JARS v58n3 - Mr. Magor and the North American Triangle: An Historical Perspective

Mr. Magor and the North American Triangle: An

Historical Perspective

With particular reference to the establishment and the significance of the

"connection" between James E. Barto of Junction City, Oregon, and E.J.P. Magor of Lamellen Garden, Cornwall,

England

John M. Hammond

Bury, Lancashire

England

"If you would seek a monument, look around you"

Introduction

Over the years a number of articles in the Quarterly Bulletin, the Journal A.R.S. and other publications have made passing reference to the support that the North American rhododendron "pioneers" received from key gentlemen gardeners and institutions in Great Britain and Ireland in the years between WWI and WWII. Many of the scant details that have been published are not referenced and, collectively, they do not provide a substantive record of the people, places and plants involved. This article looks at the story from a different perspective and aims to explain how the "connection" between two of these personalities, James Barto of Junction City, Oregon, and E.J.P. Magor of Lamellen, Cornwall, was founded, how it evolved and the cause of its subsequent demise.

Past articles in the Quarterly Bulletin and the Journal A.R.S. have provided an overview of the life and work of James Elwood Barto. Each article has contributed further details to form what is still a very hazy picture of this remarkable pioneer and, in some regards, there remain more questions than answers. Inevitably, as none of published material was written in liaison with Barto himself, there are discrepancies and chronological differences in the content of these articles. From the overall material presently available, it is possible to put together a more realistic time-line that corresponds with what is known about the other key personalities in this story. By way of setting the scene, and for comparative purposes, some background has been provided that covers the period that Barto set up home in Oregon. Themain sources for further reading about Barto himself have been listed in the references, of which the article by Dr. Carl H. Phetteplace, a charter member of the A.R.S. and one of Oregon's outstanding physicians and surgeons, is the most definitive.

|

|

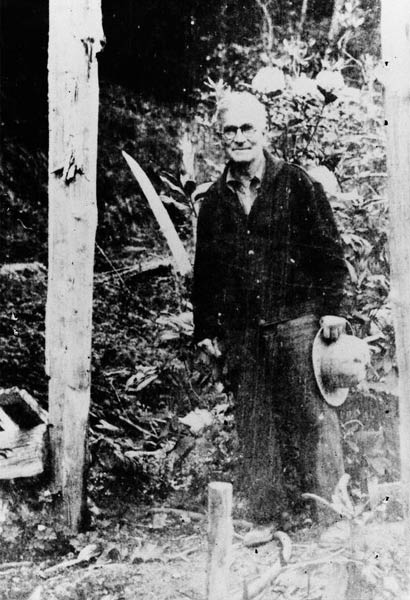

This previously unpublished photograph of Mr. Magor, taken

towards the end of his life, is one of only two photographs known to exist and probably dates from the mid-1930s. Photo courtesy of the Magor Family, Lamellen |

Another individual about whom little has been published is E.J.P. Magor. His name is usually referred to as Mr. Magor in past articles so for continuity we will do likewise. This somewhat quiet English gentleman, who observed the etiquette of the Victorian and Edwardian eras, was in his own way a remarkable, if unrecognised, pioneer. Other than in the publications within the County of Cornwall there are few references of any substance in regard to him and relatively few details have been published in regard to the garden he created at Lamellen. A number of correspondents have asked if further details are available about Mr. Magor's background, the history of Lamellen garden and the origin of the plant material that was sent to Barto. So, these deficiencies will be addressed at the outset.

Other correspondents have asked if more information is available about the "connection" between Barto and Mr. Magor, and the origin of the wild collected seed that Barto used to raise a wide selection of Joseph J. Rock's plants. These deficiencies will also be addressed with the aim of providing a wider perspective on two men, living a world apart, and the forging of a special relationship that was not hindered by one's station in life, or hampered by the highly competitive arena that encompassed the introduction of new species and new hybrids in Britain and Ireland.

Given that it is over sixty years since the death of all the key players in this story it is unlikely that a verifiable sequence of events will ever be known that led to the Barto-Magor "connection"; however, there are now sufficient pieces of the jigsaw in-situ for a probable sequence of steps to be suggested. Whilst this article is a means for moving the story forward it needs to be emphasised that it has not been possible to substantiate some aspects of the scenario. Nevertheless, it is possible to be definitive, as a result of research work carried out at Lamellen, as to the sources of the rhododendrons that were raised in this plantsman's garden and the origins of the wild collected seed. Threads from other historical background notes have been woven into the narrative as these provide a much clearer perspective of Mr. Magor's acquaintances, many of whom walk across the pages of this story. Whilst some readers may not recognise the names of these acquaintances, all in their own way were "characters" in the individualistic sense of the word, with influence in many spheres of life. Intertwined in the commentary is the part that Mr. Magor and Lamellen played in bringing rhododendrons to a wider audience in the years prior to WWII.

|

|

Lamellen House stands sentinel at the head of the valley and this view is taken

high

up on the west bank above the Main Drive that sweeps around in a long curve as it falls away towards the ponds. Beyond the House and in front of the farm and other buildings is the nursery area and greenhouses where Mr. Magor raised his species seed and hybrid seedlings. Photo by John M. Hammond |

The Origins of Lamellen

First appearances can be deceiving as Lamellen is far older than the early-Victorian house would suggest. There is an entry for "Lamdmanual" in the Doomsday Book for at least one house on the site in 1086. By around 1280 this had become "Lamailwyn," meaning "Valley of the Mills" and the 1698 date stone set in the western elevation of the present structure is from the house built on the site by Samuel Furnis. In 1825 Elizabeth Ann Moyle, the only surviving child of Samuel Furnis's grandson John Furnis, and heiress of Lamellen, married John Penberthy Magor of Penverton, Redruth. The Magor's were bankers at Kenwyn, near Redruth, and were also involved in the founding of Redruth Brewery. Together they rebuilt the earlier house and regularly stayed with their cousins, the Hext Family of Tremeer, to oversee the reconstruction. Work was completed in 1849. Tremeer, "just across the fields" from Lamellen, has benefited substantially in terms of plant material as a result of the continued relationship between the owners over many years.

When John and Elizabeth came to live at Lamellen the valley was mainly pasture and parkland. This is reflected in a fading photograph from around 1900 that depicts wide swaths of open grassed areas around the house. Records indicate that the family had a long-time interest in gardening and their connections with the Royal Cornwall Horticultural Society date back to at least 1838. Around this date James Veitch, who had recently relocated his nursery closer to Exeter, had the foresight to realise that the key to his company's prosperity lay in the improvement of techniques for seed germination and cultivation. He lured a pro mising young man named John Dominy away from a rival nursery with the aim of building-up his "team." Dominy turned out to be a wizard propagator and in 1842, just as the cases of William Lobb's seed collections in South America were spasmodically arriving at Topsham Dock at the head of the Exe estuary, he suddenly left Veitch's to work as Head Gardener for John P. Magor. James Veitch's frustrations at loosing his best nurseryman must have been immense as he spent the next five years trying to get Dominy back; he eventually succeeded in 1846. This scenario suggests that John Magor had a considerable involvement in gardening. One of the first things that John and Elizabeth had done on arrival at Lamellen was to construct a new greenhouse for their orchid collection. Around 1844, whilst working for John P. Magor, Dominy had worked out a methodology for hybridising successfully with orchids.

In 1861 one of John and Elizabeth's daughters, Mary Ann, married John Thomas Henry Peter of Chyverton another family with an interest in gardening. He died in 1873 and they had no children. The two eldest sons died prior to their father, John P. Magor, who in 1862 suffered a heart attack and was found dead on a train when it arrived at St. Kew Highway, the nearest station to Lamellen, on the London & South Western Railway line to Wadebridge and Padstow. Lamellen Estate then passed to his third son, Edward Auriol.

Edward Auriol Magor married in 1873 but passed away at the early age of 34, leaving three sons and two daughters. This led to the eldest son, Edward John Penberthy Magor, spending much of his boyhood at Chyverton with his "Aunt Mamie." This historical background helps to explain just a few of the many complex family relationships that existed between the owners of the great houses and gardens of Cornwall. Many of these family "connections" have remained insitu across the generations.

The Development of Lamellen Garden

Edward John Penberthy Magor started gardening at Lamellen in 1901 at which date his mother was still living in the house. He had dreams of inheriting Chyverton estate from his Aunt Mamie whose husband, John T.H. Peter, had died some years back in 1873. But his hopes were dashed when his aunt decided to leave the estate to a distant member of the Peter Family, even though he was no relation of her husband's. Sadly, shortly after the aunt died in 1915, Chyverton was sold-on by the inheritor. The Holman Family, who subsequently created the now famous garden to the east of the House, bought the estate.

In 1901 Mr. Magor had to all intents and purposes an empty palate to work with at Lamellen. Standing in an elevated position near the top of a small valley the House looks out across the wide expanse of the garden as the valley sweeps around then narrows as it runs down to meet the River Allen near the Lodge and entrance gates. Mr. Magor reminisced in later years in the pages of The Rhododendron Society Notes that in 1900 he visited the Temperate House at the R.B.G., Kew, and had been stunned by the sight of a large R. grande . He decided there and then that rhododendrons were the plant for him and he needed to find out more about them. Between 1901 and 1906 Mr Magor travelled widely, visiting R.B.G., Edinburgh, R.B.G., Kew several times and Glasnevin Botanic Garden. His ledgers record the rhododendrons given to him by these institutions as well as plants that came from Mr. Acton at Kilmacurragh and Mr. Daudbuz at Killiow in Ireland.

From the very start he was planting rhododendrons which he purchased from Richard Gill of Tremough, James Veitch of Exeter & Coombe Wood, James G. Reuthe of Bromley, Kent, T. Smith of Daisy Hill Nursery, Newry , Gauntlett of Chiddingford, Surrey, R. Barclay Fox at Penjerrick, Jonathan Rashleigh at Menabilly, and even the dwarf Siberian species Rhododendron camtschaticum , R. anthopogon and R. parvifolium (now R.lapponicum Parvifolium Group) from Messrs. Hegel & Kesselring of St. Petersburg in 1903.

Mr. Magor kept meticulous records of all plant and tree acquisitions, including the locations they were planted and their date of their first flowering; but for the purposes of this article we will concentrate on the Rhododendron genus. Interestingly, R. crassum , a Forrest introduction of 1906, first flowered in Britain at Lamellen in 1914. Very early on he realised the advantage of growing rhododendrons from wild collected seed and accompanied Reginald Farrer on his 1909 expedition to Switzerland to collect alpines. Farrer's expeditions to the European Alps were usually of a month's duration and the party "travelled hard and far," an approach that was to be his undoing in later years. Farrer invited Mr. Magor to join him on his first expedition to China in 1914 but he had recently married Gilian, so, somewhat reluctantly, he let William Purdom go in his place.

|

|

|

|

Looking back along one of the paths that radiate from the top of the Main

Drive in

the spring of 2001. The Upper Terrace, cut into the hillside, forms a relatively level access pathway along most of its length and is home to a large and diverse collection of both species and hybrid rhododendrons, intermixed with magnolias and other companion plants. Photo by John M. Hammond |

Standing guard to the driveway in front of the House, and covering itself

with

flowers every spring, is R. 'Cornish Cross'. It is thought these came from Samuel Smith at Penjerrick and date from 1885 when Mr. Magor's father also planted a range of conifers and deciduous trees. Photo by John M. Hammond |

In 1912 Mr. Magor inherited the Lamellen Estate by which time he had made major steps in laying out the garden. Contrary to the widely held present-day perspectives, inheriting an estate in the early-1900s was not a recipe for an easy life. The estate encompassed a number of farms, houses, buildings, workers and tenants that generated a plethora of matters that needed to be attended to in addition to his banking interests.

Mr. Magor was a very private individual in the time-honoured traditions of the Victorian era. It is very difficult for many present day gardeners to perceive exactly what this means and a few words of explanation will help to set the scene. In the course of Mr. Magor's work in the family's banking business he would have compartmentalised the transactions with each of his many "customers" to maintain the levels of etiquette that were expected and, in a similar manner, this way of approach spilled over into his personal life. Mr. Magor also segregated his business interests from his home life as much as possible, so his gardening interests were, to all intents and purposes, taken forward in another world with a completely different "set" of friends, even if it involved some individuals that happened to use the bank.

Mr. Magor tended to maintain his gardening friendships via correspondence, even if a friend happened to live relatively close by. It is often forgotten that the mail service was infinitely better pre-WWII than it is today. So, there was an ongoing exchange of letters between John Charles Williams at Caerhays Castle and himself or with George Johnstone of Trewithen, amongst others. Even the correspondence between individual friends was compartmentalised to avoid any inadvertent chance of causing offence by divulging personal information to a third party. The more detailed discussions took place through the medium of a formal invitation to dinner and this provided an opportunity for a walk around the garden, an inspection of the greenhouses and propagation work and for the exchange of plants material or seed.

|

|

|

|

Looking from the House down the Main Drive as it sweeps around the valley

floor

towards the ponds. Remnants of the rapid-growing radiata pine shelter-belt stand at the top of the bank whilst the blood-red R. arboreum came "...from Smith of Penjerrick in October 1909 and planted in the 'New Clearing' by Upper Terrace." Photo by John M. Hammond |

After crossing the Main Drive the outfall from the Upper Pond is channeled

to contain

the momentum of the stream as it rushes down to the Lower Pond. At this point the valley is relatively wide and both banks contain a wealth of plants and trees. Photo by John M. Hammond |

The status of a particular individual within the closed ranks of the landed gentry was not only judged on the size of the estate and the house(s) they owned, but also took account of the gardens, the woodlands, together with the rarity of the plants and trees they contained. So, there was considerable competition to obtain desirable plant material and trees, including newly introduced species and new hybrids from both home and overseas. Even the rare plant material that happened to fall into the hands of the key nurserymen of the day tended to find its way to favoured "customers" amongst the landed gentry. But that said, and bearing in mind it is dangerous to generalise, the nurserymen kept themselves to themselves very much the same way as the landed gentry did. When the formation of a Rhododendron Society was mooted at Lanarth, Cornwall, in March 1915, then founded at Chelsea Show of May 1916, its original members were all gentlemen of means and by invitation only. Amongst the initial total of sixteen members, none of whom were nurserymen, was Mr. Magor. How did this very private individual come to be a correspondent and key supporter of the endeavours of James Elwood Barto?

|

|

Discussions with the Barto Family have confirmed that this is

the only photograph known to exist of James Barto. He is stood in front of a large, but unidentified, rhododendron in flower shortly before his death in 1940. Interestingly, the photograph was stapled to a letter date 7/XI/1936 from Mr. Magor to Barto. Photo courtesy of of the Lane County Historical Museum, Eugene |

James Elwood Barto and The High Pass Road Homestead

James Elwood Barto, born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on June 14th, 1881, was a U.S. Naval shipyard specialist-carpenter by trade, having first enlisted in 1905. After two periods of enlistment he married Ruth Ellen Lampson in 1913 and they made their home on the north side of Chicago. At the outbreak of WWI he re-enlisted as a warrant officer in the Navy. After the WWI armistice was signed, Barto travelled west to Oregon in 1920 having heard that certain land was available to veterans for homesteading. Barto filed a claim for around 160 acres of land densely covered with Douglas fir and interspersed with oak, maple, alder, wild cherry and red cedar on the High Pass Road, 10 miles west of Junction City. Water, sufficient for domestic purposes, was available from Bear Creek, a small stream that flowed through the property.

He returned home to Chicago, loaded his wife, kids and whatever else they could fit into an old chain-driven truck and headed back west to Oregon. As the family would later recall, this was a 2,700-mile nightmare of a journey and several weeks were to elapse before they arrived in Eugene in October 1920. Here the family set up camp for the winter on land to the north of Skinner's Butte, close to the Willamette River. Barto found work in Eugene as a carpenter on the construction site of a fraternity house at the University of Oregon campus.

At weekends he worked long hours at the High Pass Road property clearing timber and an under-story of wild blackberry, salmonberry, huckleberry, vine maple and other shrubs on a small area of land where he erected a log cabin. In June 1921 the family moved to the new homestead. Barto continued to find carpentry work, sometimes in Corvallis and other surrounding towns, but mostly in Eugene. He was regarded as an excellent cabinet-maker and finisher. His work tended to take him away from home from early on a Monday morning until the following weekend when he would work long hours back at the homestead. Mrs. Barto would later recall how she and the children would hold the lantern whilst he worked into the night. A level piece of land was located on the property, that he is said to have purchased in 1923, and, with aid of his elder children, he constructed a home. The family moved into their new home in 1925.

In the same year he found carpentry work constructing greenhouses at Raup & Yorks's nursery at Skinner's Butte on the banks of the Willamette in Eugene. Leonard Raup was a pioneer grower of potted azaleas for the wholesale florist trade and is said to have been a well-informed and practical nurseryman. Barto developed an interest in rhododendrons and azaleas whilst working at the nursery and learnt much of his cultivation methodology from the work of Raup, who provided him with seed to experiment with at the homestead. Raup told Barto that rhododendrons and azaleas were not yet fully appreciated and that they would eventually be recognised as the finest of all shrubs. The seed germinated well in a tray placed on top of Mrs. Barto's chicken incubator that was heated by a kerosene lamp. Barto was "hooked" on rhododendrons. He moved the seedlings into a small cold frame that he had constructed alongside the house and began to make enquiries as to where he could find out more about the genus.

In 1926 Barto began construction of the greenhouse that would be needed to support the propagation of rhododendrons that he had set his mind on raising. Greenhouse heating was provided by pipes circulating warm water under the beds, fed from a wood-fired boiler during the cold winter nights on the High Pass. Eventually about five acres were cleared around the house with the aid of their old horse "Shorty," so fir and alder were plentiful to fire the furnace. The older sons, who also helped with the construction of the lathhouses, aided him.

As each weekend drew to a close, before returning to work, Barto would lay out instructions for the tasks that needed to be done whilst he was away. In the wintertime this often included getting up in the middle of the night to replenish the fuel in the wood-fired furnaces serving the greenhouses. It is said that Elwood, the second oldest son, was the one that helped his father in the greenhouse. Another major feat was the installation of 2,700 feet of two-inch irrigation pipe that "Shorty" hauled up the mountain trail to provide the Barto with a water supply for his plants during the hot days of summer. Barto had secured water rights to a spring on adjacent government-owned land and constructed a small dam to create a reservoir.

So it was that in around 1926 Barto began to propagate rhododendrons at the homestead and soon the greenhouse was filled with flats of small seedlings, all labeled and recorded. But he still needed to acquire plant material and advice on their propagation and cultivation. How was this carpenter, with seemingly limited financial means, able to obtain seed from the plant hunting expeditions of the key collectors in the years prior to WWII? How was he able to amass so wide a range of plant material collected by Rock? How did he become successful in raising plants from seed and then grow them on at an apparently high growth rate to enable an early assessment of the plant's overall performance to be made?

Mr. Magor's Wild Collected Seed Acquisitions and His Hybridisation Programme

In 1899 E. Harry Wilson was chosen by Sir William Thiselton-Dyer, Director of Kew R.B.G., to collect plants for the now world famous nursery of James Veitch & Sons at Coombe Wood, Kingston on Thames. C.P. Raffill, Assistant Curator at Kew R.G.B., tells us in a letter to Del and Rae James of Eugene, Oregon, dated 13th December, 1948:

The British firm of James Veitch and Sons, nurserymen of Chelsea, London, sent out to China my old and esteemed friend, E. Harry Wilson as a collector. We had both been employed at Birmingham Botanic Gardens and afterwards came to Kew as students. He was here at the Botanic Gardens, Kew in 1897 and I came in 1898. We both studied Botany together but he was a year in advance of me... We both passed advanced Botany courses and both of us intended to be Botanists but Wilson's funds ran short and he could not continue his studies, so he took a post with the great British nursery firm, James Veitch... When Veitch began selling the rhododendrons raised from Wilson's 1899-1902 collections in China, a handwritten listing of the plants that were available, dated 20th September, 1907, was sent to Mr. Magor. Interestingly, Veitch's listing refers to the seed collection number and flower colour; no species names were used. From that year onwards Mr. Magor received a listing quoting the species and numbers of each plant that would be available that particular season. Mr. Magor reserved a selection of plants each year that Veitch had new introductions available; these are itemised in his ledgers and were delivered to Lamellen in October or November of that year.

Wilson continued to collect exclusively for Veitch on the 1903-1905 expedition and all told Veitch raised thirty-one species of rhododendrons that were distributed under forty-nine seed numbers. Ironically, Wilson's very success was to lead to the termination of his contract. Not only were his plant collecting expeditions deemed to be a great success, his success in raising the Chinese introductions, in collaboration with George Harrow at Coombe Wood, was to cause James Herbert Veitch concerns that Veitch's stock would flood the market. So J.H. Veitch wrote to Thiselton-Dyer at Kew on October 2nd, 1906:

After five years most satisfactory service Wilson's engagement is terminated with my firm… Very shortly there will be no work for him here… and I am taking the liberty of troubling you in the hope that during the next few months some suitable position may be open. Kew found him temporary work but he soon took a botanical assistant's post cataloguing collections from Asia for Imperial Institute of Science in London. On his first expedition Wilson had travelled to China via the U.S.A. and had met the somewhat autocratic Professor Sargent at the Arnold Arboretum, Boston. In the years that followed Sargent became extremely keen to engage someone to collect in China on behalf of the Arnold Arboretum and an American syndicate of wealthy individuals, but all his advances had been swept aside. In a letter dated 19th June, 1947 C.P. Raffill tells us:

I stayed on at Kew and soon became a permanent official of the Gardens. Wilson meanwhile became famous as a collector and after two journeys in China, Professor Sargeant of the Arnold Arboretum came over to this country and induced Wilson to go out for the Arnold Arboretum as their official collector...From that time Wilson threw in his lot with the famous Professor Sargeant and made several trips to various parts in China, India, Japan, Australia and New Zealand for and on behalf of the Arnold Arboretum.

In 1907 Sargent came over to England, doggedly brushed aside Wilson's refusals and, after protracted negotiations, he secured Wilson's agreement to make two further plant-collecting expeditions in 1907-1908 and 1910-1911. These negotiations appear to have involved J.C. Williams of Caerhays Castle, Cornwall, who, between 1909 and 1911, distributed seed of twenty-eight species under thirty-five seed numbers from Wilson's latter expeditions. One of the recipients was Mr. Magor. As was the case with later plant collectors it is highly likely that Wilson would have been invited to dine or stay with the owners of major Cornish gardens who had purchased selections of plants raised from his seed by Veitch or shared the distribution of his later seed collections. In this way Magor would have met Wilson and had the opportunity to discuss matters relating to the collection of seed and the methodology of raising plants. Inexplicably, these two men from entirely different backgrounds would, in the passage of time, become the key facilitators in this story.

With a view to reducing stock Veitch's issued a special "China" catalogue in 1909 and others followed over the years to 1913, but in reality this had little if any effect as hundreds of packets of seed from later collections continued to arrive for germination at Coombe Wood. Just as Veitch's were distributing their 1909 "China" catalogue, by uncanny co-incidence, Wilson arrived back at the R.G.B., Kew on 17th May from his third expedition, having travelled overland via Peking and Moscow. He immediately hurried down to Coombe Wood to see how his earlier introductions were progressing, but there is no record of what he thought about Veitch's catalogue. In parallel with these problems the retirement of James Herbert due to illness, followed by his death a year later, was a devastating blow to the Veitch family. Slowly they managed to pick up the pieces but by 1914 the company was in real difficulties due to staff leaving to take up service in WWI. By 1914 Sir Harry Veitch was 74 years old and there was no one to "inherit" the Veitch dynasty. So, not long after Wilson returned from his last expedition and, just as his original collections were reaching the flowering stage, it was decided to wind up the Coombe Wood business. A huge clearance sale of nursery stock commenced on November 10th 1914 resulted in many large lots being disposed of in an auction at Coombe Wood that ran for ten days. Among the stock of 6,000 named rhododendrons and hundreds of unnamed Chinese species were many of Wilson's original collections. Prior to the sale Sir Harry Veitch invited a number of old friends and customers to have first choice of the specimen plants. Amongst those of the gentry who took up the invitation were the names of many of the personalities whose names walk across the pages of this story. Many of the plants were all relatively small, some named and some under Wilson's numbers and it was these gentlemen gardeners who understood the significance of the material being sold.

However, curious gardeners who were excited by the opportunity of being able to acquire newly introduced species purchased the remaining Wilson plants. They had no idea if they would grow in the soil conditions in their gardens and some plants did not survive in the chalky soils of Southern England. So, Wilson's early collections were not distributed as widely as they might have been. Peter Veitch continued to run the Exeter Nursery up to his death in 1929, when his daughter Mildred took over the business. Unfortunately, Veitch's plant and business records have not survived. It is said that Mildred Veitch had the mountains of accounts, correspondence, plant records and catalogues destroyed on a large bonfire around the time of her father's death.

Lamellen garden benefited enormously from Mr. Magor's friendship with J.C. Williams, then Lord Lieutenant of Cornwall who, jointly with the R.G.B., Edinburgh, sponsored George Forrest's 1910-11 expedition to China. Mail and time-conscious traffic such as seed and plant material, carried by packet boat from the Far East and destined for delivery in England, normally entered the country by the port of Falmouth as this was the most westerly safe harbour for the sailing ships to use. Mail, and other such traffic, was then shipped overland by road or rail. But, it was not unknown for the mails and other traffic to be over-carried and, presumably due to difficulties entering the Fal estuary in adverse weather, the packet boat sailed on to dock at Leith, near Edinburgh, causing all sorts of chaos for the consignees. Falmouth remained a key port until well after the turn of the century. It was not until steamships of the Transatlantic Steamship Company were awarded the contract for the carriage of the mails that Southampton and Liverpool gradually took over the Far East traffic. In due course the seed from Forrest's expedition arrived at Werrington Park, a second estate owned by J.C. Williams at Launceston on the border of Devon and Cornwall, and he personally made-up the packets of rhododendron seed and then distributed them to syndicate members and his friends. Williams supervised the germination and plant cultivation at Werrington Park and initially the seedlings were planted out there rather than at his story-book castle at Caerhays. Mr. Magor received seed of most of the species from this expedition and subsequently from the 1912-15, 1921-23 and 1924-26 expeditions. With the arrival of Wilson's and Forrest's seed from China Mr. Magor ceased purchasing plants and concentrated on raising plants from seed.

Mr. Magor always regretted not being able to go plant-hunting with Farrer in 1914; however, Sir George Holford sent him seed from the expedition and these were sown in early-1915. Sir George Holford was a frequent visitor to Caerhays and J.C. Williams remarked that he was very discerning and difficult to please in terms of plant material. Sir George greatly augmented the collection of trees and shrubs that his father, Robert Stayner Holford, had founded at Westonbirt House and Arboretum in 1829. Following Sir George's untimely death in 1926 Westonbirt House became a girls school and the Arboretum was subsequently taken over by the Forestry Commission. Westonbirt is now the finest and largest arboretum in the British Isles, covering 600 acres of beautifully landscaped grounds and contains a significant collection of rhododendrons dating back to the expeditions of Hooker and Fortune. Inexplicably, Westonbirt is not often mentioned by rhododendron enthusiasts and would appear to be infrequently visited by them.

By the time Mr. Magor was sowing Farrer's seed Great Britain was well entrenched in the First World War. Many well-known gardens were severely affected by the loss of all their younger garden staff and Cornwall was no exception. By the time hostilities had come to an end many large gardens had become overgrown and never recovered from this situation, a noteworthy example being Heligan.

Another friend, Captain W. H. Schroeder, who started to grow rhododendron species at Attadale, near Inverewe, Ross-shire, in 1920, sent him seed from Rock's 1923-24 and 1925-26 expeditions. The volumes of seed that Rock collected were immense and often contained consecutive numbers of the same species. Whilst the sheer number of seed lots tended to cause difficulties for the gardeners who were faced with raising the seed there were also some fringe benefits. In common with many other institutions Glasnevin Botanic Garden did not have the financial resources to subscribe towards the expenses of plant hunting expeditions; however, keen gardeners such as Lord Headfort and Lord Rosse made sure that Glasnevin did not want for wild collected seed. In 1934 over 300 packets of rhododendron seed from Rock's 1932 expedition were sown in the nursery at Glasnevin Botanic Garden and duplicate seedlings were sent to other major Irish gardens where the soil was more suitable than that at Glasnevin. Other smaller gardens, within and without Ireland, also benefited from this exchange and distribution arrangement. In a similar way other contributors to the Rock expeditions had surplus seed and seedlings to share and exchange with other enthusiasts.

In keeping with his banking background Mr. Magor meticulously recorded in his ledger under the title of Chinese Rhododendrons the date he received each seedlot, the name of the species (where known), the dates the seed was sown, germinated, potted on, the location and date that the seedlings were planted out in the garden, the date and colour of the first flowering and names of other recipients of the seedlings. With the large quantities of seed coming to hand, together with the need for assessment of the huge quantities of seedlings being raised of species material that had not been seen previously by the recipients, it was little wonder that the learning curve was immense. Names of many of the species were subsequently amended by Mr. Magor in the ledgers over the years in the light detailed correspondence that dates from 1916 with J.C. Williams and Professor Bayley Balfour (later Sir Isaac), Regius Keeper at R.G.B., Edinburgh who made the first attempts to classify these new collections from China.

Following Professor Bayley Balfour's death in 1922 the correspondence continued unabated with H.F. Tagg and Sir William Wright Smith at Edinburgh, both being instrumental in taking the identification and classification work forward. These correspondents were well aware of the possibility of hybrids occurring in the wild in areas where two species met, and of the resulting taxonomic difficulties or confusion. They were also concerned with the variation in a species caused by a wide geographical distribution with differing climatic conditions. That their doubts were justified, especially in the case of rhododendrons raised from Wilson's and Forrest's seed, is well demonstrated by the revisions of many series in the genus in later years.

Hybridisation was a subject that fascinated many early gentlemen gardeners with an interest in rhododendrons, particularly in Cornwall, and Mr. Magor was no exception. He commenced his hybridisation programme with cross #1 in 1905 and, having corresponded with Professor Bayley Balfour about the correct way of approach, he made primary crosses with the species. Most of his hybrids bore "portmanteau" names made from the first part of the two parent species names, with the seed parent placed first, as recommended by Balfour.

|

|

Looking across the Lower Pond and back up the valley with the Main Drive

just visible on the extreme left. Renovation work and replanting the garden have been ongoing for many years, and the long-running sequence of "projects" has reached this area around the Lower Pond. Photo by John M. Hammond |

Few rhododendron enthusiasts realise just how much hybridisation work Mr. Magor accomplished, as by the time of his death his listing of crosses had reached #2044, probably a record for a British plantsman with no commercial interests. In comparison Lionel de Rothschild made 1,210 crosses in a twenty-two year period, so the average number of crosses per year was very similar. As a precursor of the approach used in more recent years at Meerkerk Rhododendron Gardens, Whidbey Island, Washington, he planted the hybrids out on trial in the garden in groups of three with a view to keeping the best. A total of 100 crosses were named of which 80 were registered in Mr. Magor's lifetime, over twenty others have been registered since and there are many others that should have been named. Probably the best known are the Damaris Group, the Lamellen Group, R. 'Cinnkeys', R. 'St. Breward' and R. 'St. Tudy''. Shortly prior to WWII the first of these crosses was remade a number of times by other gardens so there is now R. 'Townhill Damaris', R. 'Logan Damaris' and, thirty years later from the same cross at Tremeer came, R. 'Cornish Cracker' and R. 'Cream Cracker'. This resulted in the 1989 renaming of the original cross as R. 'Lamellen Damaris'.

Lionel de Rothschild had a high regard for his Cornish mentors, particularly J.C. Williams at Caerhays and P.D. Williams at Lanarth who became his horticultural godfathers. In a similar way he respected Mr. Magor's approach to hybridisation and a good many batches of his seedlings were taken back home to Exbury. Whilst walking around Exbury on 21st March, 1938, Mr. Lionel noted, "A fine scarlet hybrid of MAGOR'S—'Daphne' - with its curious double calyx is a pretty dwarf bush and makes a fine splash of colour against the dark fir trees." And again on 5th April, 1938, "Haematodes x blood-red arboreum of MAGOR was fully out with fine trusses of amazing scarlet. The plants I have are quite first class and are a great credit to the raiser." This latter cross would appear to be unnamed whereas R. 'Daphne', a 1921 cross of R. 'Red Admiral' x R. neriiflorum , was named after Mr. Magor's daughter-in-law and received an A.M. (R.H.S.) in 1933. Many of Mr, Magor's crosses have been used by later generations of enthusiasts in their hybridisation programmes.

Visitors to Lamellen

As late as 1925 the exclusive Rhododendron Society only numbered twenty-three in total. E.H. Wilson, who had been elected as an honorary member, commented that it was illiberal for the information being distributed to members to be classified as confidential. Lionel de Rothschild was a key instigator of discussions in 1925 as to the practicability of opening up the Society to other gardeners who were requesting membership. In 1927 a new organisation under the title of the Rhododendron Association was formed (incorporated 1928) and was open to all who wished to join, subject to election.

It is said that Mrs. A.C.U. Berry of Portland recommended Barto for membership and he subsequently maintained this for the rest of his life. However, the original Rhododendron Society continued in being as a private organisation with a fixed membership. From 1927 until the 1939 outbreak of WWII key members of the Rhododendron Society met each spring at Lamellen, the usual attendees being:

Lionel N. de Rothschild of Exbury, Hampshire

Henry McLaren of Bodnant, North Wales (later the 2nd Lord Aberconway)

Colonel Stephenson R. Clark of Borde Hill, Sussex

J.B. Stevenson of Tower Court, Surrey (attendee from 1929)

H. Armytage Moore of Rowallane, Northern Ireland (attendee from 1929)

Sir Frederick Moore (retired from Glasnevin, Dublin in March, 1922

and usually accompanied H. Armytage Moore)

Lord Headfort of Headfort, Southern Ireland (attendee from 1929)

Lord Stair of Castle Kennedy, South West Scotland (attendee from 1929)

E. J. P. Magor of Lamellen, Cornwall

Many of these attendees were given, exchanged or purchased large selections of rhododendrons whilst visiting Lamellen and other gardens in the area and in this way Cornish plants, both species and hybrids, spread all over the Great Britain and Ireland.

Typical of the attendees, whose name may not be familiar, was Mr. Magor's friend Lord Headfort (1878-1943) whose garden and arboretum at Headfort House, Kells, Co. Meath, Ireland, had been laid out by him in the same time frame as Lamellen. Like many other Earls who laid out gardens on a grand scale, Geoffrey Thomas, the 4th Earl, had acquired the knowledge and dexterity of a forester, knew exactly what he wanted and had ample financial means to take his projects forward. In his lifetime Lord Headfort employed a sequence of excellent head-gardeners and it was no accident that in 1912 he acquired the services of William Trevithick, a Cornishman who became famous for raising rhododendron hybrids on the Estate. When George Forrest died in Burma, in 1932 at the age of 40, a small garden was established by Lord Headfort to the east of the House in memory of his friend. Many of the dwarf rhododendron species collected by Forrest in the Eastern Himalayas were planted in the garden. Lord Headfort sent Mr. Magor seed from Kingdon Ward's 1921, 1922 and 1924-25 expeditions.

The American Triangle and Its "Connection" with Mr. Magor

George Fraser emigrated in 1881 from Scotland to Canada and arrived in Winnipeg, Manitoba, in 1883, at that time the end of the line on the embryo Canadian Pacific Railway. After three difficult years trying to raise flowers and vegetables in the prairie weather he headed west in 1886 to Victoria, B.C. and, in the search for land suitable for raising rhododendrons and heathers, purchased 256 acres of native bush in 1892 for $256.00 at the isolated frontier location of Ucluelet, on Vancouver Island, B.C. Born on 25th August, 1854, at Lossiemouth, Morayshire, near Inverness, he commenced his gardening career at the age of 17 at Christies Nursery, forest tree specialists, in Fochabers near the mouth of the Spey. He served his apprenticeship at nearby Gordon Castle as a gardener, but even with a horticultural background as head gardener at Auchmore, Perthshire, prior to emigration, he had a hard struggle setting up in business as a nurseryman in Canada. He put up a shack at Ucluelet in 1894, cleared nine acres of land to start a nursery and was eventually able to make the cultivation of rhododendrons a hobby as well as a business.

Around 1907 Fraser, who was seeking sources of plant material, made contact with E.H. Wilson, who was back at the R.G.B., Kew, in a temporary capacity. In 1919 Joseph B. Gable, a nurseryman of Stewartstown, Pennsylvania, also made contact with Wilson, who by this later date was working at the Arnold Arboretum. Gable appears to have been searching for plant material and other nurserymen with an interest in rhododendrons, so Wilson put Gable in touch with Fraser, and so began a lifelong exchange of correspondence.

In 1919 Professor Sargent appointed Wilson as Assistant Director of the Arnold Arboretum but Wilson continued to travel extensively and later settled in the U.S.A. to work on his collections. It is known that in the early-1920s George Fraser corresponded with Wilson at the Arnold Arboretum seeking to obtain seed and Wilson probably provided Fraser with a listing of names to contact in England as he would have been aware of J.C. Williams's distribution network based in Cornwall. Amongst these names would have almost certainly been that of Mr. Magor.

Given that the seed and seedlings from new introductions were highly valued by the landed gentry and carefully retained within a known circle of "friends" in Great Britain and Ireland it is likely that the majority of Fraser's letters failed to get a positive response. Contrary to expectations, this was not the case in regard to Mr. Magor who had a more benevolent outlook, probably as a result of the plant material and help he himself had received in earlier years. So the first link in the chain fell in to place. Meanwhile the continuing correspondence between Fraser and Gable served to underline the problems that Gable faced in raising seedlings that could survive the extremes of the East Coast climate. In the mid-1920s Fraser decided to "introduce" Gable to Mr. Magor by mail so the two could directly discuss the performance of seedlings raised in Pennsylvania and, in particular, seed sent from Lamellen.

Around 1926 Barto contacted Mrs. A.C.U. Berry, a plantswoman of wide-ranging interests, who was constructing a large garden in an uptown area of Portland, Oregon. It is probable that in the mid-1920s these two individuals were the only enthusiasts in Oregon who were pursuing a serious interest in acquiring wild collected rhododendron seed and cultural information. At this date Mrs. Berry was well-connected in horticultural circles, was a subscriber to a number of major plant collecting expeditions and her contact details were probably given to Barto by Leonard Raup. As well as providing some practical help and sharing seed, she also gave Barto a list of names to contact. This list probably included the contact details for Ernest H. Wilson who in turn provided Barto with the contact details for George Fraser. The timing suggests that the seed acquired by Barto from Mrs. Berry probably came from Rock's mid-1920 expeditions.

Barto wrote to Fraser, who in turn exchanged some thoughts in correspondence with Gable about the "new kid on the block" prior to responding to Barto. Gable explained in a letter dated May 9th, 1960, to Carl Phetteplace of Vida, Oregon:

I think our first correspondence started with mutual acquaintance, with Mr. George Fraser of Ucluelet, B.C. and through Mr. Fraser I started a correspondence with Mr. E.J.P. Magor of Cornwall, England and received both seeds and pollen which I shared with Mr. Barto. Then I also grew many seedlings from Mr. Magor's seed and from Dr. Rock's collection which I knew would be tender here and I recall sending him several boxes of these by express. He, as you record wrote profusely and I was unable to keep up with him in that line. In due course both Fraser and Gable came to realise that they both had difficulty in servicing the deluge of correspondence, queries and requests for specific plant material that Barto generated, so Fraser wrote to Mr. Magor in early-1927 to "introduce" Barto by mail. This put in to place the "triangle" that became the North American end of the "connection" that corresponded with Mr. Magor. There is no evidence to suggest that Mr. Magor ever realised that Gable was sending on to Barto the seed and seedlings of species that were too tender to survive the harsh winters of the East Coast.

By 1930 Barto's seed and plant acquisitions were outstripping his facilities at the homestead, so a second greenhouse was constructed, also heated by a wood fire furnace. A larger second lath house was also needed and this was erected close to the creek. In 1932 Barto appears to have lost part of his records and correspondence, as in a letter dated July 8th, 1932, he asks Gable to resend him an availability listing of plants and also asks, "Can you please give me Fraser's address in British Columbia?" But Barto was also supplying plants to other enthusiasts during these years.

In the middle of a letter to Guy Nearing, another pioneer rhododendron nurseryman of Guyencourt, Delaware, dated March 8th, 1932, Gable interjects the following paragraph:

A West Coast grower who is interested is Mr. Theodore Van Veen of Portland, Oregon. He is acquainted with Barto and has been growing azaleas and rhododendrons etc. in a wholesale way for some years. Theodore Van Veen, a horticulturalist trained in Europe, emigrated to British Columbia in 1906, moved to Seattle in 1915 and was working in Durham, a suburb of Portland in the early 1920s. His son, the late-Ted Van Veen, explains it this way:

My Father worked in nurseries in Holland, Belgium, England, Canada and the United States. In Oregon he was the foreman for the J. B. Pilkington Nursery. At that time it was the largest nursery in the Portland area. The old catalogue I have shows that they sold several varieties of rhododendrons that were most likely imported from England. The Pilkington's had relatives there that I assume they imported from.

My Father began his nursery in 1926 as primarily a camellia and boxwood nursery. I was 10 yrs old then. When exactly he got into rhododendrons and became a specialist I do not know.

My Father got some of Barto's rhododendrons. I know they knew each other but to what extent I do not know. Theodore Van Veen initially grew azaleas from seed but he was determined to propagate rhododendrons from cuttings, a methodology that was in its infancy at the time. It is likely that his enquiries in to this technique brought him into contact with Leonard Raup and Barto. Raup's use of "cutting edge" techniques in raising azaleas in the 1920s would have provided both Barto and Van Veen with much to talk about in regard to raising rhododendrons.

Around this time Barto also contacted Mrs. Chauncey Craddock of Eureka, Northern California, who was another pioneer rhododendron grower. She is said to have been quite a character, imported rhododendrons directly from England and was another early member of the Rhododendron Association. Barto's family credited her with being a great help to him; she visited the homestead on several occasions and was conversant with the source of his plant material, future plans and cultural ideas.

Throughout the years up to the late-1930s Barto never showed any interest in growing plants commercially, although there were some nurseries that repeatedly requested that he propagate particular material for their trade. Records suggest he did occasionally supply small batches of plants but it is doubtful if any appreciable quantities were sold. In reality Barto was way ahead of his time and the market for rhododendrons, as foreseen by Leonard Raup some fifteen years earlier, had not yet developed. His son Merrill commented that over the years he gave away many thousands of plants to individual visitors who showed a kindred interest.

During the latter years of his life he became a government employee and worked on the laying out and construction of Civil Conservation Corps camps, and as an instructor to train the boys. His final work was with the State Forestry Department. None of this suggests that Barto had the means to finance contributions to plant hunting expeditions. What can be said for certain is that he was very ill in the latter months of 1936. In a previously unpublished letter from Mr. Magor dated November 7th, 1936 (recently located in the care of the Lane County Museum, Eugene):

I am so sorry to hear you have been very ill, but hope from your letter that you have recovered… What a pity the weather has treated your plants so badly, you have my sympathy...

Perhaps this was the onset of the illness that was to foreshorten his life. It is also known that at the time of the onset of this illness Barto was beginning to recognise the possibility of earning a living from his garden; he was anxious to quit the strenuous life that he had been carrying on and devote his full attention to his plant collection.

Seed Acquisitions, Hybridisation Programmes, Records and Correspondence

The above commentary on Mr. Magor's wild collected seed acquisitions, hybridisation programme and the listing of regular visitors to Lamellen serves to emphasise that he was uniquely well placed to provide both plant material and knowledge from detailed "hands-on" experience that dated from the time when "Chinese Rhododendrons" first arrived in Britain. Records indicate that he sent seed to the U.S.A. every year from 1927 until 1940, mainly in response to requests for specific species seed, and he often enclosed additional material including seed from his own hybridisation work. It is likely that seed was sent to Fraser in Ucluelet, B.C., for some years prior to 1927.

In a letter to Nearing, dated January 26th, 1939, Gable notes, "Never again I think do I wish to sow another such list of collectors numbers as that from the U.C. BG Rock expedition or the Magor hybrids." After 1930 pollen was also regularly sent in response to many requests and some years scions and seedlings were also forwarded.

Over the year s a number of North American commentators have suggested that a significant percentage of the seed obtained by Barto and Gable was undoubtedly the result of open pollination, hence of at least questionable authenticity. In the early years of the 20th century it was not realised that plants were unlikely to come true from open pollinated seed and this lesson was learnt the hard way, as was the realisation that some species were more promiscuous than others.

By the time that the "American Triangle" had become established the problems with open pollinated seed had been realised and, given that Mr. Magor was an extremely meticulous individual who carried out the majority of the propagating and hybridisation work himself, steps are likely to have been taken to avoid this problem. The same could be said of all the above listing of regular visitors to Lamellen, as each of them were either directly involved in raising species seed and also in their own hybridisation programme, or they closely supervised a head gardener who was known to be an excellent horticulturist.

Whatever Mr. Magor had he shared; but of course this meant that it included the products of "...a Himalayan rather than a Cornish bumble bee", as his son Walter was to comment in the early-1960s about hybrids originating from wild collected seed. Reference has been made earlier to Edinburgh R.B.G.'s concerns arising from the doubtful status of herbarium specimens of, and seedlings propagated from, many of the early collectors numbers. Interestingly, during the research work for this article, no references have been noted that suggests any of the plants that originated from the Barto homestead turned out to be hybrids rather than true to type species.

Past articles and surviving correspondence suggest that both Gable and Barto were "collectors" of rhododendron species rather than traditional gardeners. Their correspondence indicates they exchanged seed of specific collector's numbers and sought to extend their own species collections whenever the opportunity arose. Records also suggest that they requested specific collector's numbers in their letters to Mr. Magor and other correspondents in Great Britain. Not surprisingly, the Gable correspondence contains a number of comments referring to the difficulties of identifying which seedlings were true to type and which were hybrids.

Whilst Barto kept up an ongoing correspondence with Wilson and sent plant material to the Arnold Arboretum he also received plant material in return, including seed from Rock's 1920s expeditions. In addition he received seed of Rock's later expeditions from a number of sources including, Anton (Ancel ?) Brower on Long Island and Dr. Clement G. Bowers of Maine, New York.

Gable also received Rock seed from the U.S.D.A. at Glenn Dale and there was an on-going exchange of plants raised from Rock collection numbers between him and Barto. As noted above, it is likely that Barto also received seed from Rock's mid-192's expeditions from Mrs. A.C. Berry.

Mr. Magor's ability to source material and act as a facilitator was greatly enhanced by fact that his immediate friends in the world of rhododendrons were the key figures of the era, so he was able to source plant material from collections in other major British and Irish gardens. In the mid-1920s and '30s there was a "network" in-situ whereby the landed gentry, the arboretums and major public gardens freely exchanged plant material and serviced each other's needs. Typical of this was Mr. Magor's "introduction" of Gable to Lionel de Rothschild. "Mr. Lionel" was a very generous friend and took positive pleasure in sharing with others the good things that lay at his command. In common with Mr. Magor, social standing was of no account and the only passport to his society was a knowledge and love of flowers. As early as 1930 Gable was receiving both species, including Rhododendron fortunei and R. discolor (now R. fortunei ssp. discolor ) , and hybrid seed, such as L.R.791 R. wardii x R. discolor (now R. fortunei ssp. discolor ), from "Mr. Lionel" and by 1935 they were exchanging information about hybrids. Barto was also "introduced" at an early date to "Mr. Lionel" and received both species and hybrid material from Exbury. Incidentally, Gable's receipt of L.R.791 seed correlates well with the period in which the cross was made and "Mr. Lionel" later named a clone R. 'Inamorata', which gained an A.M. (R.H.S.) in 1950 with its soft-yellow flowers and a spotted-crimson flush in the throat.

Whilst on the subject of hybrids, "Barto's List of Plants," that accompanied the letters in Rudolph Henny's article of 1960, includes a number of hybrids. Some of these are almost certainly raised from material supplied by Mr. Magor and R. 'Gilion' on the listing is incorrectly spelt; this is in fact R. 'Gilian', an R. aucklandii ( R. griffithianum ) x R. thompsonii cross of 1912 that Magor introduced in 1923. (Although the IRR lists the cross as R. campylocarpum x R. griffithianum , the IRR listing is likely wrong.) It is a reverse cross of the R. 'Cornish Cross' parentage and its blood-red truss was awarded an A.M. (R.H.S.) in 1923. This is likely to be the plant that Dr. Carl Phetteplace refers to as 'Barto's Cornish Cross' in his article. There are others in the listing that can be identified and a their background explained from the details of hybrids in Mr. Magor's ledgers, but we digress and the origins of Barto's hybrids is perhaps an exercise for a future date.

Mr. Magor's ledgers and scrapbooks contain extensive plant records, articles and newspaper cuttings relating to plants and cultivation techniques, but very little in the way of correspondence. His family have suggested that to maintain confidentiality he may have destroyed correspondence that did not contain information of specific long-term interest.

But there is another possibility. In the early months of WWII a great many items of historical interest were destroyed by businesses and estates in Great Britain; generally they were burnt by the gardener, chauffeur or a handyman. This action was taken in accordance with advice issued under wartime conditions that recommended attics, lofts and cellars be cleared of paper and other combustible materials to help counteract the effect of the incendiary bombs that were being dropped indiscriminately by the German airforce.

However, one letter from Barto, dated 10th March, 1933, has survived in the pages of Mr. Magor's ledgers. This outlines Barto's methodology for the production of large flowers and for accelerating the flowering of seedlings. The letter has been reproduced in a separate box together with some pertinent comments. No correspondence from Gable or Fraser has survived.

A letter from James E. Barto, Junction City, R7D#1 Oregon to E.J.P. Magor, Lamellen, Cornwall, England, Dated March, 10th 1933.

Copied from E.J.P. Magor’s personal papers.

Dear Mr. Magor,

I use 1 to 2 oz of salt on a plant 30 in high with a 30 in crown, the heavier the compost the larger amount of salt to destroy the sour bacteria. One oz of Aluminium sulphate applied in not less than ⅓ oz dose dissolved in water. The salt to be applied in winter when the root action is absent. It is a very sour soil requiring ½ oz the following winter.

Aluminium sulphate to be used only at or just before root action starts & as required during growth except when plants are set out in new position to insure acidity of new mixed compost or soil. (Alkaline soil waters in new position may poison plant before it starts).

A compost can be used with a newer dung. I sometimes use a very heavy liquid manure that would destroy a plant where Aluminium sulphate is not used. This is to produce large flowers. On indicas a semi-double rose that had 1½ inch fls when I received it, each year the fls are larger. In the third year some fls 3½ inches - not one under 3. Aluminium sulphate only was used after in repotting 3rd year with a richer dung. Aluminium sulphate acts in 2 to 4 weeks after application depending on volumes of water used to carry same through root system. Therefore I like to apply in small dose & often as required, growth is under your control - (Apparently the chemical action washes away soon, not prolonging growth too late, & above all assists in ripening wood, stimulating roots and uses all food available at the time in soil).

The use of phosphorus & potash applied round the edge of the ball of roots gives more available food if applied not later than mid May. No better food exists than potash to ripen wood - however this is not necessary but will without doubt bring seedlings into flower years sooner. I believe aluminium sulphate alone will increase the well being of Rhodrn many times. Salt delays the decomposition or breaking down of leaves, dung & waste - along Coast material holds its color for years ! ! !

Respectfully yours,

Commentary: This letter on its own, as originally written in longhand with all the abbreviations, does not make easy reading and the contents require careful interpretation. However, the correspondence fits in well with a letter written by James Barto to Joseph Gable dated July 8th, 1932, and when read together they are quite thought-provoking. The letter to Mr. Magor contains Barto’s methodology for the use of salt, aluminium sulphate and the quantities required; whereas the correspondence with Gable explains Barto’s case study and his reasoning for the application of these chemicals during cultivation at the homestead. The following two paragraphs have been extracted from the letter to Gable:

It is developing my trade as a carpenter took me to the outposts of settlement. The coast and high mountain areas. While at Waldport on the coast moving a house I heard of a pure white rhododendron and the next season discovered this plant. According to Wilson it is the missing species reported by Menzies over 150 years ago. Also in Alsea Bay the salt spray carried overhead and falling as rain tasted brackish. Rhododendrons lived in it all around. Every house here had its boat tied to the porch in preparedness for the ever expected tidal wave which inundated this town periodically. All this site is a wonderful rhododendron area. Therefore salt is a good thing for rhododendron californicum (macrophyllum) and also I believe for every rhododendron in existence. A close study here show rhododendrons only grow on western slopes, facing the Pacific even if only a few yards from the edge of a bluff, along the ocean front or even two hundred miles inland. Our winds and rain from the ocean carry salt high in the air in liquid state from the storm centres at sea. The leaf mould here has not broken down, but is forming a peat colored mulch of many years harvest, and sometimes 12" deep on the west slopes and on east slopes only one third that this is a wonderful study to me and proving itself by the response of the rhododendrons that I am growing. The foliage color is all it could be and more. It is good to see growers almost gasp when entering my lath houses. I do not think the application of salt is good in the plant growing season, but in winter when nature in her moods and gales does it it cannot be wrong. I was born upstate from you and as you know a good Dutchman would not put in an asparagus bed without 2" of salt 18" below the surface of the ground. My theory is that salt adds to an acid soil and should aid as lime does to an acid soil. The doctors of science here at the Dept. of Agriculture wonder if methods of culture should not be tried, since my plants show so well.

I do not know if it customary for species to break or make more than one growth. Some have broken seven times in a single season. Rh. 'Pink Pearl' made 24" in two years from cuttings, breaking time after time with over 18 branches. It may be the salt and aluminium sulphate in conjunction with ripening of the wood by withholding water that is doing it. Of course, I spray them on the foliage as orchids are done, and there almost seems to be a link with spraying orchids in this spraying the foliage.

There remains a problem that needs to be resolved. Whilst exchanging information with Jay Murray, A.R.S. Plant Registrar, in respect of plants that are known to have originated from the Barto homestead, an interesting fact came to the attention of the author. In regard to the registration of R. 'Fair Sky', an R. augustinii seedling raised by Barto, the International Rhododendron Register notes, "Seed from the James Barto Expedition 1924." We can but wonder if Barto, against all the odds, took part in an expedition just a few years after arriving in Oregon, but this does not correlate with Mrs. Barto's comments to Del James that her husband had never travelled to foreign lands in search of rhododendrons. A more logical explanation would be that the I.R.R. notes contain a transcription error and that the seed was given to Barto by Mrs. Berry and it came from the 1924/25 Rock Expedition that included #10937 R. augustinii var. chasmanthum . A flower description of this species reflects that for R. 'Fair Sky'.

In Conclusion

Ernest H. Wilson and his wife Nellie were returning to their South Street, Boston, home from a visit to their daughter in Geneva, N.Y. State, on October 15th, 1930, when their car spun off the road and dropped forty feet down an embankment near Worcester, Massachusetts. Nellie was dead when she was pulled from the wreck and Wilson died of his injuries an hour later. Tragically, this highway accident brough to an end the key role of facilitator that Wilson had played in this story since the turn of the century.

The impact of WWII on the "North American Triangle" is all too evident from a comment in a letter (now in the care of the Lane County Museum, Eugene) from Barto to Mrs. Chauncey J. Craddock of Eureka, Northern California:

The war in Europe has cut off my supply from Mr. Magor and others. But the results are beginning to show in the hybrids starting to flower, crossed some years ago... A hard freeze on the first May, 1939, destroyed many of the terminals... I am waiting patiently for the Falconeri and Lacteums to come in flower the plants are growing fine but some of these years I hope for my reward... Recent illness demands I get a lots of rest so I will close... This letter is undated but WWII did not have the major impact indicated by Barto during the early months of hostilities so it was probably written in the spring of 1940. This was shortly before he became very ill and sought admission to the Veterans Administration Hospital in Portland, Oregon, where he was admitted for medical care in May 1940. Sadly, he was found to have cancer and never returned home to see his Rhododendron lacteum and R. falconeri plants in flower. In June of the same year the house burned to the ground and with it his library and all his records, although Merrill, the second eldest son, rescued a wooden box from the fire that contained the species file. An adjacent lath house was also partially burnt and 2,000 small plants were destroyed.

The family tried to keep the details of the disaster to themselves, but Barto persistently requested sight of his records whilst in hospital, so eventually the family had to explain the sad news to him. Merrill badly burnt his hands whilst saving the species records. James Elwood Barto passed away at the hospital on December 22nd, 1940.

The problems that Mrs. Barto faced were considerable. Almost at once the irrigation system got blocked-up completely and all watering ceased. Merrill, the only boy at home, was called up for service in WWII, and Mrs. Barto saw no alternative but to sell the plant collection, the details of which have been recorded in the articles previous referred to. Mrs. Craddock of Eureka also passed away before any detailed information about Barto could be recorded.

Around 1960 Mrs. Barto found a bundle of around fifty old letters that came from Barto's correspondents, and Pauline, his daughter, found a similar number. Dr. Carl Phetteplace reviewed the contents of this correspondence and the largest number of letters came from E.H. Wilson and Mr. Magor, both of whom wrote repeatedly and sent material. These letters also support the view that Barto received various wild collected seed from major institutions in exchange for plant material that he sent to them. Typical of this was a letter from the R.G.B., Edinburgh, enclosed with fourteen packets of species seed, including Rhododendron diaprepes (now R. decorum ssp. diaprepes ) and R. griersonianum , in exchange for a layered plant of the white form of R. macrophyllum . Merrill also indicated that his father received material many times from this source and that he prized it greatly.

The family could not locate the wooden box containing the species file, but it must have turned up later as it is said that Merrill still had the box and its contents in June 1987, the year Mrs. Ruth Lamson Barto passed away. Merrill George Barto passed away in January 1999 aged 79 and his sister Pauline Eugene Barto Sandoz died on 30th October, 2002, aged 81. With the death of Elwood William Barto of Junction City, said to be the son who helped his father in the greenhouses, on 28th June, 2003, at the age of 88, all the Barto family with direct involvement in this story have passed away. Recent discussions between Gordon Wylie and Barto's grandson and daughter-in-law confirmed that, as well as Barto's plant records and correspondence, the family's photographs and other records were also lost in the 1940 fire at the homestead. The whereabouts of the species file and the bundles of letters remain unknown; however, the grandson has promised to make further enquiries in regard to the letters.

Edward John Penberthy Magor passed away on 14th May, 1941. After her husband's death Gilian did not feel able to stay on at Lamellen and their son E. "Walter" M. Magor was then away on army service in India. So the house was let for many years and, with Britain in the midst of WWII, the garden quietly went to sleep. The eloquent words of Joseph Gable in a letter dated January 8th, 1942, to Guy Nearing, expresses the debt owed to Mr. Magor by a good many early rhododendron enthusiasts:

Well our good old friend Mr. Magor has passed on and I am sure if rhododendron lovers had any share in building up his future reward in the life to come he would not want. Letters from Australia, New Zealand, Chile, Japan and Germany that I can recall, all praised him for his disinterested generosity in helping them to obtain their wants. That he appreciated a little of this in return I well know for he once wrote me that out of the hundreds of recipients of seed, etc. from him I was one of the few who not only thanked him but reciprocated in kind. Nothing was too much trouble for him it seemed. If he did not have the seed I wanted himself he would go fifty miles to a neighbour's garden or send to Edinburgh Botanic or to Ireland before he would abandon the effort - and then apologize - a true old English gentleman.

And I just had a Christmas note from Mr. Fraser of Ucluelet, Vancouver Island, who first introduced me - by mail - to Mr. Magor. So to these two men more than all the others - I owe my acquisitions in the first few years of my rhododendron growing.

George Fraser enjoyed his life in the small isolated community of Ucluelet and passed away on 3rd May, 1944, after fifty years of raising rhododendrons and playing his fiddle at the community dances. And, like Barto before him, Fraser's correspondence that he had carefully kept over the years was all destroyed after his death in a fire at his home. Subsequently, Gable returned sixty-two letters that Fraser had sent him and these are now preserved in the Provincial Archives of British Columbia, along with other documents resulting from research work carried out by Bill Dale of Sidney, B.C. Fraser's pioneer work with rhododendrons was acknowledged in 1991 by the post-humous presentation by the A.R.S. of the Pioneer Achievement Award.

It was the end of an era, as by the time the WWII hostilities had come to an end most of the personalities involved in this story had passed away. For two decades Mr. Magor had been the catalyst by which large volumes of rhododendron seed, pollen, scions and plants, both species and hybrids, together with detailed advice on propagation and cultivation, had found their way to North America. And, in turn, these provided James E. Barto with the foundation for much of his propagation and experimentation work. Though neither of them in their lifetime was to realise the significance of their legacy, these two pioneers were to influence and strike the imagination of later generations of rhododendron enthusiasts and gardeners across the Pacific Northwest.

In 1950 Del James suggested that a lasting memorial to James Barto be dedicated by the A.R.S.; this was eventually achieved through the presentation in 1995 of the Pioneer Achievement Award. It is unfortunate that E.J.P Magor's contribution to the international dissemination of rhododendron plant material and knowledge has gone unacknowledged for so many years. Heading this article is the inscription, very appropriate in respect of both these pioneers, that adorns the tomb of Sir Christopher Wren in St. Paul's Cathedral, London.

Joseph Gable passed away July 21st, 1972; he had been blind for three years and partially-sighted for many more. Correspondence between Gable and Nearing, and vice-versa, together with other records, are preserved in the Alderman Library of the University of Virginia as a result of research work led by the late George W. Ring of Bent Mountain, Virginia. Gable was posthumously presented with the Pioneer Achievement Award by the A.R.S. in 1982.

And, what happened to Lamellen? Major E. Walter M. Magor returned in 1961 from service in India and South Africa to live at Lamellen and he commuted weekly to London until he retired in 1971. Sadly, his wife Daphne passed away a year later at the young age of 56, having spent a decade restoring the house and garden. Walter continued to pursue his gardening interests in the same benevolent way as his father, and many major gardens in Great Britain and Ireland have reason to be grateful for the help and advice he provided.

Felicity, his eldest daughter, came to live at Lamellen in 1974 with her husband Jeremy Peter-Hoblyn, another Cornishman. Walter passed away in 1995 leaving Felicity and Jeremy to continue restoration work at Lamellen, so the garden remains in the care of the Magor family.

And what of Lamellen garden itself? Well, little has been said about this peaceful, atmospheric and beautiful garden; but perhaps that's another story.

References

Barrett, Clarence "Slim." 1990. The James Barto farm revisited.

Journ. Amer.

Rhod. Soc.

44 (2): 73.

Barto, James E. 1936-1940. Correspondence & photograph. Lane County Museum,

Eugene, OR.

Burns, Frances Scharen. 2001.

To Have a Friend. An Exchange of Letters on

Rhododendrons, Iris, Lilies, War and Peace 1945-1951. Del & Rae James and C. P.

Raffill

. Big Rock Press, Vida, OR.

Dale, Bill. 2000-2003. Correspondence with the author and copies of articles

about the life of George Fraser.

Henny, Rudolph. 1960. Five Letters From James Barto to Joseph Gable.

Quart. Bull.

Amer. Rhod. Soc.

14 (4): 220-231.

Holaday, Joseph A. 1992. The Barto Rhododendron Nursery: A Personal Recollection.

Journ. Amer. Rhod. Soc.

46 (2): 93-94.

James, Del. 1950. James E. Barto.

Quart. Bull. Amer. Rhod.

Soc. 4 (2): 60-63.

Magor, Edward John Penberthy. 1901-1941. Lamellen Estate records, including ledgers,

scrapbooks, old Family documents and photographs.

Magor, Walter. 1985. Lamellen.

Cornish Garden

. March, 1985: 14-19.

Phetteplace, Carl H. MD. 1961. The life and work of James Barto.

Quart. Bull. Amer.

Rhod. Soc.

14(2):66-73. 14(3) 147-153.

Shephard, Sue. 2003.

Seeds of Fortune, a Gardening Dynasty

. Bloomsbury, London.

The Register Guard

, 1987-2003. Obituary & deaths archives. Eugene, Oregon.

Van Veen, Ted. 2003. Correspondence with the author about Theodore Van Veen and

James Barto.

The author is particularly grateful to Jeremy and Felicity Peter-Hoblyn, Lamellen, Cornwall, who answered a plethora of queries and provided access to fragile ledgers and old family documents from the Estate records during research work to unravel a number of matters relating to E.J.P. Magor and the development of Lamellen garden. The author is also very grateful to Gordon Wylie of Eugene, Oregon, who has made numerous enquiries, including making contact with the surviving grandson of James Barto, who resides on the property at High Pass Road, in a search for old photographs of the homestead.

John Hammond, a member of the Scottish Chapter, authored the recently published article "The Lost Rhododendrons of Townhill Park, Southampton, England," which appeared in the Summer 2003 and Fall 2003 issues of the Journal.