JARS v47n4 - Exploring Rhododendron Sanctuaries in Sikkim

Exploring Rhododendron Sanctuaries in Sikkim

Sue Muller Hacking

Redmond, Washington

Chip Muller

Seattle, Washington

"Stop the bus! There it is! Dalhousiae! "

Beside the narrow dirt road on a scruffy stump, and suspended over a precipitous drop-off stood the first blooming specimen of a Sikkim rhododendron we had seen: the graceful white bell-shaped flowers of Rhododendron dalhousiae . Nineteen travel-weary Rhododendron Species Foundation members came suddenly to life as we vied for positions along the road. We were a diverse lot, from 42 to 83 - doctors, scientists, housewives, engineers, professional and amateur gardeners, nursery owners. But what we held in common was a love of rhododendrons and a compelling desire to see them in their natural habitat - the Himalayas. At 6,000 feet the air felt deliciously warm despite the gathering monsoon clouds.

Our botanical guide, Mohan Pradhan, an orchid specialist, pointed out the cluster of white and yellow flowers nestled near the R. dalhousiae . "Coelogyne," he said. "One of the hundreds of Sikkim orchid species, and very fragrant."

We finished shooting photos and reboarded the bus, knowing we still had hours of driving. We were five days into our Sikkim adventure in May of 1992, and anxious to begin exploring the Himalayan forests for the more than 30 species first identified by Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker in 1848-1850. But patience is the name of the game in this almost inaccessible corner of Asia.

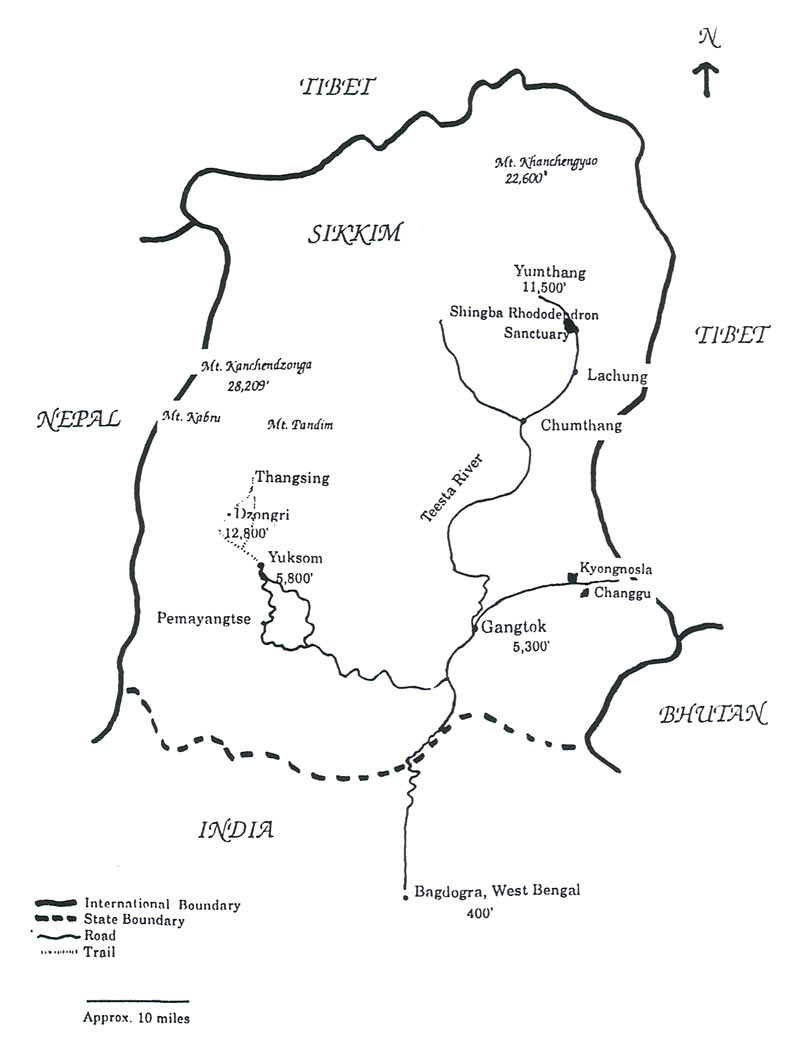

Traveling from the States to Sikkim involved a time-warping 23-hour flight across the Pacific to oppressively hot and humid Bangkok. A night's sleep, and a short flight to Calcutta began our Indian stay, where we had 24 hours to either rest or explore that vibrant and exotic city. Then on to Indian Airlines for the hop to Bagdogra, the nearest airport to the Himalayan foothills, and gateway to Gangtok, capital of the state of Sikkim.

Late in the afternoon of our third day we boarded Sikkim Tourism buses and left the dust and heat of Bagdogra (elevation 400 ft.) and headed for the hazy foothills that appeared dimly in the setting sun. We crossed the wide, muddy Teesta River and began our ascent as tiny lights appeared on the hillsides around us. The air cooled and filled with the scent of wood fires.

|

|

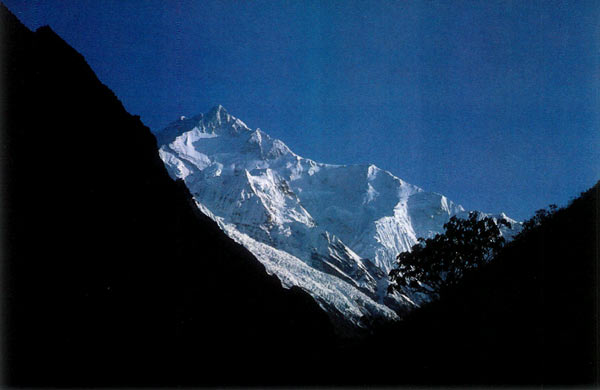

Mt. Kanchendzonga, 28,209 feet,

R. campanulatum Photo by Sue Hacking |

We awoke in the mile-high city of Gangtok to a world shrouded in pre-monsoon fog, and any hopes we'd had of viewing 28,209-foot Mt. Kanchendzonga faded in the white mist. We met briefly with our hosts, Mr. Keshab Pradhan, Consultant to the Government of Sikkim, Mr. P.K. Basnet, Chief Conservator of Forests, and Mr. Sailesh Pradhan, Tour Director for Sikkim Adventure. They brought the exciting news that after a five-day trek in western Sikkim, we would be granted unprecedented permission to visit rhododendron preserves in militarily restricted North Sikkim and East Sikkim. Our thanks go to Britt Smith of Washington who helped pave the way for this special permission through his years of rhododendron diplomacy and friendship with the forestry people of Sikkim. 1

During our rest day we acclimatized to the elevation by exploring Gangtok's open air market, flower show, and Sikkim handicrafts center. We feasted on Sikkim delicacies that evening at the country home of the Pradhans where we met other members of the Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker Chapter of the ARS, formed Oct. 25, 1991, including Sonam Lachungpa, Chief Forester of North Sikkim, and Udai Pradhan, authors of the newly published book, Sikkim-Himalayan Rhododendrons . We learned of the dedication of Sikkim's forestry department to preserving their botanical resources by creating sanctuaries, prohibiting commercial logging and educating children and adults about conservation. And we were anxious to see it in action.

|

We left Gangtok the next morning in two buses with our botanical guides, Mohan Pradhan and Sudhir Pradhan. As we zigzagged through a dizzying change of elevations we kept our guides busy with questions. What's the small lavender flower along the shoulder of the road? Wild turmeric. And the long-leafed plant that covers hillsides? Cardamom, Sikkim's number one agricultural export. Mohan showed us the 6-foot long stalk which produces small multi-flowered bulbs at the base. The seeds are hand-picked in September. Growing up to 9,000 feet, cardamom is well suited to the severe topography of Sikkim because it thrives on steep, shaded hillsides unsuitable for other agriculture.

Just before lunch we spotted the single R. dalhousiae . After that, not even hours of rain and hail from the Indian monsoon could dampen our spirits. The road ended at the village of Yuksom, which was one of the earliest capitals, seat of the Chogyal (Divine King) in the mid-17th century, and we settled into tents or bare rooms in the government-built trekkers' hut for the night.

Five a.m. brought the call, "Bed tea," and we wiggled out of our sleeping bags to be handed steaming cups of sweet, milky Sikkim tea. Above us stood the brilliant snows of Mt. Kabru, 24,006 feet. While we set up a city of tripods our Tibetan cooks spread a typical trekking breakfast buffet: hot oatmeal with crystallized sugar and warm milk, slices of omelet, toast with butter, peanut butter and mixed fruit jam.

Our first day's hike of 10 miles was to take us through forest from 5,800 feet to 9,800 feet, and we were to "anticipate a hot hike," said Sudhir. With a gentle clanging of bells our beasts of burden arrived - dzos (a cross between a yak and a cow). We made quite an entourage through the village - 19 trekkers, 17 dzos (16 to carry, one to ride), three ponies, four herders, four guides (Mohan, Sudhir, Thupten, and T.D.), two Sikkim Tourism policemen (who accompany all foreign groups), two cooks, and five kitchen helpers.

Within minutes we left the barley fields of the village and entered a naturalist's paradise. "We create awareness [among the people here] not to do away with the natural flora," said Mohan. "They only cut wood from the fallen trees. For fodder they use grass."

Mahonia, gentians, begonias, philodendrons, strangler fig, ferns, stinging nettles, and viburnum all made those of us from the Pacific Northwest feel at home. We traipsed beneath giant stands of bamboo, maple, oak and cinnamon trees. Violets brightened the ground and orchids perched on stumps and vine-covered trunks. From the dense canopy came the calls of the cuckoo and other birds. Pamela Smith, binoculars in hand, pointed out the flashing scarlet tail and yellow breast of the sunbird.

Traversing high above the Rathong river, we stepped often from our rocky trail onto sturdy, wooden planked suspension bridges which spanned small tributaries. Sudhir said the forest is home to pheasants, red pandas, Himalayan black bears and large, black-faced monkeys, but with the increase in tourism, and being the wrong season, we saw none.

Smaller beasts, however, made themselves unpleasantly visible when we stopped for lunch at the Chachin clearing, 7,200 feet: leeches. They first appear as needle thin, black lines, less than an inch long. When they've finished supping on human or yak blood they enlarge to as much as three inches and pencil thick.

To deter the creatures we tried (only somewhat effectively): salt water salves, insect repellent and tightly closed gaiters. When Rollo Adams opened his gaiters to reveal blood-soaked socks, he closed them up again and left the leeches to eat. Best prepared was Keith White who, having read an account of a British trek through leech-land, had donned queen-size panty hose. "Surprisingly comfortable," he quipped.

Deep in the lush forest we enjoyed the first of many hot lunches: puffed, fried bread (puri), spicy baked beans, curried potatoes and green peas, mini-sausages, processed cheese, small Tibetan apples, and, inevitably, tea with lemon and sugar.

After lunch we still had 2,000 feet to climb, but the Himalayan trails aren't so simple. As Herb Spady said, "Why not all up or all down?" After a series of short climbs followed by knee-shaking descents to cross ravines and the roaring Prekchu (river) we begin a relentless climb. Tired trekkers rode the ponies and Bill Ehret made friends with the saddled dzo.

|

|

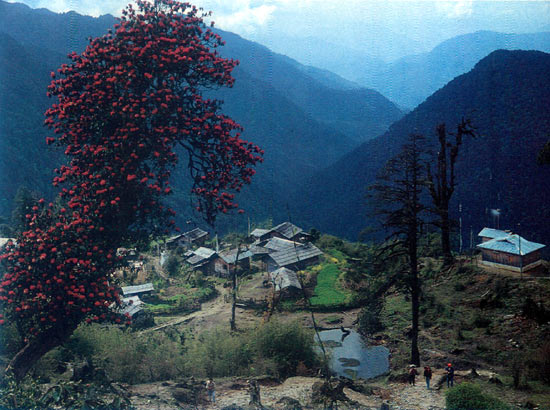

R. arboreum

, at Tshoka, 9,800 feet.

Photo by Chip Muller |

Mid-afternoon, at 8,300 feet we entered rhododendron territory. Immense moss-covered boulders encircled us and towering

R. arboreum

, studded with red trusses, formed a canopy overhead.

By late afternoon fog swirled round us, and graceful

R. falconeri

, with blossoms whiter than the fog, draped over the trail. Beneath our feet spread a carpet of blooming wild strawberries and clumps of arisaema, the latter being of special interest to Glen Patterson who grows several species at his home in Vancouver, B.C. Near dusk we arrived at the tiny village of Tshoka, elevation 9,800 feet, where we had supper, then collapsed.

Again the guides gave a cheerful call at 5 a.m. and we awakened to the glory of blue skies and Mt. Pandim (21,953 ft.) glowing with first light. Mohan gave his advice for the day. "Do not taste the nectar of the rhododendron or smell them because of the intoxication." A dark red patch on the hillside beckoned us - a fully blooming 30-foot R. arboreum , probably the single most photographed specimen on the trek! We passed that red sentinel of the forest and entered a paradise of hemlock, fir, and rhododendron. By 10,100 feet we were surrounded by a forest of R. arboreum , R. barbatum , R. grande , R. falconeri and R. wightii topped by gaunt but spectacular Abies spectabilis , the Himalayan silver fir.

The trail on which we walked - the main trekking route open to foreigners in Sikkim - was 7 years old and well maintained. Often we balanced on split logs which wound like a gentle staircase past the moss-covered trees and intertwined branches of rhododendron.

|

|

West Sikkim,

R. hodgsonii

forest, 11,500 feet.

Photo by Chip Muller |

At 10,500 feet we entered a band of R. hodgsonii with its smooth pink and peeling bark, and flowers varying from rose to reddish-purple. Interspersed with the larger trees we saw R. campylocarpum and R. thomsonii . Bob Grasing was amused to see the dzos munching on rhododendron leaves as they lumbered along the trail. From the back of her pony, Gwen Bell pointed out a steep, moss-covered boulder from which protruded a one-inch R. pendulum seedling with silver fuzz. Three days passed before we found one blooming. Another epiphyte, R. camelliiflorum , brushed our faces as we ducked under a silver fir log across the trail.

After trudging up what seemed like a dry waterfall (which Thupten, our Tibetan guide, called "nose-scratch climbing"), we emerged from the forest onto a grassy meadow at 11,750 feet. While the cooks prepared lunch on a fire of rhododendron branches we keyed out species such as R. thomsonii , R. campylocarpum , R. cinnabarinum , R. lanatum and R. wightii .

Trekking in the spring in the Himalaya offers the promise of blossoms, but the Indian monsoon, which can drop over 400 inches of rain in three months, can bring discomfort. Each morning's sunshine was soon replaced by cloud cover that wrapped us in dense white mist, falling temperatures, and rain. On our second day, as we slogged up the rocky, muddy trail the increased elevation brought hail and finally snow. Though vistas stayed hidden, we had the joy of the flowers. Rhododendron hodgsonii gave way to thickets of R. thompsonii , R. campylocarpum , and R. lanatum , then to hillsides of R. wightii , with their yellow flowers and light brown indumentum. On a 13,000-foot ridge we encountered R. anthopogon with its scented leaves and a few paper-thin blossoms, pink or yellow, and R. setosum and R. lepidotum , not yet in bloom, and a single blooming specimen of R. fulgens .

|

Hail pounded our shoulders and we clumped together in small groups, straggling into the Dzongri hut (12,800 feet) over a period of three hours.

Inside, we huddled in our parkas, for though the hut offered shelter from the wind and snow, it provided little warmth. We exchanged backrubs, swapped hail-storm stories, and aided by a single kerosene lantern, we keyed out botanical specimens. Just when we expected supper what appeared was a chocolate birthday cake for Donald King, president of both the Seattle ARS chapter and the Rhododendron Species Foundation. Dessert before supper seemed fine, especially when accompanied by glasses of potent Sikkimese rum.

That night Sally Sue and Dan Coleman, and Robert Barry and Don Selcer braved sleeping in snow covered tents. The rest of us spread our bags on wooden bunks inside the hut.

The 5 a.m. "tea ready!" call came too soon for our aching muscles, but with it came another, energizing call, "The mountains are out!" The air was crisp and clear after the night's storm and we began the 1,000-foot ascent to the summit of Mon Lepcha. Half an inch of fresh snow highlighted the blue-lavender trusses on head-high R. campanulatum that lined the trail. On the final push to the summit, where flags sent Buddhist prayers to the heavens, our boots crushed knee-high R. anthopogon releasing its pungent scent into the air. To the north rose the massif of the high Himalaya capped by the five-peaked holy mountain of Sikkim, third highest in the world: Mt. Kanchendzonga.

We savored each moment, for as we climbed, the monsoon crept in from the south to shroud the peaks. By 7 a.m. visibility was less than a mile and we returned to the Dzongri hut for breakfast.

We split up for the next two days, some remaining on the Dzongri ridge, while nine of us ventured farther north. We trekked through meadows decorated with juniper, minute primulas, meconopsis, potentilla, and androsace. The path wound between calf-high shrubs of R. anthopogon , R. setosum , R. lepidotum and impenetrable thickets of R. campanulatum . Repeating the elevation gains and losses of the previous day, we again passed through bands of R. campylocarpum and R. hodgsonii . At 12,000 feet we crossed the milky Prekchu on a cantilevered log bridge. We had lunch in a glen of R. wightii and hiked up an open, boulder-strewn valley where meconopsis, lilies, gentians, and creeping willow bordered clear streams.

|

|

R. hodgsonii

, 11,000 feet, North Sikkim.

Photo by Chip Muller |

The Thangsing hut at 12,600 feet offered protection from the afternoon rain, but we turned in early to escape the smoke-filled rooms. Morning sunlight shone on a valley of R. wightii and R. campanulatum , but our eyes were drawn to the head of the valley, where the Talung glacier, a convoluted river of ice, fell from Kanchendzonga.

For over 10 hours we enjoyed the best of Sikkim trekking on a new trail traversing the river valley. Sunshine brightened the fir, betula and rhododendron forest, and illuminated the snowy peaks. We strolled slowly, accompanied by the songs of the sunbirds and cuckoos, studying minute things that we'd passed before: brilliant Primula calderiana , ladybugs with myriad patterns on their backs, and single white flowers high in the vine-covered trees. Rhododendrons? Hard to tell from 60 feet below. Far off the trail Sue Hacking spotted a single white flower on a fallen log, and Chip Muller and Don Selcer waded through tangled branches and thorny shrubs to identify R. pendulum fallen from high up a moss-covered tree. A pale moon had risen over Mt. Pandim by the time we arrived at the Tshoka hut where the others were already sipping locally made millet beer from wooden mugs.

|

|

R. sikkimense

, believed by some to be a hybrid

between R. thomsonii and R. arboreum . Photo by Chip Muller |

On our fifth and final trekking day the monsoon moved in early. By 10 a.m. a mist settled; then the first raindrops fell. We force-marched in a wild downpour three hours to Yuksom, not even stopping for lunch. George Muller, riding a Tibetan pony, said, "When it's pouring and you're cold and you're stuck on the back of a pony - you sing."

From Yuksom we drove - soaked, leech bitten, but elated - to a beautiful hotel in Pemayangtse where the shower water wasn't quite hot, but the beds were dry. Then on to Gangtok where we stayed in the homes of our hosts, the Pradhans and their relatives. Electricity, hot showers and indoor plumbing. Ah, what luxury.

The following day we loaded up again, cleared the police check post north of Gangtok and entered a region forbidden to foreigners. Convinced of the sincere intentions of our group, the Sikkimese government extended us the privilege of visiting the Yumthang Valley for four days. At 11,500 feet, the lush valley lies south of the Tibetan border and the watershed of the Teesta and Rangit rivers.

|

|

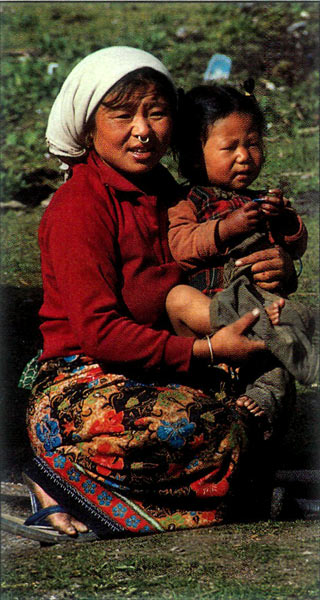

North Sikkim mother and child,

Yumthang Valley, 11,500 feet. Photo by Chip Muller |

We passed little traffic during our 12-hour drive north, but when we did, we often stared out into nothingness over thousand foot drop-offs to the river below. We crossed landslides as the road was being rebuilt, and passed signs reading "Regret Inconvenience" and "Love They Neighbor, But Not While Driving." Terraced fields of corn, rice, and barley cut neat steps into the hillsides, and waterfalls, too numerous to count, cut silver streaks on the green tapestry.

|

|

R. thomsonii

, believed to be the first discovered in the wild.

Photo by Chip Muller |

At the towns of Chumthang and Lachung, children ran from the shops and homes to greet us, probably the first group of Westerners they had ever seen.

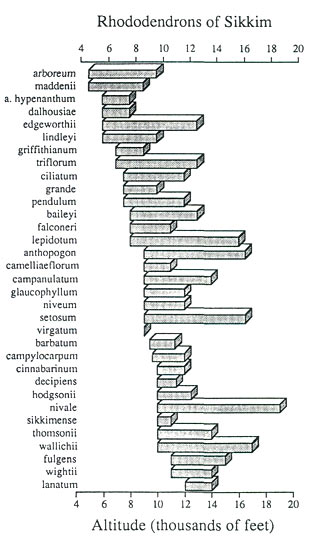

We stayed three nights in a private lodge, Yaktse, which nestled under towering cliffs at 11,000 feet with lavender-flowered R. niveum on the hillside behind. Each day our buses took us up through a band of R. hodgsonii to the Shingba Rhododendron Sanctuary (which encompassed only 10 acres in 1992, but as of this printing, has been enlarged to almost 10,000 acres). There, Sonam Lachungpa, acting as host and guide, led us through thickets of R. thomsonii , R. arboreum , R. campylocarpum , R. ciliatum , R. cinnabarinum , R. campanulatum , and R. glaucophyllum . Sonam specifically pointed out R. sikkimense , believed by some to be a hybrid between R. thomsonii and R. arboreum . Another exciting point was when Sonam found a white R. thomsonii , the first, we believe, discovered in the wild. 2 One afternoon, Don Selcer and Robert Barry found R. baileyi growing in dense mounds, with intense purple-magenta flowers and golden anthers.

|

|

R. cinnabarinum

, 11,500 feet.

Photo by Chip Muller |

Cheerfully munching a petal of R. cinnabarinum Sonam told us how the Sikkimese add these to curries for tangy seasoning, and ferment flowers of R. arboreum to make a liquor called guranse. The large R. falconeri leaves make excellent packaging for apples grown in the Lachung Valley, and leaves of the higher elevation specimens of R. thomsonii are used to make a strong insecticide.

Yaks and calves grazed the meadows, eating around perky clumps of Primula denticulata and P. atrodentata which especially delighted Dot Dunstan. And we were thrilled to find a blue Himalayan poppy, Meconopsis simplicifolia . Sonam led us along a well-worn path between the road and the river, saying, "This is the same trail J.D. Hooker walked 150 years ago. The river has changed in some places, but here it is the same - the old trading route between Sikkim and Tibet."

Each afternoon the monsoon sent us inside to sort seed, nap, and drink tea. But the mornings dawned bright and full of promise for catching sight of the snow-capped peaks of North Sikkim. On our last morning the Himalayan range stood in vivid relief against a blue sky, and we strolled through rhododendron and fir forest side-by-side with local Nepali-speaking families herding goats and setting out for a day's work on the roads. Two mornings later, back in Gangtok, the monsoon parted again and we saw majestic Kanchendzonga towering above the city.

With its abundant rainfall and astounding elevation change within its 2,800 square miles, Sikkim boasts a biological diversity perhaps unequaled elsewhere in the world. According to Lachungpa and Pradhan, Sikkim is home to over 4,000 flowering plant species, more than 500 species of birds and 400 species of butterflies, making it truly the garden of the Himalaya. As group member Sharon Leopold said, "I'm in heaven. I'm as close to heaven as I can get with my feet still on the ground."

1 As far as we know, only a handful of Westerners have visited this region: Britt Smith and Clive Justice came as guests of the government in 1990/91 and George Muller had trekked throughout North Sikkim in 1943.

For Clive Justice's account of his visit to Sikkim, see Vol. 46, No. 1 Winter 1992 issue of the ARS Journal.

2 A white R. thomsonii exists in Van Dusen Garden in Vancouver, B.C.

The May 1992 Sikkim trip was a family adventure for authors/photographers Sue Muller Hacking and Chip Muller, who are sister and brother. Their father, George Muller, also made the trip. George Muller had trekked in northern Sikkim for three weeks on R and R during World War II. He again visited Sikkim on the 1974 trip led by Britt Smith. He also accompanied Warren Berg on the 1986 rhododendron exploration to southeastern Tibet.

It was Sue Muller Hacking's second trip to Sikkim; her first was in 1974 when she also went with the team led by Britt Smith. She has also trekked in Nepal, climbing the 20,000-foot Mera Peak. She is a writer of children's fiction, has authored numerous non-fiction articles on travel, health, housing, people and recreation and has had her photographs published in magazines, textbooks, encyclopedias and calendars. She is a member of the Rhododendron Species Foundation.

The May 1992 trip was Chip Muller's first to Sikkim although his second to the Himalayas. He had accompanied Warren Berg on his 1986 rhododendron exploration to southeastern Tibet. He is a board member of the Seattle Chapter of the ARS and a member of the Photography Committee of the Rhododendron Species Foundation. The love of rhododendrons was passed on to both Sue and Chip by their father.