JARS v45n3 - Archibald Menzies & the Discovery of Rhododendron macrophyllum: Part 1

Archibald Menzies & the Discovery of Rhododendron macrophyllum: Part 1

Clive Justice

Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

The first official collection of Rhododendron macrophyllum by white explorers in the Pacific Northwest was made by Archibald Menzies, a botanist sailing with Captain George Vancouver, in the summer of 1792. While Vancouver was negotiating with the Spanish to leave the area so that the British could defend their seal and otter trade from the Russians, Menzies was ashore collecting specimens for King George's garden at Kew.

This fascinating story of Menzies and the native Pacific rhododendron was first told by Clive Justice at the ARS Western Regional Conference at Whistler Mountain, British Columbia, in October 1990.

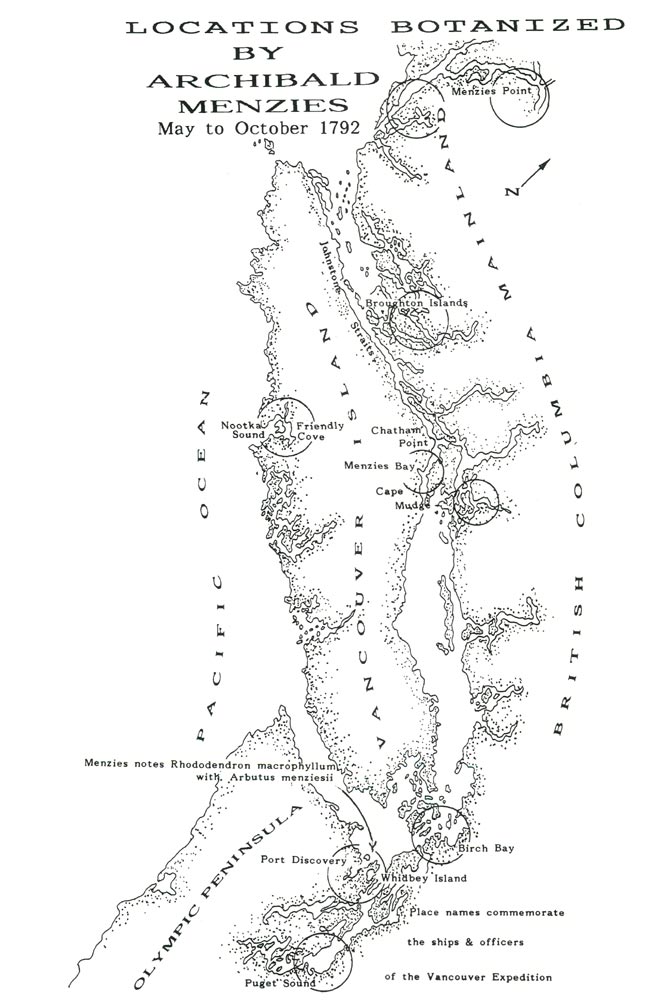

The story I wish to relate here is the story of Captain George Vancouver's surgeon botanist, Archibald Menzies, and some of the plants he found on these Pacific Northwest shores, in particular, one plant of the four genera in the Ericaceae that he was the first to collect - Rhododendron macrophyllum . Menzies' botanizing covered the shoreline areas from a point just east of where Port Angeles now stands, east to Port Townsend into the Hood Canal, to the sites of Tacoma and Olympia in Puget Sound, to Whidbey and Camano islands and the San Juan Islands, up Georgia Strait to Cortez Island and Desolation Sound, continuing across to Quadra and Vancouver islands to Johnstone Strait (see map page 128).

He botanized at Menzies Bay on Vancouver Island before the party tackled Seymour Narrows. The only new plant he found there was a penstemon, Penstemon menziesii . Menzies found the natural productions of the country "exceeding barren". So much for the flora of Vancouver Island.

It took Discovery and Chatham two days to make it through the channel between Quadra and Vancouver islands, tacking back and forth at high and low tide slacks, having to anchor between times so as not to be driven back into the Strait of Georgia by the exceptionally strong tidal currents and rips.

The party then sailed out of Johnstone Strait and into the south end of the myriad island and rock strewn Queen Charlotte Sound. Both ships foundered on rocks at the north end of this waterway where it joins Hecate Strait.

From an anchorage at the Broughton Islands, with trips up Knight Inlet and Rivers Inlet with Mr. Puget, Mr. Whidbey, and Mr. Broughton, Menzies botanized the shores of British Columbia's most rugged terrain. Even today this area of the coastline is still only accessible by float plane or boat. Rivers Inlet was named, not for the many rivers that flow into it - there are a dozen - but after George Pitt, the first Baron Rivers of Strathfieldsaye in Hampshire.

Continuing north they went through Fitzhugh Sound into Burke Channel around Menzies Point, passing by the arm into Bella Coola and turning into South Bentnick Arm and back out across Hecate Strait into the Pacific. Then they followed a long series of northeast tacks and sailed into Nootka for the quiet, first confrontation with the Spanish. In fact, it was the occasion for a joint sortie up to Tahsis to attend a great soiree held by Chief Maquinna.

|

Surgeon Turns Botanist

Why Archibald Menzies, the naval surgeon, became the botanist on the Vancouver voyage requires an explanation here. Menzies was sent out by Sir Joseph Banks as his third collector. Banks had sent Francis Masson to Africa, Spain and the West Indies and Peter Thunberg to follow him. All three were to further his great scheme for the King's Garden at Kew - to make it the world's greatest assemblage of plants, living and dead.

The king was George the Third who had "lost" Britain her American colonies. Banks achieved his goal for Kew Gardens, although not until after his own death and the demise of "Crazy" George.

Sir Joseph Banks had known Menzies from the time when Menzies was surgeon on the Halifax (Nova Scotia, Naval Station) and had sent Acadian plants back home to the great amateur naturalist.

Banks was also his own collector in Newfoundland, going there in 1766. In the fishing camps on this Atlantic island, he found the recipe for the "sailors life-saver", spruce beer. He gave this recipe to Menzies for the Vancouver Voyage so that several times Menzies was able to botanize when the brewers went ashore from a Discovery and Chatham anchorage to brew up a hogshead or two.

As the brewers were never sure of which spruce to use, they always called Menzies ashore to identify the type of spruce boughs and needles they should use for the brew.

Since spruce, fir and pine were very loose terms used by Menzies covering all manner of conifers species that he found and since the short needle black spruce that the Bank's recipe called for does not extend anywhere into the Pacific coast tidewater areas, Menzies probably selected either western hemlock, Tsuga heterophylla (it has needles similar in length to Picea mariana ), Douglas fir or Sitka spruce.

If the truth be known, any or all of the conifers Menzies found on the Pacific coast would have made an equally potent scurvy preventing brew. This would also include our red cedar, or western arborvitae; after all it is the same genus as the eastern arborvitae.

Banks Gives Instructions

Menzies' instructions from Sir Joseph reads like a university calendar for courses in geography, botany, agriculture and linguistics. It begins: "You are to investigate the whole of the natural history of the countries visited, paying attention to the nature of the soil, and in view of the prospect of sending out settlers from England, whether grains, fruits, etc., cultivated in Europe are likely to thrive. All trees, shrubs, plants, grasses, ferns, and mosses are to be enumerated by their scientific names as well as those (names) used in the language of the natives (something Menzies seems not to have done). You are to dry specimens of all that are worthy of being brought home and all that can be procured, either living plants or seeds, so that their names and qualities can be ascertained at His Majesty's gardens at Kew."

Sir Joseph's instructions to Menzies continues: "Any curious or valuable plants that can not be propagated from seeds you are to dig up and plant in the glass frame provided for the purpose." The "glass frame" was also Banks' design and creation. These Banks frames or hutches were usually placed on the after end of the ship's quarterdeck. The one built on the after deck of Discovery was a 7 x 13-foot "box" that sat on the deck, which also served as the floor of the structure. The 3-foot high sides consisted of a sill or curb with four sliding, light sash (the only glass) and alternating wood panel paired shutters.

The top of the hutch was of four removable wood open grid gratings, similar to a ship's hatch covers, supported by and fitted onto two longitudinal beams. Inside there was a bench which held rows of clay pots by the rims and several 10-inch deep trays along with openings in the center of the bench so that a person could stand in them and tend the plants.

While the appearance of this plant frame was appropriately ship-like, it was never a very successful environment for transporting plants and keeping them alive, neither providing plants with sufficient light and sunshine nor keeping out deluges of water. It seems though to have kept plenty of water inside. A south Atlantic downpour on Discovery's return home in 1794 flooded out all Menzies' plants, which sloshed around as if in a great bath tub. It seems there were no outlet scuppers with backwater flaps in the sill for the water to flow out onto the deck.

It is surprising that any plants at all survived the voyages in these open grating topped hutches before Dr. Ward's sealed glazed cases came into use in the early 1840s.

|

|

A replica of the Banks plant frame at the

Van Deusen Garden, Vancouver, B.C., Canada Photo by Paul Weissman |

Captain is Reluctant

To say that Captain Vancouver was more than a little reluctant to have Menzies as a botanist with the voyage is understating the case. However, because of the great influence of Sir Joseph Banks with the Navy Department and his having the ear of the King concerning the Kew Gardens project, Vancouver reluctantly acceded to having Menzies aboard.

Only once or twice did Vancouver have Menzies with him on his cutter during Menzies' many botanizing sorties. These trips were a part of the charting along the shores from the ship's boat over the four months, May to September, 1 792. Menzies regularly went with the ship's officers, Mr. Peter Puget, Mr. Whidbey, Mr. Broughton (Master of the Chatham), Mr. Johnstone and Mr. Zachary Mudge, who along with Vancouver all led the coastal surveying and charting trips at one time or another during the four months.

Only Mr. Johnstone and Menzies had been to the north Pacific coast previous to 1792. This was in 1787 with Captain Collnett when Menzies named the island that is directly across Hecate Straits from the Queen Charlotte Islands "Banks Island" after guess who? Mr. Johnstone found the west end of the strait Vancouver named after him.

False Azalea Found

It is rumored that

Rhododendron camtschaticum

occurs on this 45-mile long 10-mile wide island at the outside of British Columbia's north coast that Menzies named after his patron. Not so, I'm afraid. What does occur on Banks Island that Menzies found and collected there is an ericaceous species that was named for him by Sir J.E. Smith. It is the false azalea,

Menziesia ferruginea

, a fine foliage plant and one of five known species, three native to Japan and one to the eastern United States.

I first came upon Menziesia in its native habitat during a dry autumn some four decades ago, the sun catching the golden and burnt sienna of the turning foliage. I was most taken with this shrub, but it was a disappointment the following spring, as the flowers were hidden away under the leaves and were hardly as large as the individual flower in a spray of 'H.E. Beale' heather.

To return to Vancouver and Menzies, perhaps the one and only time they were together on shore trip was the second time they went ashore - when they entered Juan de Fuca along the south shore of this strait. We landlubbers think of it as the north shore of the Olympic Peninsula.

It was also the second Juan de Fuca anchorage for Discovery and Chatham - in a calm island-protected north-south cornucopia shaped inlet that Captain Vancouver named "Discovery Bay" after his ship. Vancouver and Menzies grounded the cutter at the head of the inlet and stepped on the mud flats left by the receding tide. It was here that Menzies discovered three members of the Ericaceae growing together along the open gravelly shoreline at the edge of the dense coniferous forest that stretched for miles south and west right up to the snow line of the Olympic mountains.

These three plants were the arbutus or Pacific madrone, the hairy or Columbia manzanita and the Pacific rhododendron. The first was given the species epithet menziesii by Fredrick Pursh, who classified and named the plants from the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1805. Pursh was invited to undertake a flora of Canada, but a few weeks after his arrival in Montreal he fell ill and died there in 1820.

Arbutus menziesii had first been discovered at the southern end of its Pacific coast range among the Torrey pines just north of Mission San Diego by Spanish Friars. The Spanish kept this 32-year-old discovery, as with all their discoveries, secret. This was a church directed process where everything ended up in files in Seville. So the Pacific madrone, as named after Menzies, was the first to be published.

Menzies described the arbutus as the oriental strawberry tree and noted the hairy manzanita as an arbutus. While they are closely related, this latter is an Arctostaphylos . In Spanish the common name "manzanita" means "little apple". Nomenclature and taxonomy has improved since those good old days.

A note in passing: the hairy manzanita, the Pacific rhododendron and the Pacific madrone still occur together to this day on the Highway 101 roadside cuts at the head of Discovery Bay. All seem to love the well-drained sunny, sand and gravel soil slopes there.

When Menzies first saw the Pacific rhododendron at Discovery Bay it was not in bloom, as the date was only the 2nd of May. However, when he did see it in bloom in the month following, either on Bainbridge or Whidbey Island, his journal entry for June 6th reads, "We also met here pretty frequent in the wood with that beautiful native of the Levant the purple rhododendron."

So you can see that from the very first the Pacific rhododendron, Rhododendron macrophyllum , got off to a pretty poor start, at least in the pages of his journal, by being compared with a very familiar and common British Isles native, R. ponticum , although in 1792 it was not as yet considered a weed or spurned for its common mauve flowers. This didn't happen until almost a 100 years later.

As we shall see, the epithet "macrophyllum" given by David Don, turned out to be a complete misnomer in a botanical sense. The Pacific rhododendron was the third of the non-European/Asia Minor rhododendrons to be collected and described after R. catawbiense and the also misnamed, R. maximum , both from the wilds of the Atlantic coast of North America. What really "did in" Rhododendron macrophyllum , however, were the Hookers of Kew.

|

|

R. macrophyllum

at Rhododendron Lake,

Vancouver Island, British Columbia. Photo by Lynn Thompson |

Following is an excerpt from the journal of Archibald Menzies written on May 4, 1792, the day he first saw Rhododendron macrophyllum which he compared to and called R. ponticum .

On the 4th I landed opposite to the ship to take an excursion back into the woods which I had hardly entered when I met with vast abundance of that rare plant the Cypropedium bulbosom which was now in full bloom and grew about the roots of the Pine Trees in very spongy soil and dry situations. I likewise met here with a beautiful shrub - the Rhododendron ponticum and a new species of Arbutus with glaucous leaves that grew bushy and 9 or 10 feet high, besides a number of other plants which would be too tedious here to enumerate.

In this day's route I saw a number of the largest trees hollowed by fire into cavities fit to admit a person into, this I conjectured might be done by the Natives either to screen them from the sight of those animals they meant to ensnare or afford them a safe retreat from others in case of being pursued, or it may be the means (?) they have of felling large trees for making their canoes by which they are thus partly scooped out."

(To be continued in the JARS v45n4)

Clive Justice, Director of ARS District 1, landscape architect, park and display garden planner and government advisor, has recently returned from a seven-tour stint as a volunteer consultant/advisor in Malaysia with the Canadian Executive Service Organization. Six of the tours as a volunteer were with the Parks & Recreation Department of Kuala Lumpur, the capital of Malaysia, advising and overseeing the development of three display, education and conservation gardens. Most recently Mr. Justice was involved in the redevelopment and restoration of Kuala Lumpur's historic Padang (Independence Square). He is a charter and life member of the Vancouver Rhododendron Society, a chapter of the ARS, and a recipient of the ARS Bronze Medal.