QBARS - v9n4 Better Than Expected

Better Than Expected

By David G. Leach

This last spring I spent a little over two months in the principal rhododendron collections of England, Scotland and Wales, assembling technical data for the book on rhododendrons on which I have been working for several years. Both "The Species of Rhododendron" and "The Rhododendron Handbook," the standard reference works for botanical statistics, contain so many errors that I felt compelled to obtain my own measurements and observations in the interest of accuracy.

In the course of examination so exhaustive that it included the study by microscope of the botanical characteristics of many species, I acquired a new awareness of the merit of some of them. Such minute observation in numerous gardens in a variety of climates produced gradually, in the course of my study, an impression of outstanding garden value in certain rhododendrons which are really not very well known. I do not know why they have been neglected. I do know that they deserve a prominence which they do not now enjoy.

|

|

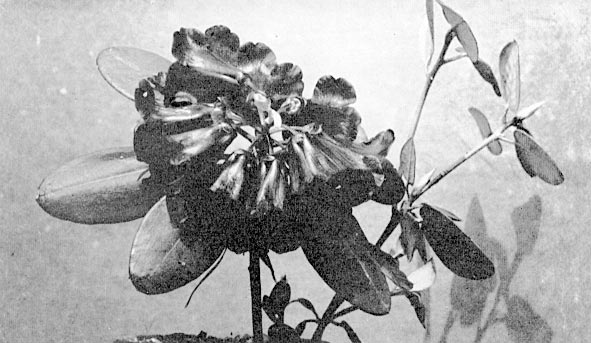

Fig. 38.

R. thomsonii

R. Henny photo |

The earliest blooming and the most conspicuous for its oversight considering its extraordinary beauty is R. hylaeum . It is a 15-foot shrub with good foliage and a fine growth habit. The large, rounded flower trusses are a unique salmon pink shade which is oddly luminous and tremendously appealing. Everywhere I saw this species it was a cascade of color, one of the most free blooming and attractive rhododendrons of its season. Inexplicably, this species of the Thomsonii series earns no quality stars in "The Rhododendron Handbook," an assessment of its garden value which is about as accurate as the May blooming season given therein. It actually blossoms in early April. Kingdon Ward No. 6401 is a particularly fine form. If I had to choose between it and the celebrated R. thomsonii I would unhesitatingly select R. hylaeum . There are other good red flowering rhododendron species in early spring but none with pink flowers the equal of this.

Another good early flowering sort which has not received its due is R. planetum , of the Fortunei series. It is one of those rugged, adaptable sorts which seem to do well in any garden situation, and I know of no species of its season which appears to such advantage in so great a variety of planting sites. The loose clusters of white or clear pink blossoms are borne in the greatest profusion on shrubs 8 or 10 feet tall. Every gardener who owns it praises its amiability and the reliable floral display. It is surely among the very best of the rhododendrons which flower in the first part of April.

R. fulvum is maligned in "The Rhododendron Handbook" when it states that ". . . the flowers are small . . . . This statement needs further qualification, to put it charitably. It is true that the white blossoms of Kingdon-Ward No. 8300, which are often seen in gardens, are not particularly showy, but some of the selected rose-pink forms bear trusses of impressive proportions, studding the ends of every branch with stunning globes of sparkling color in a rousing spring spectacle. R. fulvum already has a small reputation as a good foliage plant. The rich indumentum beneath handsome glossy leaves makes it striking at all seasons, a 15-foot shrub of extraordinary distinction. It deserves now to have its name enhanced by the quality of its flowers in selected forms, making it one of the best all-around garden species in the genus. It blooms in April.

R. racemosum x R. spinuliferum 'Spinulosum' is an early-blooming hybrid, too little known and seldom listed by nurserymen. Progeny of one of the most floriferous of all rhododendrons on the one side, and of the most unique in flower shape on the other, seedlings of this cross display an astounding range of color and conformation in their little blossoms. Always interesting, always free blooming, this hybrid with its myriads of deep, cup-shaped flowers ranging from pink through red to orange is a garden asset which seems to me to have been grossly undervalued. It is a shrub 6 or 8 feet tall.

|

|

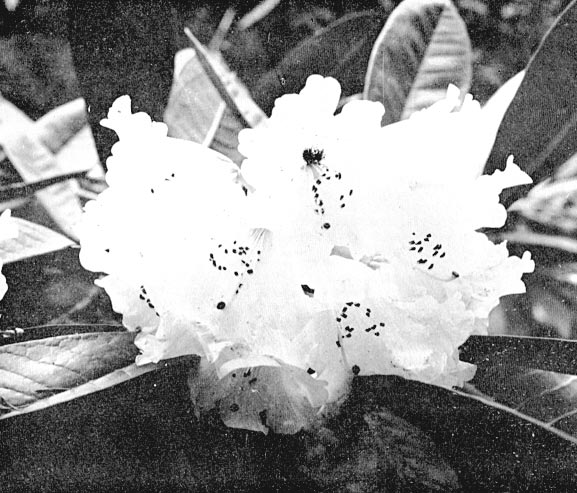

Fig. 39.

R. eclecteum

R. Henny photo |

Another rhododendron with flowers of an extraordinary color range is R. eclecteum , a six-foot shrub in the Thomsonii series. The variety is simply unbelievable. The flowers, 2½ inches in diameter in loose trusses, vary from white and deep cream through various shades of buff to clear yellow: from palest pink through lovely pastel salmon and coral tints to a strong, vibrant rose; from light mauve through a series of lavender gradations to violet-lilac: and from orange through unusual coppery intermediate shades to brilliant scarlet and deep crimson. In addition, rose-red often appears as an edging on flowers of quite another color, suffusing them to a varying extent and thus creating a multitude of entirely different effects. Out of this host of unique colors the buff and yellow flowers edged rose-red are among the most striking, but all are remarkably attractive and especially when a considerable range of them are planted together. This species blooms very early in the spring, and the choosing of the right site makes the difference between a splendid and a poor garden performance. It should be placed in a protected spot shielded from the morning sun on frosty mornings.

R. glischroides is a first rate species which makes a brave show of delicate pink flowers effectively set off against deep green, hairy foliage in late March and early April. It is usually seen 5 or 6 feet tall, with dense shapely habit, and it is one of the best sights of the season, a distinctive shrub with a strong and appealing character.

R. uvarifolium is another little known rhododendron which sticks in my mind for its outstanding garden quality in the selected forms with large, rounded trusses of white flowers, just touched with pink to warm their beauty. This is a robust small tree in the Fulvum series, 15 feet tall or more, with fine foliage which bears a startling white indumentum beneath the rich green leaves. In its best expressions, the floral display is spectacularly effective in late April and early May.

About the same time, when competition is stiff from many fine rhododendrons, both species and hybrids, R. tsariense of the Campanulatum series shines forth as an outstanding shrub of more modest dimensions. It is only about three feet tall, a convenient height for many landscape uses. Its single tiered trusses of cream flowers, buff-yellow on the outside, are lightly spotted red and are particularly charming. Not the least of its virtues is a brilliant orange indumentum, possibly the brightest in the genus, beneath glossy dark green leaves so thickly borne that the plants are notably handsome for their foliage alone. Ludlow & Sherrill No. 2766 is a particularly fine form.

R. vellereum suffers unjustly from the reputation of the Taliense series for being shy blooming. Actually, it is a conspicuous exception, a fine garden shrub about 10 feet tall which is loaded with large rounded trusses of white flowers in April. As they open, the blossoms are clear pink briefly, and a plant with both expanding buds and fully opened flowers presents a picture of special appeal. This rhododendron deserves much wider distribution.

|

|

Fig. 40.

R. aperantum

Bacher photo |

Expert gardeners in England give R. aperantum a soil poor in nutrients and crowd the dwarf plants together to make them bloom well. Then they are remarkably effective in the garden, forming compact, billowing masses of dense foliage which supports legions of little clusters of brilliant scarlet, waxen bells in April. In my opinion, R. aperantum is more decorative and more useful as a garden plant than the free blooming forms of the well known R. forrestii var. repens . It grows about 15 inches tall and about 30 inches wide in a faultless mounded outline. Forrest No. 26936 is an especially good form.

|

|

Fig. 41.

R. forrestii

var.

repens

on a rock wall

R. Henny photo |

|

|

Fig. 42.

R. desquamatum

R. Henny photo |

R. rubiginosum is a fairly well known species, but R. desquamatum , also in the Heliolepis series, is seldom mentioned despite its being more useful in its earlier season of bloom and more handsome as a garden plant. This is another of those rhododendrons of almost unlimited usefulness, not fastidious as to site, always free blooming and reliable. In April the 12 to 15-foot shrubs are mantled with unbroken sheets of soft mauve flowers in a prodigal show of color. The smaller leaves and more slender growth give this species a lighter texture and more graceful landscape effect, which fit it for innumerable garden situations. It almost invariably appears to exceptional advantage wherever it is planted. The Exbury Estate has often exhibited at the Rhododendron Show in London a stunning violet-blue form with 2½ inch flowers, five to a truss, which has become fairly well known in England. This is almost certainly a hybrid, probably of natural origin, a chance seedling which sprang up in the Exbury collection. Microscopic examination betrays its hybridity with a species of the Triflorum series.

|

|

Fig. 43.

R. bauhiniiflorum

R. Henny photo |

R. triflorum itself is famous as the central species in a celebrated series, but its garden value is equivocal. The pale yellow flowers against the olive green foliage are pallid and without sufficient contrast to be effective. R. bauhiniiflorum is a much more determined yellow, hardier and superior in every way for those who want the airy grace and willowy growth of the Triflorum type of rhododendron in combination with yellow blossoms. An 8-foot shrub, it is rare indeed, inexplicably so considering its superiority to the species it superficially resembles.

|

|

Fig. 44. R. euchaites F.C.C. R. Henny photo |

Reviewing other impressions of the species in a general way, I was struck anew by the tremendous difference between numerous popular conceptions of these rhododendrons and the actual facts as they are revealed by study. For example, the distinction between R. neriiflorum and its presumably superior, taller growing subspecies, euchaites, is a fiction. Close observation of many specimens reveals every conceivable gradation from the low, spreading form to the tall, upright sort. There is a similar lack of substance for the popular notion that there are two distinct forms of R. campylocarpum: one, a six-foot shrub introduced by Hooker; the other, a taller, more upright form called var. elatum. The fact is that, here again there are an infinite number of intergrades bridging them and there is no real distinction between the forms. They are merely the two extremes of a continuous series.

These are only two examples of the fluid merging of presumably distinct forms within a species. There are innumerable similar cases between species.

At the great Rhododendron Show in London on May 3rd, Windsor Great Park staged an educational exhibit of the many forms of R. fictolacteum. An entire table was occupied with specimen trusses from the numerous plants in their collection. Actually, however, many of the flowers shown were R. rex, the number of one species or the other represented in, the display being purely a matter of personal opinion. The fact is that R. fictolacteum (Fig. 45) and R. rex merge in a progression of intermediate forms, and there is a substantial range between the two where the preference of the observer in emphasizing any one of several botanical characteristics determines to which species a particular plant is assigned.

|

|

Fig. 45. R. fictolacteum R. Henny photo |

Enthusiasts like to think in terms of neat pigeonholes into which the species will comfortably fit, but rhododendrons refuse to submit to such easy distinctions. Specialists are much better served by a fluid concept, in which one species flows imperceptibly into another throughout whole ranges of the genus. Perhaps a better similarity would be to liken a species to a planet encircled by innumerable satellites which resemble it in diminishing degree as their distance increases from it. The central planet is clearly distinguished as typical of the whole, but at some point the outer satellites intersect the orbit of an adjoining planet-species and they can not then be identified as belonging to one or the other.

Indeed, a moment's reflection proves the aptness of such a conception. If we but possessed specimens of every rhododendron which existed since first the genus evolved from the Magnolias and Dillenias 50,000,000 years or more ago, we would inevitably have a continuously progressive series from the large-leaved, tree-like falconeris to the creeping R. forrestii var. repens; from the Lacteum type to the Lapponicum; from the evergreen Stamineum to the deciduous Luteum. Saving only the rare abrupt mutations, the intergrades from one extreme to the other must inevitably be complete as the species, slowly and with infinitely small changes, evolved in the shifting tide of time throughout the millions of years.

As a geneticist, I am particularly interested in the evolution of rhododendrons, and I am convinced that there are literally scores of natural hybrids presently enjoying an unearned distinction as species. It is no secret that plants grown from seeds sent back by explorers do not by any means always correspond in character with the herbarium specimens taken from their parents. Such is conspicuous evidence of natural hybridity, yet the plant explorers stoutly maintain that they have never seen a wild hybrid in Asia. The emphasis, however, seems to be always on single, isolated specimens when such statements have been made. Apparently there was no thought that the progeny of natural crosses between two species might occur in hybrid swarms, as, in point of fact, they almost invariably do in the wild. Whole areas are frequently blanketed by first, second and more advanced generation hybrids if the progeny of two different species acquire dominance, as they often do because of their greater vigor. Yet it seems that the plant explorers accepted these large populations always as new species because they were not identical with other rhododendron types in the neighborhood.

Natural hybrids occur so frequently in sizable plantations of rhododendrons in cultivation that every specialist knows how hazardous it is to collect open-pollinated seeds with any certainty of obtaining from them plants identical with the seed parent. All too often the bees have brought in pollen to make one of nature's crosses with another species. In fact, they sometimes do as good a job as the hybridist, and natural garden hybrids are occasionally exhibited at rhododendron shows for their superior horticultural value.

When rhododendrons in proximity cross so readily in cultivation, it is incomprehensible to me how the collectors can continue to deny that they do so in the wild. I have in my own garden a natural hybrid between R. maximum and R. catawbiense, from the mountains of North Carolina, and the most exhaustive studies by Dr. Henry Skinner, Fred Galle and others have proved beyond doubt the abundant presence in nature of hybrids among our native azalea species. Just how the collectors in Asia envisioned the process of speciation as occurring there, I do not know.

Great as our gratitude is to the plant explorers, much as we admire their gallantry, force of character and strength of determination, the evidence is fatally against their views on this point.

It is natural hybridity that joins the older species with the newer in the endlessly shifting flux of nature. A segregated population of plants, whatever its origin, tends to become more uniform with each passing generation until finally all of its members acquire a common identity and their progeny resemble the parents. Thus are new species born by the caprice of insect and geography and the ponderous passage of the ages.

The connecting links may be lost, as they fail to survive in the endless struggle to perpetuate themselves, or because of some cataclysm of nature. But many do endure, to perplex the gardener and confound the taxonomist who studies rhododendrons. The examples are legion.

R. uniflorum and patulum are merely the extremes of a series completely devoid of any division among uniflorum, pemakoense, imperator and patulum. The imperceptible gradation from one into the other defies definition. No one can draw a line between R. saluenense and R. chameunum with any certainty of separating the two accurately. R. houlstonii merges into R. discolor. There is a shadowy realm between R. decorum and R. diaprepes where the intermediates can be assigned as well to one species as to the other.

|

|

Fig. 46. R. diaprepes R. Henny photo |

Leaf size, shape and glaucousness are presumed to differentiate among wardii, the plant formerly known as croceum, and R. litiense, but botanically they are all one species. Gardeners want a name for the form with small, oblong, glaucous leaves, so litiense has been retained for their convenience-mistakenly, I think, in view of the fact that gradations between it and wardii show no break whatever. Thus there are innumerable intermediate plants which can be identified as accurately with one name as with another.

So it is that a concentrated study points anew to the continuity of life that nature intends, and of which this is only an expression. However much we would like to classify and sort and name the species, to label them for identification and convenience, it is at best a sorry compromise with reality in a great many cases. In a broad sense we are dealing with the plastic and dynamic, and our conception of these living rhododendron species should fit the facts as they are.