JARS v51n2 - Paths for the Informal Garden

Paths for the Informal Garden

Joe Parks

Dover, New Hampshire

It sounds like a dumb question with an obvious answer, but let me ask you, "On which would you be more inclined to dawdle and enjoy the surroundings, a winding mossy path or a straight paved one?" Clearly, paths set the mood and determine how we experience our surroundings. With just a soupcon of extra effort, your paths can set the mood of your garden and make it into something special. Let me give you a few suggestions how to achieve this.

In a previous article ("Secrets to Beautiful Rhododendron Garden Design," Fall 1996), I wrote about the importance of path layout in the garden. Equally, if not more important than the layout, is the nature of the path. Just as surely as the path serves as a guide, its nature will subtly influence how visitors view it.

My garden, for example, is mostly rhododendrons and the paths meander through them. Some paths are gravel, some are stone surrounded by moss, some are field stone and others have steps of railroad ties, etc. Beds of perennials are interspersed among the rhododendrons. Hopefully, there is always something of interest, something to intrigue the visitor and delight the senses throughout the year.

Path Width

It's one thing for a path to guide visitors through the garden but another for it to subtly slow them down and focus their attention. Here's where subtlety in path design comes into play. In addition to curves, vary the width of your paths. Like still pools along a babbling brook, occasional wider sections of path will encourage people to tarry.

Paths only a foot wide are walkable, but because plants eternally encroach, you would be wise to make none less than 2 feet. Four feet wide is the minimum width for walking two abreast comfortably. Five feet or more is necessary for even a small group of people to gather.

Steps

Steps should be thought of as a special facet of a path. They are particularly effective in slowing people down and emphasizing plantings. Even though steps are unnecessary in your garden, if at all possible, you should include some for variety. Each step should be 4 or more feet long, the tread 18 or more inches wide and the riser no more than 6 inches. Such steps will be safer and provide ample room for plants to overflow the ends. One important point, if you do build steps, set up a work route around them. If you've never tried it, I can tell you that trying to push a loaded wheelbarrow up steps is somewhere between totally frustrating and impossible.

Edges

The more informal a path, the more important that its edges be clearly defined. No one would confuse a brick path with your plantings, but a pine needle path that becomes a bit overgrown can be as hard to follow as a deer trail. If there can be any doubt, place some rocks or a low, unobtrusive fence along the edges. I bend straight branches (2- or 3-foot pieces of willow, arrow-wood, bamboo, etc.) into a "U" shape and stick the ends in the ground alongside paths. Overlapped they make an unobtrusive but very effective "fence."

|

|---|

Here an ill defined path encourages visitors to wander at will. This is to be avoided if you do not wish low growing plants to be stepped on. Author's garden. Photo by Christian C. Curless |

Safety

It is important to be safety conscious about your paths every step (pun intended) of the way. If your path causes people to take excessive care in walking, they'll pay that much less attention to your garden. Paths should be slightly above the surrounding soil so they will drain well. But paths or stepping stones raised much above the level of the surrounding soil, while charming, can be unsafe.

Materials

In paths, even more truly than in communications, "the medium is the message." Never forget that the materials you choose for your paths subtly create the image your visitors will have of the garden and will affect the mood with which they view it.

The variety of materials for building paths is almost endless: concrete, pavers, asphalt, brick, cut stone, field stone, gravel, wood, pine needles, mulch, grass, dirt, moss, etc. In deciding which to use, you'll need to consider these five points: 1) how you wish visitors to "see" your garden, 2) ease of construction, 3) terrain problems, 4) ease of maintenance, and 5) cost.

Grass, moss or dirt paths are the most natural appearing, not to mention inexpensive. All create a restful, casual mood, are lovely, blend well into the garden and, well kept, will be the envy of all who see them. They're perfect for an informal garden but in my experience are lots and lots of extra work.

Grass, I think, has the most problems, with moss in there neck and neck. Grass paths have to be kept mowed, trimmed and weeded (for easy mowing a grass path should be at least 4 feet wide). Grass grows poorly in the shade and creates real difficulty if some parts are shaded and others are sunny. Worst of all, grass spreads. Before you know it the grass in your path will be living - and well, too - amongst your choice plants.

Moss is particularly beautiful, creates a restful mood, is easy to establish and (if it likes the location) is fairly fast growing. From long experience I can tell you, though, traffic quickly damages, it needs much moisture and it loves to play "mine host" to every seed within 50 miles. Its best use is to soften the appearance of stepping stone paths.

|

|---|

Moss paths are particularly nice but do not stand up to foot traffic, require continuous moisture and attract weeds. Thus they require substantial maintenance. Author's garden. Photo by Joe Parks |

Dirt paths do look wonderfully informal. Certainly nothing is easier to make and the materials are inexpensively at hand. Lay it out, dig it, dampen it, tamp or roll it and you're done. In my experience, though, unless very well tamped and drained, the problems exceed the advantages: dirt paths require careful marking lest someone wander into a flower bed, they get muddy and they quickly become scruffy from invasions of grass and weeds.

Choose any of these three materials, maintain it well, and I promise you plenty of "ohs" and "ahs" - also plenty of maintenance. I'd rather spend my time with my plants.

|

|---|

Cut stone laid in moss make an elegant pathway. The moss softens the formal appearing stone while the stone protects the moss from damage. Author's garden. Photo by Joe Parks |

Concrete, pavers, asphalt, brick and square-laid cut stone are perfect in the proper surroundings, i.e., the more formal garden. They are almost indestructible, need little maintenance, are easy to walk on and provide easy work access. But they create an institutional air out of keeping with informality. And, too, there's something about a smooth paved surface that tends to make visitors walk faster and thus miss things you might wish them to see. If you do use any of these, be sure to vary the surface treatment and soften the edges with sprawling plants.

|

|---|

Here a path of cut stone guides the visitor through the pine needles. Informality is gained by varying the orientation of the stones and surrounding them with pine needles. Author's garden. Photo by Christian C. Curless |

I have found the best, most easily maintained choices for the informal garden path to be field stone, gravel, or mulch. Irregularly placed pavers or cut stone are also a good choice particularly if planted with a creeping ground cover such as moss or thyme between the stones - but be aware of the extra maintenance.

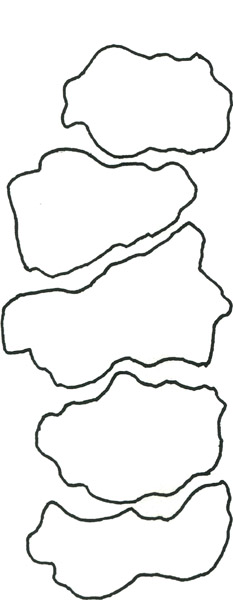

Stepping stones should be as large as can be easily handled. Anything less than 12 inches in the smallest dimension will be insecure and tend to make for uncomfortable walking. If you want a really elegant, informal path, use irregularly placed field stones and surround them with moss.

|

|---|

Field stone surrounded by haircap moss makes a lovely, informal pathway. Author's garden. Photo by Christian C. Curless |

I particularly like gravel paths because they are easily built, blend nicely into the garden, need little maintenance and, not to be forgotten, are economical. They do, however, take time to pack down and become easily walkable. I use ¼-inch or ⅜-inch bank run, washed gravel - larger sizes tend to be difficult to walk on. Gravel paths should preferably be at least 3 feet wide to allow for plants which inevitably root along the edges.

Next to dirt, wood chips and tan bark mulch are the most informal of all. They blend well with plantings, are easy to use and prevent mud. My experience, however, is that they take considerable time to pack down and become walkable, they attract weeds and they break down quickly, thus requiring extra maintenance. You may decide the ease of building and the informality worth the effort. Three feet wide should be the minimum for these too.

Construction

In building paths, the most important rule is: prepare an adequate base. Lack of a good base soon creates problems, with the possible exception of very heavy stones (and even they frost heave). From experience, I can tell you it's easier to do the job right in the first place

I dig down 6 to 10 inches for a gravel path and line the bottom with tar paper, plastic or horticultural cloth to stop roots. Mulch and dirt paths will last longer if done the same way.

To lay stones, I dig a 6- to 10-inch deep hole a bit larger than the stone and fill it almost full of pea gravel. I put the stone on top and shift it back and forth until it is level and securely in place. It is most important that the top of each stepping stone be parallel with the ground and with its neighbors. Forget this and you're likely to learn why it's so important to keep your insurance policy paid up. With brick or pavers a proper base is even more important because of the ease with which they shift and the difficulty of repairs.

Be aware that good drainage is also important. In some instances drainage pipe under the path may be necessary to prevent maintenance problems.

A sound foundation is particularly important for steps and bridges, as they can quickly become insecure from erosion and winter stress. It's even more important with very large units because their sheer weight may cause them to shift. I always use gravel or crushed stone to provide a solid, well drained base for steps. To secure railroad ties in place, I drive 60d (sixty penny) nails into the bottom and then force the nails into the ground.

|

|---|

Stepping stones should be as large as can be easily handled. |

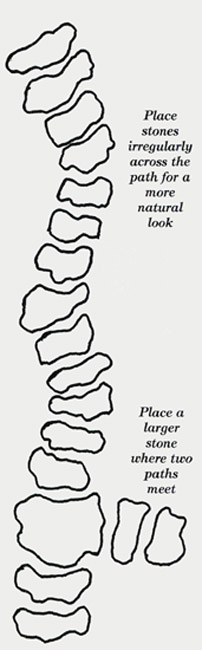

For stepping stones, assure a natural look by placing the individual stones irregularly in the path. Done properly this also helps assure easy walking. More importantly it provides a casual, natural look and reduces monotony. Lay stones so that their irregularities match, i.e., a bulge on one matches the indentation on the one next to it, a wedge shape is matched by another, etc. To achieve this, I first lay the stones out beside the path and move them around till they match best.

|

|---|

Place stones so that a bulge in one matches an indentation in another. |

Stones laid lengthwise across a path tend to fool the eye and make a path seem longer than if they are laid lengthwise end to end. How far apart to place stepping stones is an eternal debate. Try walking the proposed path and then lay the stones a bit more closely together than are your footsteps.

Every single one of us loves to have visitors enjoy our garden. Paths are a major key to that enjoyment. Paths can create a mood of anticipation and mystery and, yes, illusion that will take your garden, large or small, out of the ordinary and make it something special. Paths are necessary anyway, so why not build them so that they make your garden into that something special. It's so easy to do, you'll always wonder why you didn't do it sooner.

Auxiliary Reading

Space and Illusion in the Japanese Garden

by Teijo ltoh (Weatherhill/ Tankosha).

Garden Design Ideas, The Best of Fine Gardening

(Taunton Press).

Garden Paths

by Gordon Hayward (Camden House Publishing).

Joe Parks lives in New Hampshire where he has a 6-acre rhododendron garden and a 70-acre tree farm and where he hybridizes rhododendrons. He has been a newspaper garden columnist and has written for such magazines as Fine Gardening. Joe is also the immediate past president of the Massachusetts Chapter.