JARS v64n2 - Utilization of Rhododendrons by Monpas in Western Arunachal Pradesh, India

Utilization of Rhododendrons by Monpas in Western Arunachal Pradesh, India

Ashish Paul and Mohamed Latif Khan

Department of Forestry, North Eastern Regional Institute of Science and Technology

Deemed University, Arunachal Pradesh, India

Ashesh Kumar Das

Department of Ecology and Environmental Science

Assam University, Assam, IndiaAbstract

India is considered the homeland of many traditional medicines. The country has a large number of ethnic communities with a rich knowledge of these products. Arunachal Pradesh, a hilly state in northeastern India, has both extensive plant resources and ethnic diversity, resulting in the existence of many traditional medicines. Monpas are the predominant community of western Arunachal Pradesh that use Rhododendron for various purposes, including as a preferred fuel because of its burning characteristics. Medicinal uses of Rhododendron have been poorly documented to date in India, and here we describe the utilization and importance of these high altitude plants in western Arunachal Pradesh. Data was collected through interactive surveys of indigenous peoples, and usage of 34 Rhododendron taxa is described. Three (9%) taxa had medicinal importance, 19 (56%) had fuelwood value, and 12 (35%) had both values.Introduction

Subsistence plants, i.e., those local species used for medicine, food, fuelwood, fulfill many important needs in both rural and urban communities in India. Northeastern Indian States contain more than 130 of the 427 tribal communities found in India (Sajem and Gosai 2006), and this region is known to have a high diversity of medicinally important species. Various indigenous communities are fully or partially dependent on herbal medicines for the treatment of various ailments, but utilization and application can differ from one locality/community to another.

Arunachal Pradesh is located in the Eastern Himalayas, a global biodiversity hotspot (Myers et al. 2000), and is one among 200 globally identified important ecoregions (Olson and Dinerstein 1998). It is situated between 26° 28' to 29° 30' N latitude and 91° 30' to 97° 30' E longitude, and has an area of 83,743 sq. km, making it the largest state of northeast India. It is bounded by Myanmar in the east, Bhutan in the west, China in the north and Assam in the south. Forests cover 67,777 sq. km (81%) of its area (FSI 2005). It has 26 major tribes and over 110 sub-tribes (Bhagwati 2002) inhabiting different parts of the state, many with intricate economies totally dependent on forest resources.

Monpas are one of the major tribes in the West Kameng and Tawang districts of Arunachal Pradesh. They are of Tibetan origin, are Mongoloid, follow Buddhism and are peace-loving. They are mostly farmers with animal husbandry as a secondary occupation (Anonymous 2005). The name "Monpa" is derived from two Tibetan words, 'mon' meaning south and 'pa' meaning dweller, since they are at the southern end of the geographical range of Tibetans (Chand 2004). Other tribes inhabiting the West Kameng district are Miji (Sajolang), Sherdukpen, Aka (Hrusso) and Khawa (Bugun) (Anonymous 2005, Dollo et al. 2006). Monpas have their own customs and regulations and a rich cultural heritage. Their main festival is "Losar" (New Years Day), but other festivals are also celebrated for different occasions. Each festival is associated with utilization of various plants and plant products of ethnobotanical significance. Rhododendrons are one of the preferred plant species used by Monpas in different ways and occasions. Different rhododendron species were documented as part of traditional knowledge with names in their own dialects (Table 1). The plant species are named according to use and belief, and local peoples are well acquainted with plant species occurring in this high altitude forest area.

Several plant species of medicinal, aromatic and economic importance have been reported from the state. However, there is no previous documentation of utilization of Rhododendron from Arunachal Pradesh.

Materials and methods

Extensive field surveys were carried out in different localities of West Kameng and Tawang district of Arunachal Pradesh during 2005-2006. Different uses and utilization patterns of rhododendrons were gathered through conversations with local people.

|

|

Fig. 1. Burning of

mixture of

R. arboreum

and pine leaves to purify surrounding air.

Photo by the authors |

Results

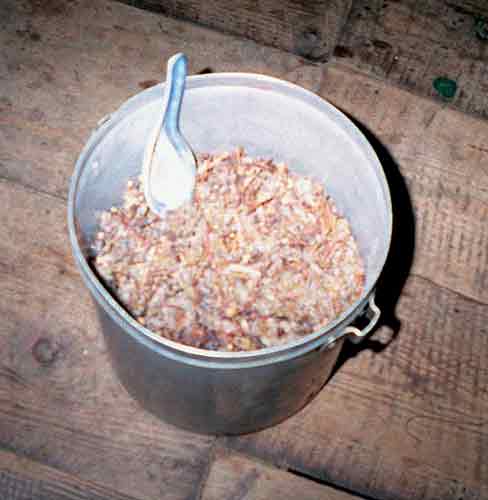

We recorded the utilization of Rhododendron leaves, flowers and wood as both raw and processed materials for different purposes. Rhododendron flowers from R. arboreum ssp. arboreum , R. arboreum ssp. cinnamomeum , and both R. arboreum ssp. delavayi var. delavayi and var. peramoenum have a sweet taste and are consumed raw. Beautiful flowers are also considered sacred and are used as offerings in temples and monasteries (Figure 2). Leaves of R. anthopogon are used in the preparation of incense that is widely used in both households and Buddhist monasteries, especially during rituals and celebrations (Figures 4, 5). Monpas use R. edgeworthii leaves in distillations to cure skin diseases. Fresh leaves of R. arboreum ssp. arboreum , R. arboreum ssp. cinnamomeum , and both R. arboreum ssp. delavayi var. delavayi and var. peramoenum , in combination with many gymnosperms such as juniper, thuja (arborvitae), pine, etc., are burnt in sacred places, which produces an enormous amount of smoke that is believed to be sacred and which purifies the surrounding air (Figure 1). Wood from these species is also durable and is used in making handles for various tools and implements as in making boxes, spatulas and spoons. Leaves of R. falconeri ssp. eximium , R. grande , R. hodgsonii , and R. kesangiae var. album are large in size and are used as packing material for various yak milk products (e.g., ghee, churpi) (Figure 6). Leaves are also used as packing material for transportation of various agricultural products including apples. The underside of R. fulgens leaves with its dense wooly indumentum is used as a fire starter in household fires. Rhododendrons are also a preferred fuelwood of local inhabitants because of its burning capacity even when in a green condition (Figure 3). This may be due to the rich oil (polyflavenoids and other resinous substances) content of green wood. Different uses of documented Rhododendron species are presented in Table 1.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 2. Flowers for

offering in monasteries.

Photo by the authors |

Fig. 3. Stock pile of

rhododendron for fuelwood.

Photo by the authors |

|

|

|

|

Fig. 4. Crushing of leaves

of

R. anthopogon

to make incense.

Photo by the authors |

Fig. 5. Crushed leaves of

R. anthopogon

ready to use.

Photo by the authors |

|

|

Fig. 6.

R. hodgsonii

leaves used for packing ghee.

Photo by the authors |

Discussion

Altogether, different usages of 34 Rhododendron taxa were documented during the present study. Three (9%) taxa had medicinal importance, 19 (56%) had fuelwood value, and 12 (35%) had both values. Major harvesting of rhododendrons in the study area occurs for fuelwood, which is used for both cooking and room heating. Local communities inhabiting the colder regions of Arunachal Pradesh mainly depend on rhododendrons for fuel, both because of its good burning qualities and its relative abundance. The most important medicinal use was recorded for two taxa, R. edgeworthii , which were found to be effective against some skin diseases, while R. dalhousiae var. rhabdotum also had active insect repellent qualities. This traditional knowledge needs to now be scientifically evaluated to identify the active compounds, as these may have other significant applications. Incense stick making is common in Monpa dominated areas, and large quantities of R. anthopogon leaves are used for this purpose. The resulting incense is used in both rituals and in daily activities that are considered to be sacred and which are obeyed with great honour. Similar uses were also reported by Pradhan and Lachungpa (1990) and Tiwari and Chauhan (2006) for R. anthopogon from Sikkim Himalaya. Wood of large Rhododendron trees is preferred for making household appliances, tools, traditional crafts, etc. Such use of R. arboreum wood by local inhabitants has been previously reported from Sikkim (Pradhan and Lachungpa 1990; Singh et al. 2003). Use of large leaves of a few taxa as packing material is also very common and was again previously reported by both Pradhan and Lachungpa (1990) and Tiwari and Chauhan (2006) from Sikkim Himalaya, as was the use of the dense indumentum of R. fulgens for fire starting from Sikkim (Pradhan and Lachungpa 1990).

In conclusion, local people depend on rhododendrons for many uses. These plants also have both aesthetic and sacred value. Educating local communities on how best to both conserve and sustainably utilize rhododendrons in Arunachal Pradesh is thus important.Acknowledgements We thank the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), New Delhi, for financial assistance. We also thank villagers for their help and cooperation during the survey, and to Mr. Bijit Basumatary for his survey assistance.

References

Anonymous. 2005. Statistical abstract of Arunachal Pradesh . Directorate of Economics and Statistics. Government of Arunachal Pradesh.

Bhagwati, A.C. 2002. Social structure in Arunachal Pradesh: An anthropological overview. In: Sundriyal, R.C., Singh, T. and Sinha, G.N. (eds.). Arunachal Pradesh: Environmental Planning and Sustainable Development - Opportunities and Challenges . Himavikas Occasional Publication No. 16, G. B. Pant Institute of Himalayan Environment and Development, Kosi-Katarmal, India: 47-50.

Chand, R. 2004. Brokpas: The hidden highlanders of Bhutan . Pahar Publishers: 23-70.

Dollo, M., S. Chaudhury, and R.C. Sundriyal. 2006. Traditional farming and land tenure systems in West Kameng district, Arunachal Pradesh. In: Ramakrishnan, P.S., Saxena, K.G. and Rao, K.S. (eds.). Shifting agriculture and sustainable development of north-eastern India: Tradition in transition . Oxford and IBH Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi: 293-315.

FSI. 2005. State of forest report 2005 . Forest Survey of India. Ministry of Environment and Forests, Dehradun, India.

Myers, N., R.A. Muttermeier, C.G. Muttermeier, G.A.B.da Fonseca, and J. Kent. 2000. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403(6772): 853-858.

Olson, D.M. and E. Dinerstein. 1998. The Global 200: a representation approach to conserving the earth's most biologically valuable ecoregions. Conservation Biology 12(3): 502-515.

Pradhan, U.C. and S.T. Lachungpa. 1990. Sikkim-Himalayan Rhododendrons. Primulaceae Books, Darjeeling, West Bengal, India. 130 pp.

Sajem, A.L. and K. Gosai. 2006. Traditional use of medicinal plants by the Jaintia tribes in North Cachar Hills district of Assam, northeast India. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2(33): 1-7.

Singh, K.K., S. Kumar, L.K. Rai, and A.P. Krishna. 2003. Rhododendrons conservation in the Sikkim Himalaya. Current Science 85(5): 602-606.

Tiwari, O.N. and U.K. Chauhan. 2006. Rhododendron conservation in Sikkim Himalaya. Current Science 90(4): 532-541.