JARS v46n1 - Tips for Beginners: Good Soil Promises Rhody Success

Tips for Beginners: Good Soil Promises Rhody Success

Harold Greer

( The following article is the third in the series Tips for Beginners. This article on soil was compiled from Greer's Guidebook to Available Rhododendrons by Harold Greer, a past president of the American Rhododendron Society and owner of Greer Gardens in Eugene, Oregon. )

"Rhododendrons are forgiving plants, but there are some things they just won't tolerate. So, it is important to understand their basic requirements," Mr. Greer tells the newcomer to rhododendron gardening.

The three basic requirements he lists all hinge on the quality of the soil in which - or on which - the rhododendron is planted. First, he says, they must have a constant supply of moisture. Second, they must never sit in stagnant water. And, third, they must be grown in a coarse, acid medium. Provide these conditions and you will succeed in growing a healthy rhododendron no matter where you live, provided the hybrid or species is suited to the climate, he promises.

Then he goes on to tell you how to provide these conditions. One distinction to note here is that the "planting medium" and the "natural soil" may well be two different substances in your garden. You will provide the planting medium, while nature provides the natural soil, which is usually a less than ideal soil for rhododendrons.

Mr. Greer then tells you to go outside and take a look at your soil. "Consider the growing medium (the improved top layer of soil if there is one) and also the soil and drainage that is underneath the proposed planting. You must determine whether or not your soil has good drainage. If heavy clay is present you must overcome this barrier. Dig a small hole and run some water into it; if the water does not disappear in a very few minutes, you have poor drainage. This is not a sure test, but it will give you a good indication. Now examine the soil texture; is it sandy, or is it composed of fine clay particles? Sometimes the topmost soil layer will drain well, but there will be a hardpan underneath it that will not drain. So, watch for this condition."

If your natural soil is perfect rhododendron soil, you can put this article down and take up your shovel and proceed. There are such soils (see Clarence Barrett's article on his garden on Nelson Mountain; Vol. 45, No. 2), but most are not so fortunate.

What most soils need is air, as Mr. Greer goes on to explain. "First, something is needed that will provide adequate air spaces in the soil, and the slower this material decomposes the better. Second, something is needed that will hold a certain amount of water so that the plant does not dry out too rapidly. Barks are generally quite good, as they usually contain both fine and rough textured materials. However, the much heavier, coarser bark rock will not work well for this purpose, although it will work as a mulch (mulches will be discussed in a later article). Since they are on the outside of the tree, constantly exposed to the weather, nature has endowed barks with a sort of natural preservative which slows their breakdown. The breaking down process of organic material requires nitrogen; consequently, the faster it breaks down, the more nitrogen it uses.

"Sawdust often breaks down very fast and, therefore, requires a lot of nitrogen. Some types tend to hold too much free water around each particle and can cause conditions that are too wet. This is particularly true in hot, wet summer areas and probably contributes to the myth that sawdust will kill a rhododendron.

"Leaves and needles of most kinds of trees are okay, although some kinds do break down rather fast and can be a hiding place for insects and diseases. Nut shells, spent hops, corn husks and a multitude of other things will work well as long as they are not alkaline and do not have toxic materials in them. If you do not know whether or not the material has been used with rhododendrons, try a small quantity for a time before going all out.

For the finer water holding part of the growing medium, the choice is often peat moss. In some areas good local peat moss is available, but in recent years good peat moss has been difficult to obtain, and often the powder that is sold as peat moss is worse than none at all. This is particularly true if you use only this very fine peat moss to mix with clay soil. The result will be a soppy soil that has no ability to hold air. Try to obtain the coarse nursery grind."

The next step is to mix the growing medium in which you will place the rhododendron. Mr. Greer goes on to tell how. "The old formula of one third sawdust or bark, one third peat moss, and one third garden loam* is all right, providing the humus material (sawdust, etc.) is coarse enough to supply the necessary amount of air in the soil. Up to one third of the soil volume should be air space, so use common sense to provide a mix that will give you this result. Almost any combination will work as long as it provides the necessary air.

"Remember: The slower the humus breaks down the better because the longer those particles of humus are there, the longer the soil is going to contain a lot of needed oxygen (in the air spaces). And, remember that organic material which breaks down too rapidly consumes lots of nitrogen, which is going to have to be replaced."

|

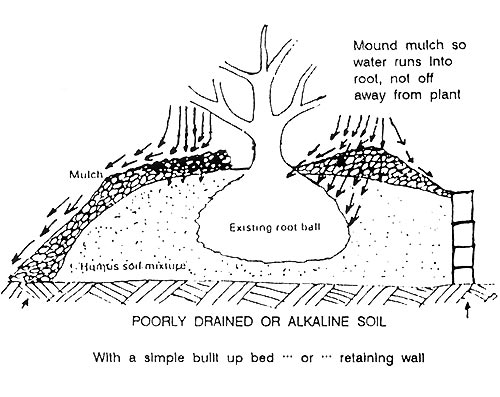

Now the question is what to do about the native soil. Mr. Greer gives these instructions. "We have already determined how to tell if we have good or bad drainage. If it is good, we can mix our planting medium into the top 6 to 10 inches of soil and we are ready to plant. We are also assuming that the native soil is acid (a subject of a later article). If the drainage is poor (and this is true in many locations) we will need to plant nearly on top of the native soil (see illustration)."

*(Editor's note: "Loam" is a term applied to soil which has a mixture of large (sand), medium (silt) and small (clay) particles. It refers to the texture of the soil, not its fertility or amount of organic matter in it.)