery. Trees and rhododendrons obscure most of the neighbor's house where my garden slopes abruptly to the property line, again creating the illusion of space greater than exists.

Negative areas, blank (unplanted) space, I created to add visual relief, areas for the eye to rest, to add balance, and to avoid a cluttered look. Relating to unplanted space, understatement accounts for some of the visual effectiveness, such as the island in the sea of gravel along the garage wall, an area especially visible from the kitchen window and front door. Kept simple and low, the island commands attention but allows one to see over it and into the garden beyond.

Two areas suggest water where no water exists - the dry, gravel pond and the gravel sea surrounding the island. Between the two the curve of the entrance sidewalk becomes a bridge.

Innovations

Who can create a garden without problems? In my location the soil, not good for rhododendrons in the first place, has poor drainage; and we know that rhododendrons require adequate drainage. Consequently, rhododendrons sit on top of the ground, with appropriate soil (my own rhododendron mix) mounded around the root system. To anchor a plant, especially larger ones, I drove three or four square redwood stakes against the sides of the root ball slightly below the top, making the stakes invisible but holding the plant in place. Not wanting a garden of monotonous plant humps, I added more soil between some humps to form a low ridge or filled in to create a mound or low plateau. Around some humps I planted alpine strawberries (non-runner variety), and where seedlings come up and I don't want them in a particular spot, I pull them out; however, I usually let strawberries naturalize and pull out two-year-old clumps no longer attractive. I also use ferns the same way that I use strawberries.

|

|

Stepping stone path across front of house, various dwarf

rhododendrons on each side and in background. Photo by Monty Monsees |

Ways Of Tying Together Individual Areas

Many varieties and duplications of dwarf spruce tie together various parts of the Japanese section. For its yellow-green color as contrast to the greens of spruce, Scotch moss carpets three mounds of dwarf conifers. The same kind of gravel forms the dry pond, the "sea" around the "island," and the steppingstone path across the front of the house. I used the same kind of stones throughout the Japanese garden. I chose featherock (coarse pumice) for two reasons: I already had some that had moss on them, and I could select new pieces for size and shape and easily carry them.

|

|

Low stone lantern (Yukimigata) and surrounding

plants including unnamed hybrid rhododendrons. Photo by Monty Monsees |

Japanese Objects As Accents

I also needed additional ways to tie the Japanese section to the rhododendron area. Along with planting a flowering Japanese cherry tree among the rhododendrons, I placed a pedestal stone lantern (tachigata) near the cherry tree.

Where the steppingstone gravel path across the front of the house divides to form a path without gravel through the rhododendrons, a low stone lantern stands (yukimigata), snow-viewing design.

Under a Japanese maple, near rhododendrons, and at the end of the steppingstones across the fir-bark area sits a stone water basin (tsukubai), lotus blossom design. It has a traditional arrangement with bamboo spout, kneeling stone, a low rock on the right, a taller one on the left, and a sea of black pebbles into which the overflow spills. From the bamboo spout a plastic garden hose runs underground to a faucet at the rear of the house; when I want the sound of trickling water in the garden, I turn on the faucet slightly.

Another sound occasionally occurs in the garden, this one from a triangular-sided, three-toned, rusted steel wind bell hanging in the bottlebrush. Not in breezes but only during wind does it sound its tones, like distant temple bells.

|

|

Japanese stone water basin.

Photo by Monty Monsees |

Garden Maintenance

I modified the lawn sprinkler system by converting to only enough gray plastic risers to water the garden with a misty spray. Since I have no mildew problem, I program the system to water various areas for different durations at night, leaving moisture on the plants until morning.

To eliminate weeds, sheets of black plastic with slits for drainage lie beneath bark and gravel. Since I mulch with pine needles under rhododendrons, I have few weeds among them. Otherwise, I apply Roundup or pull out the weeds.

Last year I did no spraying; this year I might. Applying fertilizer to plants once each year (February or March), deadheading rhododendrons, and occasionally grooming some areas help reduce garden maintenance to the minimum I had in mind.

Additional Information

Including a complete plant list with this article seems superfluous, but some general plant information does seem appropriate. For example, 60 rhododendrons (24 species, 36 hybrids, many dwarf forms), 36 varieties of ferns (many dwarfs and duplicates), and 19 varieties of dwarf conifers (much duplication) make up the three main plant groups. Add 24 varieties of low-growing plants naturalized throughout the garden and 4 camellias. The low companion plants include alpine strawberry, columbine, cyclamen, iris (low Pacific Coast native), mondo grass, redwood sorrel, terrestrial orchid, trillium, and violet. Were I to do the same garden elsewhere, I would select rhododendrons and other plants that grow well there.

Garden Humor

It seems appropriate to include some humor on "problems" for which I did not plan. I find it amazing how many people think they can walk on water. For instance, consider the dry pond. Clearly it suggests water, yet people frequently walk out over it to look more closely at something on the other side. Perhaps they do not realize that in a Japanese garden gravel areas are not for walking on unless stepping stones lead the way or a gravel pathway is clearly evident. Water-walking visitors do not know that after they leave their footprints on the gravel I have to rake it to suggest water again.

I had a similar problem with an overweight mailman, who indirectly improved a part of my garden by causing me to relocate a rock arrangement. He assumed the gravel "sea" surrounding the "island" existed to be walked on, as a shortcut to the mailbox by the front door. I did not want to waste time waiting around to see him in order to ask him to use the sidewalk, and I did not want to write a letter to the mailman, either of which would have saved me considerable time and effort.

Instead, I assumed that my putting up a temporary row of low stakes would prevent the mailman from cutting across the gravel. He stepped over the stakes. I replaced them with higher ones. He stepped higher. I added string. He added a longer stride. I moved the larch bonsai and three rocks to a new location, to block his path. He moved his shortcut to the other side. (I liked the bonsai in the new location and considered it an improvement and left it there.) I added three signs on tall stakes, signs explaining that the gravel was for looking at, not for walking on. He stepped between them.

Finally, one day I saw the mailman backtrack to read one of the signs. The next day he waddled up the entrance sidewalk. I took down the signs, the string, the stakes. Yet, people unaware of the aesthetics of a Japanese garden often continue to walk on water.

Photography Of The Garden

The photographs accompanying this article show limited views of my garden but perhaps enough to indicate that I gained the best of two worlds in a seemingly impossible small space - an innovative combination of a rhododendron garden and a Japanese garden. I never tire of looking into the garden or wandering through it, and always I, too, see some new detail.