ALAN v29n3 - An Interview with Author/Screen Writer David Klass

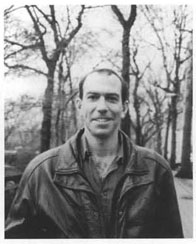

An Interview with Author/Screen Writer David Klass

Sissi Carroll

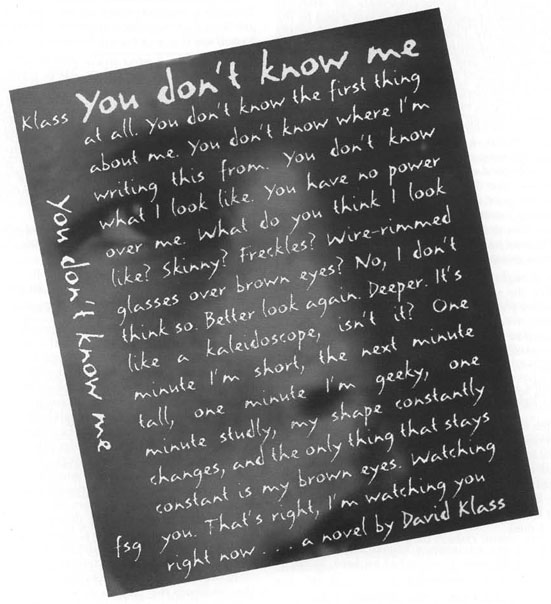

Author David Klass caught my imagination and attention years ago with his Wrestling with Honor (Dutton 1988) and California Blue (Scholastic 1994), each of which raises serious, thought-provoking questions about sports, ethics, human values, and complex father-son relationships—traits that, 1 later learned, are characteristics of Klass's YA fiction. And now, it seems possible that John, the protagonist and narrator of David Klass's You Don't Know Me (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2001), might dethrone Holden Caufield as the voice of adolescents.

I had the privilege of engaging in a telephone interview with David Klass in January, 2002. When we initially spoke in order to arrange the interview, one of his first questions for me was, "So, do you know about my dual role as writer for young adults and for Hollywood?" 1 admitted my ignorance about the Hollywood connection, then began doing some serious homework. A few weeks later, during the interview, 1 quickly realized that the dual role as YA author and Hollywood screenwriter is only one of the many rich surprises 1 would learn about David Klass, the author-author.

The First Surprise

David Klass is one of the humblest and most gracious men with whom 1 have ever had the pleasure to speak. He is eager to downplay his own accomplishments and to praise those who have had a positive impact on his life, especially his father, mother, sisters, wife, and infant son. Despite his success as the author of some of the most compelling books in young adult literature, including Wrestling with Honor, California Blue, You Don't Know Me , and his newest, Home of the Braves (to be released by Fararr, Straus and Giroux in the spring, 2002), and his success as a Hollywood screenwriter of blockbuster films including Desperate Measures (1998), starring Michael Keaton and Andy Garcia, and Kiss the Girls (1997), starring Morgan Freeman and Ashley Judd, and collaboration with his sister Perri Klass on an ABC Movie of the Week, Runaway Virus (2000) and collaboration with his sister Judy Klass on a Showtime Original Movie for television, In the Time of the Butterflies (2001), David Klass refuses to boast. (I think 1 would constantly wear a t-shirt that announced: "Brilliant and Successful Writer" if I had his resume.) While he recognizes that he has become a successful writer in two disparate worlds—Hollywood and young adult literature—he shrugged off my amazement by saying that he has merely been exceedingly "fortunate". And he added, "There are a lot of people 1 knew in Los Angeles who are a lot more talented that 1 was or am who, for one reason or another, have been unable to crack through and are still trying, 10 years after I left."

Klass credits his mother, Sheila Solomon Klass, a now-retired professor of English and author of seventeen novels, including popular YA titles A Shooting Star: A Novel about Annie Oakley (BDD, 1998) and The Uncivil War (Bantam, 1999) as his professional role model. It was she who demonstrated what a writer does, for her son, by awakening him to the sound of her typewriter each morning before the family started its day. He modeled her self-discipline when he arose at 5 a.m. each morning in Atami, Japan, to write what would become his first novel, The Atami Dragons (Macmillan 1984).

While is it clear that his mother plays a significant role in his life as a writer and as a human, Klass is also eager to credit his late father for urging him to write, even at times when the writing seemed stalled or impossible. He refers to his father, who served as Chair of Anthropology at Barnard College and taught there for over thirty years, as his "best reader." He remembers that his father read to the Klass children every night; Treasure Island was a family favorite. Klass cites the following as specific evidence of his father's influence on his work: When writing You Don't Know Me , Klass felt that he was trying to do the impossible—giving narrator John a comic voice, yet placing him in a horrific situation. Sure that the book was hopelessly flawed, Klass put it aside. It was his father who assured him that a character like John needed to be written. The elder Klass reminded his son that humor is John's way of escaping pain, and that through humor, John is "able to get a different look at the world." With that encouragement and perspective, Klass was able to return to the manuscript and complete the novel. Although his father died in the spring, 2001, "his presence lives large" in his son's work and life.

Klass is also noticeably proud of his sisters, with good reason. Perri Klass is a medical doctor who writes nonfiction for the New York Times and who has won five O. Henry awards for short stories. She is also the Director of Reach Out and Read, a literacy program in the Boston area. Judy Klass is a playwright with whom he has collaborated, most recently on the Showtime movie, In the Time of the Butterflies . With all of that brain power concentrated in a single family, I had to ask Klass what a holiday celebration is like when his clan gets together. He admitted, "It can be pretty intellectual," then added, with a laugh, "It is no wonder that I never thought I could keep up. I guess that I got into sports as a way to distinguish myself." Klass confesses that it was competition with his sister that led to his first publication: Perri had submitted short stories to Seventeen magazine, and they were published. When that magazine ran a short story contest, David, then a high school student, entered it—and won.

Throughout our conversation, David Klass deftly deflected praise away from himself—and heaped it onto members of his family and others. I was surprised to learn that he is unabashedly proud of, and close to, his family, and that he is humble and generous as an artist.

The Second Surprise

David Klass, the prolific and powerful writer who studied with John Hersey at Yale, did not intentionally set out to write either novels or screenplays. This is the story of how he happened to write his first novel, an event that had an immediate impact on his entree into the film industry as a screenwriter:

After he graduated from Yale with a degree in history, he spent a year working as a clerk in a law firm in Washington, D.C.. There, he felt like a glorified file room attendant; the windowless room in which he worked made him long for "an adventure". After a year, he enlisted in a program sponsored by the Japanese Ministry of Education. In the program, 800 Americans were chosen to go to Japan, where they would be expected to teach English. Although he had no background in teaching, he signed up, and was sent, as fortune had it, to the "beautiful wonderful resort town" of Atami, less than an hour from Tokyo by bullet train.

Klass as Teacher

As the first American to go to Atami to teach, he was treated as an honored guest. The mayor held a press conference upon his arrival, and, since the mayor knew that Americans are used to large houses, Klass was given the use of a three-bedroom apartment, a size that is an almost unheard-of luxury in Japan. His apartment overlooked the bay; it was in that idyllic setting that he lived for the two years of his Atami assignment. He taught adolescent students in the equivalent of American junior high school and high school classes three days per week (all of his students had studied English for years), then traveled into the mountain and island towns to teach two days per week. For someone who had left a position as a law clerk in a windowless office, seeking adventure, he was certainly living a dream. Klass soon understood that he was treated with honor not only because he was an American who was there to work, but because he was a teacher. According to Klass, all of Atami's public school teachers were afforded the kind of respect that American teachers would call "amazing." As an example, he noted that the townspeople would "rarely even allow" him to pay for a meal. He commented, too, that "the mayor, police chief, and the principal of the high school were the most respected people in town." Klass summarizes his impression of Atami and its people by stating, simply, "It knocked me out."

Klass as Writer of YAL

On the first night of his arrival in Atami, Klass sat down and began writing a story about an American boy who played baseball, and who wanted to climb Mt. Fuji. The story became The Atami Dragons . When I asked if he knew that he was writing a "young adult book" from the beginning, Klass admitted that he was not focused on writing for the genre exclusively, though the fact that he felt comfortable with "the length and size" of adolescent novels appealed to him. He added, laughing, that he also had, at the time, "the advantage of being a 23-year-old with the maturity level of a 17 year-old." Before Christmas of that first year in Japan, he finished the novel, and sent it to Scribners. Why Scribners? Klass explains, "I knew that it was the company that had published Fitzgerald and Hemingway, so I figured they knew something about getting books published." He was right; the book was published when Klass was still in Atami. I can only imagine that his popularity as a local celebrity, due to his role as a school teacher, skyrocketed when the title "author" was added to his name.

Klass as Hollywood Screenwriter

On the eve of his 25 th birthday, Klass was surprised with a call from out of the blue—or close to it. After celebrating his birthday with his Atami friends, Klass returned home in the wee hours of the morning, where he received an unexpected telephone call from a person in Hollywood. The caller informed him that someone had bought the option to make The Atami Dragons into a movie. The potential producer was, coincidentally, traveling in Japan, and Klass was asked to pick him up to show him around Atami. There was the possibility that some of the film would be shot in the town for which Klass had developed a deep affection. When I asked him if his reputation shot even higher with the news got around that a Hollywood producer was in town because of him, Klass explained, graciously, that he was reluctant to have the world of Hollywood burst into Atami, since Atami had "become sacred" to him. The presence of a Hollywood producer, one who constantly looked for features of the resort town that would serve as advantages for a feature film, made Klass uncomfortable. He offered, as an example of his discomfort, an incident in which the movie producer, upon meeting the highly respected high school principal, showed his lack of regard for the principal's reputation and standing by asking, immediately, "Can you act?"

Despite his lack of knowledge about Hollywood, Klass was up for a new challenge and adventure. He decided to take a leap; his teaching assignment in Atami completed, Klass moved to Los Angeles, expecting that The Atami Dragons project would allow him to break into the film industry as a successful screenwriter. The project failed, as Klass says most do—most often "for reasons that have nothing to do with the writer, like the producer getting a new job, or divorcing the director, or someone writing a similar story that gets picked up." Klass describes the next seven or eight years, ones he spent in Los Angeles, as difficult, lonely ones. He re-discovered a lesson that he had learned while in Washington D.C.: it is tremendously difficult to break into the big time without family connections or a great stroke of luck. As Klass admits, his family is an intellectual powerhouse, but it had no connections in Hollywood. Even his stellar education and his quick success as an author carried little weight there. Nevertheless, Klass tried everything he could to break into the industry: he completed a degree in directing at the University of Southern California's acclaimed cinema school. He continued to write screenplays, but he discovered another truth hidden in Hollywood: "many screenwriters keep working for years, and even make a decent living, but never have scripts that get produced." He was persistent, yet by his admission, he was "terrible at schmoozing," and his entry into the film world was a long, painful struggle.

Finally, with his idea for a screenplay called Desperate Measures , Klass made his mark in Hollywood. The screenplay was made into a major motion picture starring Michael Kearon and Andy Garcia. The director/producer, Barbet Schroeder, decided that Klass should be replaced by a writer with more experience once the cast had been hired and filming had begun, and a team of nine writers was hired to revise his original script. Nevertheless, Klass ultimately received credit as the sole author of the movie, the writer with the "major vision" for the movie.

His wonderful achievement as a screenwriter was tinged with a few other mildly dark moments, as well. When I asked him if he was happy with the movie once it was complete, he indicated that he had mixed feelings . As Klass explained, the fact that nine other writers worked on his idea meant that the final product was not exactly the one he had intended. For instance, Klass said, "they took it out of small town America where I'd started it and moved it to a big city." More significant, he explained, was the portrayal of the boy in the film. To write about a child with cancer, Klass had "'spent a lot of time at a Los Angeles children's hospital, observing children in the cancer ward". When he describes te young cancer patients, he adamantly states, "They do not see themselves, and the doctors and nurses—the people who work with them don't see them as weak and pathetic. They're not. You've never met people who enjoy life so much and who are so optimistic. When they go into remission they really lead completely normal lives." He was determined that the young cancer patient who was a focal character in the movie would reflect the energy and optimism of the children whom he had met and watched. He adds, "So the last thing I wanted to do was present them or show them in any way as weak." Further, he notes that it is "impossible to be a good screenwriter without falling in love with your character and dreaming that your movie is going to go." When the nine writers who were chosen to revise his Desperate Measures script decided to portray the little boy as pale, weak, pathetic, Klass was troubled because his original intention had been altered. He was also troubled by critics' reactions. Klass said, "When the movie came out, the kid was pale and pitiful. A number of the reviews said, 'Klass should be ashamed of himself for doing this.' So that is one time when you just have to say, 'This is a really hard business.''' He admitted that being "scathingly criticized" for others' work is part of what makes Hollywood "a very rough business."

It was writing young adult literature that gave him a balance, and a sense of himself as a writer. That sense of being a writer sustained him during the years in Los Angeles when he was fairly broke and fully alone. And it led him to write his fine early books, Break Away Run (1987), also set in Japan and intended to convey what he had learned while living there; A Different Season (1987), which features a girl who joins a baseball team, and which was written in part as a response to a feminist friend with whom he liked to discuss gender roles; Wrestling with Honor (1988), a story that probes a son's attempts to connect to a father he'd lost to the Viet Nam war; California Blue (1994), an environmental and personal novel that centers on what happens between a boy and his father when the boy's discovery of a rare breed of butterfly threatens to shut down the factory in which his dad, who is dying of leukemia, works; and Danger Zone (1995), which was his own attempt, after the Los Angeles race riots, "to understand what life is like for people who struggle" to survive in racially explosive and dangerous sub-cultures of American cities. Klass says that he found, among writers and proponents of young adult literature whom he began to meet as his books became popular, "a WORLD" — a welcoming, friendly, positive place.

The Third Surprise

David Klass is calm about balancing his life, work, and location. He writes young adult novels and scripts for Hollywood primarily from New York City, where he shares a home with his wife, baby son, and the daughter whom the couple is currently expecting. He convinced me, throughout our conversation, that he is comfortable in all of his roles, and that he uses each productively as a weight to keep the others level.

I asked Klass to discuss the ways that screenwriting and writing novels for adolescents are similar or different, and whether or not the "dual" roles ever became "dueling" roles. His responses, peppered with specific examples, helped me understand how his work as a writer of young adult books adds a balance that allows him to continue to be productive in both arenas. And he helped me understand differences regarding the approaches and processes he takes as a writer, due to the different demands of the genres.

First, he explained that his writing in the film industry actually takes three different jobs. The most desirable job is that of the writer of an original screen play, which was his with Desperate Measures . A second job involves being hired by a studio to write an adaptation of a novel. This is the job that Klass assumed when he re-worked James Patterson's novel into the feature film, Kiss the Girls . The third kind of Hollywood writing involves rewriting scripts that a studio has bought from another author. It was this job that Klass was engaged in when he began the YA novel, You Don't Know Me . The story of how the characters and situations for that novel came to be is an intriguing detour:

Klass sounded almost apologetic when explaining the unusual way he began You Don't Know Me . He had been working for almost 18 months on a screenplay for Universal Studios. The script was a submarine suspense saga, and the director, John McTeirnen (director of Hunt for the Red October ), a stickler for details. Klass had an advisor at the Pentagon so that his work would be accurate and authentic, and he was doing his writing in New York City. One day during his tenure with the submarine film, while he was walking to lunch and at the intersection of Park and 57 th Street, Klass claims that he, "started to hear the voice of John clearly." He went home and wrote the first chapter almost automatically; the published version is virtually identical to that initial draft.

John's voice gradually "told [Klass] what his story would be." Even then, Klass admits, he was not sure what would happen with John. The author acknowledges that John took control of some of the scenes in the book. For example, Klass had planned to have John's first date with the coveted Glory Hallelujah turn out well; however, John refused to let the story unfold that way. The date was an utter disaster, ending with a humiliated and mortified John running away from Gloria's basement, in fear that Gloria's father was going to pummel him. Earlier in the date scene, Klass had John and Gloria attend a high school basketball game. When the author realized that he was giving too much careful attention to the ballgame itself, and not moving the narrative forward, he felt stalled, and had to put down the book. John stepped in to give him direction. When John took Gloria to the game, his irreverence toward Gloria's crowd sparked the eruption of a bleacher brawl. It was the fight, and John and Gloria's flight from it, that took the author's attention away from the details of the ballgame itself, and got him back on track with the novel.

This story illuminates other important differences that Klass finds when working as writer of young adult books and as a screenwriter. He states that for him, "novels are all about character," and insists that writers "have the battle won" when they create a character that they like, and that readers will like. In contrast, screenplays are "all about conflict and structure," and about "solving a puzzle" with the added challenge of compelling dialogue.

Although he confesses that being a writer in Hollywood is "a very tough business," he is quick to check what may sound like a broad stroke of criticism with this note: "I must say that I worked harder than I've ever worked in my life to break into that world. I feel really lucky," and adds, "When a Hollywood movie comes out, it's seen by everyone. You hear people talking about it on the street. It's seen by millions and millions of people." He realizes, on the other hand, that the impact of even the finest young adult books will have a much shorter reach. Nevertheless, he says that writing YA books that kids read is "a great joy." As a Hollywood screenwriter, he has learned to accept the fact that directors and producers lay claim to his work, and are free to change it to suit their needs, regardless of—or with no concern whatsoever for—his wishes. In contrast, he says that his editor will telephone him even if he is across the country if she has a question as minute as one concerning the placement of a comma. He explains, "The ability to completely control and portray a character without anyone tampering with it is a unique joy when compared to the world of film writing."

More Surprises to Come

Klass was happy to announce that he had just completed his newest young adult novel, Home of the Braves , which is scheduled for publication in the spring, 2002. In it, he returns to the serious tone that he is best known for, and avoids the temptation to try to imitate John's comic voice. Klass describes Home of the Braves as a novel that raises the question, "Why does an average American high school spin into violence?" He notes that the violence is not of the Columbine High School type, but more subtle— "bullying, gangs, town vs town rivalries" that crescendo into fighting, and so on. It is a book that we can look forward to, from an author who reminds us to take seriously the voices of teenagers, to attend to their concerns, to recognize their rights as citizens in our democratic society.

At the end of our conversation, Klass mentioned that he was a little nervous as he was preparing to go visit Scarsdale Middle School, where he would talk with 7 th graders about his experiences as a writer. I assured him that he was in for a treat, but was surprised that this hugely successful author would have any reservations about speaking to a group of readers—then realized that David Klass had surprised me yet again.

YA novels by David Klass (Each of these books will be ideal to introduce to middle or high school readers):

The Atami Dragons

(1984)

Breakaway Run

(1986)

A Different Season

(1988)

Wrestling with Honor

(1989)

California Blue

(1994)

Danger Zone

(1995)

Screen Test

(1997)

You Don't Know Me

(2001)

Home of the Braves

(2002)