JARS v59n3 - Colonsay House Gardens: Kiloran: Isle of Colonsay, Argyll, Scotland

Colonsay House Gardens: Kiloran:

Isle of Colonsay, Argyll, Scotland

An historical perspective of the development of the

Gardens of Lord Strathcona and Mount Royal and their "connections" with North America

John M. Hammond

Starling, Lancashire, England

Scotland's West Coast gardens have provided inspiration to generations of rhododendron enthusiasts and each year the approaching spring awakens those now familiar yearnings to return to the West Highlands and Islands of Argyll. And yet, inexplicably, relatively few enthusiasts take time out to visit one of the most impressive and historically significant gardens in the region.

Lying off Argyll's rugged coastline, just to the north of latitude 56˚00' and to the north-west of the Isles of Islay and Jura, with only the Atlantic between it and the shores of Labrador, is the Isle of Colonsay. Little wonder that the Atlantic gales provide the driving force that pounds the high seas against the cliff faces on the island's western flanks, sending clouds of salt-laden sea-spray well inland.

Caledonian MacBrayne's strangle-hold on the ferry services to the Isles are as much a part of the folklore as any aspect of life in these parts. Services operate out of Oban's natural harbour, also from the West Loch near Tarbert on the coast of Kintyre, and provide a spectacular scenic journey as they wind in and out of the Isles against a mountain backdrop still covered with snow in the early spring. Arrival at the Scalasaig jetty on the relatively protected eastern shore is a stark introduction to the rigours of creating a garden on a virtually treeless island. With barren moorland stretching as far as the eye can see Colonsay is considerably more exposed to the elements and enjoys about 47 inches (117.5 cm) rainfall, around half the average of other West Coast gardens. Yet Colonsay remains temperate on account of the Gulf Stream's influence that tends to ensure the winter temperatures remain relatively mild, but there is an abiding need for shelter from the persistent south-westerly and north-westerly winds.

A straight single-track road gradually becomes visible from the ferry, climbing away from the jetty to the Isle of Colonsay Hotel, with short access roads diverging to the scattered cottages which comprise Scalasaig. As the ferry approaches the shore the small community comes to life as pedestrians and vehicles slowly appear as though summoned by some in-built time call. Straightaway one gets the feeling that time is not a particularly important aspect of life in these parts. Climbing northwards out of Scalasaig the meandering road crosses the highland moors where a myriad of clumps of yellow iris flower in June, then zig-zags around Turraman Loch and Loch Fada as the single-track carriageway skirts the north side of the island.

But nothing can really prepare the visitor for the view as the car breasts the top of a wild moorland summit to see a wide expanse of mature woodland opening-up in the sheltered valley beyond Kiloran. In the midst is the long, low and white-walled Colonsay House. Soon the wild moorland gives way to hybrid rhododendron bushes planted alongside the road with a backdrop of massive beeches ( Fagus sylvatica ) and oak ( Quercus penunculata ) trees and plane ( Platanus x hispanica ) trees which provide a canopy over the garden itself. There are indications of the early plantings of Rhododendron ponticum as a shelter belt, some of which has escaped onto the moor in relatively recent years, the result of seed carried on the wind. More significant shelter is provided by larch ( Larix deciduas ), Sitka spruce ( Picea sitchensis ) and also the incredibly fast growing Monterey pine ( Pinus radiata ) with its ornamental bright green foliage.

On passing through the entrance gates, and moving slowly down the main drive, that sense of timelessness, that was all too pervasive on landing at the Scalasaig jetty, becomes enmeshed with the feeling that there is much of historical significance here. So, on arrival at the House, it is no surprise to learn that its history and that of the garden are deeply intertwined with the island's troubled past.

St. Columba, Colonsay and Iona

Colonsay takes its name from St. Columba who was banished from Ireland after taking up arms and defeating the High King of Ireland in battle at Culdrevney in Co. Sligo in the 6th Century. St. Columba and twelve of his followers departed from their homeland to seek refuge on Scotland's West Coast, establishing a monastic order on the Island of Oronsay, named after St Oran, that is accessible from the southern coast of Colonsay at low tide across "The Strand."

Looking seaward from Oronsay on a clear day the hills of north-western Donegal stand out on the southwestern horizon and it is said that St. Columba was troubled by being able to see his beloved homeland where he was born in 521. So in 563, leaving some of his followers at Oronsay Abbey, St. Columba moved on up the West Coast and established the monastic settlement on the Island of Iona. He died on Iona in 597 but his name remains synonymous with that of the Isle of Colonsay. Records suggest that an abbey was constructed at Kiloran by St. Columba in honour of St. Oran and a graveyard was established close by. Vikings from Scandinavia raided the Western Isles before the end of the 8th Century; the pagans pillaged Iona three times between 793 and 806 before moving south to attack Colonsay, Islay and Jura. The "say" ending of Colonsay is of Norse origin. Both Colonsay and Oronsay frequently changed ownership in the ongoing battles for the throne of Scotland and the Wars of Independence with the "Olde Enemy," England; a situation more even more complex by the persistent skirmishing between the Clans McPhee, McDonald, McLean and the Campbells. The latter came down in force in 1639, carried off everything they could lay their hands on and the islands became a Campbell possession.

In March 1701 Colonsay and Oronsay were sold by the 10th Earl of Argyll, Chief of the Campbell Clan and later to become the 1st Duke of Argyll, to Malcolm McNeill who was married to Barbara, daughter of Campbell of Dunstaffnage. Stones from the ruins of Kiloran Abbey are believed to have been used by Malcolm McNeill for building the older part of Colonsay House, the main centre block, on the site of the abbey in 1722. Little is known about his son Donald who inherited it on the death of his father in 1742. Donald's son Archibald inherited it on the death of his father in c. 1772.

|

|

The rear of Colonsay House

looks directly out across the expansive lawn that

runs down in tiers to the stream. Bounding the lawn is a wide selection of trees and shrubs, including palms and Cuppressus macracarpa . Photo by John M. Hammond |

Colonsay and its North American "Connections"

Archibald McNeill is remembered as a popular laird and his career was not confined to Colonsay. It is believed that he was on the staff of Lord William Campbell, a brother of the 5th Duke of Argyll, who was Governor of the American Colony at the outbreak of the War of Independence in 1775. Local tradition on Colonsay indicates that Archibald was Governor of South Carolina. He later raised the 3rd Argyll Fencibles in 1799, commanded them as Colonel and the regiment was garrisoned at Gibraltar from 1800 to 1802. Around 1790 he extended Colonsay House, adding the two curved wings that partly encircle the main approach to the house. Archibald's military campaigns are said to have severely affected him financially and he sold Colonsay to John McNeill, his first cousin, in 1805. John McNeill was Laird for forty years and he made Colonsay prosperous again. He laid out the road network, constructed the original Scalasaig pier and is still fondly remembered with affection as the "Old Laird."

Unfortunately, the prosperous conditions took a downward slide after the death of the "Old Laird" in 1846, which was also the year of the potato famine. Potatoes were the stable food on the island from c. 1740 and considerable quantities were exported. But the potato crop failed entirely, not just for one year but for several years in succession. As a direct result of the famine the living conditions of the islanders deteriorated comparatively rapidly and the majority of the tenants emigrated en-masse to Canada in 1852. Records suggest they arrived in the St. Laurence in a very poor health a direct result of their state of distress and starvation when they embarked on the Clyde. According to John McPhee, whose great-grandfather left Colonsay with the emigrants and became a miner in Ohio, most of the families who survived their ordeal crossed the border and diffused into the American interior and prospered in all sorts of professions.

At this time the island itself was also a "waiff in the storm." Alexander, the eldest son of the "Old Laird," had inherited the islands in 1846 and sold them the following year for £40,000.00 to his brother Duncan. In turn, Duncan sold them on in 1870 to his brother John. In 1877 John McNeill sold Colonsay to his nephew John Carstairs McNeill, son of Alexander, for £80,000. 00. This figure was double the previous sale price and did not reflect the poor economic state of Colonsay at that time.

John Carstairs McNeill was a distinguished soldier who served in the Indian Army and fought in the Mutiny. He was later awarded the Victoria Cross for cutting his way, with despatches, through a force of the enemy during the Maori War of 1846 in New Zealand.

From 1869 to 1872 John Cairstairs McNeill was Military Secretary to Lord Lisguard, the Governor General of Canada, and during these years he took part in the Red River Expedition. Whilst McNeill was on this expedition it is believed that he met Donald A. Smith, then acting as Canadian government emissary. Smith had the remit to bring peace to the Red River, where there was open rebellion against plans to impose direct rule from Ottawa on both Red River and the prairies. This meeting led to a life-long friendship. In 1877 when McNeill needed financial assistance to complete the purchase of the Isle of Colonsay he turned to his friend Smith who loaned him £40,000.00, half the purchase price and something of a fortune in its own right in those days.

The Evolvement of Colonsay House Garden

All that remains of the earliest planted trees in Colonsay House garden are a few old specimens of ash ( Fraxinus excelsior ) and elm ( Ulmus glabra ), survivors of a semi-circular line of trees that marked the original boundary of the garden. Records indicate that the early plantings were painstakingly established in the early years of the 18th century shortly after the House was built. Many of the trees that survived from the original plantings only grew a few inches a year, particularly those at a higher elevation, due the winds and gales sweeping across the moorland. The first extensive plantings around the House were made early in the 19th century when five areas were planted. A few more small clusters were added in 1860. Of the deciduous trees the most commonly planted were ash ( Fraxinus excelsior ), elm ( Ulmus glabra ), beech ( Fagus sylvatica ), sycamore ( Acer pseudoplatanus ) and alder ( Alnus glutinosa ); but there are also a few lime ( Tilia x europaea ), horse chestnut ( Aesculus hippocastanum ), turkey oak ( Quercus cerris ) and white beam ( Sorbus aria ). Of the conifers, those that survived the best are larch ( Larix deciduas ), Scots pine ( Pinus sylvestris ), silver fir ( Abies veitchii ) and Norwegian spruce ( Picea abies ); but there are also a few cluster pine ( Pinus pinaster ) perhaps better known as maritime pine, mountain pine ( Pinus mugo ) and Corsican pine ( Pinus nigra subsp. laricio ).

On the south-east edge of the extensive terraced lawn stand two large specimens of the Monterey cypress ( Cupressus macrocarpa ); these were raised from seed sent in 1856 from Vancouver, B.C., by Colonel Mitchell who later served in India. They are evidently at home in the maritime climate and grew at the rate of 1 foot 10 inches (55 cm) for the first twenty-five years, which was completely different to the experience with the other tree plantings. In about 1882 seed of the Lawson cypress ( Cupressus lawsoniana ) came from the same source and proved to be the most valuable of the conifers introduced to the woodland.

|

|

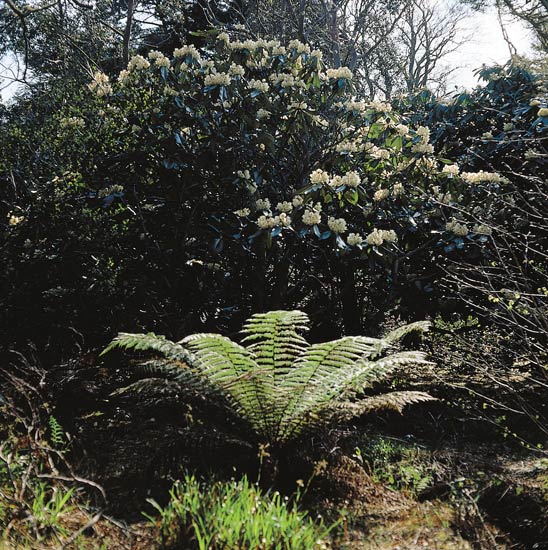

The entrance to Sino Valley

is guarded by two large plants of

R. falconeri

.

The tree fern is a reminder that a magnificent mature specimen of Dicksonia antartica stands adjacent to the Lighthouse Garden. Photo by John M. Hammond |

Rhododendron ponticum was first introduced in to Britain in 1763 from Gibraltar. In around 1850 plants were obtained from Ardlussa, on the adjacent Isle of Jura, and planted in Colonsay House garden to form a shelter belt where the woods were beginning to get thin. But its rampant growth to specimens of 20 feet (6 m) high and 40 feet (12 m) wide, and prolific seeding, enabled it to take over large tracts of the woodlands. Some tender plants and trees were devastated by the exceptionally severe winter of 1894/95, but the island normally escapes severe frosts. On the morning of 29th August 1902 the Royal Yacht set sail from Isle of Arran, steamed around the Mull of Kintyre and on through the Sound of Islay to drop anchor off Scalasaig early that evening. The morning dawned brilliant and fine for the visit of King Edward VII and the Queen who were celebrating their recent coronation. They landed at Scalasaig pier at 11.00 hrs and were met by Major-Gen. Sir John Carstairs McNeill, an equerry to the King and Queen, hence the reason for the visit. To the cheers of the islanders assembled at the harbour the royal party set off for Colonsay House where the King and Queen planted two commemorative bushes of R. ponticum in the garden. After lunch the royal party re-embarked and continued their journey north. With the passing years R. ponticum became a much maligned plant and the two bushes were cut down by the present Lord Strathcona with the agreement of Queen Elizabeth II on one of the visits of the royal yacht Britannia.

The Strathcona Dynasty and its "Connections" with North America

Sitting in the Dining Room of Colonsay House one is taken back to a bygone era and this is a reminder that the Strathcona dynasty is a remarkable story in itself. Two very large portraits in oil adorn the walls, one of which is a beautifully executed painting of the attractive wife of an earlier Earl, the other is of Donald A. Smith and is a link to a major "connection" with North America.

Donald A. Smith was born in 1820 to a family who farmed in the little town of Forres, some thirty miles east of Inverness. His parents had recently moved there from the valley of the Spey, home of their people for generations and perhaps more widely known for its whisky distilleries. Their Clan Chattan forebears fought with the Jacobite army, the "wrong-side," at the nearby Battle of Culloden; there were both Grant and Stuart relations on his mother's side, and afterwards they had gone on to develop links with North America.

At the age of 18 Smith emigrated to Canada carrying a letter of introduction to the North West Company, a major fur trading concern. Initially he carried out menial tasks at the company's Lachine warehouse, then was transferred to Goose Bay in the inhospitable climate of Labrador before emerging from the wilderness in 1869 as a major shareholder and, at the age of 40, playing a key role in the revision of the company's Charter under the name of the Hudson's Bay Company. Donald A. Smith became the first M.P. for the Fort Gary district in Manitoba, later to become Winnipeg, after being principle negotiator on behalf of the Canadian government in the resolution of disputes in this district, sometimes referred to as the Red River settlements that were then at the forefront of the settlement of the prairies. His prominent role made him a nationally known figure in Canada.

Smith joined up with the Irish-American J.J. Hill who was looking for capital to take over the St. Paul and Pacific Railroad that was in receivership. Smith contacted his Grant cousin, George Stephen who was President of the Bank of Montreal, and the two of them negotiated the purchase of the railroad. It was a major financial gamble but its success was the foundation stone of the Great Northern Railroad, the transcontinental line that J.J. Hill, "The Empire Builder," went on to complete on the American side of the border. The railroad syndicate then purchased the stock of the St. Paul & Duluth Railroad, then the western-most head of land-based communication which connected with the Missouri River complex which gave onward connection by boat to the Canadian Mid-West.

Shortly after Donald A. Smith and George Stephen, later to become Lord Mountstephen, both joined the Canadian Pacific Railway syndicate who were responsible for raising the capital and for the construction of the tracks westward across the Rockies. It was he, aged 65, who can be seen in a wonderful old whole-plate camera photograph, a copy of which stands in the Dining Room of Colonsay House and arguably Canada's most important historical photograph, driving home the last spike on the 7th November 1885 at Craigellachie in Eagle Pass, near Revelstoke, B.C. "Hold fast, Craigellachie" was the battlecry of Clan Grant. Euan, the present Lord Strathcona and Mount Royal, re-enacted the last spike ceremony at the centenary celebrations at Craigellachie in 1985.

Unfortunately, the Colonsay Estate was not particularly remunerative during the years that John Carstairs McNeill was Laird and Donald Smith's loan was never re-paid, a source of much embarrassment to McNeill up to his death in 1904. He was unmarried and none of his family was prepared to purchase the Estate, so the sale of the Estate became a necessity to meet the liabilities. In the aftermath of the death of his friend, Donald Smith agreed to purchase the Colonsay Estate and some other securities, including American railroad bonds, from the executors for £44,000.00 of which £40,000.00 was the other half of McNeill's original purchase price, thus settling the bad debt.

Donald A. Smith left a huge house in Montreal and returned to Great Britain in 1896 as the London-based High Commissioner for Canada. He received the title of Lord Strathcona and Mount Royal, bought a 64,000- acre estate in Glencoe and built a massive mansion in its own grounds in the likeness of a Canadian Pacific Railway hotel.

This prominent politician, senior Hudson's Bay Company official, Director of the St. Paul & Pacific Railroad, Director of the Canadian Pacific Railway and a Director of the Bank of Montreal, is said by the family to have made and parted with several fortunes in his long and eventful life. A man of great vision, who displayed tremendous perseverance in the face of personal adversity, was an extremely shrewd businessman in many walks of life and was endowed with a considerable determination to get things done. These notes provide but a glimpse of a person of whom three biographies have been written.

At the age of 87, when he was already chairman of many companies including Burmah Oil, he was made the first Chairman of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Co., later British Petroleum, and persuaded his young friend Winston Churchill to get the government to take a major stake to protect oil supplies for a Naval Fleet converting from coal to oil power.

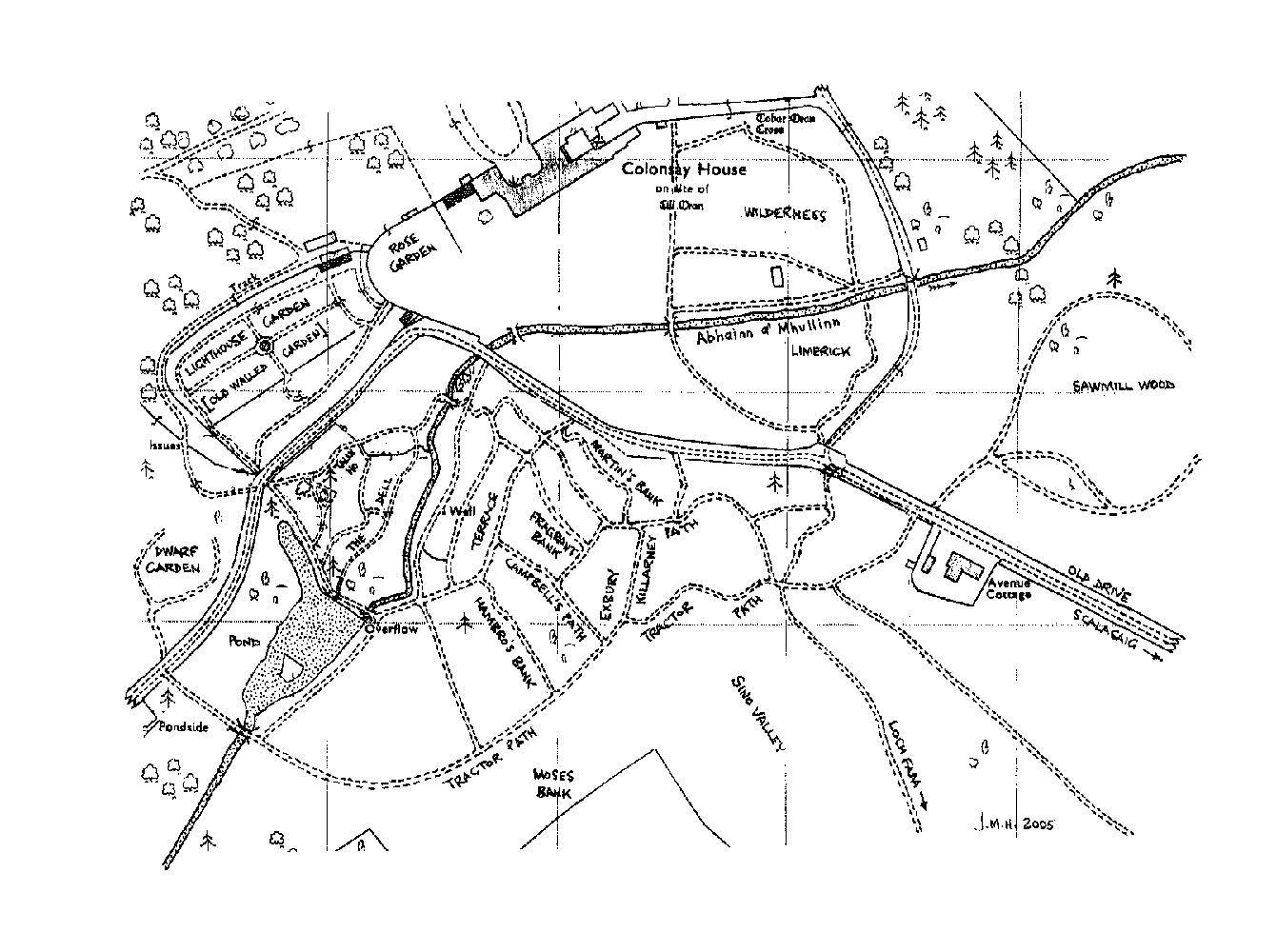

|

| Map of the Garden at Colonsay |

The Development of Colonsay Garden

Lord Strathcona added two floors of bedrooms to Colonsay House shortly after acquiring the Estate to enable him and his entourage to visit the island for a month each a year on a chartered yacht. Lord Strathcona was as rich as any man could be at this time, with homes in Winnipeg, Montreal, Nova Scotia, London, Essex, Glen Coe and Colonsay. He died in 1913 and is remembered by a stained glass window in Westminster Abbey, London, and for helping to finance the construction of major public buildings and universities on both sides of the Atlantic.

There are many parallels which can be drawn between Donald A. Smith's vision and determination to get things done and the accomplishments achieved a couple of generations later in the creation of a woodland garden of major proportions in years between 1928 and 1939. This being after Donald, the third Lord Strathcona and Mount Royal, inherited the title and returned from India in 1926. He quickly disposed of the huge Glen Coe Estate, and made Colonsay House the family residence.

Inspiration to develop the gardens came from Donald's father-in-law Sir Gerald W.E. Loder, later the 1st Lord Wakehurst, who took his title from his Sussex home having spent a lifetime creating a garden around it. Sir Gerald recognised the horticultural possibilities that were ably demonstrated by the growth of Rhododendron ponticum . He suggested it presented an opportunity for the clearance of large pockets out of the stands of R. ponticum , but leaving sufficient behind to form a substantial hedge thus forming protected areas in which to grow a wide variety of both tender and hardy plants. John De Vere Loder, Sir Gerald's only son, greatly enjoyed his visits to the island and wrote the definitive history of Colonsay and Oronsay that was first published in 1935. Valuable encouragement to develop the gardens also came from F.R.S. Balfour of Dawyck.

Clearing, draining, path-making and planting commenced in 1928 and up to twelve gardeners worked under the sage direction of Murdock McNeill, an islander who had been trained at the R.G.B., Kew. It is well worth pausing for a moment to consider how this work was carried out. At this time there was but one tractor, no mechanically propelled road vehicles or mechanically driven plant equipment, on the island. So, all building, forestry and clearance work was carried out by manual labour and transport of material was by horse and cart. This approach fitted in well with Lord Strathcona's policy of finding employment for the islanders in the difficult economic climate of the late-1920s and early-1930s, but creating a major garden amidst a sea of rocky outcrops with poor accessibility and very shallow topsoil was an extraordinarily difficult task. Prior to the construction of a new pier at Scalasaig in 1965 all supplies or passengers from the mainland, or from other islands, had to be trans-shipped off-shore from the steamer to an open boat, irrespective of the weather.

The garden is composed of about ten separate areas that were progressively developed as the garden evolved. At this time the overlay of rather shallow soil had not in any way deterred the rapid growth and spread of the R. ponticum shelter belt, into which large bays were cut to accommodate new plant material as the frequent consignments arrived by ferry. Shipments of smaller plants arriving at Scalasaig were taken to the Walled Garden, close to the House, and part of this area was set aside as a nursery where the plants could become established, then moved sometime later and planted in their permanent location. Larger plants were planted out in the garden immediately on arrival.

The initial plantings in late-1930 were aimed at creating an impressive display at the entrance gates, alongside the drive to Colonsay House and also on a mound on the far side of the pond to reflect in the still water. Batches of well known hybrids, such as the popular Rhododendron 'Pink Pearl' and the Waterer's cross R. 'Monstrous' with large pink flowers, were used along with species such as R. hodgsonii . It seems the mound behind the pond was the most successful of these early plans and the following year gunnera, rodgersia, agapanthus and yuccas were added along the sides of the pond.

Embothriums, acers, magnolias, eucryphias and eucalyptus were also established at this time but in no way were the new plantings intended to become a simple collection of rhododendrons and complementary trees and shrubs. These new developments were aimed to be in keeping with the formal and showy tradition of a past age of country house gardens. Maximum use was made of tender and unusual plants that would thrive in the temperate climate; these include Olearia semidentata , Myrtus luma , Pittosporum tennifolium and Senecio rotundifolium . Fuschias, ferns, hoherias and callistemons were also widely planted.

Whilst this work was in progress Lord Strathcona was wrestling with another problem. It was possible for visitors staying at Colonsay House to gain access to the area being developed around the pond by using a track that passed around the back of the walled garden and then by taking a short walk along the Old Drive. But the pond itself was relatively close to the House and somehow there needed to be a walkway through the woodlands to complete the connection with the semi-formal terraced lawns to the rear of the House. The solution came in the form of instructions to his Head Gardener in the winter of 1931/32. "Clear ground in the gully below Pond to form a Dell for rhododendrons. Cut down the large trees marked. Leave most evergreens and conifers. Dig out the ground to a depth of at least two and a half feet and treat with good soil and leaf mould." One thing that Murdoch McNeill was never short of was a plan of work!

Lord Strathcona's approach made use of the out-fall of the pond that, after running through the newly created Rhododendron Dell, would resume its journey along the bottom of the terraced lawns. A new pathway was constructed that dropped away from the footpath around the pond and wound its way down the Dell to the Old Drive, from which another new path gave access to the shrubbery area at the bottom of the lawns. With a view to providing flowers over a long season great care was taken with the choice of rhododendron species and other plants to be put in the Dell.

By 1934 over one hundred rhododendrons had been initially planted in the Dell, including Rhododendron oreodoxa , R. calophytum and R. sutchuenense for early flowering, R. thomsonii , R. falconeri , and R. sinogrande for the main season and R. auriculatum , R. diaprepes (now R. decorum ssp. diaprepes ) and R. kyawi for their late flowers. Tender plants were grown against the rock faces and walls, such as R. megacalyx , R. bullatum and R. crassum (now R. maddenii ssp. crassum ). On completion of the initial work in the Dell a tally of the remaining plants in the nursery showed the beds still held 274 plants. This listing alone would have formed the basis on which to build a major collection.

|

|

R. venator

provides a glorious splash of scarlet-red.

Photo by John M. Hammond |

In the three years prior to 1932 the accession lists that Lord Strathcona meticulously kept show that he had been able to obtain almost all of the species that were in cultivation in Britain in the early 1930s and around a third were Forrest introductions. Little wonder that by 1932 all the space was taken in the existing nursery beds and that new beds had to be created. Many of these plants came from friends of the family such as the Balfour's at Dawyck, the Stirling Maxwell's at Pollock House, the Loder's at Wakehurst, the Stephenson's at Tower Court and the Magor's of Lamellen. Others came from famous nurseries such as Waterers, Slococks, Knaphill, Donard's in Northern Ireland, Veitch, Gills and Sunningdale. In this way differing forms of the same species were also obtained.

Another feature which makes this garden rather unique amongst West Coast gardens is that whilst the collection of rhododendron species is wide ranging, with some most unusual plants amongst them, there is also a major collection of hybrids that probably outnumber the species by a wide margin. This garden contains a high proportion of the pedigree hybrids that were in cultivation in the 1930s, 1940s and early 1950s. Consignments originated from many famous gardens amongst which were Exbury, Bodnant, Leonardslee, Tower Court, Embley Park and Darley Dale.

But even this does not really convey the scope of the plantings, or the labour involved in the work, as some hybrids were obtained in large batches. Imagine the work involved in clearing a site, preparing the ground and planting a single order of 200 of the rosy-pink R. 'Jacksonii' from Darley Dale, a very old but one of the better early-flowering hybrids, that was used to create a hedge alongside the Old Drive. Or, planting a single batch of 120 "other hybrids" from Knaphill's on rocky virgin land with little more than a tractor in mechanical aids. Azaleas were being ordered from Knaphill's in batches of up to 200 at a time. Almost every steamer arriving at Scalasaig had consignments of plants for Lord Strathcona and, inevitably, some of were damaged en-route by salt spray and seawater. All of this work was in progress despite most of Lord Strathcona's time being taken up with his work at Westminster in the House of Lords. So his visits to Colonsay were usually restricted to the Parliamentary Recesses during the summer, autumn, Christmas and New Year, little wonder that he had an interest in late-flowering plants.

From an historical perspective a number of important personalities of their day helped in the clearance work and assisted with the new plantings. Clearance work continued at an amazing rate in 1933 in an easterly direction beyond the pool through the area later called Hambro's Bank, "where Charles Hambro cut rhododendrons." Charles Hambro, then head of the family bank, had an interest in rhododendrons, probably resulting from being directly related to Olaf Hambro who inherited the 14-acre Logan Gardens, near Stranraer on Scotland's South West Coast. Hambro was a great friend of Lord Strathcona and helped him to clear R. ponticum from along a ridge. Together they replanted the area.

During the year ditches were dug and paths were laid from the Tractor Path, on the perimeter of the work, back down the steep hillside towards the Dell. One of these new tracks became Campbell's Path when the adjacent areas were cleared, named after Sir George Campbell of Crarae who suggested the name. Another track, Killarney Path, was made by Lord Strathcona in the 1950s, the time of the National Trust for Scotland's early garden-cruise programme on the dazzling white cruise ship Lady Killarney whose draft was too deep for the pier. Crew members brought the passengers ashore in power launches and were greeted on arrival by the Laird before being taken on a tour of the garden and island. The steamer was broken up at Port Glasgow a couple of years after the commencement of the cruise programme and was replaced by the Meteor. Martin's Bank was named by the present Lord Strathcona for his eminent sailor friend Martin Minter-Kemp who helped clear a bank opposite the House. Limerick, an area closer to the House and on the opposite of The Old Drive, was named for another friend, the Earl of Limerick, a rhododendron enthusiast from East Grinstead, West Sussex, who helped clear a wet area that is still not fully under control. Some interest has recently been shown in a late-flowering, old, and perhaps long forgotten hybrid, R. 'Earl of Limerick'* ( R. edgeworthii x R. dichroanthum ) and this endangered, unregistered plant may be propagated before it is lost to cultivation.

With the incoming shipments of rhododendrons rapidly outstripping their allotted space in the nursery Lord Strathcona took time out in October 1933 to review the progress to date and to set out a timetable for the six years up to 1940. Quoting from Lord Strathcona's ledger book, "...the gardens stretching roughly from the front gates through the Dell and woodland above (i.e., south of it) to the Pond on past Murdoch's House and ultimately leading to the old kennels. The completion of this scheme and extensions in the woodland south of the area defined are limitless—must depend on 1) time and labour and 2) the creation of shelter and screens where required." Here was a man who could look at the overgrown and rocky wooded hillside, visualise what needed to be done to achieve his aims and then set down the instructions for his Head Gardener to take forward. His plan included the approach roads to the House and was in the form of a timetable for clearing, for the forming of shelter and for planting until completion.

New plantations of larch and Sitka spruce were established, well away from the garden, on the hillsides to the south and west, whilst the woodland areas closer in were thickened up with alder, birch and Monterey pine. This work continued as a priority though the initial years of the timetable as Lord Strathcona's notes show all too clearly. "The necessity for protection (against wind, salt carried by the wind, and frost and cold air) has again been demonstrated by the gales of last winter (especially the great gale of October 26, 1936) and the effect produced by some of them on trees and shrubs, especially rhododendrons."

The stands of Rhododendron ponticum , some of which had been left in lines as windbreaks, was supplemented with a variety of other shrubs, surplus old hybrids and even a batch of 100 R. griersonianum were listed to be moved from the nursery and to be planted out in the woods behind the pond. As an experiment twelve Griselinea littoralis were planted behind Murdoch Neill's house. Lord Strathcona thought the Griselinea would grow to a medium sized shrub. They turned out to be very successful and they were widely used to create hidden protective walls in the woodlands. But they were more successful than anyone could have imagined and have become 30-foot (9 m) trees that throw a lot of shade whilst breaking up the wind. And, they seed prolifically and germinate all over the place, as does Drimys aromatica .

As the years passed many of the rhododendrons quickly outgrew their original locations, as a result of the temperate maritime climate, whilst others needed to be found a more favourable site. A programme of moving plants began but this turned out to be a major exercise and all the time consignments of newly ordered plants continued to arrive, including many Kingdon Ward introductions. Such was the shortage of space that a new overflow nursery was created in Sawmill Wood, a separate large woodland area to the west of Colonsay House. In the midst of all this in September 1939 Lord Strathcona wrote, "Owing to the outbreak of war (Sept. 3) no special schemes were envisaged. Concentration was directed towards bringing more arable and garden land into cultivation for food."

Throughout all these years of major development Lord Strathcona had never seen the garden in the spring and it was to be the disruptions of WWII that brought about a nine day visit from April 23 to May 2, 1940. "Weather on the whole glorious, revealed the garden more full of flower and beauty than I have ever seen it before. Elsewhere I have made notes of the rhodos actually in flower during this period; the amount of buds about to open, especially on the different types of LODERI and FORTUNEI crosses at the top of the Dell and in the triangle was quite staggering. This immense flowering must, I think be due to (1) the very hot June in 1939 and (2) the very fine sunshine that appears to have prevailed in August and September 1939 (when I had rejoined the War and was sweltering in London docks)."

Lord Strathcona was only able to make short, sporadic visits during the war years, though shipments of plants continued to arrive, including some from Exbury gardens. But the loss of staff to the armed forces and other priorities had a major impact on the garden's continued development.

During WWII the R.A.F. had a number of posts on Colonsay due to its strategic location and they brought the first truck on to the island to provide a service over the rough gravel roads. The R.A.F. beacon at Machrins was often the first sight of Britain enjoyed by crews ferrying bombers from North America. The first "car," brought over by the Strathcona Family in 1947, was an ex-U.S. Army Jeep followed a few years later, as the roads were gradually improved by the local Council, by a van to act as a school bus. Tractors and agricultural machinery then slowly replaced the island's horse-drawn way of life.

After the war Lord Strathcona's visits resumed a more leisurely approach and the development of the garden continued, but at a slower pace in the difficult economic climate that followed the cessation of hostilities. Staff who retired were not replaced. By 1946 work on clearing and draining a natural amphitheatre alongside the track leading from the Old Drive to Loch Fada created a completely new sheltered area, at the extremity of the existing path system, that became known as Sino Valley. Instructions were given to move the Rhododendron falconeri plants in to the valley, followed by R. sinogrande and other large-leaved plants. The early post-war years turned out to be a hectic period for moving plants that had outgrown their location, or had become hidden behind other plants during WWII. A considerable amount of new planting was also done using the consignments of plants that continued to arrive by steamer. Sawmill Wood nursery was never entirely cleared of the overflow of plants, some of which had come from Arisaig, and a large number of species and hybrids were eventually found a permanent home in the wood.

Lord Strathcona's son, Euan, inherited the Estate when his father passed away in 1959 and by this date the gardens had slowly begun to decline. The financial position at the time dictated that there were many other priorities on the Estate that came before the upkeep of the garden. Gradually the woodland garden went to sleep and became overgrown, much against the wishes of the new Lord Strathcona.

By the 1980's the Estate finances had improved sufficiently for a programme of Rhododendron ponticum clearance to begin and by 1993 a substantial part of the woodland garden had been cleared. Many of the original plants were "rediscovered" in the course of the work. Over the past decade restoration work has continued at a rate dictated by the resources available. Clearance work has continued, access has been improved, paths have been re-laid, wooden bridges replaced and some replanting has been taken forward. Much of the replanting and woodwork has been carried out by Lord Strathcona himself, who has quite a reputation as a carpenter.

An area known as the Wilderness, to the south-east of the house and alongside the lawn, has been cleared and a number of interesting olearias established, including Olearia avicenniifolia , O. chathamica , O. cheesemanii , O. phlogopappa , O. rani , O. semidentata , O. traversii and O. waikariensis . Sawmill Wood, and the adjacent woodlands, remain overgrown and there are no plans at present to clear these areas. Nevertheless, the flowering of both species and hybrids each spring, amidst the sea of Rhododendron ponticum , include the J. Crosfield china rose-pink large-flowered cross R. 'Coronation Day' from Embley Park ("and no bad hybrids were ever sent out of that remarkable garden," says Lord Strathcona), a very large plant of the showy lavender-violet J.C. Williams cross R. 'Susan', the somewhat rare George Johnstone cross R. 'Saint Probus' with its deep crimson flowers, and the deep purple-red Rothschild's cross R. 'Queen of Hearts'. A number of other plants remain to be identified in this area; nevertheless, this is a reminder that the woodland garden might have been even larger but for the interruption of WWII. There is a vantage point high in the woods that looks out over Kiloran Bay, a three quarters of a mile crescent of golden-white sand, said to be the finest beach in the Hebrides.

Three key milestones were reached in 2001. Firstly, the reopening of the gardens to visitors and their subsequent inclusion in the Glorious Gardens of Argyll & Bute scheme. Secondly, Lord Strathcona's son Alexander took over the responsibility for running the Estate and with it the gardens. And, thirdly, work commenced on a grant-aided programme for eradication of R. ponticum , both in the garden and on the moorland, to alleviate concerns of it spreading further across the island.

|

|

Sea breezes permeate the woodland garden and dislodge the blooms

that gradually form a carpet along the pathways. Lord Strathcona provides a sense of scale to these bushes of R. thomsonii hybrids and R. neriiflorum . Photo by John M. Hammond |

A Tour of the Garden with Lord Strathcona

We head out through the formal Rose Garden with Lord Strathcona leading the way up to an area that was originally the Walled Garden; both areas were used as a traditional vegetable gardens in the "good old days." An olive tree can be seen in the Rose Garden where there are also some good leptospurmums, one 25 feet (7.5 m) high, and some unusual plants such as Correa backhouseana and Senecio hectoris . The enormous area encompassed by the Walled Garden was used during the 1930s and '40s as a nursery area for the smaller rhododendron plants as they were shipped in bulk from the mainland. Both these areas became overgrown and neglected in the years following WWII until, on the initiative of Lord Strathcona's wife, Patricia, they were tidied up.

The Walled Garden is now a lawned area with central intersecting pathways and bordered by shrubs and trees. The unusual centrepiece in this, the more formal part of the gardens, generates considerable interest from visitors. Here stands a massive glass Fresnell lens from a lighthouse, the lens named after the Frenchman who invented it. As Lord Strathcona explained to our group of Scottish Chapter members, the lens came from the lighthouse at the north end of the Sound of Islay when the equipment was made redundant. On leaving the Lighthouse Garden we come across the first large plants, myrtles and tree ferns, the latter from Brodick Castle garden. And inevitably, conversation quickly turns not only to the size of the plants and trees but also the propensity of the material to self-seed and germinate all over the place.

It is said that first impressions count. With rhododendrons, as with complementary plants, whilst flower colour is probably the key factor one quickly realises in this garden that considerations of size, form, foliage and hardiness complicate one's reasoning. Some plants grow so large that they are not immediately recognisable. Differing forms of the same species grow alongside each other which raises all manner of queries; the wide range of beautiful foliage types can be a distraction at times, whilst the spectacular growth of tender species so far north challenges one's perceptions of hardiness ratings.

Beyond the Walled Garden and alongside the Old Drive is the Dwarf Garden, a rocky area containing large azalea plants and acers. These azaleas came from Knaphill Nurseries, about 1934, as part of a number of larger consignments for use in various areas of the gardens. Lord Strathcona explains that this area has recently been cleared and a close inspection of the azaleas suggests that some are the remnants of a set of "Wilson's Fifty." Here too are a number of dwarf rhododendrons that have fought for survival amidst the encroaching R. ponticum and brambles.

On crossing the Old Drive we enter Pondside, the first of the ten woodland areas begun in 1928 that collectively form what has become a wild garden. Since those early days the carpet of leaves generated by each passing season has provided a more adequate overlay for all manner of plant material to grow in abundance which in turn has led to the garden's natural wild and romantic feel. And, great swaths of bluebells make a glorious show in the early spring.

One of the key features of the wild garden is the large pond whose outflow cascades through Rhododendron Dell. Around the sides of the pond are groups of azaleas, gunnera, yuccas, agapanthus and these are complemented by three large embothriums from Wakehurst, eucalyptus, acers and some magnificent magnolias which are still reaching for the sky. Amongst the latter are the large-leaved Magnolia hypoleuca , whilst M. campbellii var. mollicomata is probably a Forrest collection from north-western Yunnan and M. dawsoniana , a Wilson collection from western Szechwan Province probably came from Wakehurst.

|

|

Looking back up the pond from its outfall in to the Dell.

The trees in the

distance form the edge of the shelterbelt at the garden’s southern extremity. Photo by John M. Hammond |

But to my mind the most stunning of the magnolias are two M. campbellii which are now around 55 years old and must be all of 50 feet (15 m) tall. Lord Strathcona explained that these two mature seedlings complement each other in that whereas one is pink the other is slightly more white. Their enormous rosy porcelain-like blooms must be a sight to behold in a good-flowering spring season. This magnolia species has long associations with this area of Argyll as its seed was collected in 1849 by Joseph Hooker and named by him in 1855 after Dr. Archibald Campbell, a relative of the "Stonefield" Campbell family, who had accompanied Hooker on his Himalayan travels. As we slowly walk around the Pond there is a quick transition on approaching the out-fall as the water cascades into Rhododendron Dell, for in front of us is a host of large-leafed species in flower and enjoying the more sheltered environment. Amongst the rocky granite outcrops on the sides of the Dell are Rhododendron falconeri , R. sinogrande , R. calophytum and R. sutchuenense along with late-flowering species such as R. auriculatum and R. diaprepes (now R. decorum ssp. diaprepes ).

In the midst of the species is the tall early flowering blood-red R. 'Rocket'*, one of a number of J.B. Stevenson's crosses that came from Tower Court. This good looking R. strigillosum cross is somewhat rare and should be more widely grown, but is not to be confused with the Shammarello cross of the same name from the East Coast, U.S.A., that is available in some parts of Europe. Away to the right is a fine example of another of Roza's crosses, and undoubtedly her greatest achievement, the late-flowering R. 'Polar Bear' that has grown to major proportions. Lord Strathcona remarks that it grows well at Colonsay, needs some shelter from the wind and always flowers well, sometimes well into August and occasionally in to September.

During the course of trying to identify a hybrid we pick up a couple of sun-bleached plastic labels. "These are my unique special labels," says Lord Strathcona. “They are always illegible.” He suggests that we search for a narrow, heavy cross-section lead label, wrapped around a branch, with the name stamped in the lead. These original labels turn out to be very clear to read, have stood the test of time extremely well and gave us all something to think about in comparison with the plastic labels of more recent years.

Earlier in the year, during the planning stages for the visit, Lord Strathcona had suggested that we should come prepared with plastic bags, trowels and hand-forks as there were a considerable supply of young self-seeded species that we would be welcome to take away as mementoes of our visit. So our progress down the Dell was impeded by a number of short intermissions as one or other of the party became interested in a particular good-looking species seedling. Some were quite difficult to extract from the mat of roots caused by the competition to gain a foothold in the shallow soil.

|

|

A +25-foot plant of R. yunnanense, probably one of the largest

in cultivation,

looks out over thousands of self-seeded plants of R. yunnanense . Photo by John M. Hammond |

Given the mid-April timing of our visit we were far too early to see many hybrids in flower and these are probably at their best around the end of the first week of May. Just coming into flower on the far bank of the Dell were two enormous bushes of the Williams cross R. 'May Day', their bright red buds contrasting well again the green backdrop. Close by is a group of equally large plants of the Tally Ho Group, after which the lower part of the Dell is named. Their brilliant orange-scarlet flowers light up the area in late-June. As we clambered around the sides of the Dell to get a good look at some particularly interesting species the inevitable turning of leaves and involved discussions began as to the identity and origin of certain plants. Equally evident was the undulating nature of the woodland garden with its rocky outcrops which we carefully negotiated to access the different sections of the garden. Hambro's Bank, the Terrace, Campbell's Path, Fragrant Bank and Martin's Bank, each have their own identity and collection of plants. This, above all else, provides a sense of perspective to the single mindedness required to embark on such a project, the enormity of the task and the vision and perceptive planting needed to create such a stunningly natural garden in the midst of a bare Hebridean landscape.

Adjacent to Campbell's Path is an almost impenetrable thicket of hundreds of self-seeded species that have grown to over 6 feet (1.8 m) in height on the mossy bank, a most unusual feature that is probably unique. Close by the head of the path is the brilliant red Rhododendron neriiflorum and a group of R. thomsonii hybrids that are a stunning sight in full flower. Also nearby is the Exbury form of the May Day Group which makes interesting comparison with the Williams cross as the former has deeper red flowers, larger calyces and its growth is more compact. Half way along Campbell's Path a track diverges and leads to the aptly named Fragrant Bank where careful exploration can result in the locating of many of the Maddenia subsection that flourish in the maritime climate. Here can be found R. cubittii (now R. veitchianum ), R. lindleyi , R. dalhousiae , R. polyandrum (now R. maddenii ssp. maddenii ), R. edgeworthii and a good form of R. johnstoneanum that also grows in the lower end of the Dell.

|

|

|

|

Scattered through the woodland are several plants of

R. johnstoneanum

.

This striking example is close by the entrance to the Dell. Photo by John M. Hammond |

Close-up of

R. johnstoneanum

.

Photo by John M. Hammond |

No discussion of the rhododendron hybrids at Colonsay would be complete without reference to the collection the Loderi Group which is an outstanding feature of the garden in early-May. There is an exceptionally good pink form that arrived from Sir Gerald Loder at Wakehurst as an unnamed seedling and like others in the collection it has grown to an enormous size. These seedlings were probably raised at the Leonardslee home of Sir Edmund Loder who made the original cross. Cameron Carmichael, an authority on early-British hybrids, suggests that plant may well be the best pink form in cultivation in Britain and would be well worth propagating to ensure the form is not lost to cultivation.

On working our way down towards the Old Drive, that separates the main Woodland garden from the land to the rear of the House, there is a sizeable group of large-leaved species in the aptly named Sino Valley. These clearly enjoy having their feet in the wet spongy soil and the flowers show up well against the dark-green trees and rocky terrain. So many different species all in flower within the confines of a single valley is a remarkable sight. Evidence of wind damage could be identified on the top-most branches and Lord Strathcona remarks that some years the wind and salt-spray badly defoliate the plants. This explains why some of the plants have a slightly squat appearance, but the buds are rarely damaged and the leaves grow back the following year. Two large R. falconeri guard the entrance to the valley whilst R. arizelum , R. basilicum , R. eximium (now R. falconeri ssp. eximium ), R. rex ssp. fictolacteum and R. rex ssp. rex have grown to tree - like proportions. The latter two were grown from Rock collections.

|

|

Trusses of

R. sinogrande

in Sino Valley.

Photo by John M. Hammond |

There is also a range of different forms of R. sinogrande and these caused a great deal of good-natured debate amongst our party as to whether some of these were species or natural hybrids. Much of the debate seemed somewhat academic when Lord Strathcona confirmed that they all produced superb trusses in a good year and, after all, these particular plants had been grouped together with the intention of creating an eye - catching display, as was the case with many of the "groupings" in the woodland areas. We came to the conclusion that it may well be more instructive to take samples of both the leaves and trusses of the various forms for comparative purposes on some future occasion. Standing sentinel at the head of the valley is a superb specimen of the F.C.C. form of the Fortune Group that came from Exbury in the early 1950's, with its magnificent deep primrose-yellow trusses of around thirty flowers in bold contrast against the glossy dark green foliage.

|

|

The huge yellow trusses, with a crimson blotch, and long shiny

leaves of the F.C.C. form of the Fortune Group. Photo by John M. Hammond |

Of particular interest to many visitors are the hundreds and hundreds of young large-leaved seedlings that grow in a grove on an adjacent damp, mossy bank. These range from specimens of less than 1 inch to 3 feet in height. Out came all manner of implements as members "rescued" their choice of seedlings. I unearthed what appeared to me to be a good R. sinogrande leaf-form but only time will tell as to the viability of my 2-foot tall seedling.

|

|

On the mossy bank to the east of Sino Valley hundreds of self-sown

seedlings of large-leaved species cover the ground that Scottish Chapter members are invited to dig. Photo by John M. Hammond |

We walk back down the hillside and join the Old Drive at its intersection with the drive that skirts around the rear of Colonsay House. Looking down the Old Drive is the pink hedge of R. 'Jacksonii' and facing us in the corner of the intersection is a group of old hybrids that have grown to massive proportions. Amongst these are the white flowered of R. 'Duchess of Portland', an almost forgotten old hybrid but still one of the better whites and one that deserves to be more widely grown due to its heat tolerance. With its trunks all intertwined from multiple layering the branches of R 'Beauty of Littleworth' spread out all over the place, almost smothering a beautiful red R. arboreum hybrid we fail to find a label for. Slowly we meander down the path that leads back to the House through Limerick, another area of rhododendrons that there is not sufficient time to explore on this visit.

As we stand with Lord Strathcona beneath the ancient Cupressus macrocmpa on the edge of the lawn discussing the highlights of a day's tour around the garden, we come to the conclusion that there is never enough time to do justice to a garden like that at Colonsay House on a single visit.

There are, to my mind, many parallels that can be drawn between a visit to Colonsay House and Muncaster Castle garden in Cumbria. The accessible area of both is around 30 acres, both have major plantings that date from the late-1920s and 193Os and both handsomely repay the time spent in exploration. And, as with all intriguing gardens, there is always something else to see another day, another time.

A lasting memory of the visit, in the minds of many Scottish Chapter members, will be of a tired and happy tour-party dispersing into the inky-darkness on arrival back in the late-evening at Kennacraig Pier, on Tarbert's West Loch, with rucksacks and plastic sacks full of "trophies"; the large-leaves of R. sinogrande , R. macabeanum and other species protruding like umbrellas in all directions.

Acknowledgements

The author is particularly grateful to Euan, Lord Strathcona, who as a correspondent over many years has encouraged the Scottish Chapter to visit Colonsay, has accompanied the tour groups and the author around the gardens on a number of occasions and has provided a great deal of historical information. The Chapter is equally indebted to Lady Patricia, for her hospitality and for her tales about the family and the early years on the Island. Together they have sown the seeds that have come to fruition in this article.

* Name is not registered.

References

Gibbon, John M. 1935.

Steel of Empire, The Romantic History of the

Canadian Pacific, the Northwest Passage of Today

. The Bobbs-Merrill

Company, New York.

Hammond, John M. 1998. A Spring Visit to the Gardens of Lord Strathcona.

Newsletter, Scottish Rhododendron Society

. No.47. Autumn, 1999.

Loder, John De Vere. 1935.

Colonsay and Oronsay in the Isles of Argyll

.

New edition 1995, Colonsay Press, Colonsay House, Isle of Colonsay, Argyll.

McNeill, Murdoch. 1910.

Colonsay One of the Hebrides

. David Douglas,

Edinburgh.

McPhee, John. 1969.

The Crofter and the Laird

. Farrar, Straus and

Giroux, New York.

Strathcona and Mount Royal, Lord. Personal correspondence with the author.

Synge, Patrick M. 1955. Rhododendrons at Colonsay.

R.H.S. Rhododendron

and Camellia Year Book 1955

.

Thornley, Michael. 1988. The Rhododendron Garden, Kiloran House, Colonsay.

Newsletter, Scottish Rhododendron Society. No.13. February, 1988.

Willson,

Beckles. 1915.

The Life of Lord Strathcona and Mount Royal

.

[Vol I & II. ] Toronto.

| Ownership of Oran Abbey, Colonsay House and Gardens across the Years | |

| c563 | Oran Abbey and graveyard said to have been constructed by St. Colomba in memory of St. Oran on the site later named Kiloran. |

| c793 | Vikings from Scandinavia invaded and plundered Mull, Colonsay and Oronsay. The islands were under Norse control for the following 400 years. |

| c1200 | Clan Macdonald established by "Donald" who controlled South Kintyre, Islay and the other islands. Around this date the Macduffies or Macfies were brought by "Donald" to Colonsay from Scandinavia. |

| 1639 | After centuries of skirmishes and hostilities between the Clans the Campbell Clan plundered Colonsay and Oronsay, and took possession of the islands. |

| 1701 | Malcolm McNeill purchased Colonsay & Oronsay from Archibald Campbell, 1st Duke of Argyll. Said to have been in exchange for lands owned by the McNeills in South Knapdale. |

| 1722 | Malcolm McNeill constructed the original part of Colonsay House and garden on the site of Oran Abbey and graveyard. He planted the original ash and elm trees c.1835. |

| 1742 | Donald McNeill inherited Colonsay & Oronsay on the death of his father. c1772 Archibald McNeill inherited Colonsay & Oronsay on the death of his father and extended Colonsay House around 1790. |

| 1805 | John McNeill (the "Old Laird"), first cousin of Archibald McNeill, purchased Colonsay & Oronsay. He made the first extensive plantings of trees around the House c1825. |

| 1846 | Alexander McNeill inherited Colonsay & Oronsay on the death of his father, but had no interest in the management of the Estate. |

| 1847 | Duncan McNeill, brother of Alexander McNeill, purchased Colonsay & Oronsay. He took the title Lord Strathcona when he became a Scottish Law Lord in 1851. He made the original plantings of R. ponticum in c1850 and added more clusters of trees in c1860. |

| 1870 | John McNeill, brother of Duncan McNeill, became the 2nd Lord Strathcona when he purchased Colonsay & Oronsay. |

| 1877 | John Carstairs McNeill, nephew of John McNeill, became the 3rd Lord Strathcona when he purchased Colonsay & Oronsay. He never married. He planted further trees in c1882. |

| 1904 | Donald A. Smith, on the death of John Carstairs McNeill, purchased Colonsay from the executors of the Estate and became the 1st Lord Strathcona & Mount Royal. Donald added two floors of bedrooms to Colonsay House. |

| 1913 | On the death of Donald A. Smith his daughter, Mrs. Howard, an only child, inherited the Colonsay Estate under a "special remainder" cordially dispensed by the Crown, and became the 2nd Baron as Lady Strathcona & Mount Royal. |

| 1926 | Donald Howard, as eldest son, inherited the Colonsay Estate on the death of his mother and became the 3rd Lord Strathcona & Mount Royal. Donald created the woodland gardens. |

| 1959 | Euan Howard inherited the Colonsay Estate on the death of his father and became the 4th Lord Strathcona & Mount Royal. Euan has restored the woodland gardens. |

| 2001 | Alexander Howard, son of the present Lord Strathcona & Mount Royal, became responsible for running Colonsay Estate, including the gardens. |

John Hammond of the Scottish Chapter is a frequent contributor to the Journal. His last article "Mr Magor and the North American Triangle: An Historic Perspective" appeared in the Summer 2004 issue.