JARS v45n3 - Germination of Rhododendron yakushimanum Seed

Germination of Rhododendron yakushimanum Seed

Russell Gilkey

Kingsport, Tennessee

When I first joined the American Rhododendron Society in 1969, it was for the purpose of learning more about what rhododendrons to buy and where to buy them. They were to be used in landscaping my new home. One thing led to another and it eventually mushroomed into a time consuming but enjoyable hobby. As Zorba the Greek said about marriage: a wife, a house, a family, the whole catastrophe. Mine is collecting and growing rhododendrons and azaleas, rooting cuttings, making crosses, growing seedlings and experimenting.

In 1973 my second order of rhododendron seeds arrived from the ARS Seed Exchange. Included in this batch were four different seed lots of Rhododendron yakushimanum (herein after to be called "yak"). From them 6, 20, 4 and 2 seedlings were obtained. Almost every year since then, one or two yak seed lots were ordered. In 1982 an outstanding 84 seedlings were obtained from one seed lot. Otherwise, the average over the years, for 13 different seed lots, was 13 seedlings with a high of 38 and a low of 3. Other species rhododendron and hybrid crosses gave much better germination so my method of growing seedlings wasn't to blame.

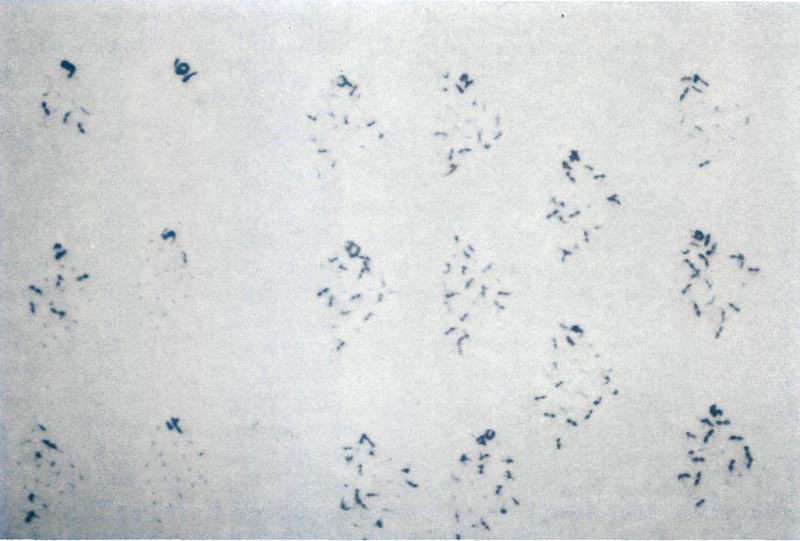

I should have been happy with the number of yaks I got. However, all germinated seedlings don't make it to maturity, and when you give most of them away you need more to give away. Then too, the plant appeals to me from the time it develops its first set of leaves until it grows to blooming size. A typical batch of young seedlings is shown in Figure 1. They are attractive plants and I like to watch them grow. There is no problem in giving them away. But in the final analysis, the real motivating force to find a way to get better germination is the challenge.

|

|

Figure 1: A typical batch of

R. yakushimanum

seedlings

Photo by Russell Gilkey |

In 1983 one of my seedlings (ARS Seed Exchange 75-330, the Exbury form, crossed with the F.C.C.' form by Mrs. H. Baird of Bellevue, WA) and my F.C.C. form (from a nursery in Seattle) both bloomed and were crossed to give plenty of seed for experimentation. This seed, designated 83-11G, was harvested in October and appeared to be perfectly normal. However, in several trials, germination ranged from only 2 to 11 percent. No improvement in germination was obtained when the germinating medium was wet with varying amounts of water or the seed soaked in water for 1 to 16 days before sowing. Stratification, freezing, warm and cold cycles were only marginally successful.

Before I retired in 1979, part of my lunch hour was spent in going through Chemical Abstracts and looking up references relating to rhododendrons. In reviewing these references, I found two that dealt with germination of seeds. According to Olavi Junttila ( Chem. Abstracts 77 176(1778m)1972) gibberellic acid stimulated the light and dark germination of Calluna vulgaris , Ledum palustre and Rhododendron lapponicum seeds, and at 0.2-3.2 mM (66-1062ppm) concentrations gave about 100% germination. Untreated rhododendron seeds were completely dormant in light at 13-24°C. According to K. Prasad et al. ( Chem. Abstracts 86 111(26839f)1977) seed dormancy of Cretalaria juncea (a tropical plant, not a rhododendron) was broken by gibberellic acid (100ppm), thiourea (2%) and boric acid (50ppm). This did not constitute a complete literature search nor have I subsequently attempted to conduct a search. However, it was enough to get me started on the path that eventually led to success.

A spray can of Wonder-Brel, which contained 50 ppm gibberellic acid (potassium salt) and boric acid were available. Water solutions containing approximately 25ppm of each were prepared and yak seed 83-11G was soaked in each at 65°F for 24 hours. The treated seeds were sowed and 0% germination was obtained with the gibberellic acid and 50% with the boric acid treatment compared to 5% for the control.

Eureka! I thought I had found a successful treatment. In retrospect, I can explain the result with gibberellic acid, but to this day I still don't know why that particular boric acid treatment worked. A lot of time and effort was spent over the next couple of years on yak seeds from various sources trying to duplicate that experiment. Many variations were tried and concentrations of boric acid from 15-240 were used. The final conclusion was that boric acid was not the magic ingredient, at least not for yak seed.

In one experiment with a boric acid concentration series, yak seed 83-11G which hadn't germinated was sprayed with Wonder-Brel. Later it was sprayed with an aqueous solution containing 10ppm of indole butyric acid. Also during the course of the experiment, the seed bed was refrigerated for 30 days. After all these treatments, the control (no boric acid) had 32% germination which was higher than the germination of those in the series which had initially been treated with boric acid. Was this apparent increase in germination due to gibberellic acid, indole butyric acid, stratification or a combination of several factors? Later when I finally gave up on boric acid, I looked back at the results of this experiment and decided to investigate gibberellic acid again.

In 1987 my Exbury form of yak bloomed and seed was obtained from a cross of yak, F.C.C. X yak, Exbury (87-31G). Another source of gibberellic acid was found. It was a bottle of Wonder-Brel my daughter had used in a school science project years before. It contained 175ppm gibberellins. It was about this time that I decided experiments were using up too much milled sphagnum so a germination test procedure on filter paper was instituted. This procedure was carried out in the following manner.

Seeds, whether from the ARS Seed Exchange or my crosses, were stored over Drierite in containers in the refrigerator until needed. A typical germination test involved counting out 25-30 seeds of each rhododendron variety. Each batch of seeds was immersed in 10 ml of 9/1-water/Clorox for 15 min. (1989 development); poured onto a piece of paper toweling in the shape of a funnel; washed four times with water and removed from the toweling with a knife blade. The Clorox pretreated seeds were either immersed in about 4 ml of water (control) or a water solution of gibberellic acid for a prescribed period, usually 24 hours. The contents were then poured onto a piece of paper toweling as above but not washed with water. Some of the effectiveness of gibberellic acid, at lower concentrations, is lost if the seed is washed with water at this stage. The bottom of a plastic storage box with a clear plastic lid was fitted with a white terry cloth towel and numbered (Sharpie pen); pieces of coffee filter paper were placed on the thoroughly water-wetted towel. Twenty each of the 24 hr.-soaked seed were distributed over one piece each of filter paper in the storage box. The box lid was put on and the box was placed about 5 inches below 40W fluorescent shop lights timed for 16 hrs. of light per day. Room temperature ranged from 70-76°F (winter to summer).

A similar procedure was carried out when seedlings for transplanting were wanted. The treated seed was sown on top of a mixture of 2/1-milled sphagnum/vermiculite contained in a clear plastic shoe box with a clear plastic lid. The shoe box was usually divided into several compartments with plastic dividers to accommodate several seed lots. The medium was wetted with water before placing in the shoe box. It was lightly pressed with a wooden block to get a fairly smooth surface.

Using the Wonder-Brel containing 175ppm gibberellins, aqueous solutions containing 5, 20, 80 and 160ppm gibberellins were prepared and yak seed 87-31G was soaked in each solution for 24 hrs. Twenty-one days after the seeds were placed on filter paper, germination was 30 and 80%, respectively, for 5 and 20ppm; 0% for 80 and 160ppm and 30% for the control soaked in water. There was a glimmer of light at the end of the tunnel. The question was whether it was another red herring, and if not, what were the concentration limits. The fact that 80 and 160ppm didn't work was suspect since there was a strong odor of an organic solvent in the Wonder-Brel. This prompted the search for a more concentrated solution of gibberellic acid. One was found at the McDonald's Lawn and Garden Center in Hampton, VA during the 1988 National ARS Convention. The product, Camellia Gibb, contained 15,000ppm gibberellic acid. Germination experiments on filter paper with this material and with indole butyric acid singly and in combination gave the following results. Aqueous solutions containing 20 and 80ppm indole butyric acid (a rooting hormone) increased germination from 30 to 60%, but 160ppm had an adverse effect. Gibberellic acid in concentrations of 20, 40, 80, 160, 320 and 640ppm increased germination to the 70-95% range. These experiments suggest that the organic solvent in the Wonder-Brel was responsible for the failure of gibberellic acid to work in the initial experiment with Wonder-Brel from the spray can; also the negative results with 80 and 160ppm when Wonder-Brel from the bottle containing 175ppm was used. Using various combinations of gibberellic acid and indole butyric acid offered no advantage over using gibberellic acid alone. Some combinations were less effective so the use of indole butyric acid was abandoned.

Many experiments were carried out with the Camellia Gibb over a period of two years. In addition to gibberellic acid concentration, the effect of time of soaking was also investigated. A series of soaking times was run with 0, 100 and 400ppm gibberellic acid using filter paper as the germinating medium. A yak, F.C.C. X yak, Exbury cross, 89-48G, harvested in 1989 was used. Without treatment, this cross consistently gave poor germination, 15% or less. Table 1 shows the results of this experiment.

| Table1: % Germination of Yak Seed vs. Soaking Time in and Concentration of Gibberellic Acid | |||

|

Germination of yak Seed 89-48GF

on Paper in 33 Days |

|||

|

Soaking Time in

Gibberellic Acid Solutions |

Gibberellic Acid Concentration | ||

| 0 ppm | 100 ppm | 400 ppm | |

| 6 hrs. | 15 | 50 | 85 |

| 12 hrs. | 0 | 50 | 70 |

| 1 day | 10 | 75 | 95 |

| 1 day | 5 | 65 | 90 |

| 1 day | 5 | 75 | 100 |

| 1 day | 10 | 70 | 85 |

| 2 days | 0 | 85 | 90 |

| 4 days | 0 | 65 | 85 |

| 8 days | 0 | 60 | 80 |

Reproducibility is pretty good considering that only 20 seed, selected at random, is used per individual test. A soaking time of one day turned out to be satisfactory which was fortuitous since that is what had been used in previous experiments. The one day soaking was standardized for subsequent experiments.

One concern of mine after years of germinating rhododendron seed was the presence of mold spores which would develop on some seeds before they had a chance to germinate. Would a fungicide help and would it interfere with the gibberellic acid treatment? To answer this questions yak seed was given a pretreatment by immersing them in a 9/1-water/Clorox solution, or a suspension of ½ teaspoon Benlate in 40 oz. water, prior to the 24 hr. gibberellic acid soak. Yak seeds 87-31G and 89-48G were used (20 seed each test). Germination versus time was followed. Also included in the experiment was the effect of longer pretreatment with Clorox and higher concentrations of gibberellic acid. The results are shown in Table 2. A photograph, at the end of the experiment in Table 2, is shown in Figure 2. The sample number in Table 2 corresponds to the number on the filter paper in Figure 2. It is easy to see that samples 4, 5 and 6, without gibberellic acid, didn't germinate but the corresponding 10, 11 and 12, with gibberellic acid, germinated very well. The measure of germination used in all experiments was extension of the radicle to at least 3 mm. Most, but not all, would then develop cotyledons, and if the filter paper were kept moist, roots and true leaves would develop. However, I don't recommend this as a method to grow seedlings. Some I transplanted from filter paper didn't do too well.

|

|

Figure 2. Photo was taken after the experiment shown in Table 2.

The numbers correspond to the samples in the Table. Numbers 4, 5 and 6 were not treated with gibberellic acid, but 10, 11 and 12 were treated. Photo by Russell Gilkey |

| Table 2: Germination vs. Time and Gibberellic Acid Concentrate of Yak Seed Presoaked in Fungicide and Soaked in Gibberellic Acid Solution | ||||||||

| Sample No. | Yak Seed | 20 Min. Pretreatment With | Gibberellic Acid Concn. | % Germinated on Paper After | ||||

| 10 days | 15 days | 20 days | 30 days | 40 days | ||||

| 1 | 87-31G | Water | 0 ppm | 0 | 20 | 30 | 35 | 40 |

| 2 | 87-31G | Benlate | 0 ppm | 0 | 20 | 20 | 25 | 25 |

| 3 | 87-31G | Clorox | 0 ppm | 0 | 35 | 45 | 50 | 55 |

| 4 | 89-48G | Water | 0 ppm | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 89-48G | Benlate | 0 ppm | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| 6 | 89-48G | Clorox | 0 ppm | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 7 | 87-31G | Water | 400 ppm | 0 | 60 | 70 | 75 | 75 |

| 8 | 87-31G | Benlate | 400 ppm | 0 | 45 | 70 | 75 | 75 |

| 9 | 87-31G | Clorox | 400 ppm | 25 | 70 | 70 | 80 | 80 |

| 10 | 89-48G | Water | 400 ppm | 0 | 45 | 55 | 75 | 75 |

| 11 | 89-48G | Benlate | 400 ppm | 5 | 45 | 65 | 75 | 75 |

| 12 | 89-48G | Clorox | 400 ppm | 5 | 70 | 85 | 100 | 100 |

| 13 | 89-48G | Clorox | 800 ppm | 15 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 75 |

| 14 | 89-48G | Clorox | 1600 ppm | 15 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 80 |

| 15 | 89-48G | Clorox | 3200 ppm | 0 | 20 | 40 | 45 | 50 |

| 16 | 89-48G |

Clorox

(40 min) |

400 ppm | 0 | 90 | 90 | 95 | 95 |

| 17 | 89-48G |

Clorox

(60 min) |

400 ppm | 10 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Germination in this experiment was not adversely affected by the fungicide pretreatment. On the contrary, it seemed to be enhanced by the Clorox pretreatment. This was verified in later experiments. Since these seeds were already fairly clean, no judgment could be made concerning the effect of fungicides on producing a cleaner seed. However, later experiments with a variety of seeds, using a pretreatment with Clorox, have demonstrated that a cleaner batch of seed can result with no deleterious effect. This doesn't mean no mold, just less mold developing on the seeds. Increasing the pretreatment time from 20 to 60 minutes didn't hurt germination but did bleach the seed practically white. In later experiments with a variety of seeds, a 15 minute 9/1-water/Clorox pretreatment was used as a standard. The effect of a longer pretreatment on a variety of seeds is not known, but 15 minutes was long enough to bleach some seed varieties white.

Yak seed 87-31G was included in the experiment to see if it was still viable after storing in the refrigerator for two years. It was. The concentration series of gibberellic acid indicates that an upper limit to effectiveness may be approaching above 3000ppm. Gibberellic acid treatment makes the seed start germinating earlier and finish germinating sooner.

The germination percentage of yak seed from various sources, ARS Seed Exchange and my crosses, has been recorded since 1985. The percentage germination, average/high/low, for 18 different batches was 12/55/0. Nine of my crosses had 10/55/0 without gibberellic acid treatment and 60/95/20 with. Why they vary so much is a mystery. For example, a cross between the same plants, yak, F.C.C. X yak, Exbury, made in 1988 and 1990 gave 85/5 and 20/0% germination with/without gibberellic acid treatment. There was no obvious difference between the seed pods or the seeds.

Another observation is that treatment with a higher concentration of gibberellic acid is required on milled sphagnum than on filter paper. For example, to get the same degree of germination with 400ppm gibberellic acid using filter paper, 1600ppm is required using milled sphagnum. My guess is that the sphagnum contains a germination inhibitor of some kind. Whatever the cause, it is not affected by treatment of the sphagnum with boiling water. My Mosser Lee milled sphagnum is loaded with a mold spore of some kind. Thread mold develops with a vengeance before the rhododendron seed starts germinating. To combat this problem, (1) the mold is sprayed several times at intervals with Benlate after it starts developing or (2) the milled sphagnum is pretreated by heating it with stirring in gently boiling water for 30 minutes in a canning kettle. The second alternative has been used for the last couple of years. Not only is the thread mold discouraged but also growths of other undesirables.

| Table 3: % Germination of a Variety of Rhododendron Seed with and without a Fungicide Pretreatment and Subsequently Soaked in Gibberellic Acid Solution | |||||

|

30 Seed Germinated on 2/1-Sphagnum/

Vermiculite |

|||||

| 20 Seed Germinated on Filter Paper | |||||

| Seed Description |

No

Treatment |

Clorox Pretreatment 24 hr.

Water Soak |

No Pretreatment 400ppm Gibberellic Acid Soak | Clorox Pretreatment 400ppm Gibberellic Acid Soak | Clorox Pretreatment 800ppm Gibberellic Acid Soak |

| 'Antoon van Welie' x yak | 59 | 40 | 30 | 45 | 43 |

| yak X R.. degronianum 82-623 | 40 | 60 | 60 | 100 | 50 |

| yak, F.C.C. X yak 85-612 | 9 | 0 | 45 | 65 | — |

| 'Mrs. Tom H. Lowinsky' X yak | 33 | 25 | 65 | 95 | 87 |

| (yak X 'Sphinx') X (yak X 'Sphinx') | 10 | 35 | 65 | 85 | 63 |

| 'Mars' X yak X yak X 'Sphinx' | 28 | 60 | 75 | 95 | 77 |

| R. fortunei X yak | 65 | 55 | 65 | 90 | 77 |

| 'Chionoides' X yak | 8 | 40 | 40 | 80 | 50 |

| 'Robert Allison' X yak | 69 | 75 | 85 | 95 | 83 |

| 'Lord Roberts' X yak | 42 | 50 | 70 | 65 | 67 |

| 'Damozel' X yak | 60 | 75 | 75 | 60 | 67 |

| yak, Exbury X yak, F.C.C. | 0 | 0 | 55 | 80 | — |

Gibberellic acid does wonders in promoting germination of yak seed. How about other rhododendron and azalea seeds? A typical experiment to answer this question is shown in Table 3. These were my 1989 crosses. The filter paper experiment was performed in March, 1990, on 20 seed of each variety. A 24 hr. soak in water, without Clorox pre-treatment, was not run in this experiment because previous experience had shown that a water soak has a negligible effect on seed germination. It was September, 1990, before the experiment on 2/1-milled sphagnum/vermiculite with 30 seed each could be run because my supply of gibberellic acid had temporarily run out. Actually, this part of the experiment was made in order to obtain seedlings. The seedlings have been transplanted and are growing nicely. Treating seeds with gibberellic acid has not affected the growth and development of seedlings. The two yak crosses were not germinated to get seedlings since I already had more than enough yak seedlings from previous runs. It is obvious from Table 3 that a gibberellic acid treatment of most seeds is a waste of time. It isn't necessary in order to get all the seedlings you want.

A comparison of gibberellic acid treatment versus untreated controls has been run on 50 seed lots in the last two years. Some were my crosses, some were from the ARS Seed Exchange and some were from the Rhododendron Species Foundation. Included were species rhododendron and azaleas, and various crosses. After eliminating those that didn't germinate by either method, and the yak seeds, there were 36 seed lots. An overall average for the 36 seed lots treated with gibberellic acid was 54% germination after 30 days; for the control, 41%. There does seem to be a positive effect, but not worth the effort for seed that germinates at all reasonably. So far, other than yak, the following seeds have needed a gibberellic acid treatment to get a reasonable number of seedlings: yak, F.C.C. X R. traillianum , yak, F.C.C. X R. calophytum , yak, F.C.C. X R. maximum and R. albrechtii .

Another characteristic of gibberellic acid treated seed is that they start and finish germinating sooner. They start in 7-9 days and are finished in 3 weeks. Untreated seeds generally start in 12-14 days and finish in 4 weeks, except for a few stragglers with some seed varieties.

My supply of gibberellic acid from Camellia Gibb ran out before experiments in 1990 were completed. An inquiry to the manufacturer disclosed that Camellia Gibb was no longer available. It was suggested that I contact Abbott Laboratories about their product, Pro-Gibb. A very accommodating person in the Chemical and Agricultural Products Division at Abbott Laboratories sent me literature about Pro-Gibb and a one gram experimental sample of gibberellic acid. That was enough to complete the planned experiments and an ample supply for any future experiments. Pro-Gibb is registered for use on a variety of fruit and vegetable crops. It is not registered for use on rhododendron seed, but that does not preclude its use for experimental purposes. Many agricultural chemical companies that work with fruit crops carry Pro-Gibb. However, two products, Pro-Gibb Plus 2X Soluble Powder and Pro-Gibb 4% Liquid Concentrate, being agricultural chemicals, contain enough gibberellic acid (32g or more per bottle) to supply a great many experimentalists for life. Experimental quantities may be available from suppliers of fine chemicals.

The main conclusion to be drawn from these experiments is that a 24-hr, soak of R. yakushimanum seed in a water solution containing 800-1600ppm of gibberellic acid dramatically increases the germination of the seed. Several seed varieties of rhododendron and azalea, other than R. yakushimanum , have also greatly benefited from the treatment. Most rhododendron and azalea seed germinate satisfactorily without such a treatment.

Editor's note: F.C.C. stands for First Class Certificate, a species award given by the Royal Horticultural Society.

Russell Gilkey is a retired research chemist from Tennessee Eastman Company. He received his Ph.D. in organic chemistry from the University of Illinois. As a hobby he raises, propagates and hybridizes rhododendrons. He is an active member of the Southeastern Chapter of the ARS and is a member of the ARS Research Committee.