JARS v45n3 - Rhododendron chapmanii: An American Survivor

Rhododendron chapmanii: An American Survivor

Charles S. Hunter

Marietta, Georgia

It seems somewhat ironic that rhododendron enthusiasts in the Pacific Northwest seem to be able to grow just about any hybrid or exotic Asian species, yet this same environment is the native home to only one evergreen rhododendron and a single native azalea species. On the other hand, we in the Southeast find several different evergreen rhododendrons in the wild, along with some 14 native azalea species, but we are more restricted in the rhododendrons that do well here, due in large part to our extremes of temperature and irregularly dry summer periods. In the Atlanta area where I live, when experimenting with new plants, I am much more likely to lose one to the summer climate than to the winter cold, even though this area is in the Upper Piedmont at about 1,000 feet elevation, just south of the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains.

It would appear to defy logic even more that an evergreen rhododendron would grow in the gray sand of the blazing hot coastal plain of northern Florida, but Rhododendron chapmanii is found in the wild no further north. I have visited the three known populations of this rare and fascinating plant within the last 12 months.

Most Isolated Population

By far the smallest and most geographically isolated of these locations is within the Florida National Guard post at Camp Blanding in the northeastern part of the state. This area is also included in a larger federally protected Wildlife Management Area. I attended a seminar near Jacksonville last November and was able to make a small diversion on my way home to inspect the habitat. The plants grow between two old roads in a wooded area of less than one acre near abandoned World War II military housing. The extensive grading and construction at Camp Blanding in the 1940s killed most of the rhododendron population, and these survivors actually re-sprouted from an area which had been bulldozed and graded with no regard to the plants at all.

While I was inspecting the area, a burly MP pulled his jeep behind my car and asked me what I was doing there. Seeing that I had a camera rather than a shovel, he become friendly and proudly revealed that he had been the discoverer of these plants when he had noticed them in bloom only a couple of years before! I certainly had no inclination to burst his bubble, and I could not imagine that the rhododendrons could have a better protector than this gentleman, so I declined to take issue with him about his "discovery". The federal Wildlife Management Area people are also very aware of the rhododendrons, so suffice it to say that the people at Camp Blanding know about these plants and don't much want folks messin' with 'em!

|

|

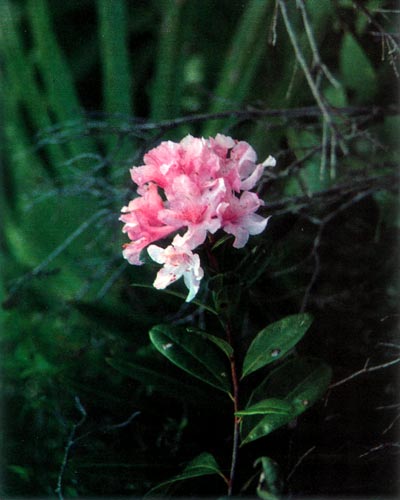

R. chapmanii

near Tallahassee, Florida

Photo by Charles S. Hunter |

Largest Population

The largest population is located in the middle panhandle within 75 miles of Tallahassee. This habitat of less than 10 square miles is certainly not solid with the plants, but consists of a few large to medium groups, along with some small groups and even individual isolated plants, all widely scattered through the area. This land is privately owned and used for tree farming, as is much of the land in the Florida panhandle.

The rhododendrons often grow between the planted rows of pine trees, generally near natural creeks and wet areas. When the pine trees have been harvested and the underbrush cut, these rare rhododendrons also have been leveled indiscriminately to the ground. As appalling as this may sound, this is by no means harmful to the plants, as they defiantly sprout up from the remaining roots to grow again with the new pines. This actually duplicates the natural fire process that the rhododendrons are adapted to and encourages bloom and resulting seed by eliminating excess shade on the plants. Only when the land is ploughed up with bulldozers and root rakes are the rhododendrons killed, and the landowners are not using this method for tree site preparation in the areas where they are made aware of the existence of the plants.

|

|

R. chapmanii

near Tallahassee, Florida

Photo by Charles S. Hunter |

My friend Steve Yeates and I visited the Tallahassee habitat on March 30th of this year (peak blooming time). We saw a huge totally leveled area along one side of a logging road, but were pleased and surprised to see that new wooden posts had been sunk into the ground around a sizeable group of Rhododendron chapmanii growing on the west side of a tiny branch. I later learned that this small branch, at this location and downstream, supports the largest known concentration of Chapman's rhododendron in the wild and that the landowners had voluntarily placed the posts at the urging of conservationists. This represents the first ever such protected area for these plants. Time will tell whether restricting the tree cutting in the small area next to this branch will cause overgrowth deterring procreation of the plants, but what I saw was a concentration of large rhododendron plants with an unrestricted western exposure of Florida sun, resulting in a spectacular display of pink blooms next to an otherwise bleak and denuded land area waiting to be planted with new pine seedlings.

Rhododendron canescens and R. serrulatum also grow in the same area, but oddly are never seen growing in the exact location where the R. chapmanii grow. R. austrinum , the least common azalea native to Florida, does not grow near R. chapmanii .

|

|

R. chapmanii

, Gulf County, Florida

Photo by Charles S. Hunter |

Most Threatened Population

The third known location is in Gulf County, Florida, and is again primarily on tree farming land and in even more widely scattered groups. These plants are found generally within a few miles of the Gulf Coast along sand ridges near wet situations, and some are close to populated areas. My sources in Florida stated that they had not visited the Gulf County habitat in a number of years and were unsure of the state of those plants. Despite the tiny population at Camp Blanding, my personal opinion is that the greatest risk of permanent loss of Chapman's rhododendron habitat is in Gulf County.

Time constraints (I had one day) prohibited me from exploring the Gulf County area nearby as thoroughly as I would have liked, but I found relatively few plants, and the ones I found were relatively small and inferior to the Tallahassee rhododendrons. I suspect this is because of the poor soil environment. Also, probably some plants were re-sprouted, having been recently cut to the ground with the pine trees. I was disappointed to see one of the reported areas knee high in weeds, having been recently harvested of its trees. If the rhododendrons were there (and I suspect they were), they were under the weeds. Nearby, the pines were 10 or 15 years old, and a few smallish Rhododendron chapmanii were blooming in between them along with a lot of palmettos. I am sure there are more plants down there than what I saw, and it would have been nice to have had more time.

|

|

R. chapmanii

, Gulf County, Florida

Photo by Charles S. Hunter |

There are undoubtedly other small populations that are undiscovered or only locally known, and there are unconfirmed reports of other panhandle locations. Some previously known wild stands have been eliminated because of development or excavation. Fortunately, none of the known present populations are in areas that appear to be attracting the attention of developers, but if the tourist trade and extensive development of the Panama City area ever rubs off on neighboring Gulf County, the rhododendrons could be in big trouble. Unless there is an immediate or serious threat to their habitat, any public outcry or popular movement towards legislative protection risks carrying with it unnecessary publicity which can draw too much attention to the plants. In Gulf County, the plants have been taken for granted or gone unnoticed for years by the locals, and if everyone in the county knew what they were and that they were scarce, it is a safe bet that at least some plants would be dug from the wild. Perhaps nature conservancy organizations could quietly purchase some small habitat tracts in the future.

Species Controversy

There is a difference of opinion as to whether

Rhododendron chapmanii

and its relatives,

R. carolinianum

and

R. minus

, are separate species or merely varieties of

R. minus

, and there exists some confusion and misinformation about differentiating between them. I will leave the species versus variety debate to the botanists, but from observing both wild and garden plants, I believe that the easiest and most reliable single method of identification is by bloom time.

R. chapmanii

is the earliest, blooming for a two-week period around April 1st.

R. carolinianum

, a mountain plant, begins its bloom as the pink blooms of the Chapman's rhododendron are almost spent.

R. minus

, the most widespread and common of the three in the wild, blooms last, and there is no overlap at all with the flowering of

R. chapmanii

and probably no natural hybrids between the two, as R.

minus

is not known to exist in Florida.

Other differences also exists. Chapman's rhododendron, unlike the other two, is not used to cold weather and does not know to turn its foliage bronzy red in winter temperatures. Rhododendron carolinianum is a bushy and compact shrub, while the other two are noticeably more leggy.

In his exhaustive work on rhododendron species 1 , Davidian makes the distinction that the two northern species have small hairs on the midrib of the upper leaves, unlike the hairless midribs on Rhododendron chapmanii . I find that this does not hold true for the plants of R. minus found in the south Georgia coastal plain along the Chattahoochee River corridor. They may also lack the hairs. The "typical" R. chapmanii light green, rounded, re-curved and bumpy leaf is consistent in the Camp Blanding population, but is more variable in the panhandle plants.

Particular About Habitat

According to J. Patrick Tatum's excellent article in the Spring 1984

Journal ARS

, relating to the habitat of

R. chapmanii

, they are very particular about the constant water table of their habitat and grow only "on sands with abundant organic matter that are well drained at the surface, permanently saturated with soft, acid water just below the surface, and yet never subject to flooding." I have never observed them growing very far from water, and this may partially explain their heat tolerance. It strikes me as ironic that a plant which is that particular about its native habitat survives these seemingly hostile activities of man and is easily grown in non-sandy soil much further north than its native Florida. The species is available from the Rhododendron Species Foundation and numerous specialty nurseries. I believe that the known populations are stable at present, with no significant increase or decrease in numbers of plants in recent years.

While a tough survivor, Rhododendron chapmanii is definitely an endangered species, and is probably the scarcest wild rhododendron in North America. Every member of this Society should be aware of the importance to maintain the native populations of these rare plants.

Charles Hunter is a trial lawyer in the Atlanta area and a member of the Azalea Chapter of the ARS and the Rhododendron Species Foundation. He has a special interest in the eastern native azalea and rhododendron species and has traveled extensively within Georgia and adjacent states to photograph and observe them in the wild.

References

1. Davidian, H. H. The

Rhododendron Species, Volume I, Lepidotes

, Timber Press, 1982.

2. Tatum, J. Patrick. "The Native Habitat of Chapman's Rhododendron," Journal ARS , Vol. 38, No. 2, Spring 1984.