JARS v60n3 - The Gardens of Ardinglas Estate: An Historical Perspective, Part I

The Gardens of ArdKinglas Estate:

An Historical Perspective

The Campbell and Noble Families of Ardkinglas and their Development of

the Gardens, Part I

John M. Hammond

Starling, Lancashire, England

Introduction

With its reflection shimmering across the water, and its upper reaches still draped with the late-winter snows, Ben Lomond provides a magnificent backdrop in early-May as the road to the Highlands skirts the shores of Loch Lomond, some 25 miles to the north of Glasgow. Soon we leave the A82 at Tarbert and head out into "Campbell Country" on the narrow winding road that runs west to the rugged Atlantic coast. Shortly after passing beneath the scenic West Highland Railway, and circling through Arrochar village and around the upper reaches of Loch Long, the steep climb begins up Glen Croe under the watchful eye of "The Cobbler," sometimes referred to as Ben Arthur. It is easy to become distracted by the changing scenery as the A83 road climbs beyond the tree-line and runs along a cleft cut into the side of the mountain, the forest giving way to a harsh moorland mantle. Beneath us in the glen are the remnants of General Wade's Military Road built by General Caulfield's soldiers in 1748, with its zig-zag ascent near the top of the pass. In a refuge at the summit the soldiers erected a stone monument inscribed "Rest and be Thankful"” and, over the years, the refuge has lent its name to the pass, gateway to the West Highlands and Islands of Argyll.

After a couple of miles the road straightens out in Glen Kinglas and runs downhill alongside the remnants of the Military Road, with the Kinglas Water gathering speed and becoming whiter as the glen falls away to the west. By now the traffic is moving rather swiftly as the road curves away to the right and the first glimpses of the upper reaches of Loch Fyne come into view. Most gardening enthusiasts are drawn like a magnet to the scenic views around the shores of the sea-loch and make the town of Inveraray, or Crarae Glen Gardens, their initial point of call. And, in doing so, they have unknowingly bypassed one of Argyll's oldest, mature and most beautiful gardens.

So, let's retrace our steps and take the road signposted "Cairndow" that diverges to the left at the end of the long straight, which runs parallel to the Kinglas Water. Suddenly, we are in another world. This road, a segment of the original carriageway to Inveraray, runs steeply downhill with a mature tree canopy overhead. There's but a glimpse on the right of a gateway and a crofter's cottage surrounded by rhododendrons in bloom, and then shortly after we take a sharp left turn though the entrance gates and come to a halt in Ardkinglas Woodland Garden.

Scotland's western seaboard "enjoys" many days of mists and rain, with occasional considerable gales from the south-west and very infrequent severe storms of hurricane force from the north-west. The temperate marine climate offsets the chance of severe frost and at sea level the area is virtually immune from snow. Accordingly, the seasons are not clearly defined, and growth is possible almost all year round. Located 40 miles inland, with its back set against the mountain barrier, Ardkinglas has an average yearly rainfall twice that of Kintyre's rugged Atlantic coast. Fifty years ago the average was 120 inches, but today it is closer to 100 inches.

In historical terms it is difficult to segregate reality from legend in regard to the Campbell Family whose control of the un-populated wild expanses of Argyll, and beyond, made the clan a powerful force to be reckoned with. Down the centuries the continual skirmishes within and without the clan, coupled with a general disdain of authority, made the Campbells a thorn in the side of governments on both sides of the Scottish Border. Those of the Family who chose to become involved in the murky and treacherous world of politics and religious reformation often paid a high price. And, it is against this background that the development took place of the parkland, woodlands and gardens that surround the many castles and houses of the Campbell Family. Several years of research have uncovered a multitude of snapshots relating to Ardkinglas, each a glimpse of some aspect of its past, but no cohesive account of its fascinating history has been previously written or published. There are many conflicting dates and erroneous reports that have been repeated down the years in various publications. Through reference to wider historical material, this article seeks to establish a different perspective and a more realistic time-line that corresponds with what is known about the other key personalities in this story.

The Origins of Ardkinglas

On Innis Chonnell, an isle at the southern end of Loch Awe, stands the ruin of its namesake castle, stronghold of the Knights of Lochow (Loch Awe). This castle, said to date from the 12th century, was the traditional home of the Head of the House of Campbell.

The ancient lands of Aird Achoinghlaiss (Abode of the grey dog) first appear in recorded history in 1396 when Sir Colin Campbell, 13th Knight of Lochow, granted the lands to his 2nd son Caileen Org: "...in all its righteous heaths and marches, with the Patronage of its Churches and Chapels, in all its hawkings, huntings and fowlings, etc., and that for as long as the woods should grow and the waters flow from that year to next year and so on for ever..."

This wonderful poetic interpretation from the Gaelic by Niall Diarmid Campbell (1872-1949), Curator of Ardkinglas, is typical of the lilt of the Charters of the Middle Ages whose content retains a clarity of expression that has not been bettered down the centuries by the legal fraternity (1). This grant of lands also records that the House of Lochow had possessed the lands for a least a century prior to 1396. Thus Caileen ("the Younger") Org became Colin Campbell (d. 1434), 1st Laird of the House of Ardkinglas and married Christina MacLagman of Lamont in the same year. The feudal condition attached was the provision, by the new family at their own expense, of two war galleys, one of eight oars and the other of six, to serve the Lord of Lochlow or the King of Scotland, in times of war and tumult. Subsequent history shows only too clearly that this rent was fully paid. The lands at this time were very extensive, virtually treeless, and covered as far south as Dunoon, the church at Lochgoilhead being the burial place for the House of Ardkinglas.

As to the location of the original residence of Ardkinglas, history is silent. Sir John Stirling's, The Statistical Account of Scotland, of 1792, notes: "...The old residence of the family of Ardkinglass, of which the ruins can now scarcely be traced, was at a small distance from the present castle but in a more commanding situation."

A site that reflects this account can be identified on top of the ridge, immediately to the rear of the present Walled Garden, that is located to the north north-east of the position of the old castle. At this site, but at a slightly higher elevation, are the remains of a massive stone-lined tank or well. Aird generally means the abode (residence) of a great family; the abbreviated form Ard also means high and, in former times, powerful families usually built in high positions. As to the castle that Caileen Org subsequently built on a triangle of relatively flat land at the mouth of the Kinglas, little is written. From the account by Sir John Sinclair, together with other sources, we know that the massive walls of the castle formed a square enclosure and all corners, except that to the west, were defended by three round towers (2). In the centre of the southwestern wall a projection formed a massive gate-house with small round turrets at each side and a large defending tower over the arched gate. Inside the square courtyard, measuring around 98 feet in each direction, there were ranges of buildings set against the outside walls for stables, storehouses, cellars and servants quarters. The castle stood where the field gate of the present footpath across the "Park" intersects with the driveway as it curves at a tangent towards the main entrance of the present House.

The Origins of Inveraray

Sir Duncan Campbell, eldest son of Sir Colin Campbell (13th Knight of Lochow), was created Ist Lord Campbell by James II in 1445. On the death of Duncan in 1453 his grandson Colin (d. 1493) became 2nd Lord Campbell. He was created 1st Earl of Argyll in 1457 and in 1477 moved the Family home from Innes Chonnell to Inveraray on Loch Fyne, where a new castle was constructed in the form of a tower house. The 8th Duke of Argyll, in 1896, in giving evidence before a Committee of the House of Commons on a projected railway to Inveraray, stated that the narrow border of level land there, between the mountains and the sea, had been continually planted by his family for 400 years. This suggests that the original plantings at Inveraray were amongst the earliest in Scotland, commencing not long after the 1st Earl of Argyll moved the Family home to Loch Fyne.

On 9th September, 1513 John Campbell, 4th Laird of Ardkinglas, joined Archibald, 2nd Earl of Argyll, on the right-wing of the Scots army at the Battle of Flodden. Both perished on the field, along with most of the chiefs of the clans in their division, their bodies being carried overland to Dumbarton and then north by galley up Loch Long and Loch Goil. Niall Diarmid Campbell writes: "...His reliques (John Campbell) were borne homewards by his vassals, with great solemnity and laid with those of his forefathers in the Chauntry Chapel of Lochgoilhead...as the old record touchingly has it ‘they deyit valiauntlie fechting togidder'"(1).

It is not generally realised that the lochs, sea-lochs and the open sea around the Highlands and Islands formed the main communications medium for the extended branches of the Campbell Family. When hostilities arose they were a daunting enemy in naval engagements and a record exists of a major sea-battle with the English Navy, just off the Isle of Gigha, when many Campbell galleys were sunk.

Many of the wider Campbell Family were drowned at sea including Sir Iain Campbell, 7th Laird of Ardkinglas, whose deeds are legendary, and he was arguably the most ferocious laird of the entire Campbell dynasty. In 1615 his galley capsized whilst returning home from the sacking of the Isle of Rathlin after carrying out a "commission" by the King to exterminate the MacGregor clan. His son Colin, who was also manning the galley, was saved and became the 8th Laird. Hostilities were not the only cause of death; some died when a sudden storm hit the Campbell galleys whilst they were at sea. At this time there was no carriage-way north of Dumbarton, 40 miles south of Ardkinglas on the Clyde estuary, so the majority of supplies came by sea. Thus the Lowland merchants arrived in their boats at Inveraray to sell and trade produce. Building materials were transported by boat, as was the iron and other supplies required for warfare.

The earliest horticultural reference can be traced back to c 1630 where a writer found at the Earl of Argyll's "Pallace”: "...zairds (gardens) planted with sundrie fruit trees verie prettily sett...there is one Castle on the south side of this Lochfine called Ardkinglas having fair yeards planted with sundrie kinds of fruit trees therein, and sundrie kinds of herbs" (4).

By 1650 there was a designed landscape and garden around Inveraray Castle, said to be the work of William Boutcher, and the lime avenue on the south side was probably planted around this time.

The years 1638-1660 were the most turbulent in British history and Ardkinglas had in Sir James Campbell, the 9th Laird, a man to match the times. Niall Diamid Campbell picks up the story: "...Sir James 9th Laird whose life was one long record of tumultuous war, raid and foray. In 1645 he was amongst those who escaped from Inverlochy where forty Campbell lairds lay slain. In 1646 he was defeated at the Battle of Callendar, when 1,200 of his own vassals were with him, by the men of Atholl and Inchbrakie. In 1654 he was cited before the Privy Council by Sir James Lamont of Inveryne for his murders of many of the latter clan. In 1661 he was indicted for murder by Sir John Lamont of Inveryne and on 3rd September 1662 following on his being declared a Fugitive and a traitor, the Lyon King at Arms and his heralds clad in their tubards passed with trumpeters from the Houses of Parliament to the Market Cross of Edinburgh, with the Arms of the traitor Ardkinglas blazoned on paper and affixed them to the Cross backwards and then did rend them in sunder to the sound of trumpets. He was never restored to his honours and barony but his eldest son Sir Colin 10th Laird at the intercession of the 9th Earl of Argyll was fully restored in the year 1665..." (1).

Sir Colin Campbell (d. 1709), 10th Laird of Ardkinglas, was a force to be reckoned with. In 1674 he led the naval expedition against the Macleans and successfully captured the "curtain-wall" castle of Duart on the south-east coast of the Isle of Mull. The Macleans paid the price for failing to pay debts owing to the Earl of Argyll. Sir Colin was created Baronet of Nova Scotia in 1669 by King Charles II, a hereditary title.

Archibald (1629-1685), the 9th Earl of Argyll, had been condemned to death for treason in 1681, then escaped from Edinburgh Castle in disguise on the evening prior to the sentence being carried out, evaded capture during the pursuit to London and fled to Holland in 1682. His estates were confiscated, a large reward was placed on his head and he remained in exile. By 1685 considerable numbers of English Whigs and Scottish Covenanters had found refuge in Holland to escape the wrath of James II. Monmouth and Argyll, together with a number of other exiles, planned a simultaneous invasion of England and Scotland. Argyll was the first to set sail on 2nd May 1685 to invade Scotland and on arrival in Kintyre he sought to muster his clansman at Tarbert, but only around 2,000 answered the call. His people were never to feel the same loyalty to the 9th Earl of Argyll after his father had fled the field of battle on two occasions in 1644, leaving the heads of Campbell families to be slaughtered by the enemy. They quickly captured Ardkinglas Castle and then moved on south via Gareloch, but there was a lack of unity in the ranks and the invasion subsequently failed. Monmouth's invasion of England's south-west coast had been delayed by his late departure from the Continent.

Argyll was taken prisoner near Paisley and was executed ten days later on 30th June at Edinburgh. Meanwhile, the Campbells who had supported Argyll rapidly dispersed back to the West Highlands. James II quickly sought retribution and the Privy Council instructed the Marquis of Atholl, the hereditary enemy of the Campbells: "Destroy what you can to all who joined any manner of way with Argyll. All men who joined...…are to be killed or disabled from ever fighting again; burn all the houses except honest men's, and destroy Inveraray and all the castles; and what you cannot undertake, leave to those who come after you to do...Let the women and children be transported to remote islands..."(3).

So it was that Atholl's men formulated a plan, a plan conceived with a somewhat different agenda than that of the Privy Council. In accordance with the custom of the times they paid a "visit" to the Campbell lands around Inveraray. Great numbers were put to death without trial. Over 300 of both sexes were transported to the colonies and sold as slaves and the majority of the Earl of Argyll's country was laid waste with fire and sword. Fourteen Campbell lairds were hanged at Inveraray, an obelisk in the Bank garden marks the gallows-site; of those who escaped, one was safely overseas and Sir Colin Campbell of Ardkinglas hid for over a year in the romantic complex of caves above Moneveckatan that still bears his Gaelic name, Uamh-vic-Iain Riabhaich. And, there his faithful tenants fed him when Ardkinglas Castle was in the possession of Atholl's men.

But what was the "booty" that Atholl's men spirited away to Blair Atholl? They raided the shrubberies, orchards and nurseries around the original 15th century castle at Inveraray and carried away no less that 34,400 trees, some being 16 years of age! The records of the Atholl Family provide a detailed record of the "lifted” trees: " - Beech (600), Silver Fir, Spanish Fir, Pinaster, Pine, Yew, Holland Tree (Holly), Lime, Buckthorn (American), Black Popular, White Popular, Chestnut, Horse Chestnut, Walnut (American), Fir, Ash, Plane, Elm, Pear, Apple, Plum and Cherry” (3).

It is unlikely that there has ever been a raid with such an objective before or since! A more puzzling aspect is how the "visitors" managed to move such a large consignment to Blair Atholl on the other side of the Grampian Mountains when there was no road eastwards from Loch Fyne; perhaps they were taken by sea to Fort William and then overland via Glen Spean and Loch Laggan.

The devastations and havoc caused by the Wars of Succession and Independence, at the end of the 13th and 14th centuries, and their aftereffects, did much to waste the tree-growth of Scotland. As early as 1424 there was an Act under Scottish Law imposing a penalty on stealers of greenwood and destroyers of trees. An Act of 1503 supplemented the earlier legislation by requiring every landowner to plant at least one acre of wood where there is "na gret woode nor forreste." By 1535 stronger measures were enacted that destroyers of greenwood should be punished with death for the third offence; other Acts were to follow and an old Ayrshire rhyme still in vogue at the turn of the 19th century says, If you destroy Ash, Oak or Elm tree, Thy right hand cut off shall be...

The compensation claim made for the trees "lifted" from Inveraray was settled some years later for Scots £13,000. However, the main point to be made is that by the mid-1600s the Earl of Argyll's extensive collection of trees and plants was widely admired and the c 1630 reference to Inveraray and Ardkinglas suggests that the latter benefited from the collection (4).

After over a year of hiding in the cave Sir Colin Campbell was captured and imprisoned in Blackness Castle. He was sent on to Edinburgh, found guilty of high treason and imprisoned for some years. Sometime after the Revolution of 1688 he was released. No records have been found that detail the damage that Atholl's men inflicted on Ardkinglas Castle and the other Campbell strongholds, but it must have been considerable. By 1691 Sir Colin Campbell was Sheriff of Argyll and the following January it was he who received at Inveraray the oath of allegiance to King James from Alexander MacDonald (MacIan of Glencoe, chief of his clan). Campbell was away celebrating the New Year when the aged MacDonald chief arrived at Inveraray, but notwithstanding the oath was administered five days late, he sent an express to inform the Privy Council, an express whose receipt would be expunged from their records after the massacre. And, the ghosts still linger in Glen Coe. Sir Colin also served as MP for Argyll from 1693 to 1702. Despite all these distractions he still found time to lay out and develop the lands around Ardkinglas.

|

|

Ardkinglas House,

the last great country house to be built in Scotland, with its long

terrace and lawns sloping down to the upper reaches of Loch Fyne. It is difficult to comprehend that this imposing neo-baronial mansion with over eighty rooms was completed by Robert Lorimer and his artisan staff, with its Arts & Crafts interior, in less than eighteen months in an era when there was little mechanical construction equipment available. Along the bottom of the terrace is a row of the vivid-orange Ghent Azalea ‘Gloria Mundi', flanked by two M. sieboldii . Photo by John M. Hammond |

Garden Development Begins at Ardkinglas

In 17th century Scotland the kitchen garden, flower garden and orchards were usually located in close proximity to the house or castle. Some authorities suggest this was primarily for convenience or to guard against theft, but the main purpose was for sheltering the plants and trees from the incessant wind, as Sir Herbert Maxwell clearly underlined almost a century ago in Scottish Gardens. At Ardkinglas sometime in the early 1700s these gardens were moved away from the Castle, presumably in the early stages of developing the designed landscape; however, there would have been an abiding need to provide shelter from the desiccating winds. By this date the Castle was showing signs of its age and the scars of battle; but in reality its living quarters and facilities were antiquated.

Several famous architects were commissioned to make sketch designs for a classical style country house. The first of these in c. 1710 was Colen Campbell, descended from the Cawdor Family, who was responsible for the design of several classical buildings in the City of London and many country houses, but nothing came of these sketches.

Many past publications suggest that the Walled Garden at Ardkinglas, sometimes referred to in old documents as the "Kitchen Garden," was constructed in the early 1800s, but this was almost certainly the work of Sir James Campbell, 11th Laird from 1709, who carried out the development of the designed landscape at Ardkinglas and Gargunnock in the same period. In c. 1675 he inherited Gargunnock Estate, near Stirling, through marriage to Margaret Campbell of Gargunnock (5). Walled gardens of trapezoid shape were built around 1720-30 on both estates, two of the sides of each not being square on account of their following the higher contours of the land to the rear of the garden. Some aspects of construction are similar, even though there is a difference in the materials employed for the inner walls due to the use of locally available resources. This suggests that the same building "team" were used at both locations. There is reason to conclude, from other records which name "James Campbell" as being responsible for building the walled garden at another Campbell residence, that the same expertise was used elsewhere in Argyll.

As an interesting aside, the main wall of the Walled Garden at Ardkinglas faces south-west and was thus set in alignment with the main wall and keep of the Castle; indeed, at this period there were probably no trees to block the view between the two structures (see Fig. 1). From the Walled Garden entrance gate, set centrally in the main wall, a pathway ran at right angles across the garden; this was then bisected by another path set at right angles to it, thus forming a cross. A stone pedestal fitted with a carved brass sundial was originally placed at the intersection of the two paths. This probably carried the Coat of Arms of the House of Ardkinglas, as did that at Gargunnock. Sundials were a traditional point of focus in Scottish gardens at this early date. Some were hugely elaborate carved stone centrepieces, but those of hand-worked brass would have also been expensive. The original brass sundial at Gargunnock, dated 1731, still exists and is in safekeeping. A further pathway was positioned a few feet from the inner face of the wall and this ran completely round the garden, as did that at Gargunnock (5).

|

|

R. 'Bouquet de Flore',

a Ghent azalea by Verschaffelt

dating from 1864 in the 'Ladies Garden'. Photo by John M. Hammond |

The 3rd Duke of Argyll's Influence on Garden Development

The timescales of the development work at Ardkinglas fit in well with the large-scale development carried out at Inveraray. Archibald Campbell (1682-1761), later 3rd Duke of Argyll, was one of the great gardeners. It is not generally realised that, in the midst of the on-going hostilities with the "Olde Enemy," the Campbell Family owned property south of the Border. Archibald was greatly interested in horticulture and the cultivation of exotic plants and began planting in 1722 when he purchased wasteland, part of Hounslow Heath, at Whitton to the west of the City of London. His first years at Whitton were devoted to this pastime. Initially he created a large nursery area, and then in 1725 his first residence, Whitton Park, was constructed. This was replaced in 1735–1736 by a Palladian villa, built by Archibald to accommodate his long-time mistress, Mrs. Elizabeth Ann Williams. It had stabling for twelve horses and 9 acres of formal gardens, and by 1736 the additional purchases of land had created a 55-acre estate (6). A long ornamental canal was constructed in the formal gardens to act as reflection pool for the five-storey turreted gothic tower built of brick, with an open arch at the base, at the distant end of the garden.

Archibald Campbell was particularly interested in trees and also preferred the challenge of landscaping an area of uncompromising barren land. His most extreme challenge took place on his estate at Whim Hall, near Lamancha in Peeblesshire; this little known venture began in 1729 with plantings on the high bleak open moorland, but this is another story. In the 1730s Archibald acquired many North American specimens collected by John Bartram (1699-1777), the Quaker botanist of Darby, Philadelphia, and his son William, and distributed by his London-based partner Peter Collinson (1694-1768) to the gardening aristocracy. Collinson was a Quaker haberdasher with a business in Graceland Street from which he carried on a trade with the North American Colonies. Bartram first collected rhododendrons almost by accident in the autumn of 1736 whilst tracing the course of the local Schuylkill River back to its source in the Blue Mountains. He stumbled across groves of Rhododendron maximum , and it appears he dug out a batch of young plants, wrapped them in moss and these found their way back to Peter Collinson's garden in Peckham (7). It is highly likely that at least one of these plants found its way Whitton Park as Philip Miller (1691-1770), curator of Chelsea Physic Garden for almost fifty years, records there were rhododendrons at Whitton Park.

Over the years that Whitton Park developed into one of the horticultural wonders of the 18th century his brother John Campbell (1680-1743), 2nd Duke of Argyll, was formulating an ambitious plans to rebuild Inveraray Castle and develop the grounds. In 1743 Archibald, now aged 61, inherited his brother's three vast schemes: to rebuild the crumbling castle, to remove the town and rebuild it on a new site and to layout an immense formal landscape.

He brought the Palladian architect Roger Morris with him to Inveraray when he came north in 1744 and work began the following year in the midst of the '45 uprising. And, as the three elements of the massive project were inseparable, the work progressed simultaneously on all three for many years. It is worth making the point that Archibald, with his experience of laying out the grounds and plantings at both Whitton Park and Whim Hall, had both the ability and practical knowledge to lay out the grounds at Inveraray. It is said that he was able to perceive how an architectural design, or a landscape development, would look to the eye at an early stage of the physical work. One of his first actions was to replace James Halden, the Head Gardener at Inveraray, whom he thought was a "bungler." Despite these major distractions, Archibald retained his botanical interests and between 1748 and 1750 received three boxes of seed from Bartram, each box containing up to 100 varieties of seeds and seedlings, including rhododendrons. However, Mary Cosh, sometime research assistant to the 11th Duke of Argyll, records that: "...seeds from many kinds of tree were sent to him [Archibald] from abroad - many from friends in North America - to be raised at Whitton, and their offspring despatched every year to the nurseries of friends in Scotland...long before he left London for Scotland in July 1744, Duke Archibald had not only briefed his architect but started negotiations for a competent gardener...His inheritance of the Argyll estates opened up...whole new fields of experiment to this versatile Duke..."(8).

By 1748 Peter Collinson had moved his home to Mill Hill and was immensely proud of the rhododendrons in his garden. Little wonder that records indicate that of the wide variety of trees and plants grown at Inveraray a significant number were first introductions to Scotland. Following Archibald's death in 1761 his nephew, the 3rd Earl of Bute, arranged for the transfer of many specimen trees and plants from Whitton Park to Kew where he was advising Augusta, Dowager Princess of Wales, on the layout of her garden, as Peter Collinson noted: "...This spring, 1762, all the Duke of Argyll's rare trees and shrubs were removed to the Prince of Wales garden at Kew"” (9).

A number of these trees are still to be seen at the R.B.G., Kew. Nevertheless, it would be reasonable to conjecture that John Campbell (1693-1770), 4th Duke of Argyll, would not have agreed to the Earl of Bute disposing of plants and trees from Whitton Park without there being other similar specimens extant at Inveraray or at another Campbell estate.

|

|

|

|

A 'view to die for'

taken from the Dining Room of Ardkinglas House looking up

the reaches of Loch Fyne. The 'Caspian' lake, in the shape of its namesake, was an immense undertaking as it was dug out by hand. Across the years the white cottage has been the home of Head Gardener. Around the water's edge are a wealth of rhododendrons, azaleas and trees. Photo by John M. Hammond |

The 'Ladies Garden'

backs onto the Walled Garden and was traditionally

looked after by the Lady of the House. At the end of First World War the intricate formal beds were cleared out completely and were planted with a large shipment of Ghent Azaleas sent as a gift from Belgium by a refugee family of nurserymen who were found a home and looked after by the Noble Family for the duration of the War. Many of the Ghent azaleas still survive amidst the Knap Hill, early-occidentale and Rustica Flora Pleno hybrids. Photo by John M. Hammond |

The Influence of the 3rd Duke of Argyll on the Development of Ardkinglas

The importance of Archibald Campbell's botanical interests should not be underestimated in terms of its impact on Ardkinglas and the other Campbell gardens in Argyll. It would be reasonable to conjecture that during Archibald's lifetime shipments of both seeds and plants were sent from Whitton Park to the nurseries at Inveraray, Whim Hall and other major Campbell gardens such as Ardkinglas. Indeed, it is likely that this was the means by which some of the early rhododendrons were first introduced to Scottish gardens. Unfortunately, research work to date has not enabled this suggestion to be verified. Until it is practicable to gain access to the Campbell Family records held in Inveraray Castle Archives the full significance of the part played by a succession of Earls and Dukes of Argyll in the horticultural world will remain something of a legend. Whitton Park disappeared beneath housing estates built in the 1930s, but Horace Walpole, who lived at Twickenham close to Whitton, wrote in 1782: "...The introduction of foreign trees and plants, which we owe principally to Archibald, Duke of Argyll, contributed to the richness of colouring so peculiar to our modern landscape" (10).

There is little evidence as to the early appearance of the landscape at Ardkinglas other than depicted in William Roy's Military Survey of Scotland (1747-1755), commissioned by the Government in the wake of the '45 uprising. This survey clearly indicates the existence of a shelterbelt planted to the south of the Castle. To the north the entire Rhubha Mor peninsula (bounded by the Kinglas estuary and Loch Fyne) is sub-divided into several enclosures, and to the east of the River Kinglas (later to become the site of Ardkinglas Woodland Garden) there is a somewhat isolated small group of trees. There is little doubt that these plantings were in stark contrast to the harsh moorland mantle of the surrounding landscape. It would appear that Roy's survey was completed long before many of the plantings at Ardkinglas or Inveraray had been made as Knox was at Inveraray in 1786 and says that: "...the house was surrounded with more than a million trees, which occupy several miles square" (Vol. 1. p552-553).

In his memoirs James Callander (later to be Sir James Campbell, 15th Laird of Ardkinglas) wrote: At the time of my birth, my father and mother were on a visit to my great grandfather Sir James Campbell; at his baronial seat of Ardkinglas on the banks of Loch Fine...It was a fine old mansion, built in the form of a quadrangle, with a considerable courtyard at the centre. At each corner was a tower of sufficient dimensions to make it the residence of some cadet of the family. I have often regretted that the late Sir James Campbell should have thought of demolishing this noble pile, for the purpose of raising in its stead a great square of masonry, which has nothing to recommend it but its conformity to the modern ideas of domestic comfort and accommodation...The date was the 21st of October in the year 1745...It is said that Prince Charles Edward was for some time in the house of Ardkinglas in the year 1746; and a bonnet is still preserved in the family, in the belief that it had been placed on my infant head by the hands of that unfortunate aspirant to the crown of Great Britain (11).

On the death of Sir James Campbell, 11th Laird, on 5th July, 1752, the direct male line of the House failed and he devised his Barony to his daughter Helen, who married Sir James Livingstone Bart, of Glentirran, who took the name Campbell and became the 12th Laird. Sir James Livingstone's grandfather was the 2nd Earl of Callander.

|

|

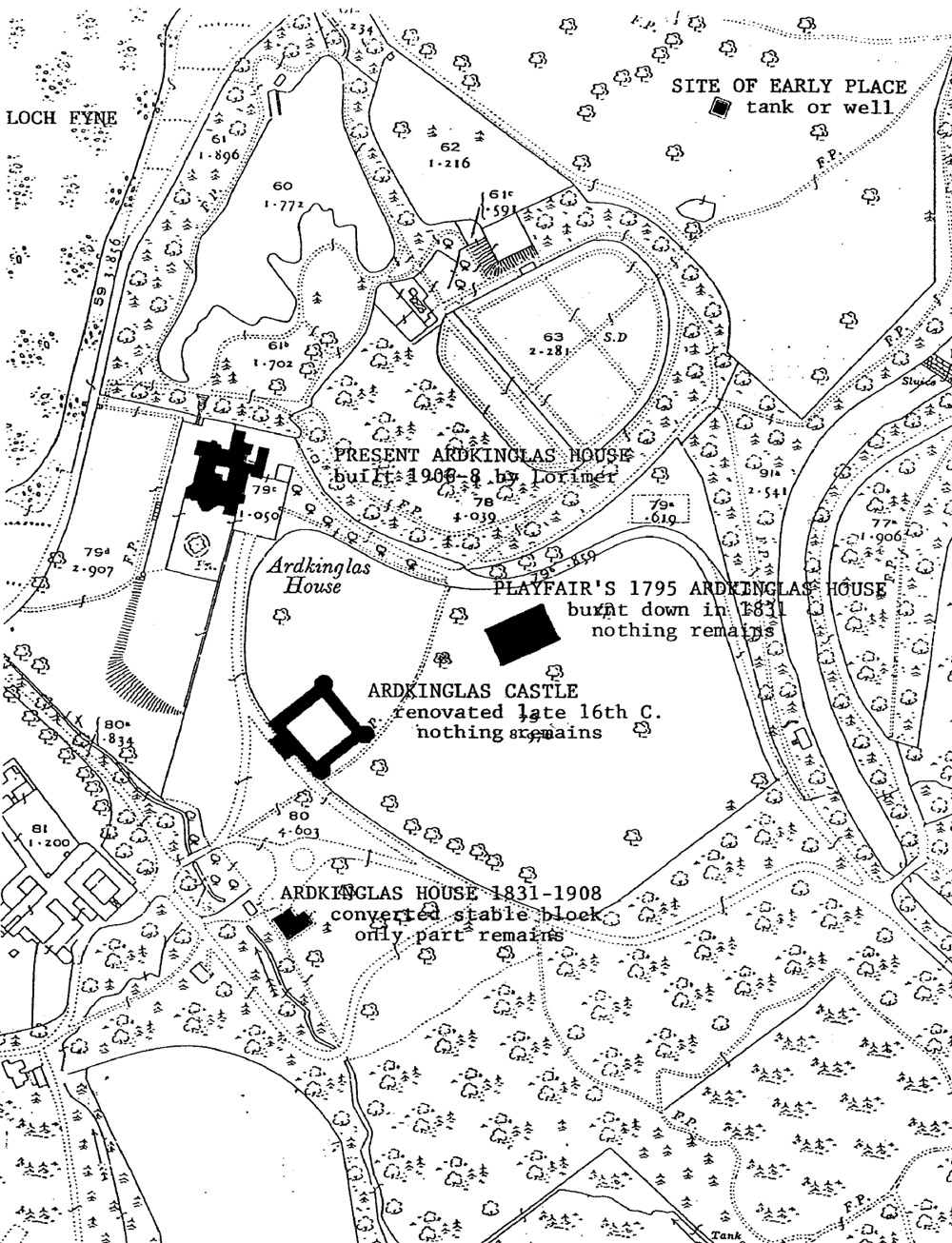

Figure 1. This

diagram shows the location of all five structures built at Ardkinglas over the

centuries since 1396. Towards the top of the page,

in the centre, is the large Walled Garden with its sundial (s.d.) positioned at the intersection of the paths. Note that the front wall of the Walled Garden is firstly, exactly parallel to the rear wall of Ardkinglas Castle and, from a security point of view, in direct line-of-sight of the two towers; secondly, a means of shelter for the "Ladies Garden" that occupies a large area immediately outside the Walled Garden. To the left of the Walled Garden is the "Caspian Lake" that was excavated by hand. The meandering River Kinglas can be seen on the extreme right of the diagram, its waters being the boundary of Ardkinglas Woodland Garden that encompasses an area of higher ground to the east. |

References

1. Campbell, Niall Diarmid. 1905. Letter to Tenantry of Ardkinglas.

2. Ardkinglas Estate. 1905–1996. Estate records and documents relating to

Ardkinglas House, gardens and woodlands.

3. Atholl, Duke of. 1908. Chronicles of the Atholl Family.

Published privately. Vol. 1., p. 265.

4. MacFarlane, Walter. 1906-08. Ane Descriptione of certaine pairts of

the Highlands of Scotland; MacFarlane's Geographical Collections.

Scottish History Society (Edinburgh). Vol.2: 144-146.

5. Hammond, John M. 2001. The Development of the Gardens and Design

Landscape of Gargunnock House. Scottish Rhododendron Society,

Yearbook No. 4, 2001: 9-18.

6. Foster, P. & Simpson, D.H. 1999. Whitton Park and Whitton

Place. Borough of Twickenham Local History Society. Paper No.41, 1999.

7. Brett-James, Norman G. 1925. Life of Peter Collinson. Dunstan.

8. Lindsay, Ian J. & Cosh, Mary. 1973. Inveraray and the Dukes

of Argyll. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh.

9. Transactions of the Linnean Society, 1811; 275.

10. Walpole, Horace. 1782. The History of Modern Taste in Gardening.

Ursus Press, New York. (Reprinted 1995).

11. Campbell, Sir James. 1832. Memoirs of Sir James Campbell, of

Ardkinglas. Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley, London.

John Hammond is a member of the Scottish Chapter.