ALAN v30n2 - Mentors and Monsters

Mentors and Monsters

Nancy Osa

I was never as brave as my characters turn out to be. In my fiction, the fearful boy can get back on his horse. The procrastinating mom can get a life. The shy girl can learn to ask questions. How on earth did I—the fearful, procrastinating, shy author—finally achieve what my characters were born to do?

How else? Through writing. And something more.

In 1994, looking for story ideas, I read a news report about the second annual "Friendshipment" — a humanitarian aid shipment to Cuba sponsored by the ecumenical group Pastors for Peace. Hurricane Andrew had recently hit, and the trade embargo largely prevented Americans from helping families in need. On the Friendshipment, volunteers physically collected medicine and other goods along a dozen caravan routes from Canada (giving the issue international significance) down to Laredo, Texas. There the cargo was escorted across the border into Mexico for shipment to Cuba, per U.S. regulation through a third country. The caravans gathered needed commodities for everyday Cubans, challenged U.S. travel and trade restrictions, and raised awareness of U.S.-Cuba relations in each of the cities and towns they passed through. (The Friendshipment has since become a semiannual event.) I wondered if any teenagers had participated, so I contacted my local Cuba group and found out that some had. This struck a chord. Here was my story.

I needed some context, so I pooled sources and began research. I knew next to nothing about the history of the Cuban nation or the relationship between our two governments. I had no idea what life was like on the island under the embargo. I was surprised, upon reading about the humanitarian effort, that people who were not of Cuban heritage were involved in a risky activity—collecting contraband with the intent to ship it to the island. In my ignorance, I was like most other Americans born after the 1959 Cuban Revolution. Except that I am Cuban American.

My father, Henry, came to this country from Cuba long before the revolution, as a replacement for U.S. doctors who were overseas during the Korean War. By the time I came along in 1961, sandwiched between the Bay of Pigs invasion and the Cuban missile crisis, Cuba had become a painful topic in our house. Growing up, I was the shy girl who learned not to ask questions. So, thirty-some years later, when I had to research Cuba for my new story, the whole reality of what had happened—what I had unwittingly lost—came crashing down around me.

19.9.94: I thought, What if things had been different? What if our government had negotiated with Castro? I could have grown up in two countries. I'd be able to speak Spanish. I'd know Mama [my grandmother] and my other Cuban relatives . . . things I'll never know. A life I'll never have. [from my journal]

For me, in those early days, Cuba was a wall print of palm-framed Morro Castle that hung in our dining room . . . the clacking of dominoes late at night after I was in bed . . . the heady aroma of my tía Emma's frijoles negros. Cuba was there —with us —not distant, far from my Chicago suburb in the palm of a dictator, and it existed then , not sometime in a past I had never known, and certainly not in any future. Other than the Morro Castle print, the only remnants of the past were the small framed photographs of my father's father, mother, and younger brother, who unlike his siblings had remained on the island. The pictures stood like sentinels on Dad's tall dresser, a shade truer than sepia tone, portraits of three people I had never met.

I realized in the course of my research that these were the people—at least, people like them—whom the Friendshipment, and other relief efforts, benefit. Perhaps some of my relatives had lived through 1993's Hurricane Andrew and needed things—from construction materials to everyday items like soap. Yes, I was slow to make the connection. And it was connection I wanted. Suddenly it all became too personal for me to blanket in fiction. I had to reach in another direction.

Of the three portraits on the dresser, only Eduardo, Dad's brother, was still living. The two hadn't spoken in twenty years. But my uncle had recently made contact with his sisters, my aunts who live in Florida. I learned that Eddy was married and had a young son and daughter. I got out my high school Spanish textbook and wrote them a letter.

Septiembre 1994:

Querida Familia, Quiero que Uds. me conozcan; soy Nancy, la hija de Enrique. Que me les presente a Uds: Vivo en la costa Pacifico de los E. U., en una pequena ciudad, Portland, Oregon. Tengo 33 anos, yo soy una escritora de libros y cuentos para muchachos. [from my September 1994 typed letter]

I began, literally, "I want that you know me; I am Nancy, daughter of Enrique." And I told them a bit about my life. We struck up a correspondence, and I got to know my closest relatives in Cuba.

Now I had a real reason to write my story. I hitched a ride partway on the Friendshipment caravan the following spring and used what I learned to create my character, thirteen-year-old Cuban American Violet Paz. I felt comfortable writing from my experience and excited about the timeliness of the story. Americans had begun to "notice" Cuba again: The Soviet Union had fallen. Cigars were back in vogue. Grassroots activism was on the rise. And, in my own bit of synchronicity, wonder of wonders, my dad had picked up the telephone and called his little brother in Cuba. Inspiration? I was drowning in it. I crafted a short story for middle-grade readers that I planned to develop into a novel and began sending it out to publishers. Reviews were mixed. Most editors were put off by the political bent of the piece.

About this time, I received a letter from author Virginia Euwer Wolff, to whom I had sent fan mail. I'd heard that if you wrote to a children's author, you'd likely get a reply, so, pure of heart, I told Virginia how much I liked her book Make Lemonade. She lives nearby and asked me out for pizza and to talk about the writing life. I went—no motive—a bundle of nerves and shy about presenting myself as an author. When I explained my situation —starving artist, scraping for stamps for SASEs. . .hell, I'd taken the bus to get to the restaurant —Virginia reinterpreted it for me: I had made sacrifices for my art. Instantly, I was lifted above the cramped rental house, archaic computer, and lack of wheels to a place where my work was what mattered. Virginia waved her wand again, and I had contacts:

21.9.95: I met Virginia Euwer Wolff at the Heathman Pub on Thurs. for pizza. I had a great time. She said I should know more writers around here and gave me some names. Her editor is moving . . . but she gave me the name of the multicultural editor there, "because you didn't ask." [from my journal]

Sometimes it's good not to ask questions!

Before I could act on that good fortune, I received word from another publisher that my short story had been accepted for an anthology by Hispanic authors, to be edited by Alma Flor Ada and Isabel Campoy. Alma Flor would be in my town soon for a conference and wanted to meet me. I had read My Name is María Isabel and was excited to hear from her.

Again I gathered my courage, begged a ride to the suburbs, and met a famous author in a public place. We connected immediately; Alma Flor was born in Cuba and was outspoken against the embargo. We talked for a very long time over dinner about writing and living with split families and dealing with Cuban parents. All of a sudden I felt . . . normal. Crazy, but normal—I could face these problems as other people did. And doing so would enrich my work. "So get to the keyboard," Alma Flor told me. "Maybe something about what it's like to have green eyes and be Cuban."

I drew from our meeting the theme that was then emerging in children's literature: that the expression of my cultural experience, however diluted or incongruous that experience may be, is a valid representation of the truth. Of how my world, and that of others in the same boat, works. And I began to see my half-Cubanness—and my Spanglish-speaking, bad-domino-playing, can't-dance-the-mambo self—as worthy of a story.

Over the next couple of years, I worked at drawing the short story out into a novel, but had difficulty distancing my writing self from my political self. The subject was too freshly painful to me. So I began another novel with Violet Paz as my main character. And this time, I was determined to find something to laugh about.

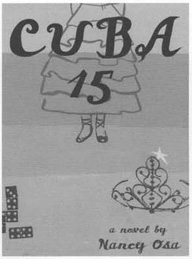

Knowing that my own diluted cultural experience was authentic in and of itself gave me new courage. I began to plot a story that grew from my roots and put out new shoots. The novel, which would become Cuba 15 (Delacorte Press 2003), focuses on Violet's quinceañero , or Cuban coming-of-age ceremony. The traditional event forces Violet to reevaluate her relationship with her heritage and with her Cuban-born father, Alberto, which she does with honesty and humor. I myself had never been to a "quince," and I'd never asked those pesky important questions about my father's Cuban past when I was growing up. But I could imagine someone else doing those things. So I wrote.

When I finished revising my drafts of Cuba 15, I was sure this was the book I'd meant to write. Winning the 19th Delacorte Press Prize sealed the deal . . . until my Random House editor, Françoise Bui, requested revisions.

You've written a funny and touching story that offers a delicious slice of Cuban culture. And that's precisely what 1'd like you to expand on. Your own synopsis . . . states that . . . "the rift between the United States and Cuba has caused a culture gap in the Chicago-based Paz family, as well as 'gaps' in how the Pazes relate to one another and to their family on the island." Yet this collision and gap seem largely glossed over. They are the missing layers of the story—ones that are crucial to incorporate if you want your novel to resonate with depth and texture. [from F. Bui's February 15,2002, letter]

Why some people don't enjoy criticism is beyond me—I was touched by these insights gained from such a thoughtful read, and fired with pride. I could go deeper.

But deeper is difficult, even painful. I worked hard on the manuscript . . . but again I glossed over the crux of Violet's dilemma, her parents' lack of trust that prevents Violet from coming to grips with her Cuban roots. Françoise was not fooled.

You've done a great deal to embellish the rift between the Paz family vis-a-vis their views on Cuba. But, as I said in my first letter, I feel that a big emotional pull—an incident that jolts Alberto into a fury over Violet's growing interest in Cuba—is missing. You need a climax. [from F. Bui's July 2, 2002, letter]

The gentle suggestions in her revision letter tugged at the corners of my mind until it opened a bit. Then a bit more. Françoise was telling me that "deeper" was not enough— wider was more like it. Still I mentally argued with her: But that confrontation would never have happened in my family! And the question hit me: But what if it did? Imagining my way into someone else's life wasn't real enough. I needed to see through their eyes.

So I finished the book. Writing from beyond my experience allowed me to fully incorporate that climactic bit of fiction as a truth in my life. Through Violet's humor and bravery, I find that I am somehow enhanced. We help each other, as Violet jokingly puts it in reference to her friend Leda, "like those relationships where one fish scrapes dead barnacles off the other." (Cuba 15)

It's hard to write alone. Scary, even. And deciding to confront a difficult subject is often not enough. In my case, mentors helped me complete the equation. Perhaps all authors need "personal trainers" to beckon us through the dark undergrowth of our psyches, to let us come out the other side braver for having examined our fears. What a gift when one happens along! I've discovered that mentors are where you find them; sometimes neither you nor they know that they are mentors until much later, if ever. They are like good sorcerers casting generous spells. They help us spin our fears and demons into gold. My gratitude knows no bounds.

The 1994 anthology project was eventually discontinued by the publisher. But, often, that rainy night in October when I first met Alma Flor floats back to me in all its promise, reminding me of the many wonderful, selfless people who have helped show me the way so that I may do the same for my readers and other writers. It's a rare occupation that pays off for everyone, and I know how lucky I am. In my journal the following day, I wrote, "Alma Flor hugged me before she said good night. Is this a great job or what?"

Nancy Osa is an author, editorial consultant, and all-around

fun gal based in Portland, Oregon.

Visit her at www.nancyosa.com.

Cuba 15,

by Nancy Osa

Delacorte Press Publication date: June,2003 (ISBN: 0-385-90086-4)

Brava, Nancy Osa, author of Cuba 15, and recipient of 19 th Annual Delacorte Pres Prize for first novels. I can hardly wait to get this positive, artistic book into the hands of every teacher and middle and high school student that I know. It is a true treat to introduce you to this novel and its author Nancy Osa, a wonderful new voice in YA literature.

In Cuba 15 , we get to know the multi-dimensioned Violet (Violeta) Paz, exactly at the time in her life when her grandmother (Abuela) is insisting that she have a "quinceanero"—a party to celebrate her fifteenth birthday that. In Abuela's Cuban tradition, the quinceanero marks the time that females step into womanhood—a Cuban debutante, if you will. Violet, whose energy and wacky sense of humor are suspiciously similar to Osa's herself, wants nothing to do with what she fears will be a disaster—after all, she hasn't worn a dress since the 4 th grade, she doesn't have enough friends to fill the auditorium where the event is to be held, and she worries that the cost is too much for her family. Eventually, though, as Violet learns more about the tradition of the "quince," she begins to understand, and respect, why it means so much to her Cuban grandmother that she participate in it. As the story's main plot unfolds, several entertaining side shows also occur: we see Violet's "loco family" set aside an entire weekend for a dominos fest, and giving the game the kind of passion that many of us attach only to cheering for college football games or spotting Hollywood celebrities. We are charmed by the Spanglish speaking-Abuelo and Abuela, as well as by the eccentric Tia Luci, a cigar-smoking cousin, and the wise and wily Senora Flora, "party planner for the stars". We are pleased to see that Violet becomes a successful member of the school's speech team, and delighted that, unlike many of the adolescents we meet in YA books, she enjoys her family, and is eager to spend time even with her younger brother. We laugh with Violet when her mother suggests new names for her latest scheme: a drive-through bakery called Catch 'Er in the Rye. We applaud Violet for creating, from the traditional quinceanero, a celebration that makes her proud of herself and her family. And we are also reminded of serious political and cultural connections and disconnections between the US and Cuba — at a time when changes in those relationships are imminent.

Nancy Osa offers readers engaging dialogue among endearing characters within the context of an aspect of our American culture with which many of us are unfamiliar. This book will be an extraordinary collection to classroom libraries, and one that English/language arts teachers will want to share with their friends across the curriculum.

Now—anyone have a pocketful of dimes? I am ready for a long game of dominos!

A handful of quotes from Cuba 15:

" 'The quinceanero, m'ijo, this is the time when the girl becomes the woman.' "

" 'I'd never even heard about this quince thing before Abuela brought it up. I don't know any more than you do, other than what I've read in this book.' I patted the copy of Quinceanero for the Gringo Dummy on my desk."

"In between siestas that afternoon, I lost my shirt to my grandmother. .. 'La siento, Violeta, pero I win again!' she sang cheerfully from pimiento-colored lips, reaching for the pot as the other players commiserated with me, one game after another. Still, I kept coming back for more."

" 'Dad's face scares me when he talks about Cuba.' "

" 'My job, Violet, is to take what is true about Violet Paz and put it into the fiesta. The quinceanero is a statement about who you are and where you are going.' "