JVER v27n1 - Preparing the Workforce of Tomorrow: A Conceptual Framework for Career and Technical Education

Preparing the Workforce of Tomorrow: A Conceptual Framework for Career and Technical Education

Jay W. Rojewski

University of Georgia

Abstract

A viable conceptual framework for career and technical education (CTE) or any other enterprise should represent consensus among its members concerning the scope, mission, and methods reflective of the profession. Such a framework should be dynamic, subject to frequent debate and ongoing refinement. This paper, then, provides information to stimulate the debate about the present and future of CTE using the development of a conceptual framework as the vehicle for organizing and presenting critical issues. First, the parameters of a conceptual framework are clarified, e.g., what should a conceptual framework entail? Who should develop it? How should it be used? Next, the historical record is briefly reviewed to establish a context for discussion, as well as outline the traditional positions adopted by professionals toward the scope and mission CTE. Current and projected issues affecting both secondary and postsecondary CTE are examined. A tentative conceptual framework is advanced, and implications of the proposed framework for CTE teacher preparation programs are discussed.

Increasing complexity in all facets of work, family, and community life coupled with persistent calls for educational reform over the past several decades present numerous challenges to professionals in career and technical education. The need to revise or eliminate outdated curriculum and develop new programs to meet emerging work or family trends is a seemingly endless occurrence. But, what drives the changes and modifications made to career and technical programs? Even more basic, what is the essential purpose of career and technical programs in an increasingly global economy requiring highly skilled and highly educated workers? Is career and technical education, as Prosser, Snedden and others argued nearly a century ago, solely a means for preparing young people for specific types of work, or as Dewey posited a means of academic education for living in a democratic society? Do purposes differ at secondary and postsecondary levels? Where is career and technical education headed in the foreseeable future?

Answers to these questions, and many more, depend on any number of possible factors not the least of which are the underlying philosophies, implicit assumptions, and "common vision" held by those responsible for career and technical education. Presumably, this information can be collected and coherently presented in a conceptual framework for career and technical education.

So then, "What is a conceptual framework and what should one look like for career and technical education?" In this article, I attempt to articulate "a" (rather than "the") conceptual framework for career and technical education based on the extant literature, current state of education reform, and projections of future direction for the economy, work-family-community demands, and career and technical education. Because of differing views about the nature of the field, we must recognize that for a conceptual framework to be effective and useful in (a) explaining the general purposes of career and technical education, (b) reflecting the underlying beliefs and perspectives of its constituents, and (c) shaping current activity and future direction, it cannot be developed in a vacuum. Many people and organizations must be involved to provide a comprehensive view of career and technical education and its applications in classrooms, boardrooms, living rooms, and factory floors. Therefore, this framework should be viewed as an initial point of departure for discussion and debate rather than as an arrival at the final destination.

In Search of a Conceptual Framework

Miller ( 1996 ) explained that a conceptual framework contains (a) principles or "generalizations that state preferred practices and serve as guidelines for program and curriculum construction, selection of instructional practices, and policy development," and (b) philosophy which "makes assumptions and speculations about the nature of human activity and the nature of the world...Ultimately, philosophy becomes a conceptual framework for synthesis and evaluation because it helps vocational educators decide what should be and what should be different" (p. xiii).

A conceptual framework should accomplish several things: (a) Establish the parameters of a profession by delineating its mission and current practices, (b) account for historical events to allow understanding of how we got to where we are, (c) establish the philosophical underpinnings of the field and underscore the relationships between philosophy and practice, and (d) provide a forum for understanding needed or actual directions of the field. A conceptual framework does not necessarily solve all problems or answer all questions present in a profession, but it should provide a schema for establishing the critical issues and allowing for solutions, either conforming the problem to the framework or vice versa (or perhaps both). Frameworks should be fairly stable but have the capacity to change over time and adapt to external factors.

The need for a conceptual framework has never been greater, given the state of the workplace and our society, and the demands being placed on workers and citizens for technical and higher-order thinking skills. Lewis ( 1998 ) posits that two related forces shape policy, discourse, and curriculum in vocational education: "(1) a global economy in which economic competitiveness is presumed to be linked with work force readiness, and (2) the changing nature of skill, work, and jobs, wrought largely by the impact of technology and by high-performance work organizations" (p. 13). Any conceptual framework of vocational education (career and technical education) 1 must contend with these influences.

Historical Traditions and Views Toward Vocational Education

Nearly every contemporary work that examines the nature, scope, and possibilities associated with career and technical education pays a fair amount of attention to the historical roots and subsequent development of vocational education. This particular work is no different. Why? A sense of history can foster an appreciation for the origins of the field, contribute to an understand of how and why program purposes and missions have changed over ensuing decades in reaction to political and economic concerns, define the current status of the field, and encourage the consideration of possible directions for the future.

Without historical insight, vocational educational policymakers fail to gain insights into the relationship between schooling and work that the past may provide. As a result, vocational educational leaders may devote great energy to reinventing a pedagogy incapable of addressing the demands of democracy and the needs of an evolving economy...Historical consciousness can help vocational educators recognize the inherent problems in particular assumptions or particular ways of operating and facilitate the development of pragmatic alternatives. (Kincheloe, 1999 , p. 93)

Two of the most important influences that have shaped vocational education, both at its inception and now, are federal legislation and philosophies about the nature of vocational education.

Role of Federal legislation in the nature and scope of career and technical education. Career and technical education programs in the U.S. exist because of federal legislation. In fact, since the beginning of federal support for public vocational education as mandated by the Smith-Hughes Act of 1917 (PL 64-347), the federal government has been a predominant influence in determining the scope and direction of secondary, and to a lesser extent postsecondary, vocational and technical training.

A primary force that led to passage of the Smith-Hughes Act was economic, seen in the growing need to prepare young people for jobs created as a result of the industrial revolution. As originally envisioned, vocational education was viewed as a sequence of courses and experiences that were designed to prepare individuals for paid and unpaid entry-level employment requiring less than a baccalaureate degree (Sarkees-Wircenski & Scott, 1995 ). The Smith-Hughes Act established vocational education as a separate and distinct "system" of education that included separate state boards of vocational education, funding, areas and methods of study, teacher preparation programs and certification, and professional and student organizations. Unfortunately, the legislation "contributed to the isolation of vocational education from other parts of the comprehensive high school curriculum and established a division between practical and theoretical instruction in U.S. public schools" (Hayward & Benson, 1993 , p. 3).

Vocational education, as implemented through the Smith-Hughes Act, emphasized job-specific skills to the exclusion of the traditional academic curriculum. This particular focus was championed by Charles Prosser and David Snedden who advocated an essentialist approach toward vocational education, firmly grounded in meeting the needs of business and industry. Prosser believed that the purpose of public education in a democratic society was not for individual fulfillment but to prepare its citizens to serve society and meet the labor needs of business and industry. John Dewey, a pragmatist and progressive educator, disagreed with Prosser, arguing that education should be designed to meet the needs of individuals and prepare people for life in a democratic society. Prosser's views emerged in the Smith-Hughes Act and remained the dominant philosophic position until the 1960s.

Through a series of reauthorizations to the Smith-Hughes Act, from the 1920s through 1950s, new vocational-specific areas were added. The passage of the Vocational Education Act of 1963 (PL 88-210) signified a major change in federal policy and direction for career and technical education, from an exclusive focus on job preparation to a shared purpose of meeting economic demands that also included a social component. The dual themes of responding to economic demands for a trained workforce with marketable skills and social concerns for making vocational programs accessible to all students including individuals with special needs were firmly embedded in the Carl D. Perkins Vocational Education Act of 1984 (PL 98-524).

The two most recent reauthorizations of the 1984 Perkins legislation have made dramatic shifts in the direction of federal vocational education policy. "Both of these pieces of federal legislation are essentially grounded in school reform and the mandate to use federal funds to improve student performance and achievement" (Lynch, 2000 , p. 10). Thus, while economic and social concerns were still prominent themes, a third broad theme-- academics --emerged with passage of the Carl D. Perkins Vocational and Applied Technology Education Act of 1990 (PL 101-392, also called Perkins II ). While the commitment to special populations remained strong, it was tempered somewhat by the high level of publicity and effort devoted to increasing academic standards in vocational programs. Some educators believed this change in emphasis has signaled one of "the most significant policy shifts in the history of federal involvement in vocational-technical education. For the first time, emphasis was placed on academic, as well as occupational skills" (Hayward & Benson, 1993 , p. 3).

The most recent incarnation of the Carl D. Perkins Vocational and Technical Education Act (PL 105-332) was signed into law in 1998. Perkins III continues to emphasize improving academic achievement, and preparing young people for postsecondary education and work. The law also reaffirms the commitment to integrate academic and vocational education, serve special populations, tech prep (extensive articulation between secondary and postsecondary programs), accountability, and expand the use of technology. New initiatives enacted through Perkins III include the need to negotiate core performance indicators. Core performance indicators include things such as student attainment of identified academic and vocational proficiencies (state standards); attainment of a high school diploma or postsecondary credential; placement in postsecondary education, the military, or employment; and student participation in and completion of nontraditional training and employment programs (Lynch, 2000 ).

Philosophic perspectives of career and technical education. While the world has changed considerably from the early 1900s to the present in terms of work, family, and community, the basic philosophical arguments for and against various forms of vocational education have remained relatively the same. Two historical figures, Charles Prosser and John Dewey, have come to represent opposing positions on the nature of vocational education. Prosser's views on social efficiency, while lacking the qualities of a formal philosophic system (Miller & Gregson, 1999 ), posited that the major goal of school was not individual fulfillment but meeting the country's labor needs. A bulwark of social efficiency was the preparation of a well-trained, compliant workforce. To accomplish this goal efficiently, vocational education was organized and rigidly sequenced, an emphasis was placed on hands-on instruction delivered by people with extensive business-related experience, and program funding and administration occurred via a system that was physically and conceptually separate and distinct from academic education. While strongly supported by a majority of vocational education proponents at the time, Prosser's approach to vocational preparation has been criticized in recent years for being class-based and tracking certain segments of society--based on race, class, and gender--into second-class occupations and second-class citizenship (Lewis, 1998 ). Hyslop-Margison ( 2000 ) proclaimed that career and technical educators "must recognize that preparing students to fill lower strata occupational roles by providing them with instrumental skills and presenting the existing social paradigm as ahistorical, legitimates the class stratification and social inequality inherent in the present economic structure" (p. 28).

In sharp contrast, Dewey believed that the principle goal of public education was to meet individual needs for personal fulfillment and preparation for life. This required that all students receive vocational education, be taught how to solve problems, and have individual differences equalized.

Dewey rejected the image of students as passive individuals controlled by market economy forces and existentially limited by inherently proscribed intellectual capacities. In his view, students were active pursuers and constructors of knowledge, living and working in a world of dynamic social being. (Hyslop-Margison, 2000 , p. 25)

Dewey's work is recognized as a significant part of the philosophy known as pragmatism. In the last several decades, pragmatism has been identified as the predominant philosophy of CTE (Miller, 1996 ). Change and the reaction to it are significant features of pragmatic philosophy. "Change, after all, is among the greatest of philosophic certainties for the pragmatist. To accept and even embrace change is necessary for recognition as a philosophic pragmatist, either as an individual or as a field of practice" (Miller & Gregson, 1999 , p. 27). Pragmatic education prepares students to solve problems caused by change in a logical and rational manner through open-mindedness to alternative solutions and a willingness to experiment. The desired outcomes for pragmatic education are knowledgeable citizens who are vocationally adaptable and self-sufficient, participate in a democratic society, and view learning and reacting to change as lifelong processes (Lerwick, 1979 ). A number of current educational reform efforts such as applied academics, contextualized teaching and learning, integrated curriculum, and authentic assessment reflect Dewey's notion of pragmatism.

Miller and Gregson ( 1999 ) cogently argued that a proactive stance to change, in the profession and society, best reflects contemporary thinking in career and technical education and should be adopted. This position, known as reconstructionism, emphasizes the role of career and technical education in contributing solutions to problems such as discrimination in hiring, the class ceiling experienced by women and members of minority groups, poor working conditions, or the lack of viable job advancement opportunities. "The reconstructionist strand of pragmatism is explicit in that one of the purposes of vocational education should be to transform places of work into more democratic learning organizations rather than perpetuating existing workplace practices" (p. 30).

Impact of Educational Reform Efforts, 1980s-1990s

Since the publication of the report A Nation at Risk (National Commission on Excellence in Education, 1983 ) dozens of public and private studies, commissions, and task forces have convened for the purpose of reforming public education. Underlying most calls for reform is an assumption that the direction of causality for problems found in the economy, labor market, and workplace "runs a complex but direct path--from ineffective schools to increased social problems, loss of international competitive advantage, and high unemployment of youth" (Hartley, Mantle-Bromley, & Cobb, 1996 , p. 24). Schied ( 1999 ) explained that "recent calls for radical reform of vocational education rest on the spurious notion that the previous decade's economic decline was solely based on a failing educational system, thus, neatly avoiding corporate culpability in the U.S. economic decline" (p. xiii). Readers should interpret reform efforts using this critical perspective since the influence of external "stakeholders" has had substantial effect on current and projected educational reform efforts. Several of the more prominent and influential efforts are briefly examined.

The first wave of education reform seen in the 1980s started out with an exclusive focus on academic skills but gradually recognized that vocational preparation was essential if the U.S. was to be competitive in a technologically advanced global workplace. Around 1990 a second wave of educational reform emerged even as vocational education was in the midst of redefinition and establishing new directions. This phase of reform emphasized workplace basics, thrust into the spotlight with release of several high profile reports including America's Choice and the SCANS Report .

Overall, a number of consistent themes emerge from the myriad educational reform reports and initiatives advanced over the past several decades. Prominent themes include the integration of academic and vocational education; emphasis on developing general (transferable) work skills rather than focusing on narrow, job-specific work skills; articulation between secondary and postsecondary vocational programs; adjustments in programs to accommodate changing workforce demographics; preparation for a changing workplace that requires fairly high-level academic skills; familiarity and use of high technology; higher order thinking skills including decision-making and problem-solving; and interpersonal skills that facilitate working in teams. To this list of prominent themes, Hartley and colleagues ( 1996 ) identified basic skills they deemed necessary for success in the modern workplace, "learning to learn; (b) reading, writing, and mathematics; (c) communication; (d) problem solving; (e) personal/career development; (f) interpersonal skills; (g) organizational effectiveness; (h) technology; (i) science; and (j) family" (p. 39). These topics must be incorporated in any conceptual framework that reflects contemporary career and technical education.

Notions of the "New Economy"

Since the inception of public career and technical education in the early 1900s, economic developments have had major influences on the content and direction of curricula at secondary and postsecondary levels. Until recently, those developments have been gradual, fairly steady, and for the most part, predictable. However, over the past decade or so most economists and labor analysts have identified a new economy emerging in the U.S. and around the world (often referred to as globalization). While specifics about the new economy are sometimes in dispute, peoples' (e.g., Carnevale, 1991 ; International Labor Organization, 2001 ; Irons, 1997 ; Reich, 2000 ; U.S. Department of Labor, 2000 ) understanding of the emerging economy and expectations for the foreseeable future includes at least some of the following list of core characteristics.

- Manufacturers, spurred by advances in technology, maintain an accelerated level of growth in productivity. To stay viable, businesses are in a continual production mode. However, the emerging system of production is shifting away from high-volume mass production to high value production, from standardization to customization.

- Globalization of business markets results in substantial increases in competition for labor and goods. Competition is particularly keen for highly skilled workers, though not exclusively in computer and technology-related areas. The largest labor needs are for persons with innovative and creative methods for (a) producing new products and services, or (b) promoting and marketing these new goods and services to consumers.

- Information handling--e.g., storage, transfer, production--continue to increase in importance in the new economy. Low overhead costs require workers to be able to manipulate data and provide customized, rather than mass-produced, information and services.

- Business management practices are undergoing extensive restructuring and can be characterized by (a) continued downsizing, (b) a premium placed on personnel who can manage knowledge as opposed to people, and (c) an increasing reliance on outsourcing for most work. "Managers will become brokers/facilitators; there will be more technical specialists, more lateral entry, and shorter, flatter career ladders. Instead of the old-style division of labor into discrete tasks, job functions will converge, and work teams will consist of individuals who alternate expert, brokering, and leadership roles. Rewards will be based more on the performance of teams and networks" (Kerka, 1993 ).

- Fierce competition will affect both for-profit and not-for-profit institutions resulting in pressure to be innovative and to do it all better, faster, cheaper, and continuously. Restructuring will occur frequently in order to achieve the greatest efficiency and productivity.

What does all of this mean? Hawke ( 2000 ) observed that "the very essence of work has undergone a massive transition within the last decade and, for vocational education, this is having major implications" (p. 1). Robert Reich ( 2000 ), former U.S. Secretary of Labor, predicted that both work and family life will be affected by changes in the economic structure into the foreseeable future. To remain competitive, new enterprises must "continuously cut costs, lease almost everything they need, find the lowest-cost suppliers, push down wages of routine workers, and flatten all hierarchies into fast-changing contractual networks" (p. 6). The decentralization of decision-making and re-organization of work structures around semi-autonomous, task-oriented teams will be the norm.

Many of the implicit rules that have governed employment during the latter half of the 20th century--e.g., employees who expect steady work with predictably rising wages, (i.e., full-time, permanent, and for life), a clearly defined employer-worker relationship, and a clear separation between work and family--will no longer be in sync with the emerging reality of work (Hawke, 2000 ). Instead, Reich ( 2000 ) foresees the end of steady work, the necessity of continuous effort regardless of tenure or seniority status, and widening inequality in wages paid to top and lower-level workers. The new economy will require that workers possess a broad set of abilities that include both technical and interpersonal/communication skills. Higher order thinking skills such as decision making and problem solving, as well as flexibility, creative thinking, conflict resolution, managing information and resources, and the capacity for reflection will also be expected from workers of the future (Carnevale, 1991 ; Secretary Commission on Achieving Necessary Skills [SCANS], 1991 ).

Career and technical education stands poised to affect positive change in terms of support, preparation, and guidance in the areas of people's lives likely to be affected by changes in the new economy. However, to be relevant professionals must critically examine and modernize their underlying assumptions about the world of work and family life, and be willing to reconcile "the way we've always done things" with emerging directions of the economy and needs of the workforce as described in this section. To do otherwise, it seems, is to quickly relegate the profession to a footnote in the history of public education in the U.S.

Components of a Conceptual Framework

Past conceptual frameworks. Pratzner ( 1985 ) framed his discussion of the current (and emerging or alternative) paradigm in vocational education around six primary components: subject matter, beliefs in theories and models, values, methods and instruments, exemplars, and social matrices. The traditional paradigm, as Pratzner calls it, reflects an enterprise that serves the interests of employers, provides decontextualized instruction for specialized entry-level jobs, values job placement and earnings, follows a rigid, prescribed curriculum, uses norm-referenced and standardized tests to assess student learning, and has a considerable support network of professional associations and clubs.

More recently, Copa and Plihal ( 1996 ) challenged existing paradigms in vocational education, arguing for substantial change in career and technical education at both secondary and postsecondary levels. The authors believed that drastic changes occurring in all segments of society necessitated dramatic action. Rather than perpetuate the present form of career and technical education--"a collection of separate fields, each with a unique history and varying interrelationships over time" (p. 97)--they suggested a broad field approach to curriculum integration where career and technical education is offered to students as a comprehensive subject for learning about work, family, and community roles and responsibilities. A broad field of study curriculum for career and technical education teacher education would emphasize the "study of work, family, and community as a composite of vocational roles and responsibilities. . . . Next, the course of study could become more specialized as teacher education candidates elect a specialization" (p. 109) and sub-specializations in areas such as (a) human development, (b) the family, (c) technology and technological change, or (d) distribution of power and authority encountered in families, at work, and in the community.

A major advantage of the approach advanced by Copa and Plihal ( 1996 ) is that "the separate fields structure does not respond well to the changing nature of work, family, and community responsibilities. . .[and] more importantly, the separate fields structure fails to recognize the growing importance of the interaction among work, family, and community responsibilities and interests" (p. 103). A major drawback to acceptance of Copa and Phlihal's proposal is that career and technical education would need to be totally reconceptualized with the likelihood that firmly established (entrenched ?) traditions, organizations, and structures would give way to new ones built on the principles of one broad field of study. While these changes could provide career and technical education with a focus needed to address emerging issues related to work, family, and community, it is doubtful that a wholesale change will occur.

Grubb ( 1997 ) advocated a shift from job-specific vocational preparation to a more generic, academic-based approach similar to Dewey's notion of education through occupations. Four general practices framed Grubb's idea of the new vocationalism . First, he maintained that the purpose of secondary occupational curricula should be more general in nature rather than job specific. This change would allow students to pursue several possible career options simultaneously rather than being required to choose between college or vocational curriculum tracks. Second, in terms of curriculum, traditional academic content would be integrated into occupational courses while occupational applications and examples would be integrated in academic courses. Third, education through occupations would require a different school (institutional) structure designed to encourage curriculum integration such as the use of career academies or school-within-a school designs using career clusters as organizing themes. Fourth, several other elements included (a) the availability of various work-based learning activities such as job shadowing and short-term internships, school-based enterprises, cooperative education, and placements governed by occupational licenses or certificates of mastery, (b) a hierarchical connection of educational and training opportunities in secondary programs and between secondary and postsecondary programs (i.e., tech prep), and (c) use of applied teaching methods and team-teaching strategies that are more contextualized, more integrated, student-centered, active (or constructivist), and project- or activity-based.

Lynch ( 2000 ) describes a "new vision" for career and technical education that supports emerging aspects of the new vocationalism. Four major themes were proposed, including to (a) infuse career planning and development activities throughout the education process; (b) embed career and technical education reform within the broad context of general education reform; (c) develop contemporary programs based on the needs of business and industry, and (d) institute a K-14 education model where all students are prepared for postsecondary education. Six components are also outlined in Lynch's framework emphasizing both student achievement and school reorganization. They are to (a) organize programs around major fields of study; (b) use contextual teaching and learning; (c) infuse work-based learning contributing to mastery of industry standards; (d) use authentic assessment, (e) increase use of career academies, and (f) implement successful models of tech prep.

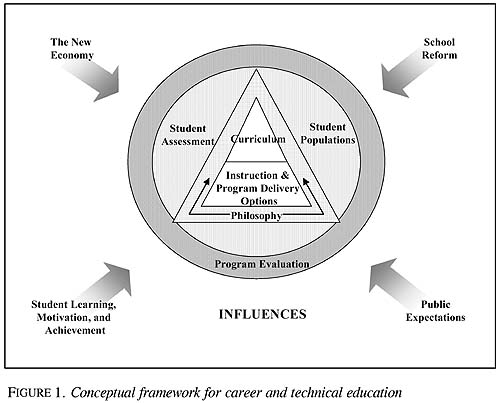

A proposed contemporary framework. With the exception of the several frameworks presented here, few descriptive frameworks for career and technical education exist. However, much if not all of the information needed to develop a coherent perspective of the field, both present and near future, is available through various sources such as legislation, descriptions of the work place and work force, research, opinion and everyday practice. Construction of the framework presented here has capitalized on this information in an effort to synthesize and reflect current streams of thought and practice rather than devise a new vision designed to take career and technical education into the next millennium. The conceptual framework for career and technical education I propose is offered as a graphic illustration of the relationship of major components that shape the field (see Figure 1). While relationships between various components are given, the major function of the diagram is to serve as a starting point for discussion about the conceptual underpinnings of the field.

Major components of career and technical education are represented by five categories: curriculum, instruction and delivery options, student assessment, clientele, and program evaluation (accountability). Philosophy, whether implicit or explicit, provides the motivation and impetus for actual practice and affects all areas. The influence of internal and external forces on the field such as the new or emergent economy, educational reform initiatives, student learning, and the expectations of society for career and technical education are recognized.

Current (and Future) State of Career and Technical Education

Curriculum. Curriculum reflects the state of the field; what is considered important, what is being taught (content or conceptual structure), and how it is taught (process; Lewis, 1999 ). Discussions surrounding required curriculum components have shifted debate from a narrowly defined set of academic abilities toward a broader set of academic or general competencies, technical and job specific skills, interpersonal abilities, and behavioral traits, including motivation. Perkins III places strongest emphasis on three core curriculum issues that are representative of the new vocationalism: (a) integration of academic and career and technical education, (b) articulation of secondary and postsecondary programs, and (c) connections between school and the world of work.

Results of school reform initiatives, legislation, and changes in the workplace provide the ideal platform to consider moving, at least some, of career and technical education to a common core called workforce education . If the field eventually moves toward workforce education as "the unifying conceptual framework for vocational education [it] will inevitably mean a need to redefine vocational education standards independent of content areas" (Hartley et al., 1996 , p. 45). Kincheloe ( 1999 ) described a "pedagogy of work" which consisted of a common core of knowledge about the world of work based on a critical perspective including an examination of the social, economic, historical, and philosophical foundations of work such as the nature of work and the economy, the social impact of technology, the power of cultural representations, and the ethics of business and industry.

Educational reform efforts have, undoubtedly, influenced the shape of career and technical education curriculum. While not uniform, the new curriculum is likely to be contextually-based and grounded on the need for students to demonstrate mastery of rigorous industry standards, high academic standards and related general education knowledge, technology, and general employment competencies (Lynch, 2000 ).

A persistent challenge faced by career and technical educators revolves around the question of whether programs should be occupation specific, stressing depth of preparation, or have a broad-based or occupational cluster orientation that stresses breadth of preparation. In this regard, both ETO [employment through occupations] and traditional/tech prep advocates agree that the objective should be breadth not depth. (Gray, 1999 , p. 165)

Career and technical teacher education programs should be guided by the overall mission(s) and standards established by the field (see Table 1).

Instruction/delivery options. Biggs, Hinton, and Duncan ( 1996 ) asserted that major changes in the educational infrastructure are necessary to support and build a quality work-preparation system for the 21st century. And, a number of contemporary teaching innovations have emerged or assumed a greater role in career and technical education including tech prep, integrated curriculum, cognitive- and work-based apprenticeship, career academies, school-based enterprises, and cooperative education. Table 2 provides a summary of these approaches to teaching and learning. Each approach requires new methods of pedagogy to accommodate teachers' emerging roles as collaborators, facilitators of learning and as lifelong learners; familiarity with the workplace; and ability to make school settings reflect workplace environments (Naylor, 1997 ).

Student assessment. The emphasis of many educational reform initiatives on higher order thinking skills such as problem-solving, critical thinking, reasoning, and so forth, and expressed dissatisfaction with conventional testing approaches demands that different approaches to assessing student learning be implemented (Johnson & Wentling, 1996 ). Most educators refer to this new form of student evaluation as authentic, or performance-based, assessment. Authentic assessment has three fundamental goals: reforming curriculum and instruction; improving teacher morale and performance; and strengthening student commitment and capacity for self-monitoring (Inger, 1993 ). At its core, authentic assessment is a reaction to the deficiencies perceived in traditional approaches to testing. It requires students to demonstrate their grasp of knowledge and skills by creating a response to questions or a product that demonstrates understanding (Wiggins, 1990 ). This type of assessment reflects the complexities of everyday life and a belief that learning is actively constructed knowledge influenced by context (Kerka, 1995 ).

A variety of options are available to for conducting authentic assessments including portfolios; exhibitions; checklists; simulations; essays; demonstrations or performances; interviews; oral presentations; observations; and, self-assessment. Rubrics, scoring devices that specify performance expectations and various levels of performance, are used to establish benchmarks for documenting progress and provide a framework for ensuring consistency (Kerka, 1995 ).

Clientele. While the historic roots for vocational education were in providing job-specific training to working class (noncollege-bound) youth, the contemporary world of work requires few of the manual job skills required a century ago. Today, ample evidence shows the work skills required in the 21st century include higher-order thinking skills (reasoning, decision-making, problem-solving), flexibility, interpersonal skills, and technological literacy. Not only are cognitive skills in demand, but many jobs now require some type of postsecondary education (less than a baccalaureate degree) for entry-level.

Given this scenario, many professionals are asking, "Whom should CTE serve?" Has the clientele for career and technical education shifted away from work-bound youth to those adolescents who don't attend a four-year college or university but receive some type of postsecondary education at a technical or community college? Should secondary career and technical education be charged with providing job-specific training to students not attending some form of postsecondary education? At present, few answers exist.

Currently, career and technical education programs serve several primary functions ranging from integrated academics instruction to tech prep to job preparation for employment-bound and educationally disadvantaged youth. These diverse goals aim to achieve very different ends and are often at odds with one another. Lynch ( 2000 ) suggests that upwards of one-third of all secondary students enrolled in career and technical education programs are not college-bound. Another 8-12 percent of students are identified as being educationally disadvantaged. Both of these groups require job-specific preparation to transition from school to adult life. However, recent trends to promote articulated secondary-postsecondary programs may overlook this substantial proportion of program enrollees. And, when services are available, they are often relatively low, entry-level job skills that offer limited job entry or advancement opportunities.

A number of unanswered questions remain for the field to tackle as ongoing reform efforts of career and technical education curriculum occur. How will current and future reform initiatives and subsequent changes to career and technical education programs affect students with special needs? How do raised academic standards and the increasing need to attend some type of postsecondary education affect special populations and work-bound youth? Should there be a high school career and technical education option that focuses solely on job-specific training? If so, can a program based at the secondary level provide high-skills/high-wage jobs?

Program evaluation. Accountability has become a hallmark of educational reform initiatives and has not escaped reform efforts in career and technical education. Perkins III legislation requires that states develop evaluation systems to assess four core indicators of student performance including academic and vocational achievement, program completion, successful transition from school to postsecondary education and/or employment, and accessibility and equity. Although program evaluation is mandated, criticisms exist about the criteria and methodology used to collect data, and the usefulness of evaluation results (Halasz, 1989 ). Indeed, collecting data to respond to these federal mandates can pose considerable challenges. Gray ( 1999 ) notes that traditional outcome assessment measures--job and college placement rates--still dominate the criteria used to evaluate the effectiveness of career and technical education programs.

Practitioners also face substantial challenges in determining what state and local evaluation criteria (indicators) will be used, the specific data needed to reflect these criteria, methods of collecting it, and how to use it once collected. Some of the questions that require attention include: How is program quality defined? How should student outcomes or learning be measured? How will students enrolled in career and technical education course or programs be classified? What approach will be used to measure instructional practice? How will teacher quality be defined and measured?

Given current mandates and future projections, a conceptual framework in career and technical education must include performance indicators that examine legislative mandates and underlying philosophy, as well as specific outcomes, practices, and inputs. Halasz ( 1989 ) indicated that school culture and stakeholders' needs must also be considered. "A variety of information should be collected (personal, instructional, institutional, societal, and so on) from multiple sources (teachers, students, administrators, parents) using multiple methods (survey, interview, participant observation, historical, archival)" (¶ 9). One challenge to CTE teacher educators is to provide emerging teachers with the knowledge required to develop, implement, and maintain appropriate accountability systems.

Summary, Conclusions, and Future Steps

Most career and technical teacher educators acknowledge the need to revisit the basic assumptions, conceptual framework, and syllabi of existing pre-service programs. Indeed, the entire profession must be willing and able to engage in ongoing examination of issues that contribute to a dynamic and relevant conceptual framework, e.g., philosophy, workplace demands, and skill requirements. The field's best thinking must be integrated into teacher preparation programs and, subsequently, into secondary and postsecondary classrooms comprised of a diverse clientele within the context of an increasingly sophisticated work place characterized by a global economy where success is directly tied to work force readiness, the rapidly changing nature of jobs and required work skills, and increasing role of technology in the performance of work tasks (Lewis, 1997 ).

But, what exactly should teacher preparation programs prepare emerging teachers to do? Table 3 summarizes the main components of conceptual frameworks for career and technical education--past, present, and future. Historically, the conceptual framework of career and technical education has revolved around specific job training, clear distinctions between academic and vocational education, and preparing adolescents to transition from school directly to work. Curriculum and instructional approaches relied heavily on an essentialist philosophy where students were viewed as products and taught in ways that reflected the industries they were being prepared to enter.

In sharp contrast, the emerging conceptual framework reflects efforts at local, state, and national levels "to broaden vocational education--integrating the curriculum more closely with rigorous academics, improving articulation to postsecondary education (two-year and four-year), and stressing long-term preparation for productive careers that will be subject to increasing technological change and economic reorganization" (Hoachlander, 1998 , ¶ 1). Secondary career and technical education programs will continue a trend that focuses less on specific training for immediate entry-level employment upon graduation. Rather, secondary programs will provide more general knowledge about the workforce, offer career awareness and exploration activities in specified career clusters, nurture higher-order thinking skills development, and support students in making initial decisions about their career goals and plan postsecondary activities necessary to achieve those goals. Postsecondary education, on the other hand, will remain in the best position to prepare students for specific jobs.

Implications for CTE Teacher Education and Teacher Education Programs

What then are the implications of the proposed conceptual framework for career and technical teacher education programs? In a word, they are substantial. While myriad other arrangements or contextual structures can address the question of specific content to include or exclude teacher education programs, a relatively simple, straightforward approach focuses on the types of instructional content needed in three areas: general workforce education, content area specialties, and professional teaching development. These areas are broad enough to incorporate issues recognized as integral to the emerging vocationalism (see Table 4).

General workforce education. Aspects of teacher preparation curricula that focus on general workforce education assume that a substantial portion of the knowledge and experiences that define career and technical education cross specialty area boundaries. A common core of knowledge about the world of work is assumed stressing topics like the function of work and family life in society; economics and systems of production and distribution; cultural aspects of work, the family, and society; development and application of higher-order thinking skills, employability skills, and job seeking skills. The nature and underlying assumptions of general workplace education topics suggest an integrative approach to instruction where students from all vocational specialty areas are grouped together for classes. This approach should not only help emerging career and technical educators understand the need for a broad-based curriculum focus, but also nurture a sense of professional commonality and shared purpose.

Content area specialty. The clustering concept adopted by the U.S. Department of Education, the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards ([NBPTS], 2001 ) and others reflects an ongoing effort "to organize the economy into coherent sectors that will facilitate the development and implementation of a national skills standards system" (p. 4). Regardless of the specific structuring system used, some form of content area specialization will, in all likelihood, persist for career and technical education. While maintaining some aspect of "traditional" vocational education, emerging teachers will increasingly be exposed to something other "than business as usual."

Teacher preparation curricula need to equip preservice teachers with the tools and experiences necessary to integrate academic and vocational education, prepare students for entry into the workforce, and support the successful transition of students from high school to two-year or four-year postsecondary education. Regardless of the specific curricula and structure of teacher preparation programs, all must satisfy three essential requirements: They must prepare emerging educators to (a) address the long-term prospects of students not just entry-level jobs, (b) encourage high levels of academic proficiency and mastery of sophisticated work-based knowledge and skill, and (c) preserve the full range of postsecondary options for program participants (Hoachlander, 1998 ). No small task.

Professional teaching sequence. Career and technical educators must be able to incorporate an array of possible teaching strategies in classroom, laboratory, and work-based settings. Traditional teaching approaches will need to be supplemented with greater emphases on emerging pedagogical approaches like integrating of academic and vocational education, tech prep, and contextualized teaching and learning forums. Knowledge about the diversity of students and school settings will continue to be a critical element in adequate teacher preparation and will need to expand in scope. Attention will also need to be paid to assessment issues, most notably high stakes testing and accountability issues related to school reform efforts. Ramsey, Bodilly, Statsz, and Eden ( 1994 ) wrote that "teachers also need to be trained in the use of teaching techniques that support activity-based learning, including hands-on experiences, problem-solving, cooperative or team-based projects, lessons requiring multiple forms of expression, and project work that draws on knowledge and skills from several domains."

Given the nature of changes to career and technical education curriculum, the professional teaching sequence of courses should be delivered in a mixed student environment. Like the topics contained in the general workforce education segment of the curriculum, pedagogical knowledge and skills are not unique to any one vocational specialty area. In fact, preservice teachers can benefit from the different perspectives attributed to various specialty areas.

Role of teacher educators. Successful implementation of recommended changes to career and technical teacher education programs, as well as the field as a whole, requires a recognition of the slow and difficult process of reform. Teacher educators must be especially aware of and understand how to successfully negotiate the change process. A strong effort should ensure that emerging teachers are aware of workplace inequities and be able to change them when possible.

To bridge the, sometimes, considerable gap between cutting-edge thinking and current practice teacher educators can facilitate programmatic change at both regional and national levels, serving as liaisons between what is and what should be . Otherwise, the academy may prepare emerging teachers to (a) understand a new career and technical education but be ill-prepared to cope with current classrooms reflecting traditional practice, or (b) be wholly prepared for traditional curriculum and school environments but lack an understanding or ability to implement emerging issues and practices.

Final Words

Using the historical record to identify issues and direction for developing a conceptual framework of career and technical education reveals how little the field has actually evolved, at least in terms of philosophical, conceptual, and theoretical underpinnings, from its inception to the present. While this situation is beginning to change with the development of tech prep and academic-vocational integration models and so forth, many of the same positions, issues, and arguments for and against school-based occupational preparation common around the time of the Smith-Hughes Act of 1917 are still common in contemporary writings. Examples of other types of perennial issues that will influence career and technical education include:

- Who should be served by career and technical education? Cliché and rhetoric must be discarded in favor of sound thoughtful positions that are implemented and successful rather than merely spoken.

- Will career and technical educators embrace democratic education principles espoused by John Dewey where students are taught to critically analyze work and participate in society, or passively accept the status quo where workers are often exploited by industry (Kincheloe, 1999 ).

- What should the nature of career and technical education be at the secondary level? postsecondary level? Should secondary programs reflect a broader type of workforce education or should other alternatives--e.g., specific job training for work-bound and disadvantaged youth or education through occupations (Grubb, 1997 )--be implemented?

At the dawn of a new century, it seems appropriate to take stock in the future of career and technical education. Many authors have contributed to an on-going dialogue about the nature of contemporary and future career and technical education. Ideas and options have been proposed, articulated, and studied. Yet, action is slow. The development of any conceptual framework is of little value if action does not result. Collectively, the field must be willing to tackle tough questions and debate potentially contentious issues delineated in the professional literature to arrive at and then maintain a clear and concise framework. Such a framework can guide funding priorities, program development, classroom instruction, and relationships with external constituencies. To do otherwise runs the risk of glossing over fundamental issues and concerns, repeating the same arguments and issues for another century, or perhaps worst of all, allowing others (e.g., federal and state government, funding agents, business and industry leaders) to make decisions for the field.

Endnotes

1 The terms vocational education and career and technical education are used interchangeably. However, references to historic events or thought use "vocational education" in an attempt to preserve the integrity and intent of past authors' work.

References

Biggs , B. T., Hinton, B. E., & Duncan, S. L. (1996). Contemporary approaches to teaching and learning. In N. K. Hartley & T. L. Wentling (Eds.), Beyond tradition: Preparing the teachers of tomorrow's workforce (pp. 113-146). Columbia, MO: University Council for Vocational Education.

Carnevale , A.P. (1991). America and the new economy . Alexandria, VA: American Society for Training and Development. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED333 246)

Copa , G. H., & Plihal, J. (1996). General education and subject matter education components of the vocational teacher education program. In N. K. Hartley & T. L. Wentling (Eds.), Beyond tradition: Preparing the teachers of tomorrow's workforce (pp. 91-112). Columbia, MO: University Council for Vocational Education.

Gray , K. (1999). High school vocational education: Facing an uncertain future. In A. J. Paulter, Jr. (Ed.), Workforce education: Issues for the new century (pp. 159-169). Ann Arbor, MI: Prakken.

Grubb , W. N. (1997). Not there yet: Prospects and problems for "Education through Occupations." Journal of Vocational Education Research, 22 , 77-94.

Halasz , I. M. (1989). Evaluation strategies for vocational program redesign [ERIC Digest No. 84]. Columbus: The Ohio State University, ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult, Career, and Vocational Education. Retrieved from http://ericae.net/db/edo/ED305497.htm

Hartley , N., Mantle-Bromley, C., & Cobb, R. B. (1996). Building a context for reform. In N. K. Hartley & T. L. Wentling (Eds.), Beyond tradition: Preparing the teachers of tomorrow's workforce (pp. 23-52). Columbia, MO: University Council for Vocational Education.

Hawke , G. (2000, July 20). Implications for vocational education of changing work arrangements [Professional Development Speaker Series]. Columbus: The Ohio State University, National Centers for Career and Technical Education. Retrieved from http://www.nccte.com/events/profdevseries/0000720geofhawke/index.html

Hayward , G. C., & Benson, C. S. (1993). Vocational-technical education: Major reforms and debates 1917-present . Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Office of Vocational and Adult Education. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 369 959)

Hoachlander , G. (1998). Toward a new framework of industry programs in vocational education . Berkeley, CA: MPR Associates. Retrieved from http://www.ed.gov/pubs/FrameworkIndustry/bodytext1.html

Hyslop -Margison, E. J. (2000). An assessment of the historical arguments in vocational education reform. Journal of Career and Technical Education, 17 , 23-30.

Inger , M. (1993, March). Authentic assessment in secondary education. IEE Brief, 6 . New York: Columbia University Teachers' College, Institute on Education and the Economy. Retrieved from http://www.tc.columbia.edu/~iee/BRIEFS/Brief06.htm

International Labor Organization [ILO]. (2001). World employment report 2001: Life at work in the information economy . Geneva, Switzerland. Retrieved from http://www.ilo.org/public/english/support/publ/wer/overview.htm

Irons , J. (1997). Readings on the "New Economy." Retrieved from http://www.economics.about.com/library/weekly/aa021198.htm

Johnson , S. D., & Wentling, T. L. (1996). An alternative vision for assessment in vocational teacher education. In N. K. Hartley & T. L. Wentling (Eds.), Beyond tradition: Preparing the teachers of tomorrow's workforce (pp. 147-166). Columbia, MO: University Council for Vocational Education.

Kerka , S. (1993). Career education for a global economy [ERIC Digest]. Columbus: The Ohio State University, ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult, Career, and Vocational Education. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED355 457)

Kerka , S. (1995). Techniques for authentic assessment [Practice Application Brief].Columbus, OH: ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult, Career, and Vocational Education. Retrieved from http://ericacve.org/docs/auth-pab.htm

Kincheloe , J. L. (1999). How do we tell the workers? Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Lerwick , L. P. (1979, January). Alternative concepts of vocational education . Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, Department of Vocational and Technical Education, Minnesota Research and Development Center for Vocational Education. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 169 285)

Lewis , T. (1997). Editorial. Journal of Vocational Education Research, 22 , 73-76.

Lewis , T. (1998). Toward the 21st century: Retrospect, prospect for American vocationalism (Information Series No. 373). Columbus: The Ohio State University, ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult, Career, and Vocational Education.

Lewis , T. (1999). Content or process as approaches to technology curriculum: Does it matter come Monday morning? [Electronic version]. Journal of Technology Education, 11 (1), 1-16. Retrieved from http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/ejournals/JTE11n1/lewis.html

Lynch , R. L. (2000). New directions for high school career and technical education in the 21st century (Information Series No. 384). Columbus: The Ohio State University, ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult, Career, and Vocational Education.

Miller , M. D. (1996). Philosophy: The conceptual framework for designing a system of teacher education. In N. K. Hartley & T. L. Wentling (Eds.), Beyond tradition: Preparing the teachers of tomorrow's workforce (pp. 53-72). Columbia, MO: University Council for Vocational Education.

Miller , M. D., & Gregson, J. A. (1999). A philosophic view for seeing the past of vocational education and envisioning the future of workforce education: Pragmatism revisited. In A. J. Paulter, Jr. (Ed.), Workforce education: Issues for the new century (pp. 21-34). Ann Arbor, MI: Prakken.

National Board of Professional Teaching Standards [NBPTS]. (2001). Career and technical education standards . Arlington, VA: Author.

National Commission on Excellence in Education. (1983). A nation at risk: The imperative for reform . Washington, DC: Author. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 251 622)

Naylor , M. (1997). Vocational teacher education reform [ERIC Digest No. 180]. Columbus: The Ohio State University, National Center for Research in Vocational Education. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 407 572)

Pratzner , F. C. (1985). The vocational education paradigm: Adjustment, replacement, or extinction. Journal of Industrial Teacher Education, 22 (2), 6-19.

Ramsey , K., Bodilly, S. J., Stasz, C., & Eden, R. (1994). Integrating academic and vocational education: Lessons from eight early innovations. Berkeley, CA: RAND. Retrieved from http://www.rand.org/publications/RB/RB8005

Reich , R. (2000). The future of success . New York: Knopf.

Sarkees -Wircenski, M., & Scott, J. L. (1995). Vocational special needs (3rd ed.). Homewood, IL: American Technical.

Schied , F. (1999). Foreword. In J. L. Kincheloe, How do we tell the workers? (pp. xii-xiii). Boulder, CO: Westview.

Secretary's Commission on Achieving Necessary Skills [SCANS]. (1991). What work requires of schools: A SCANS report for America 2000 . Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 332 054)

US . Department of Labor. (2000). Futurework: Trends and challenges for work in the 21st century . Retrieved from http://www.dol.gov/dol/asp/public/futurework/execsum

Wiggins , G. (1990). The case for authentic assessment. ERIC Digest. Washington, DC: American Institutes for Research, ERIC Clearinghouse on Test Measurement and Evaluation. Retrieved from http://www.ed.gov/databases/ERIC_Digests/ed328611.html

JAY W. ROJEWSKI is Professor in the Department of Occupational Studies, University of Georgia, 210 River's Crossing, Athens, GA 30602. e-mail: rojewski@uga.edu