JARS v54n3 - Sikkim 2000 - The Ascent to Yamthung And the Search for Rhododendron wightii

Sikkim 2000 - The Ascent to Yamthung

And the Search for Rhododendron wightii

Clive Justice

Vancouver, British Columbia

Canada

There were fourteen of us who made the trip to this tiny area that pokes up between Nepal and the even smaller kingdom of Bhutan in the eastern Himalayas, where 152 years ago J. D. Hooker found the rhododendrons species that became the links to the great garden hybrids that came to grace the gardens in England, Scotland, Ireland, Denmark, Holland and Germany and now the gardens on the Pacific Coast of North America from San Francisco to the San Juan's and on to San Joseph Bay. The rhododendron species in particular that were our quest, like griffithianum , campanulatum and campylocarpum , were the ones that gave us the Loderis, the Exbury Caritas, some of the Hackman hybrids, the Pacific Northwest Wallopers, and their many hybrid derivatives. We got to see these three species of rhodos plus nine others in various habitats. They occurred as individual roadside specimens, blankets on hillsides, mixed undergrowth beneath silver fir and Himalayan hemlock, forests of a single species, and epiphytes on broken stumps. Eight of the twelve were in some stage of blooming.

The Sikkim 2000 Group consisted of Britt Smith, Fred Whitney, Rex Smith, Jeanine Smith, Ann Dona, Lawrence Dona, Paul Anderson, Bruce Cobbledick, Karen Swensen, Beth Harris, George Lewis, Verna Lewis, Elizabeth Harris, and myself.

Britt Smith of Kent, Washington, and the writer go back to 1974 when he led the first ARS trek into southwestern Sikkim that started along the Sikkim-West Bengal and Nepal borders beginning where all the borders meet on 12,000-foot (3600 m) Mount Sandakpuh. This and the area north of it, we left to the twenty-three member Danish rhododendron group that had preceded us to Sikkim and to the serious fit and young mountaineers and trekkers; for it is the way up to the base of Kanchenjunga. We learned later that a group of arrogant Austrian climbers had generously paid the Indian government in New Delhi to gain permission to climb to the top of this sacred mountain ignoring the long held practice of the Lepcha people not to violate the mountain's spirits by stopping short of the summit.

After an all night train ride from Calcutta that is best forgotten, we arrived in Siliguri and into the safe and competent hands of Sailesh Pradhan (Keshab's son) and his crew of guides and check point facilitators from Sikkim Adventure, Botanical Tours and Treks. (Be warned don't go to Sikkim unless you are under their care and guidance.) After Sunday brunch at a local hotel, we boarded our bus with baggage atop and began the drive up to Darjeeling. It would give all twelve tour members, who had not ever been to India, a chance to gain experience with the mountain roads that were to come. It was raining and foggy as we started our winding ascent of the roadway that follows the famous narrow gauge railway line up to Goom and Darjeeling. We had not gone far when our bus rounded a curve on a steep climb to face a large heavy truck sliding sideways towards us. Fortunately the truck found traction and drove into the hillside while we slipped around on the outside edge (India drives on the left.) Had the truck continued to slide it would have pushed the bus over the edge ending up more than several hundred feet below and you would not be reading this writer's report. After that episode there was an immediate and sustained faith and trust in the abilities and actions of our driver by all of us. We passed through Goom where the railway and the road come together along the street, and as we neared the outskirts of Darjeeling there it was on the steep bank high above us just as we had seen it 26 years earlier among the ferns, agapetes and vacciniums - a cluster of white trumpets, our first rhododendron, unmistakably dalhousiae . Joseph Hooker had named it in 1848 for Lady Dalhousie, the consort of the then British Governor General of India, and aptly too, for it is a regal rhodo.

Sailesh had chosen a new hotel for us, the Cedar Hill, perhaps named for the common name of the Cryptomeria japonica trees, planted in the 1920s and dotted everywhere singly and in groves in this bourgeoning city. Access to it is up a series of switchbacks that appear too steep for any vehicle to traverse but our bus groaning and grinding made it to the hotel gate. All rooms face north and in the morning the rising sun parted the mist curtain to present us with a half hour of Himalayan mountain splendour. On the writer's two previous visits to Darjeeling, the gleaming white line of jagged peaks against an ice blue sky was never like this. We were to experience a similar early morning mountain panorama when the curtain of mist parted at Gangtok. Darjeeling is a city of rock walls where Erigeron bellidioides has taken over the crevices and acting like an epiphyte forms patches of tiny white daisies that enhance these walls which are everywhere. It's as if the English field daisy has taken possession of these vertical surfaces, finding there were no fields in Darjeeling to carpet. In the grove of Cryptomeria midway up to the hotel there was a large Rhododendron arboreum in full bloom. These plants are usually only sparsely covered with bloom, but this one was an exception with a full fall of flowers. We saw many others but didn't see a similar full display of flowers on Rhododendron arboreum until we visited the lovely monastery at Lachung and saw the 40-foot (12 m) tower of deep rich red flowers over the top of the monastery's woodshed. More about this monastery to come.

|

|---|

R. griffithianum, one of Hooker's 'supers' in Madan Tamang's garden in Darjeeling. Photo by Clive Justice |

In the morning of the one full day between the two nights' stay in Darjeeling, our group went to the hillside garden of Madan Tamang. His garden is mainly of Himalayan plants. Several maples, Acer campbellii (I believe) were just leafing out with their emerging foliage glistening bronze in the morning sun. There were many newly planted big leaved rhododendrons but the feature of the garden was a stand in full flower of one of JD's five "supers" above the terrace beside Madan's new stone house. Named for the superintendent of Calcutta Botanic Garden, Rhododendron griffithianum blooms like a camellia, with its scattered large white, wide open, wavy edged flowers and red new growth commanding attention. Rhododendron griffithianum, this "super" of them all, we were to see several more times as a Sikkim roadside shrub, almost always as a handsome stand-alone. We had a chance for an aerial photograph of the famous mini train from the front terrace, as it tooted along the tracks beside the roadway below. Madan's garden is located on one side of a steep draw between an upper road, the preferred route out of town, and a lower main road that follows the rail line into town. There must be 200 to 300 feet (60 to 90 m) of drop in the garden between the two roads that finally join some 15 kilometers away.

|

|---|

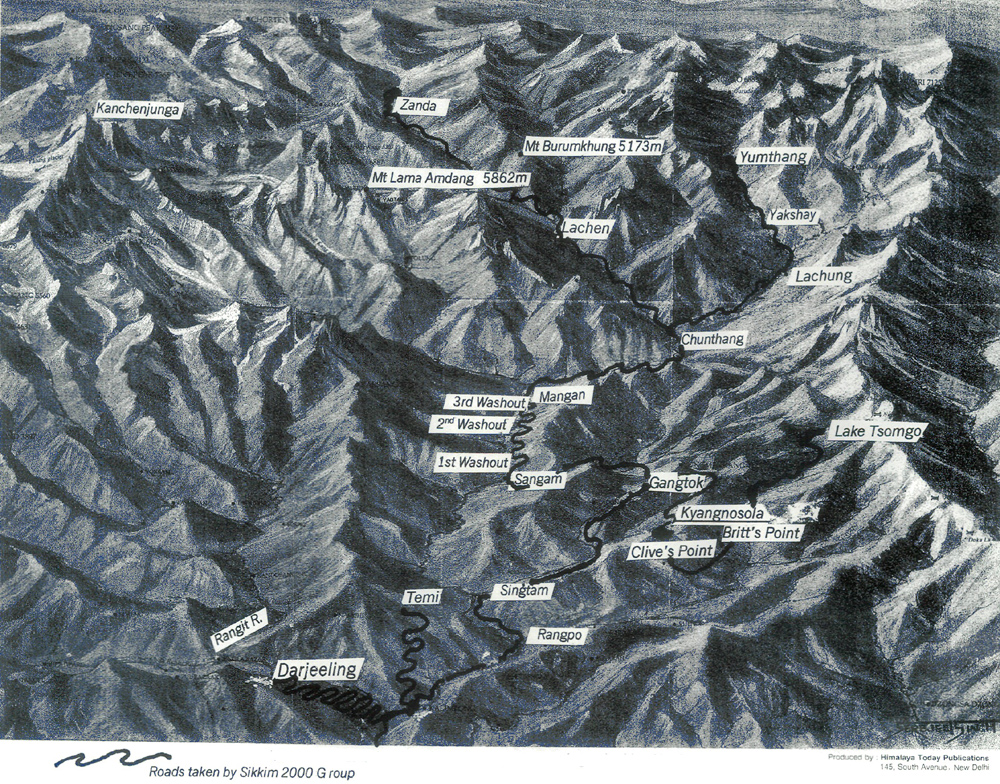

In the morning we were off by 9 to Sikkim. At Coom we split off from the road to Siliguri and started a winding descent down into the west to east Rangit River valley. We enjoyed views north into the mountain slopes of Sikkim as we wound our way back and forth around the natural spurs and draws of the mountainside to the river level. We crossed the Rangit, turned east and followed beside it on the north side crossing over to the south side of the Teesta beyond its confluence with the Rangit and drove up beside the Teesta to Rangpo. We crossed the Rangpo River and entered Sikkim (see map). Sailesh had preceded us and so we had only a short wait at the check point while border officials processed the paper work. It wasn't long after that we got our first flat tire on one of the duals on the bus. The stop for the quick change by the driver and his helper gave us an opportunity to stretch and observe the Teesta River flowing due south at this point and admire many roadside plantings of Bougainvilleas that beautify portions of this part of the national highway up to Sikkim's capital, Gangtok. The roadway up is developed on both sides far down below the town, a fivefold increase from ten years ago. You used to be able to look out over the valley to Kanchenjunga from the roadway, but now all the open spaces are filled in with houses, shops, and government offices.

|

|---|

View from Altitude of 40 Kilometres North Above Bagdoogra, looking North Photo by Paul Anderson |

The bus pulled up in front of the Hotel Tibet just off the roundabout in Gangtok at 3 p.m. Lunch was announced for 4:30 and at 7:30 we were to meet the Danish group at a reception in our hotel basement. The Danes had come across from Yaksam above Pemayangtse in Sikkim's West Forest District, traveling up and down across the South District passing by the Temi tea estate to Gangtok which is in Sikkim's East Forest District. In the rest of Sikkim, 60 percent of the area is in the North District including 28,000-foot (8598 m) Kanchenjunga on the Nepal border just north of the West District's northerly border. The reception and excellent buffet was hosted by ARS Gold Medalist Keshab Pradhan, president of the J. D. Hooker Chapter of the ARS, and Mrs. Pradhan (Shanti), jointly with ARS Gold Medalist Sonam Lachungpa who is in charge of the development of Sikkim's Alpine Sanctuaries and Rhododendron Protected Areas along with the Rhododendron Test Garden and Zoological Gardens nearby Gangtok. The Minister and Deputy Minister of Sikkim Tourism were also there to welcome the two groups. Our group were the gregarious ones, meeting and chatting with the quieter 32-member Danish group. We were to meet them again twice more.

We spent the next day in Gangtok visiting the flower show where hybrid Cymbidium orchids (many from Sonam's nursery) and potted Imantophyllum miniata or clivia with their scarlet trumpets were the main exhibits. Then on to the Tibetan Buddhist Do-Drul Chorten or Stupa, and monastery, the nearby museum of Tibetan Buddhist artifacts at the Institute of Tibetology and back up to Gangtok and the handicrafts Factory and Emporium. We watched the handloom weavers of carpets and the wood workers sawing out intricate patterns for the folding coffee tables called "choktse" that are a feature along with the all-wool rugs and other products that they manufacture for sale. Britt Smith, our expert on Sikkim (this was his seventh visit) told us that prior to 1975 the handicrafts factory was initiated by Namgyel, Hope Cooke, the American wife of the Chogyal, as a way to employ the young Tibetan refugees and preserve the local Lepcha and Bhutea handicraft patterns and motifs through production of saleable handicraft items.

We were all eager to get up to Lachen and see the acres of rhododendrons in this upper portion of the great Teesta River valley. It had only recently been open to tourism. We would be the first guests in a newly completed ten-room hotel in the village. The paperwork was complete and all commanding officers had been advised of our move so that when the check point guards (who can't read) phone up their COs, they would know to allow us through, but there was a slight hitch. It seems the recent heavy rains in the north had caused major washouts in three places. We drove to the first washout, engaged some locals to carry our baggage across temporary log bridges and rocks in the roaring stream, and then walked or caught a lift in army trucks and the other vehicles trapped between the washouts to ferry the baggage and travelers back and forth between the washouts. There was only one vehicle, an army two-ton dump truck, to ferry the baggage for the six kilometer leg between the second and third washout so only the two over 80, Elizabeth Harris and Britt, rode in the front seat of the truck. The rest of us started to walk, while our baggage was being loaded. The lorry driver was only supposed to carry the baggage and handlers in the back of the truck, but as soon as he got around the corner out of sight of his officer, he started picking all of us up.

|

|---|

The Sikkim 2000 Group make it across the log bridge at the second washout on the way up into North Sikkim. Photo by Clice Justice |

Crossing this last washout involved a climb up among boulders to a temporary wooden bridge across the raging torrent of water and then down a very steep trail to the road on the other side where a contingent of army trucks waited along with our three jeeps from Chumthang hired to take us onward. All our baggage had arrived safely and was wrapped in tarps and strapped to the top carriers on the jeeps and we were off to Chumthang. We reached it just as it was getting dark and stopped for drinks and chips at the local hotel. When we got going again we were hit by such a heavy downpour our jeeps had to stop and wait out the worst of it. The results of the storm appeared on the road: torrents of water fell, bringing down rocks and boulders that blocked our route. The assistant drivers ran up ahead, removing just enough rocks so that the jeep could maneuver through. Again luck was with us when the third jeep made it through just as a large rock came crashing down on the road behind it. A half hour or so later we pulled up at a dimly lit major bridge checkpoint. The driver cut the motor and we climbed out to stretch. After a minute or so we suddenly realized there were no jeeps following behind. No lights, no motors, just blackness and dead silence.

It was an eerie feeling not to have the others with us, as it was pitch black and we suddenly felt awful lonely beside the a flickering flame from a can of oil beside the shadowy dark uniformed figures at the checkpoint. We had no way of knowing that the last jeep had a flat tire and the second jeep had luckily seen it and had gone back to help with the tire change. All we could do was wait hoping nothing had happened. Then after what seemed an eternity they suddenly appeared rounding the turn that had cut off any view of the road behind. What a relief to know everyone was still with us and not somewhere in the Teesta River a thousand feet or so below. On our return in daylight we saw how awesomely high the two-beam Bailey Bridge was above the river.

We arrived at the street side gate of our Lachen hotel. Paul Anderson, Bruce Cobbledick, and I drew the bridal suite with a magnificent floral curtained five bay window projection with sectional sofa all around it. I got the double bed, Paul the cot and Bruce the floor. All the rooms had the most modern electric light fixtures, and in the bathrooms there were tanks for heating water but there was no power to them, so candles for light and cold water for washing had to do. A late supper was served in the main lounge around a coffee table with light from a Butane fed mantle light with heat from the fireplace whose 30"x 4" logs stuck out on the hearth and had to be pushed into the fire to keep it burning. The length of the firewood is not geared to the fire but to what is a convenient length to carry in and piled atop tapered backpack baskets, the common carryall in Sikkim.

The day had finally arrived for some serious rhododendron viewing and botanizing and we were not disappointed. First, though, we had to wait for the bulldozer to come down to clear away a rock fall from the road to the north to the Chimakaru Rhododendron Sanctuary. In the meantime we visited the Lachen Monastery area. It was rather run down and the Compa was closed. A little below the monastery we came on a sopping wet hillside of rhododendrons. As one of our group's rhodo experts, Fred Whitney went wild. It was his first time in Sikkim and so he had probably never seen a hillside, 60 or so acres, covered with them. There must have been six to ten different species, most were not in bloom yet but Rhododendron ciliatum was out and lovely. It and the others grow on hummocks among hillside bogs. The whole hillside is a bog.

Along the roadside at the foot of this hillside of rhodos were shrubs with glistening bronze new foliage that was just unfolding and providing a pleasant contrast with the green of the rhodos. They turned out to be Acer sikkimensis. We were on the west side of the river high up above in the Abies and hemlock forests, and we looked across to forested slopes, in shade for the most part. Wherever there were areas of grass beside the road and cleared areas between rocks beside streams that stretched up into the trees there were patches and clumps of the lovely mauve toothed primula, Primula denticulata. The flowers have a white sclera around a purple eye and are arranged in a tight ball on a short stem. We were to see this bright, delightful plant many times more over the next few days.

|

|---|

Roadside Primula denticulata above the Teesta River form a crowd watching the clouds lift from Mt. Burumkhung, 5173 m, up the road from Lachen. Photo by Clive Justice |

After the bulldozer cleared the road, we gradually wound down out of the forest to the river and it wasn't long before we came on a terrace area in the curve of the river that was covered with drifts of rhododendrons. There were many meter high Rhododendron thomsonii plants scattered about, many in bloom with pink, red, green and off-white calyxes on light red, arterial blood and veinous blood coloured flowers. Fred and Bruce, the seed collectors helped by the Dona's, Lawrence and Ann, quickly got to work. The photographers, George and Verna Lewis, took on the scenery, Jeanine Smith with spotter and recorder husband Rex and Paul and Karen Swenson took on close ups of the floral variations while Beth Harris and her mother, Elizabeth, and the other Smith, Britt, sat by the roadside and watched in wonder. The Daphne, Daphne bholuha var. gracilis was common among the rhodos with its pink clusters of flowers along bare stems. Jeanine vowed she'd have it in her garden. The open grassy areas and banks had patches of the balls of flowers of Primula denticulata. George found a large mauve Rhododendron campanulatum in full bloom. There seemed to be fewer if any R. arboreum at this dryer location than there had been back at the hillside bog where Fred had found some in bloom.

We had lunch at a hill top further on where the Teesta turns to the northeast and on up to the Chinese border. On the last bit of the trip up we were on the east side of the very narrow gorge of the river and you could see across to a forested wall. The whole understory was rhododendron with the sun reflected off the leaves. It looked as if they were covered with lights. We had passed a village on our way up across the road from an Indian Army tank regiment Camp. They had a figure of a tank outlined in white painted on rocks on a slope high above the camp, and nearby climbing up the slope was a line of poles each flying a row of prayer flags. The constant wind makes sure that prayers are always being sent to the heavens. Across the road below the houses that lined the road was an extensive patchwork of stone and wire fenced potato, barley and millet fields. Many villagers were hard at work in some of the fields with a hand drawn wooden plow furrowing and hilling and then planting the hill with seed potatoes. It's hard to know but we think the village is called Zanak or maybe Yangdi. At a village further down, the rocky fenced fields were strictly pasture for yaks. There seemed to be none of these black bovine hairy horned beasts around, so assumed they had been taken up to the higher pastures to catch the first flush of growth after snow melt. We arrived back at our chalet just before dark. It had been a great day for rhododendrons.

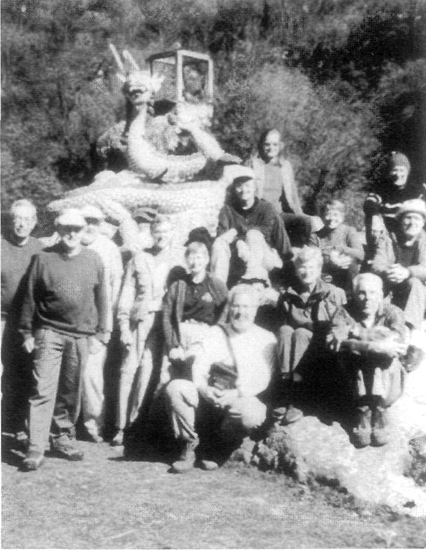

May Day morning found us packed and ready to go down to the Chumthang, (some maps show it as Chunthang) rest house for lunch with the Danes and to change places with them. They had been up at Yakshay lodge above Lachung where we would be going. After a fine lunch the Danes packed up and took off up to Lachen. We loaded the jeeps that had brought the Danes down and headed up to Lachung. It's Sonam Lachungpa's home village and has one of the most scenic and dramatic approaches. Lachung has grown in the past nine years. There's now a six storey tower hotel and a number of new guest houses. We passed them all, continuing on through a large army camp with its inevitable check point. Then on up to the Dragon-on-the-rock that identifies Yakshay Lodge. While Jeanine and Rex drew the honeymoon cottage just past the collapsed cook house and staff quarters and the rest shared rooms in the bungalow, Paul, Bruce and I got the room in the lodge off the kitchen. It had a sloping floor with holes and a barely attached toilet.

|

|---|

The Sikkim 2000 Group at Yakshay Lodge, Dragon-on-the-rock. Photo courtesy of Fred Whitney |

Features of the lodge were two large octagon windows with coloured glass panes and several windows that opened but wouldn't close. Settlement had skewed the frame out of square just enough to prevent closure so it was drafty. The piece de resistance, however, was the pot belly stove. It had been modified by a crown of two wheel rims and strap iron supports to help hold the body from falling completely apart. It took close to an hour to get it going and plugging holes so it would draw and not smoke. Britt vowed he would raise the necessary funds to replace it with a new stove. The problem, however, is much more than a new stove as the whole lodge desperately needs replacement. The lack of any maintenance or repairs over the years has resulted in a structure that is quite unsafe.

The grounds and surroundings of Yakshay make up for all the building faults. Which goes to prove the old adage that gardens improve with age while buildings fall into decay. Natural drifts and clumps of rhododendrons and other shrubs fan out on each side of the lodge and cottage, backed up by a forested hillside of Abies, hemlock and larch with an understory of rhododendrons and deciduous shrubs like Daphne, Lyonii, Edgeworthia and Viburnum. The driveway curves through an open field in front contained at its edges with a rock wall. Several young yaks grazed in the field prompting a photograph titled landscape with yaks. There is a stream running through the field bordered with drifts of white Rhododendron ciliatum. The great boulder with the dragon on top is right out in front of the lodge forming a centre piece to the landscape. The garden has some great secrets. We weren't there long enough to find them all but we did find one.

Hidden behind an even larger boulder off to the side of the field there is a collection of the native cobra-lilies or pitcher plants of genus Arisaema. Sikkim boasts sixteen species of these bizarre plants. I'd bet there was a dozen of the sixteen behind that huge rock dropped there by some passing past glacier. The most spectacular one is the coal black Arisaema griffithii. The black and striped hoods and trillium-like leaves sprung up magically with more and more appearing each day of our stay. Each hood has a long thread or fishing line (botanists call it a spadix) that dangles out to the ground, so that ants can travel up it and down into the spathe to the tiny flowers to fertilize them. The ends plants will go to have sex!

Several of Sikkim's official tree, Rhododendron niveum, were in bloom on the grounds. One in particular, paired with the Lachung arboreum, Sonam rated the "the best form yet seen." They both stood against the faded ochre wall of the lodge beside the kitchen entry. It was a nice background to the dull purple of the niveum blossoms which do brighten when the sun shines through them. Bruce and Paul found R. cinnabarinum, with small flowers growing as epiphytes on top of the boulders surrounded by shrubs in the garden along with a clump of the dwarf species R. glaucophyllum, with rose flowers displayed up against a grey granite of one of these rocks.

We were wakened with a cup of tea and after a breakfast of porridge and scrambled powdered eggs, we loaded up for the trip up to Yumthang. The road paving crews were out just up the road from the lodge, with their barrels of tar and shallow pans over fires where they heat the tar and gravel mix to place it by wheelbarrow on the road. The only power equipment they use is an old fashioned steam roller that smooths out and compacts the hot tar and gravel mix and bonds it to the old road surface. George Lewis had gone out earlier in the morning to record this hand paving process. We came on several patches of melting snow and swaths where snow avalanches had ripped through the smooth cream coloured, multi-stemmed R. thomsonii forests of the Shingba Rhododendron Sanctuary that had been fenced in 1991.

The avalanches had torn out all the fencing at this lower end of the sanctuary. Things got better as we drove up into and through a forest of large old fir and hemlock with an understory of rhododendrons stretching up on one side of the road, so you saw under the rhodos and down to the river on the other side of the road, where you looked over the tops of the rhodos. A new large leaved species would appear and then be replaced with another, then another, while the rhodos like campylocarpum, campanulatum and thomsonii continued as an understory for the big leaved boys, thickets of them waxing and waning as we proceed along the road. Just outside the top edge of the forest is the Yumthang rest house, now an army hostel and school. It looks out over a wide plateau surrounded by a wall of mountains with heights in the 19,000-foot (5,800 m) range. Yumthang plateau is at 12,000 feet.

On the open slopes beside and behind the rest house was a hillside of Rhododendron campylocarpum not yet in bloom, and in the grassy areas between there were the balls of mauve edged, white inside flowers of Primula denticulata. Scattered about among the primulas were a few yellow flowers and fuzzy little feather like leaves of Potentilla peduncularis. I think the yaks graze on the potentilla but not the primulas but both keep a low profile in the grass. After the seed collectors and photographers had their fill of the campylocarpum hillside we loaded up and started back. Most of us chose to walk so we could see the succession of rhodos. However, when we stopped and started walking we had missed R. wightii, picking up on R. hodgsonii, R. grande, R. campanulatum ssp. aeruginosum and R. x decipiens. The hodgsonii was most common, and though we knew the others were there we didn't find them. A few of the hodgsonii were just beginning to flower. Rhododendron hodgsonii is a strong red. Bruce found R. pumilum growing as an epiphyte; as he's an orchid man it was only expected of him.

When the forest ended, we got back into the jeeps and moved further down to the thomsonii forest area that is just above the lodge. In the undamaged part missed by the avalanche Sailesh remembered where a white flowered thomsonii was, so he and a few others went down near the river to find it. They did, but found no seed and few flowers. When we got back to the lodge and had our lunch it irked several like Fred and Bruce that they hadn't found R. wightii so they commandeered one of the jeeps and took off back up to Yamthung to find it. They found one with a truss just about to open so they brought it back to the lodge.

Fred and Bruce extracted the pollen from each of the unopened buds with the aid of several flashlights held by others of the group as it was dark when they got back. Rhododendron wightii is the least known of Hooker's "supers." It was named by J.D. for the Superintendent of the Madras Botanic Gardens, Dr. R. Wight. Sonam says its large flowers can be cream, deep yellow or white, with or without spotting or a crimson blotch, but the large leaves with cinnamon-brown under distinguish it from other species. It has been used little in hybridizing. 'Polar Bear' is one of very few hybrids of R. wightii. Maybe Fred's and Bruce's wightii pollen will produce a few more that will be worthy. Paul Anderson in his quiet way was thinking seriously of getting rid of his 'Polar Bear' as it was getting out of hand and too big for his Santa Rosa garden.

On our last day at Yakshay we went down and across to the Lachung Monastery across the river from the village. Then we continued on up to a viewpoint very close to Sikkim's eastern boundary with Tibet-China. It gave a panorama view up and down the Yumthang Valley and west across to the wall of mountains between the Yumthang and the Teesta. There was a white fall of water on this wall that fell a thousand feet. At the monastery there is also a viewpoint. It was reached by a path and steps beside an orchard of apples in flower (the Lachung area is also known as apple valley). On the viewpoint there is a mini arboretum of Himalayan larch, Pinus gerardiana and P. roxburghii Betula utilis, the magnolia-like fall flowering Michelia kisopa along with several small trees just leafing out.

I took several photographs and returned back down to the front of the Monastery, careful to complete my clockwise circuit of the Gompa. The old head Llama was supervising the planting of the garden that is along the front on each side of the main steps up into the Gompa. They were planting big plump dahlia tubers between the roses and lupins already in place. Britt arrived on the scene and he and the old Llama recognized each other from a time some years before when he and Britt met on an earlier visit. Old guys don't go in for hugging much but this time they did it. It was a touching scene and a surprise for both of them.

It was clear and sunny for the early start of the six hour trip to Gangtok. No washouts to hinder our progress this time. I was selfish and made the jeep stop several times on the way down to Chumthang, the first leg, so I could photograph the sun through the new leaves on the poplars and the golds and greens of trees leafing out on the sunlit forested slopes across the river. For me personally it was an unexpected highlight of the trip to see the diverse Himalayan mixed forest bursting into life. We arrived back at the Tibet Hotel to beds, hot water and laundry service. Our third meeting with the Danish group was a Chinese buffet fine food with conversation comparing our Lachen and Yakshay experiences.

|

|---|

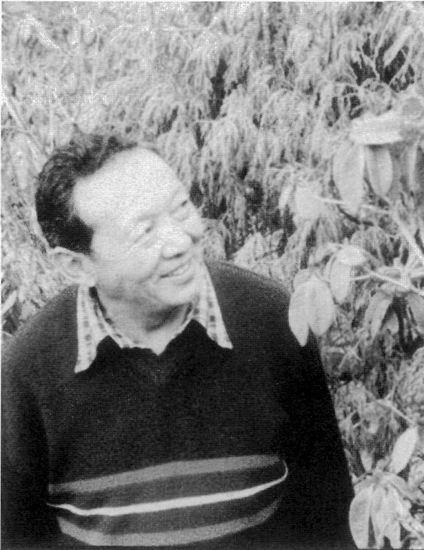

Sonam Lachungpa with his discovery R. sikkimensis, one of the rhododendrons growing on Britt's Point in the Kyangnosola Alpine Sanctuary. Photo by Fred Whitney |

We took the occasion to introduce everyone to "Jack Daniels," the first honourary member of the J.D. Hooker Chapter (having gained that honour for the succor provided on Sandakpuh in 1974), and to have all present sign a reprint copy of J.D. Hooker's 1848 Himalayan Journals that the writer took with him on the 1974 trek, adding to the signatures of all those who had that Sikkim adventure twenty-six years ago. A social note: beside our fourteen-strong Sikkim 2000 Group and the twenty-three member Danish Group, in attendance were President Keshab Pradhan and Shanti Pradhan; Sonam Lachungpa, Conservator of Forests, and his daughter; the late Chief Forester and now Advisor to Sikkim Tourism, Mr. P. K. Basnett; the present Chief Forester, Britt's friend Tashi Densapa from Sikkim Tourism; staff members from Sikkim Tourism; and Sikkim Adventure President Sailesh Pradhan and his several assistants.

Our round of official recognition for Sikkim 2000 now began. First there was the trip up to the Chhangu and the Kyangnosola Alpine Plant Sanctuary east of Gangtok, the site of Britt's Point and Tse Ten Tashi Cave. Sonam and his crew had constructed a rock paved path from the style over the roadside sanctuary fence and built several runs of stone steps to a path along a slope that traversed a forest of Rhododendron thomsonii with brown stemmed birch scattered through, not yet in leaf. It was a hard climb and I hung back from the rest sitting on my shooting stick as an excuse to take pictures at various places while I rested. I finally caught up with the assembled group on Britt's Point. After a group picture the group moved on. Sonam remained behind to point out the R. sikkimensis that is one of the features of Britt's Point. Then he and I followed on to an area a little lower that overlooked Tse Ten Tashi Cave. All were assembled as Keshab stepped up to me and declared the ground on which we all stood to be Clive's Point.

I had no idea that this honour of a small bit of Sikkim was to be mine. I noticed that there was a Rhododendron thompsonii with more than the usual amount of bloom occupying a prominent position on what is now Clive's Point. I'd never declared openly any preference for a species so no on knew that thomsonii was the one I favoured next to griffithianum. Bruce Cobbledick got out his GPS locator to read the coordinates of Clive's Point; they are N27-22.595' Lat. x E088- 43.483' Long. A position directly opposite on this side of the globe would be a spot in the Gulf of Mexico due south of Mobile, Alabama. So now there is Britt's Point for the United States and Clive's Point for Canada, a North American presence in the Kyangnosola Alpine Plant Sanctuary .

We continued on up to Lake Tsomogo where Tourism Sikkim has just completed a modern cafeteria chalet with detached toilet facilities on a promontory between lake and valley.

On our return to Gangtok we left the sunshine at Lake Tsomogo at 12,280 feet (3,780 m) and wound down through thick clouds that burst kilometers from the city, and when we passed out of the rain we came into sunshine approaching Gangtok. The name Gangtok means "top of the hill." It is at 6,080 feet (1,870 m) altitude. We had descended almost two kilometers in the thirty-eight kilometers distance from Tsomogo to Gangtok.

May 6th was the day set aside to honour the Sikkim 2000 Group. We were bussed up to the site of the Rhododendron Test Garden where a hillside is being converted into a rhododendron garden. It is and will be shaded by some existing tall Michelia trees and many newly planted young Michelia. I never found out whether these magnolia-like trees were the spring blooming M. doltsopa or the fall blooming M. kisopa, the latter most likely with the smaller cream flowers, as it is a Sikkim native and the other is found only in Nepal, I believe. The test garden is Sonam's work in progress but already there is the Rhododendron dalhousiae he planted way up at the top. The clusters of three flowers shine like beacons from the ends of many vine-like branches that tumble and hang out over rock ledges and out of crevices in the rocks beside the waterfall that feeds a stream winding down through the garden. That dalhousiae description should make Reginald Farrer turn over in his grave.

A great white tent was set up near the Test Garden entrance. It was an army cargo parachute and made a great pyramidal shaped shelter. There were chairs all in a circle all around with tables of tea and refreshments in the centre. In my 1991 report I had suggested that every visitor to Sikkim should plant a tree. So now it was our turn for each of us to do just that. First, however, were a welcoming by J.D. Hooker Chapter President Keshab Pradhan, introduction of the Minister of Forests, and our Britt Smith who told the story of how he and we came to be there. Britt's Sikkim story is in the spring 1999 issue of the ARS Journal. After we each signed the tree planting registry book, we each took a tree up to specially prepared holes where the gardeners helped us by bringing water to the trees we planted, as Keshab and the television cameraman recorded each tree planting. The trees weren't your usual tree seedlings but 5-gallon size bare root Rhododendron arboreum. If you wished to plant another you could, so I planted a tree fern for Wanda, probably the native Cyathea spinulosa. Then after a tour up through the garden to a gazebo or ting for a close-in view of the waterfall and the dalhousiae, we returned down through the garden to the tent and sat down to be served tea. Britt and I got to cut the cake specially decorated to commemorate the event.

The test garden continues down on the other side of the road as a memorial forest with sections planted by various schools, religious groups, and service clubs as a memorial or honouring one of their members. A sign posted along the road shows where the trees are that each group has planted. I gave some seed of Rhododendron macrophyllum and Mahonia nervosa to Sonam so that he can create a small Pacific Northwest area in the test garden with Washington's state flower and Oregon grape. British Columbia is represented because the Mahonia seed was collected on one of the Gulf Islands while Mr. Menzies' rhododendron seed came from the Upper Skagit River area of the Canadian Cascade Mountains.

Sonam then took us along to his other great project, the Zoological Gardens where animals like the red panda (Sikkim's state animal), the snow leopard, and the small Sikkim deer are each kept separately in 2-acre or more fenced regenerating forest and cane-breaks within the fenced gardens area. In 1991 when I saw the zoo site it had just been fenced and looked then like a Pacific Northwest clear cut logged area. The succeeding nine years has seen it become a dense thick and beautiful protected park forest.

Our social round continued with our dinner at the Pradhans' lovely house and garden. Keshab and Shanti and son Sailesh and his wife entertained our group with a fine Indian style buffet. When we arrived it was raining heavily but it cleared and soon after we finished eating so were able to tour their beautiful hillside garden and orchi

Keshab and Shanti's home has many kinds of Sikkim woods in it. Most unusual is the living room floor which consists of highly polished round tree trunk sections set in a dark terrazzo matrix. It was unusual and beautiful.

Our last full day was a bus trip to Temi Tea Estates in Sikkim's South District. It's squeezed in between the West District and the East District and North District so in terms of location it's in the middle of Sikkim. Relatively good roads made the trip down and over uneventful. There was a power outage so the whole fermenting, drying, rolling, shaking and sifting processes of making tea had to be explained as a dry run at each of the special machines involved. Our explainer was Sailesh Pradhan and he knew the process better than anyone, for it was the first industry his father Keshab had set up after his return from Yale where he'd taken his master's degree in forestry. When working they produce a fine tea. It brews up much darker than Darjeeling as it is an Assam variety. Germany used to take all the supply but now it is auctioned in the international market. Many of us bought several yellow boxes of Temi Tea.

Our last Sikkim 2000 social function was supper at the Lachungpa's hillside home garden and orchid nursery the evening of our return from our trip to Temi Tea Estates. We drove up to Sonam's about an hour before it got dark, so were able to tour his garden and orchid houses. One of Sonam's two daughters (I was smitten and wished I was 50 years younger) explained the tissue culturing she does of her dad's crosses to several of the group, who hadn't realized that the cloning of plants had begun more than 60 years ago. The Lachungpa's treated us to a traditional Sikkim meal with millet beer in traditional tall wooden mugs.

The hospitality of Sonam and his family, and of the Pradhans the day previous, will long remain the treasured remembrances of our Sikkim 2000 adventure experience. Thank you, Britt, for getting Sikkim 2000 up and going. Thank you, Beth at Huntington Travel, for getting us there and back on Thai. Thank you, Sailesh, for taking such good care of us and your attention to our needs. Many of us Sikkim 2000'ers will probably never get back to stand on Clive's Point or Britt's Point, but we have memories of it in the pictures we took and the rhododendrons we saw. Kyongnosla, Lachung, Lachen, Yumthang, Yakshay, going back for Rhododendron wightii, planting R. arboreum - we'll remember it all.

Clive Justice, a landscape architect, member of the Vancouver Chapter, and recent recipient of the ARS Gold Medal, is a frequent contributor to the Journal.

by Chase Dooley