JARS 49n3 - World Survey of Rhododendron Powdery Mildews

World Survey of Rhododendron Powdery Mildews

Nicholas Basden and Stephan Heifer

Royal Botanic Garden

Edinburgh, Scotland UK

Introduction

Powdery mildews are fungal parasites of higher plants which may severely debilitate or even kill otherwise healthy plants through defoliation. They belong to the order of Erysiphales within the large fungal group, the Ascomycotina (Sac Fungi). Most powdery mildews spread on the outside of soft host tissues (leaves, young shoots, flowers and fruits) sending feeder cells (haustoria) into their hosts' epidermal cells. They thus extract water and nutrients from the host plant. Infected leaves of some hosts will wilt and eventually drop leaving the plant defoliated. Extensive defoliation may result in plant death. In less serious attacks hosts may only be debilitated but survive, and in other situations plants may be more or less immune to the disease.

The history of powdery mildews of rhododendrons in Britain goes back to the mid 1950s, when Prof. Douglas Henderson (personal communication) first discovered some diseased plants in the glasshouses of the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh. Independently powdery mildews were discovered on rhododendrons in Australia at roughly the same time (Anon, 1955). However, the problem in Edinburgh was eradicated, and no more mildew was discovered until 1969 when a new mildew appeared on plants of Rhododendron zoelleri , again in the glasshouses at Edinburgh (Watling, 1985). These plants had been introduced from New Guinea the previous year. Whilst it is unlikely that such an obvious disease should have escaped the watchful eyes of the collectors, an introduction of the fungus from New Guinea cannot be fully ruled out. On closer inspection of the new mildew it was noted that the conidia were significantly different from the previously discovered mildew on other species (Watling,1985).

In North America mildews of Ericaceae including Caultheria and Rhododendron have been reported as early as 1950 (Weiss). More specific reference to the mildews of Rhododendron species can be found in publications by Braun (1982, 1984, 1987) and, in more popular literature (Coyier et al. , 1986; Antonelli et al. , 1987; K. Cox, 1989; Cochran et al. , 1990, P.A. Cox, 1993). Nomura (1984) reports a different species of mildew from Japan, whilst Amano (1986) lists nine different mildew taxa (species) on 49 species of Rhododendron , occurring in 11 countries. In this survey these reports could not be verified (no positive specimens returned from Japan, Korea, Turkey, India, Netherlands or former USSR).

The recent increase in disease severity as well as host range (Brooks & Knights, 1984, Evans et al. , 1984, Minch, 1994, Heifer, 1994) has led to a new research initiative based at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh and involving a number of institutions and researchers. A grant by the American Rhododendron Society's Research Foundation in 1990/91 made it possible to assess the extent of rhododendron powdery mildew on a worldwide scale. For this purpose a questionnaire was sent to key institutions and individuals. This paper is the final report of results obtained from this venture.

|

Materials and Methods

QUESTIONNAIRES

Information was collected from returned questionnaires which had been sent throughout the world. In each questionnaire, information was requested on the following:

- place and date of collection;

- plant varieties;

- extent of damage (none, slight, medium, severe);

- first year of disease;

- control measures;

- other relevant information, e.g., growing problems, soil properties, etc.

A request for dried infected plant material was also made for examination and verification.

Ninety five different countries were targeted throughout the world - those where rhododendrons were known or suspected to be grown. Individual gardens/growers were chosen so that an even geographical distribution was achieved for each country. A list of all countries included and the number of questionnaires sent to each is presented in Appendix A.

An initial 707 questionnaires were sent to botanic gardens and rhododendron growers throughout the world. Subsequent mailings were sent to members of the International Rhododendron Union and other rhododendron groups and societies as well as chosen individuals. In all, 1,620 questionnaires were sent out, mainly in English but also in German, French, Spanish and Portuguese. Distribution was further enhanced by individuals passing the questionnaires on to friends or other growers, and by rhododendron societies including questionnaires in their mailings to members.

HOW THE DATA WERE ANALYSED

Information was extracted and processed a.) from answers to questions asked, e.g., which taxa were infected, controls used, etc., and b.) from additional information contained in the same replies, e.g., susceptibility of individual species, etc., geographical distribution, etc.

Any specimens received were examined using light and electron microscopy in order to verify the presence of powdery mildew and to determine the species. All specimens were retained for future reference (herbarium E).

Some problems were encountered in analysing the information received: i.) Not all questions were always answered or fully answered, ii.) Because of some ambiguity in the questions, the nature of the answers given was not always evident, e.g., in some instances it was unclear whether growers had listed all the species, etc., of rhododendrons in their gardens or merely those affected, iii.) Unless specimens were included no verification of the occurrence of powdery mildew could be made (some claims for the presence of mildew were found to be false). Most information therefore was accepted on trust. However, a great body of valuable information was received.

| APPENDIX A | ||||||

| World Distribution of Questionnaires with Returns and Results | ||||||

| Country | Number Questionnaires Sent | Number Returned | Positive for Powdery Mildew | Negative for Powdery Mildew | No Rhod. Grown | Questionnaires Wasted |

| Albania | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Argentina | 9 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Australia | 37 | 13 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Austria | 4 | 3 | 3 | |||

| Bangladesh | 2 | 0 | ||||

| Barbados | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Belgium | 8 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 1 | |

| Belize | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Bermuda | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Bolivia | 2 | 0 | ||||

| Brazil | 10 | 0 | ||||

| Bulgaria | 3 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Burma | 2 | 0 | ||||

| Canada | 19 | 13 | 6 | 6 | 1 | |

| Chile | 7 | 0 | ||||

| China | 29 | 8 | 3 | 4 | 1 | |

| Columbia | 13 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Costa Rica | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Cuba | 5 | 0 | ||||

| fmr. Czechoslovakia | 8 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Denmark | 5 | 3 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Dominica | ||||||

| (Commonwealth of) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Dominican Republic | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Eire | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| El Salvador | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Ecuador | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Finland | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| France | 20 | 5 | 1 | 4 | ||

| French Guyana | 2 | 0 | ||||

| Germany | 24 | 11 | 2 | 9 | ||

| Greece | 2 | 0 | ||||

| Grenada | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Guadeloupe | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Guyana | 2 | 0 | ||||

| Hawaii | 5 | 0 | ||||

| Honduras | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Hong Kong | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Hungary | 5 | 0 | ||||

| Iceland | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| India | 35 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Indonesia | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Iraq | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Iran | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Israel | 5 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Italy | 12 | 4 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Jamaica | 4 | 0 | ||||

| Japan | 23 | 31 | 4 | 27 | ||

| Java | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Kenya | 4 | 0 | ||||

| Malaysia | 8 | 3 | 3 | |||

| Martinique | 3 | 0 | ||||

| Mexico | 21 | 3 | 3 | |||

| Monaco | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Nepal | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Netherlands | 6 | 2 | 2 | |||

| New Zealand | 19 | 11 | 6 | 5 | ||

| Norfolk Island | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| North Korea | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Norway | 3 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Pakistan | 4 | 0 | ||||

| Panama | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Papua New Guinea | 4 | 0 | ||||

| Paraguay | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Peru | 4 | 0 | ||||

| Philippines | 7 | 0 | ||||

| Poland | 7 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Portugal | 4 | 0 | ||||

| Puerto Rico | 4 | 0 | ||||

| Reunion | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Romania | 4 | 0 | ||||

| Saint Helena | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Saint Vincent | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Samoa | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Singapore | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Solomon Islands | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| South Africa | 15 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| South Korea | 3 | 0 | ||||

| Spain | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Sri Lanka | 3 | 0 | ||||

| Surinam | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Sweden | 6 | 6 | 3 | 3 | ||

| Switzerland | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Taiwan | 2 | 0 | ||||

| Thailand | 3 | 0 | ||||

| Trinidad and Tobago | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Turkey | 5 | 0 | ||||

| United Kingdom | 35 | 21 | 12 | 6 | 1 | 2 |

| United States of America | 78 | 24 | 12 | 8 | 4 | |

| Uruguay | 1 | 0 | ||||

| fmr. USSR | 80 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 1 | |

| Venezuela | 7 | 0 | ||||

| Vietnam | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Virgin Islands | 2 | 0 | ||||

| fmr. Yugoslavia | 8 | 0 | ||||

| Totals | 707 | 213 | 69 | 105 | 35 | 10 |

Results and Discussion

Of the 1,620 questionnaires sent out 309 were returned (19% of the total). Of the 95 countries targeted 44 were represented by returned questionnaires (Appendix A). Of those distributed throughout the UK, 107 were returned.

With respect to mildew incidence 125 of those returned reported no sign of the disease on rhododendrons and 140 reported its occurrence. Locations with no rhododendrons accounted for 35 questionnaires, and 10 questionnaires were wasted.

Some 98 questionnaires were received enclosing 394 specimens. This material represented 237 different species, hybrids or cultivars. Of this 216 specimens have been positively identified as exhibiting powdery mildew. Overall, 355 species and hybrids/ cultivars were listed in the questionnaires returned as possibly being affected by powdery mildew. Those verified as positive for mildew are indicated in Appendix B.

|

|

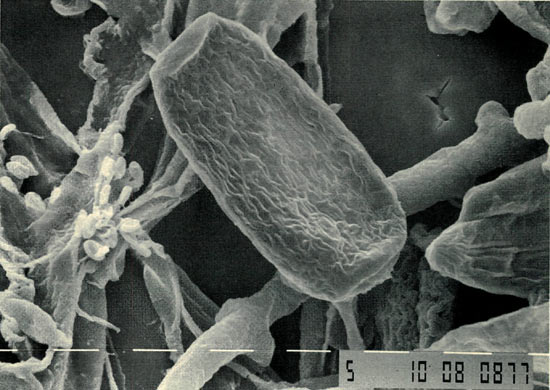

Figure 1. Conidium (asexual spore) of

Oidium

on

R. sessilifolium

.

Scanning Electron Micrograph; bar = 5µm. Photo by Nicholas Basden & Stephan Heifer |

TAXONOMY

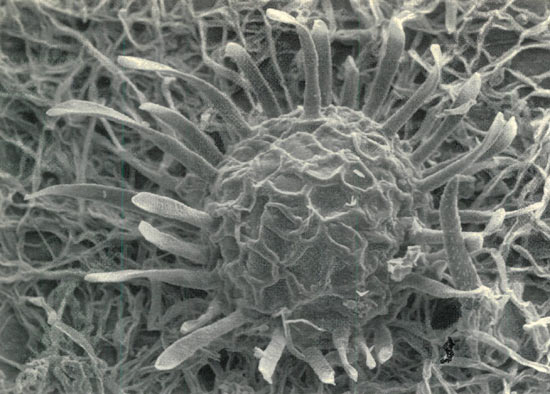

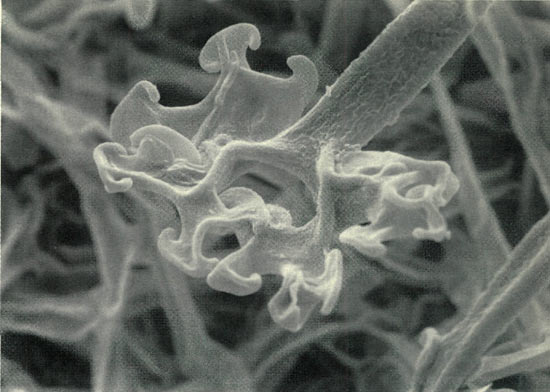

All European and Australasian specimens received - with one exception - proved to be of the Oidium type (Fig. 1) associated with Erysiphe cruciferarum Opiz ex Junell (Boesewinkel, 1981; Watling, 1985). All North American specimens 1 and one Belgian sample (originally from the USA) were identified as Microsphaera azaleae Braun (Figs 2 & 3). Other taxa may be involved (see Introduction) but could not be confirmed in this survey. The results discussed below should be considered with these taxonomic difficulties in mind.

|

|

|

|

Figure 2. Young cleistothecium of

Microsphaera azaleae

on R. mekongense . Scanning Electron Micrograph. Photo by Nicholas Basden & Stephan Heifer |

Figure 3. Mature cleistothecial appendage of

Microsphaera

azaleae on R. mekongense . Scanning Electron Micrograph. Photo by Nicholas Basden & Stephan Heifer |

CLIMATE

Although information submitted could not be said to constitute a definitive picture on all matters relating climate to powdery mildew some re-occurring points were evident. Please note that the understanding of "hot" and "wet," etc., may be much related to the observers' perception in a given geographical setting and should be interpreted accordingly.

Most frequent was the observation that the disease was evident or worse after a time of drought or periods of hot, dry weather: "two years of drought... encouraged mildew" (UK); "powdery mildew...only appears in warm dry spells" (New Zealand); "evident after four weeks of hot dry weather" (Australia); "after two dry summers...powdery mildew worse that year" (UK). (Conversely, one grower in the UK reported a 'Loderi', which had suffered severely, being "greatly improved following two dry summers").

With regard to rainfall, some felt that a "wet climate may work against powdery mildew" (New Zealand). One grower in South Africa noted that "heavy rainfall in summer does not permit mildew to become established". However, there was evidence enough in growers' reports to suggest that heavy annual rainfall per se is not a barrier to powdery mildew. Several locations reporting severe mildew attacks had a rainfall of up to and over 2500 mm/year (=100 inches) and the most dense occurrences of mildew in the UK appear on the northwest and southwest coasts - two of the wettest parts of the country.

That powdery mildew proliferates after both dry arid/or wet spells was reported by one grower in Washington State, USA who first attributed its outbreak to a "drier than usual spring" but, later reported extensive mildew damage after a "very wet fall."

Thus, although hot dry spells are obviously conducive to the occurrence and/or spread of powdery mildew it will also occur, even thrive, in wet or excessively wet climates. Interestingly, the UK grower whose 'Loderi' "greatly improved" after two dry summers also mentioned that during that same time he had applied a heavy mulch to the plant. Again this may be some indication that feeding may contribute to a plant's ability to resist attack - even in what appears to be optimum conditions for mildew occurrence.

Observations were also made that mild winters were conducive to the spread of the disease. Two locations, however, with winter temperatures of -40°C [= -40°F] (Canada) and -26°C [= -15°F] (USA) reported "slight" and "severe" attacks of the disease respectively, indicating the ability of this species or isolate to survive extreme cold.

Powdery mildews are known to survive and grow in extreme dryness (Braun, 1987; Butt, 1978), but spore germination is favoured by high relative humidity on the leaf surface. Conversely liquid water may reduce the survival ability of conidia (Peries, 1962), and it also hinders conidial dispersal which is mainly by wind. As long as host leaves or leaf buds are alive powdery mildews may survive very low temperatures (Butt, 1978), and some conidia may be stored at -60°C [-76°F] without loosing their infectivity; however, our own experience shows that this ability to survive extreme cold conditions seems to be different for the Oidium type compared with Microsphaera azaleae , and cold winters are considered to be controlling disease development (incidental observations by the authors). At temperatures exceeding 30°C [86°F] growth of most mildews is checked (Schnathorst, 1965).

SOIL

Few conclusions could be drawn from information received on soil characteristics, deficiencies, etc. This was partly because of the relatively low number of replies on this matter. An analysis of received information on the possibility of a link between powdery mildew occurrence and soil pH was inconclusive. There were, however, two secondary observations made from analysing the received information. Firstly, growers who had laboured to improve soil quality had consistently less severe manifestations of mildew. This would go some way to underline the point made earlier that the feeding of plants is an important control in itself in the fight against mildew attack. Secondly, those who described their soil or substrate as exhibiting “good drainage” more frequently reported severe attacks of the disease. In these cases, the low water retention of the soil may only be relevant to the occurrence of mildew when linked with periods of drought - again a stress related factor. Watering at appropriate times may therefore help plants ward off mildew attacks. It has to be taken into account, however, that in many host plants nitrogen fertilization and liberal supply of (irrigation) water leads to an increase of powdery mildew severity (Jenkyn & Bainbridge, 1978).

It is assumed that many growers did not return answers to the question on soil properties, etc., simply because they were unaware of them. Knowledge of these matters however may be invaluable in the overall fight against powdery mildew.

| Appendix B | |||||

| List of Affected Rhododendrons | |||||

| A | H | R | |||

| R. arboreum | England | R. hemsleyanum | Scotland | R. rex ssp. arizelum | Wales |

| R. augustinii | England | R. hodgsonii | Scotland | R. rex ssp. fictolacteum | Scotland |

| R. auriculatum | England | R. hookeri | England | R. rubiginosum | Scotland |

| 'Addy Wery' | London | 'Hilda Margaret'* | England | Rapture Group | USA, ? |

| 'Alison Johnstone' | England | 'Hotei' | England | 'Red Velvet' | USA, ? |

| 'Autumn Gold' | N. Ireland | Scotland | 'Repose' | England | |

| 'Hugh Koster' | Scotland | 'Richard Gill' | England | ||

| B | 'Riplet' | England | |||

| R. bakeri | USA, WA | I | 'Roberte' | England | |

| R. barbatum | England | 'Irene Koster' | England | 'Rosabel' | England |

| 'Bo-peep' | Scotland | 'Roza Stevenson' | England | ||

| 'Bow Bells' | England | J | Royal Flush Group | Australia, Melbourne | |

| 'Bridesmaid' | England | R. javanicum | New Zealand | England | |

| 'Britannia' | Scotland | Jalisco Group | England | ||

| England | S | ||||

| 'Broughtonii Aureum' | Australia, Tasmania | K | R. searsiae | Scotland | |

| 'Keay Slocock' | New Zealand | R. selense ssp. jucundum | Scotland | ||

| R. sessilifolium | Scotland | ||||

| C | L | R. simsii Planchon | China, Yunnan | ||

| R. campanulatum | England | R. lindleyi | England | R. sinogrande | Scotland |

| R. campylocarpum | England | R. lochiae | Australia | R. succothii | Scotland |

| R. ciliatum | Scotland | Melbourne | 'Scarlet Wonder' | Scotland | |

|

R. cinnabarinum

Blandfordiiflorum Group |

England | R. lutescens | Scotland | 'Seta' | Scotland |

| R. luteum | England | England | |||

|

R. cinnabarinum

Roylei Group |

England | 'Lady Bessborough' | England | 'Seven Stars' | England |

| Scotland | 'Lady Chamberlain' | England | 'Sir Frederick Moore' | England | |

| Wales | Scotland | 'Sir W.C. Slocock'* | ? England | ||

| R. cinnabarinum | N Zealand | 'Lady Eleanor Cathcart' | England | 'Silver Slipper' | England |

| USA, WA | 'Lady Rosebery' | N. Ireland | 'Snipe' | Scotland | |

| Scotland | England | 'Solent Swan' | England | ||

| England | 'Lionel's Triumph' | England | 'Souvenir de Dr S Endtz' | Scotland | |

| R. cinnabarinum hybrids | Scotland | Loderi Group | England | 'Souvenir of W.C. Slocock' | England |

| England | 'Loder's White' | Scotland | 'Strawberries and Cream' | USA, NY | |

| Australia, | 'Loderi Game Chick | England | |||

| Tasmania | 'Loderi King George' | England | T | ||

| New Zealand | 'Loderi Titan' | England | R. tashiroi | Canada | |

| R. cinnabarinum ssp. xanthocodon | England | 'Loderi Venus' | England | Ontario | |

| R. cinnabarinum ssp. xanthocodon Concatenans Gr. | England, Scotland | Luscombei Group | England | R. thomsonii | England |

| Scotland | |||||

| R. concinnum | Wales | M | R. triflorum | Scotland | |

| R. macabeanum | Scotland | 'The Master' | England | ||

| R. cyanocarpum | Scotland | R. maddenii ssp. crassum | England | 'Torch Bearer | Canada |

| 'Caerhays Philip' | England | R. maddenii ssp. maddenii | England | Dr Benesu'* | Ontario |

| 'Canta'* A G | England | R. mekongense | Scotland | ||

| 'Carita' | England | R. mekongense var. rubrolineatum | Scotland | U | |

| 'Carita Inchmery' | Scotland | R. mekongense Viridescens Group | Sweden | 'Unique' | England |

| 'Cecil S. Seabrook' | Canada, | R. molle | New Zealand | Unknown | England |

| Ontario | R. molle ssp. japonicum | Canada | |||

| 'Cecil S. Seabrook' | USA, ? | Ontario | V | ||

| 'Centennial | Vancouver | R. veitchianum ssp. cubittii Gr. | Scotland | ||

| Celebration' | England | USA, Phil. | R. viscidifolium | Scotland | |

| 'China' | England | R. moupinense | Scotland | "Vireya" | New Zealand |

| 'Cincrass' | England | R. myrtifolium | England | Australia, NSW | |

| 'Cinnkeys' | England | R. macgregoriae hybrids | Australia, Melbourne | 'Vanessa' | Scotland |

| 'Cilpinense' | Scotland | 'Margaret Dunn' | Australia, Melbourne | 'Vanessa Pastel' | Scotland |

| 'CIS' | Scotland | Mariloo Group | England | 'Virginia Richards' | Australia, Melbourne |

| 'Conroy' | N. Ireland | 'Martha Isaacson' | England | Scotland | |

| England | 'Meg Merrilees' | England | N. Ireland | ||

| Cornish Cross Group | England | 'Michael's Pride' | England | England | |

| Ireland | 'Moerheim' | England | 'Viscy'* | England | |

| Scotland | 'Moreia'* | England | |||

| 'Cornish Red'* | England | 'Morning Sunshine' | USA, WA | W | |

| 'Corona' | England | 'Mrs. Charles E. Pearson' | Scotland | R. wallichii | Scotland |

| 'Cunningham's White' | Scotland | 'Mrs. G.W. Leak' | Australia | R. wardii | England |

| 'Cynthia' | Scotland | Tasmania | R. williamsianum | ||

| England | England | hybrids | England | ||

| 'Mrs. W.C. Slocock' | England | 'White Gold' | England | ||

| D | N | 'White Swan' | USA, Conn. | ||

| R. davidsonianum | Scotland | R. neriiflorum | England | 'Windsor Lad' | England |

| R. decorum | England | Scotland | 'Winsome' | England | |

| R. decorum ssp. diaprepes | USA, WA | Naomi Group | Scotland | 'Wishmoor' | England |

| England | England | ||||

| R. dichroanthum | England | 'Naomi' AM | England | Y | |

| 'Diane' | England | 'New Comet' | England | R. yunnanense | England |

| 'Dopey' | England | 'New Moon' | England | Scotland | |

| Nobleanum Group | Scotland | Wales | |||

| E | Yunncin Group | England | |||

| R. eclecteum | Scotland | O | Scotland | ||

| 'Elizabeth' | Scotland | R. occidentale | New Zealand | ||

| England | England | ||||

| 'Elsie Straver' | N. Ireland | USA, CA | |||

| 'Emil Liebig' | England | R. occidentale 'Leonard Frisbie' | USA, WA | ||

| 'Evening Glow' | N. Ireland | R. orbiculare | England | ||

| Exbury azaleas | England | Scotland | |||

| 'Exbury Hawk' | England | R. oreodoxa var. fargesii | USA, WA | ||

| 'Exbury Naomi' | England | R. oreotrephes | England | ||

| 'Exquisitum' | England | 'Old Gold' | USA, ? | ||

| Omar Group | N. Ireland | ||||

| F | |||||

| R. falconeri | Scotland | P | |||

| R. flavidum | England | R. ponticum | Canada | ||

| R. fortunei | Scotland | Ontario | |||

| R. fortunei hybrids | England | Scotland | |||

| 'Fastuosum Flore Pleno' | England | England | |||

| 'Frontier' | England | R. praevernum | England | ||

| 'Peace' | England | ||||

| G | 'Penjerrick' | England | |||

| R. griffithianum | England | 'Phalarope' | Scotland | ||

| 'Galloper Light' | England | 'Pink Drift' | Scotland | ||

| Ghent hybrid | USA, NY | 'Pink Pearl' | Scotland | ||

| Gill hybrids | England | England | |||

| 'Golden Fleece' | England | 'Polar Bear' | England | ||

| 'Goldsworth Crimson' | New Zealand | 'Princess Anne' | England | ||

| 'Goldsworth Orange' | England | ||||

| 'Gracioso'* | England | ||||

| Gandavense Group | USA, NY | ||||

OCCURRENCE

Historic perspective

The indications are that people first became aware of outbreaks of powdery mildew in the early 1970s (earliest definite record was 1972). From that time, and through to the early 1980s, outbreaks were sporadic (e.g., none in 1973, '74, '76, '79). From 1984 onwards, however, a dramatic increase in the number of initial outbreaks of the disease occurred, with numbers remaining consistently high from that time and up to the present.

Occurrence with regard to taxa

Overall, 192 different species and hybrids/cultivars were positively recorded as being affected by powdery mildew (see Appendix B). Of this number 123 were hybrids and the remaining 69 species. The great majority of these were listed only once or twice. Only 13 individual species/hybrids were reported as positive for mildew on five or more different occasions; these were, in descending order:

1) R. cinnabarinum

2) R. thomsonii

3) 'Lady Chamberlain'

4) 'Elizabeth'

5) R. cinnabarinum ssp. xanthocodon Concatenans Group

6) R. cinnabarinum Roylei Group

7) 'Virginia Richards'

8) 'Lady Rosebery'

9) 'Alison Johnstone'

10) Loderi Group

11) 'Naomi'

12) Cornish Cross Group

13) R. campylocarpum

Deciduous azaleas and Vireya rhododendrons were also frequently cited.

In terms of susceptibility to attack, a similar list to the above emerges (thus discounting a high incidence as being merely indicative of popularity with growers). R. cinnabarinum , 'Lady Chamberlain', 'Elizabeth', R. thomsonii and 'Alison Johnstone' were most frequently cited as being the first to succumb or the worst affected along with Cornish Cross Group, 'Lady Rosebery', 'Virginia Richards', 'Seta', 'Penjerrick', 'Lady Bessborough' and 'Mrs. G.W. Leak'. Although this list is not exhaustive it gives some indication of vulnerability to powdery mildew. R. cinnabarinum is seemingly by far the most susceptible, the deciduous azaleas often the first to be affected.

Hybrids were often noted as being particularly prone to infection. This was especially so with progeny from (again) R. cinnabarinum , Loderi Group, 'Naomi' and R. occidental . Often, the more vulnerable hybrids are crosses from more vulnerable parents (e.g., R. cinnabarinum and 'Lady Chamberlain'), but this is not always the case. Some growers made note of the fact that only some R. cinnabarinum hybrids were susceptible. However, there is enough evidence to suggest that some inherited weakness with regards to powdery mildew attack occurs.

Rhododendron cinnabarinum and 'Elizabeth' were also noticeable as the two most likely to suffer fatally from infection. (But see also comments on 'Elizabeth' under Natural Recovery.)

The above mentioned are, however, only those most frequently noted as particularly susceptible. Others were also described as such by growers. A full list of species and hybrids positive for powdery mildew together with all these noted as being first affected and/or most susceptible appears in Appendix B. Observations on which species/hybrids may be less susceptible to attack were less specific. Those indicated by growers, however, as being free from mildew (amongst others where the disease was evident) and which reports were not contradicted by positive occurrence elsewhere are listed in Appendix C as a check list and data base for future records.

Rare reports of the disease not becoming a problem over a lengthy period were received from Canada: "has persisted on isolated plants for several years but not serious enough to be overly concerned" (harsh winters and ferrous sulphate added to soil may have had an effect), and New Zealand: "no control...only slight problem, plants still grow and flower well" (powdery mildew since 1989). One UK grower noted that amongst his collection "many...show some infection but it does not seem to get any worse." Another, citing Loderi Group and Venus Group as an example - stated "some vigorous varieties...have powdery mildew but appear to be sufficiently vigorous to carry it without dying" (but see comments on plant care under Control).

| Appendix C | |

| List of Plants Mentioned by Growers as unaffected | |

| Species / hybrids apparently unaffected | |

| R. albiflorum | |

| R. ambiguum | 'Lee's Dark Purple' |

| R. argyrophyllum ssp. nankingense | 'Leonare'*? |

| R. atlanticum | 'Lord Roberts' |

| 'Anna Rose Whitney' | 'Loudovic Iceberg'* |

| 'April Glow' | |

| 'Argosy' | R. maddenii 'Fender' |

| 'Arthur Ostler'? | R. megacalyx |

| R. micranthum | |

| 'Bad Eilsen' - 'highly resistant' | R. minus Carolinianum Group |

| 'Baden-Baden' | R. mucronulatum |

| 'Bibiani' | R. mucronulatum 'X-Ray' |

| 'Blewbury' | 'Mars' |

| 'Blueberry'* | 'Matador' |

| 'Boule de Flare'* | 'May Day' |

| 'Moerheim's Scarlet'* | |

| R. caucasicum | 'Mrs. A. T. de la Mare' |

| 'Carmen' | 'Mrs. Charles Thorold' |

| 'Catawbiense Album' | 'Mrs. Tom H. Lowinsky' |

| 'Cetewayo' | |

| 'Chinmar' | 'Nova Zembla' |

| 'Countess of Haddington' | |

| 'Countess of York'* | 'Old Port' |

| 'County of York' (syn. 'Catalode') | |

| R. pseudochrysanthum | |

| 'Dr A. Blok' | 'Palestrina' |

| Dragonfly Group | 'Pilgrim' |

| 'Pink Bountiful' | |

| R. edgeworthii | Pioneer Group? |

| R. edgeworthii as ( bullatum ) | 'Powder Puff'* |

| 'Eider' | |

| 'Etta Burrows' | R. quinquefolium |

| 'Everestianum' | |

| R. rubropilosum | |

| R. formosum var. inaequale | 'Red Carpet' |

| R. forrestii Repens Group | 'Redpoll' |

| R. fortunei ssp. discolor | 'Robert Allison' |

| R. fortunei 'Lu Shan'* hybrids | 'Rosy Morn' |

| 'Frank Galsworthy' | 'Royal Lodge' |

| 'Furnivall's Daughter' | |

| R. smirnowii | |

| 'Gene's Favourite' | R. strigillosum |

| 'Gibraltar' | 'Saint Tudy' |

| 'Goldworth Pink' | 'Sherwood Hill'*? |

| 'Goldsworth Yellow' | 'Snow Queen' |

| 'Grenadier' | 'Spring Magic' |

| 'Sweet Simplicity' | |

| R. horlickianum | |

| 'Herbert' | 'Tally Ho' |

| 'Tidbit' | |

| R. insigne | |

| 'Ilam Violet' | R. vernicosum as var. rhantum |

| 'Van Nes Sensation' | |

| 'Jabberwocky' | 'Vulcan' |

| Kalmia? | R. wightii |

| R. keiskei | Waterer hybrids? |

| 'Kilimanjaro' | 'Wheatley' |

| Kordes hybrid (pink) | 'White Olympic Lady' |

| 'White Pearl' | |

| R. lacteum (unspotted forms) | 'White Wings' |

| Loderi Group | 'Wilgen's Supreme'? |

| 'Lady Alice Fitzwilliam' | 'Windbeam' |

| 'Lavender Girl' | |

Other observations regarding resistance to attack were that large leaved plants and those with indumentum all appear less susceptible. Further observations on susceptibility or resistance were also received but do not have the same 'weight' of evidence in that they were noted on only one or two occasions. However, they are offered here as a possible general check list for those who may wish to make their own observations.

Negative or Less Susceptible

- Dwarf rhododendrons

- Triflora group/hybrids

- Asiatic rhododendrons

Some growers stated very broadly that 'lepidote rhododendrons' were less affected, whereas others stated the same fact for 'elepidote specimens'; clearly these broad observations were not always helpful.

Positive or More Susceptible

- Deciduous rhododendrons

- Glabrous or waxy leaved rhododendrons

- 'Soft' leaved rhododendrons

- 'Thin' leaved rhododendrons Watling (1985) produced a first list of mildew affected rhododendrons and mentions 30 affected species and 8 hybrids. Additionally a number of other ericaceous plants are mentioned. K. Cox (1989) confirmed many of these findings from a grower's perspective.

CONTROLS

One of the most frequent requests from those who returned questionnaires was, unsurprisingly, for information on controls. Information received on controls fell into 4 categories: i. Fungicides ii. Other chemical controls iii. Cultural controls iv. Natural recovery.

It should be noted that the information, offered here, is a synopsis of growers' own stated experience and is not given as a recommendation by the authors. Some fungicide applications may contravene national pesticide regulations and the authors renounce all responsibility for actions taken as a consequence of these results.

i.) Fungicides

By far the greatest number of replies to the question on control measures indicated some sort of fungicide. Appendix D shows all such controls used. In assessing the effectiveness of individual fungicides from the questionnaires, several difficulties arose. Most growers reported using two or more fungicides in combination thus eliminating the possibility of individual assessment. Further, because of the low incidence of some fungicides reported in the questionnaires, no 'body of evidence' could be amassed regarding their effectiveness. Those cited less often may therefore be equally effective as those which frequently re-occurred.

Two controls stood out as the most popular: Nimrod t (bupirimate & triforine) and Benlate (benomyl). Used alone, Nimrod t (bupirimate & triforine) was often reported as achieving excellent results. "Spraying throughout season gives almost perfect control" (UK), "one thorough application...appeared to halve infection" (1989 mildew severe, 1990 leaves clean). Two growers found it had "little noticeable effect" (UK) and "no great effect where disease already present" (UK). Benlate (benomyl) was cited as being used singularly by only two growers. One found it successful, the other after "repeated" spraying found reinfection occurring by mid winter-early spring. Bayleton (triadimefon) also showed a high success rate when used alone. One grower in a straight comparison found it "superior" to Benlate (benomyl) (Australia). Another applied it on a regular basis to R. cinnabarinum and reported the disease under control with only two or three plants out of 100 still affected (USA).

Other fungicides reported as being used singularly and which were reported as being successful were Nimrod (bupirimate), Funginex, Octave, Mildothane, copper sulphate and colloidal sulphur.

Bravo (chlorothalonil), Bayfidan (triadimenol) and Fungaflor (imazalil) were given negative comments by growers. The remaining fungicides listed in Appendix D if cited as being used singularly were unfortunately not accompanied by comments on their effectiveness. It must be remembered that, with the exception of Nimrod t (bupirimate & triforine) and Bayleton (triadimefon) the above fungicides, used alone, were accompanied by reports of their effectiveness (positive or negative) on only one, or at the most, two occasions. Also the possibility of the frailty of conclusions drawn from a consensus of opinion is shown by one grower whose experience was that Tumbleblite (propiconazole) (cited only 3 times) was more effective than 'Nimrod t' (bupirimate & triforine) (cited 25 times) and that "trials [with Safer's fungicide] indicate equality with other fungicides and [that it] may be more residual" (UK).

For those fungicides used in combination with others, assessment was impossible. Further to the performance of individual fungicides was the assessment of the effectiveness of spraying itself: A significant number of growers made the claim that spraying was only effective as a preventative and not a cure (e.g., see comments on Nimrod t [bupirimate & triforine] above) or at the most gave only temporary respite. In many people's experience, spraying programmes, unless constant, resulted in a reoccurrence of the disease at a later date. One grower stated that powdery mildew was eradicated by spraying fortnightly (with Funginex [triforine]) for two years and with occasional preventative sprays since (UK).

Thus spraying, using any one or more fungicides may well be beneficial but only with long term programmes, and only if one can afford the time and the expense!

| APPENDIX D | |||||

| Table of Fungicides used. Incidence = No. Times Cited in Returnee Questionnaires. | |||||

| Active Ingredient | Trade Name | Incidence | Not Stated |

Effectiveness*

+ve |

-ve |

| Benomyl | Benlate | 22 | 14 | 6 | 2 |

| Bupirimate | Nimrod | 6 | 5 | 1 | 0 |

| Bupirimate & Triforine | Nimrod T | 25 | 11 | 12 | 2 |

| Captan | Captan | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Captan & Penconazole | Topas | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Carbendazim | Bavistan | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Carbendazim & Triadimenol | Tiara | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Chlorothalonil | Bravo/Repulse | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Copper Sulphate | -- | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Cupric Ammonium Carbonate | Fungex | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Dinocap | Karathane | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Dithlanon & Penconazole | Topas (see above) | (included above) | |||

| Fenarimol | Rubigan | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Imazalil | Fungaflor | 10 | 6 | 3 | 1 |

| Magnesium Sulphate | Epsom Salts | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Myclobutanil | Systhane | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Penconazole | Topas (see above) | (included above) | |||

| Penconazole & Captan (see above) | Topas (see above) | (included above) | |||

| Penconazole & Dithlanon (see above) | Topas (see above) | (included above) | |||

| Prochloraz | Octave | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Propiconazole | Tumbleblite | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Sulphur | -- | 5 | 2 | 3 | 0 |

| Sulphur (Colloidal sulphur) | Safer's Natural Garden Fungicide | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Thiophanate-methyl | Mildothane | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Triadimefon | Bayleton | 11 | 5 | 6 | 0 |

| Triadimenol | Bayfidan (see above) (included with Tiara) | ||||

| Triforine | Funginex | 6 | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| Above information with reference to 'Pesticides 1991' and '1992' (Reference Book 500 MAFF and HSE, HMSO). | |||||

| Fungicides cited in questionnaires but not listed in 'Pesticides 91, 92' | |||||

| Saprene | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sybolt | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| * Numbers indicating 'effectiveness' include incidents where the fungicide was used both singularly and/or in combination with others. | |||||

ii. ) Other chemical controls

Two other chemical controls were cited: Epsom salts (magnesium sulphate) and sulphur. Epsom salts used as a top dressing may well contribute to a healthy plant, more able to fight off disease. Only one grower who used Epsom salts in the absence of other controls commented on its effectiveness.

Sulphur, as a control for powdery mildew has a small but dedicated following and can be used either as a top dressing or to dust leaves with (strictly speaking a fugicidal treatment). One UK grower who used no fungicides but dosed the soil with sulphur and who previously had suffered severe powdery mildew attacks reported being "completely free" of the disease on those same plants at the time of communication. Others were also convinced by the efficacy of sulphur.

Information on the legal use of sulphur may be necessary in order to comply with pesticide regulations; however, according to one report offered, flowers of sulphur can be used as a fertilizer and there is "no restriction on height of application" (UK).

iii.) Cultural Controls

Interest in cultural controls, as an environmentally safe alternative to chemical controls was expressed by some who returned questionnaires. In turn, information relating to cultural controls received from growers encompassed two methods: a.) pruning and b.) ventilation.

iii a.) Pruning. Removal of infected leaves (or plants) was considered by some as an effective control. This was especially the case where the disease was rampant and fungicides seemed to have little or no effect. A grower in Tasmania, Australia reported his "nursery stock relatively clean" by removal of infected leaves alone. Another, from Washington State, USA cut two large and severely infected 'Virginia Richards' down to the ground and after two years reported the resurgent growth on one of them symptomless. (See also notes on natural recovery). Far from being a last resort, removal of leaves and/or plants may be also considered as the quickest way to arrest the spread of infection throughout a collection.

iii b.) Ventilation

From growers' reports this has proved to be the most successful control. The increase in ventilation in glasshouses and in the passage of free air in outdoor environments has produced some spectacular results. Observations of powdery mildew flourishing under windless conditions were substantiated by growers who propagated under glasshouse conditions - "powdery mildew appears under glass all year" (New Zealand) and "powdery mildew in plants...in shade-house conditions [but] garden... still free" (New Zealand). The effect of increasing ventilation was recorded by one grower in the USA - "had a lot of mildew...until I put in a fan jet for air circulation."

Similar observations were recorded for outdoor conditions. Many observed that mildew was more evident in places of heavy shade, i.e., where the overhead canopy was more dense or, conversely, less evident in open aspects where there was a greater passage of free air. Significantly, the above mentioned New Zealand grower who reported powdery mildew in the shade-house but none outside, described his garden as "young...still fairly open with overhead canopy still not very developed." A report on the consequences of thinning of overhead cover was received from one grower in the UK who suffered severe infection in 1985/86 with quite extensive defoliation and about 80% loss of his collection. After thinning and at the time of filling out the questionnaire he reported only four or five plants still affected.

iv. Natural recovery

Reports of natural recovery are encouraging. One grower passing on the experience of others, stated that some had seemingly suffered "an odd bad season followed by apparently natural recovery." Others' experience seems to support this. One UK grower reported outbreaks on 'Elizabeth' with the older plants dying but the younger plants making excellent recovery - no fungicides were used. Another who suffered severe mildew attack 5-8 years ago reported it as less severe in recent years - again no fungicides had been applied.

'Elizabeth' and 'Lady Chamberlain', interestingly, are two of the more susceptible rhododendrons - their ability to fight back is reassuring and it may be that they are particularly hardy in that respect.

In considering natural recovery as a form of control it is also worth addressing the question of plant care. Some growers were at pains to point out that this aspect was often overlooked when considering controls. It is a simple truth that a well looked after plant is less likely to succumb to disease or, if infected, probably more resilient. Indeed the initial outbreaks of mildew especially may, in many cases, be attributable to plant stress induced by drought and/or poor soil. Requisite watering and feeding, if possible, should certainly be considered (see also comments above regarding soil and climate).

The use of pesticides to control plant diseases is governed by national legislation (e.g., Control of Pesticides Regulations 1986 and Food and Environment Protection Act 1985 for the United Kingdom); additional legislation applies where hazardous substances are involved (e.g., Control of Substances Hazardous to Health Regulations 1994) , and growers should ensure that they do not fall foul of the law when applying control chemicals. In general, regulations for amateur products are less stringent than those for professional use (Anon 1994). Many authors of plant disease manuals favour the use of chemicals to control powdery mildews on shrubs and trees (e.g., Phillips & Burdekin 1982; Coyier & Roane 1986; Bigre ey al. 1987; Agrios 1988). However, others like K. Cox (1989) and P.A. Cox (1993) suggest a good compromise between chemical and cultural control methods in their more general publications for rhododendron husbandry.

Cultural control methods like pruning are recommended to check a number of diseases, including powdery mildews (Pirone 1978, Buczacki & Harris 1981; Antonelli et al. 1987). Minch (1994) recommends the combination of pruning with fungicidal treatment. In the long term the breeding and selection of mildew resistant cultivars may be the only solution. For obvious reasons, wherever possible the environmentally friendliest control method should be chosen in gardens open to the public.

Conclusions

Powdery mildews on rhododendrons are troublesome diseases, widespread over the areas where this beautiful genus is cultivated. Whilst there are regions which apparently do not harbour the diseases (most of continental Europe) it is very unlikely that these highly mobile pathogens will not eventually spread to the limits of their respective climatic distribution. For future breeding programs this should be kept in mind as one of the desirable characters of new hybrids. Control of the disease is possible but once established the pathogen will be difficult to eradicate from a planting. Further research currently undertaken in Scotland will hopefully provide more guidance on tackling the diseases.

Acknowledgement

The authors gratefully acknowledge the receipt of a grant from the American Rhododendron Society Research Foundation.

References

Agrios, G.N. Plant Pathology. 3rd Ed. Academic Press San Diego; 1988.

Amano, K. Host range and geographical distribution of the powdery mildew fungi. Japan Scientific Societies Press, Tokyo, 741 pp.; 1986.

Anon. Agricultural Gazette NSW 65, 100-103 (Abstract in Review of Applied Mycology 34, 435.); 1955.

Anon. Pesticides 1994. HMSO London;1994.

Antonelli, A.L.; Byther, R.S.; Maleike, R.R.; Collman, S.J.; Davidson, A.D. How to identify rhododendron and azalea problems. Washington State University; 1987.

Bigre, J.P.; Morand, J.C.; Tharaud, M. Pathologie des cultures florales et ornamentales. Lavoisier, Paris; 1987.

Boesewinkel, H.J. New or unusual reports of plant diseases and pests. II. Two species of powdery mildew on exotic rhododendrons in Edinburgh. Plant Pathology 30:119-120; 1981.

Braun, U. Descriptions of new species and combinations in Microsphaera and Erysiphe. Mycotaxon 14(1): 369-374; 1982.

Braun, U. A short survey of the genus Microsphaera in North America. Nova Hedwigia 39:211 -243; 1984.

Braun, U. A monograph of the Erysiphales(powdery mildews). Beihefte zur Nova Hedwigia 89:700pp; 1987.

Brooks, A.V.; Knights, I. From Wisley: Review of plant troubles. The Garden 109: 115-116; 1984.

Buczacki, S.; Harris, K. Collins guide to the pests, diseases and disorders of garden plants. Collins, London; 1981.

Butt, D.J. Epidemiology of powdery mildews. In Spencer, D.M. The powdery mildews. Academic Press: pp. 51-81; 1978.

Cochran, K.D.; Ellett, C.W. Evaluation of powdery mildew severity on deciduous azaleas at the Secrest Arboretum-1989. In: Ornamental Plants, a Summary of Research, 1990; Ohio State University Special Circular 135: 54-58; 1990.

Cox, K. A Plantsman's guide to rhododendrons. Ward Lock, London; 1989.

Cox, P.A. The cultivation of rhododendrons. Batsford, London; 1993.

Coyier, D.L.; Roane, M.K. (Eds) Compendium of rhododendron and azalea diseases. APS Press St Paul; 1986.

Evans, J.; Hutchison, D.; Cook, R.A.J. Rhododendron powdery mildew. The Garden (R.H.S.) 109: 406-407; 1984.

Heifer, S. Rhododendron powdery mildews. Rhododendrons with Camellias and Magnolias 44: 35-38; 1991.

Heifer, S. Rhododendron powdery mildews. Acta Horticulturae 364: 155-160; 1994.

Jenkyn, J.F.; Bainbridge, A. Biology and pathology of cereal powdery mildews. In Spencer, D.M. The powdery mildews. Academic Press: pp. 284-321 ; 1978.

Minch, F. More on mildew. J. Amer. Rhod. Soc.48:19; 1994.

Munro, J.M. Infection studies with powdery mildew from Rhododendron and Erysiphe cruciferarum. Transactions of the British Mycological Society 86: 686-687; 1986.

Nomura, Y. Two new powdery mildew fungi on Euonymus sieboldianus and Rhododendron macrosepalum. Transactions of the Mycological Society of Japan 25: 475-484; 1984.

Peries, O.S. Studies on strawberry mildew, caused by Sphaerotheca macularis (Walk ex Fries) Jaczewski. Annals of Applied Biology 50: 211-224; 1962.

Phillips, D.H.; Burdekin, D.A. Diseases of forest and ornamental trees. Macmillan London; 1982.

Pirone, P.P. Diseases & pests of ornamental plants. 5th Ed. John Wiley & Sons New York; 1978.

Schnathorst, W.C. Environmental relationships in the powdery mildews. Annual Review of Phytopathology 3: 343-366; 1965.

Watling, R. Rhododendron-mildews in Scotland.

Sydowia

38: 339-357; 1985.

Weiss, F. Index of plant diseases in the United States. Part II. Plant Disease Survey Special Publication; 1950.

* Name not registered.

Footnote

1

Recently a specimen of the

Oidium

type was received from Kentucky, USA.

Editor's Note: U.S. law prevents the use of any pesticide for a purpose that is not included on the label.