ALAN v35n3 - Of Poetry and Post-it Notes: Ringside with Jen Bryant

Of Poetry and Post-it Notes:

Ringside

with Jen Bryant

An Interview

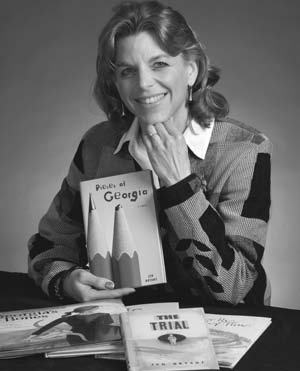

Before poet Jen Bryant published her first YA novel, she had already written a number of successful picture books and biographies for young readers. Building on her talent and experience, Ringside, 1925 is her third novel in poems for young adults (see review, p. 20. Her previous books also include The Trial (2004), the story of the trial of Bruno Hauptmann who was convicted of kidnapping the Lindbergh baby, and Pieces of Georgia , the story of thirteen year old Georgia who is developing her artistic talent. In her recently published, Ringside, 1925 , Jen returns to historical fiction to tell the story of the Scopes “Monkey” trial to test the legality of the Butler Act of Tennessee designed to prohibit the teaching of evolution. Using nine narrative voices, she captures the drama, the hype, and the irony of the trial that pitted science against religion.

Her poet’s sensibilities contribute to the creation of believable characters, vibrant settings, and compelling plots. An additional feature is the meticulous research that is a significant element of all of her novels. Readers can expect to be transported to the locale and the period she writes about. After reading The Trial , a student said: “She even makes history interesting!” If she can do that for a disinterested student, imagine the benefits of using her books in your classes.

Jen Bryant

This interview was conducted primarily through email, but also based on conversations with Jen Bryant at Random House dinners at NCTE in Pittsburgh in 2005, Nashville in 2006, and New York City in 2007. You can learn more about Jen Bryant and her work by visiting her website at www.jenbryant.com.

Conversation with Jen Bryant

TAR: Prior to writing The Trial , you were a poet who had also published picture books and biographies for young readers.

JB: The Trial evolved from a collision of ideas and personal experience. Because I grew up in the town of Flemington, NJ, where the Lindbergh trial took place, I was privy to the actual setting and to its oral history as told to me by my family members. My grandmother and her sister, for instance, remembered running up to the courthouse after school let out to try and catch a glimpse of the Lindberghs, or of one of the many celebrities who attended the trial in January, 1935. Hearing their childhood stories also made me realize how difficult the Depression Era was for most families— and what an incredible experience it was for their little town to host such a world-wide media event.

Thirty-five years later, my own journey to and from school each day took me past the Flemington Courthouse, which also served as the county jail. On my way home, I would frequently look up into the jailhouse windows and see what I thought were the inmates moving around inside. It wasn’t difficult, then, to imagine myself back in 1935 when one of the shadows might have been Bruno Richard Hauptmann, the man accused of the baby’s kidnapping and murder.

say that my books are

well-planned in advance

...but such is almost

never the case; I seem to

need to back into them

somehow-or come at

them sideways from

another project or even

another genre!

Although I carried these memories with me into adulthood, it wasn’t until my late thirties that I began writing a few poems (intending to send them to literary magazines) based on the kidnapping events. As I was playing around with these Lindbergh-case poems, I was also reading some books on the Lindbergh family, watching movies from this time period, and going back to Flemington for family visits. It occurred to me that I’d never read any novels for young adults about the investigation or the trial, so I thought—why not try and write more poems and see if they don’t turn into something that looks like a novel? (I would love to be able to say that my books are well-planned in advance . . . but such is almost never the case; I seem to need to back into them somehow— or come at them sideways from another project or even another genre!)

TAR: What or who influenced you to write novels for young adults?

JB: Jerry and Eileen Spinelli, who have been incredibly wonderful friends and mentors, both read the manuscript and gave it a thumbs-up. Jerry put me in touch with Joan Slattery at Knopf and I’ve been working with her ever since. The TRIAL is dedicated to Jerry and Eileen, and to my friend and poet David Keplinger, who taught me much of what I know about writing free verse.

TAR: Did your experience in writing biographies help you make the transition to writing novels? What challenges did you find in writing for a young adult audience?

JB: I love to research—which is why, I think, I continue to write historical fiction and biographical picture books. (The poet Robert Pinsky said that real events are frequently more unbelievable than anything you could make up. I couldn’t agree more.) My contemporary novel, Pieces of Georgia , also includes a lot of art history as well as stories about the three generations of Wyeth painters. So, yes, I do believe that writing biographies helped to prepare me for novels, especially for weaving fictional plots and characters with real/historical events and individuals. When I start, it’s like a big puzzle that looks almost impossible to put together (hence my tendency to back into a book, I guess!) But gradually, as I move along, the story seems to require certain details and information but not others. I gather so much more information than I ever use . . . but I also believe it helps to make the story richer in the long run.

One of my biggest challenges in writing this kind of book for young adults is finding ways to include enough of the necessary information about what actually occurred but still maintain the story’s natural tension. The key, I think, is to create fictional teens who have their own compelling voices and let them tell me what to leave in and what to leave out.

TAR: Since all three of your novels are written in verse, do you consider yourself a poet who writes novels or a novelist who uses verse? Are all of your drafts in verse? As a poet, would you find it more difficult to write a novel in prose than in verse?

JB: I’ve been trying to figure that out myself! I don’t really know. I suppose I just write stories in a way that pays particular attention to rhythm, imagery and sound. Not because I set out to write them this way; it just seems to be the more natural form for me. I can’t be sure, but it may have something to do with the fact that I majored in French and minored in German and taught both for a number of years after I graduated (from Gettysburg College.) So I guess I’ve always been interested in—and attracted to—the rhythm and sounds of language, as much as by “what happens.” My favorite prose writers tend to be folks who are very lyrical—Annie Dillard, for example, was one of my early favorites. When I teach children’s literature, I use Gary Soto‘s poetry and short stories together to show how language can be used beautifully—and to give the reader that vicarious “you are there” feeling. He’s great. I keep his Collected Poems on my nightstand.

So far, all of my novel drafts have been in verse. But I want to try and write a novel in more traditional prose; it’ll just have to feel right, I guess.

TAR: Why did you choose to write about the Scopes trial in Ringside 1925 ? Are you surprised that the teaching of evolution continues to be under such fire? Do you think the latest reaffirmation from the scientific community that creationism or “intelligent design” has no place in the science curriculum will have any impact on the attention the book receives?

JB: Again, it seemed that a number of things fell together over time to lead me there. I ran across a lot of great sources for famous trials while I was researching the Lindbergh case and of course, the 1925 Scopes “monkey” trial was among them. My father-in-law loves the movie “Inherit the Wind,” and we would watch it from time to time whenever the family got together. Then there was all that press coverage of school districts being challenged about their science curriculum and how they were being pressured to include creationism in it. It just seemed, at some point, that I couldn’t NOT write it, especially since I had already fictionalized a historical trial.

Western way of thinking

seems to exclude the

possibility of allowing two

very different kinds of

truth to co-exist...

rather, we seem to insist

on an "either/or"

approach, much to our

detriment, I think.

As for being surprised—I’ve reached an age where many things still awe me, but very few things (regarding human nature, that is) really surprise me. In the U.S., our particular Western way of thinking seems to exclude the possibility of allowing two very different kinds of truths to coexist . . . rather, we seem to insist on an “either/or” approach, much to our detriment, I think. A lot of it is ego-driven; the need to be “right” slams the door closed so early on other possibilities, other ways of viewing our existence that allows for a wider, deeper view. Studying foreign cultures and languages made me realize that addressing our spirituality, no matter what conclusions that brings, is part of the human condition. Moving forward in our scientific knowledge is also part of human nature. The reality is that so many of our current scientific breakthroughs—including our best cancer drugs, antibiotics, etc.—are based in part on the theory of natural selection. To throw that out would mean going back to the Stone Age in many ways.

That being said, in writing Ringside, 1925 , I tried to focus on the historical trial as much as possible, and not on the current school vs. church squabbles. I attempted to create characters who would react in different ways to these carefully watched proceedings and draw their own conclusions.

TAR: I remember learning about both the Lindbergh baby and Scopes trials from my parents who remembered the trials from their youth. What impressed me was their point that these trials, ancient history to me as a child, had changed the social fabric of this country. What do you see as the legacies of these trials?

JB: These two cases were similar in some aspects, but very different in others. Both took place in small, semi-rural towns during the first half of the 20th century, attracted widespread national press coverage, and remain landmark cases of our American judicial system. But even though John T. Scopes was the defendant, the Tennessee trial was really one of ideas (one of the most fun scenes in the books to write was where Scopes goes missing and no one really notices.) The Scopes trial was almost like a nationwide caucus because it gave everyone permission to examine their own views on evolution and whether it was or was not compatible with the Biblical creation story. So when you read the thoughts and conversations of the Dayton citizens in Ringside , the same sort of thinking and dialogue was happening across the country because of the case. And we know that continues even today, in homes, schools, churches, and in the media.

The Lindbergh case, on the other hand, accused a German immigrant handyman, Bruno Richard Hauptmann, of the kidnapping and murder of Charles Lindbergh’s baby son. Hauptmann was very visible in the courtroom and it was his life that was at stake. I can hardly begin to describe here the number of social and economic factors that affected the outcome of this trial (I often suggest the movie Seabiscuit , to give students a context for the Great Depression); even now, it still fascinates me. But suffice to say that in 1935, our country was in the depths of the Great Depression, Hitler was on the rise in Germany, radio was at its peak and television was being born, mass communication became faster and more reliable than ever, and the concept of “celebrity” became crystallized. Americans worshipped Lindbergh like a god (an aspect of his life he detested), suspected anyone recently arrived from Germany, and became desperate for distractions from their poverty and despair.

modern kids because it

has the same aspects of

celebrity worship, ethnic

profiling, and media

exploitation that we

encounter today.

This trial resonates with modern kids because it has the same aspects of celebrity worship, ethnic profiling, and media exploitation that we encounter today. I’ve visited schools where they’ve spent the better part of the year debating and dissecting the trial, trying to determine if justice was served. The kids (and teachers) also realize how far forensic science has come and how few tools were available to crime solvers back then. The recent debates over capital punishment and the government’s treatment of Iraqi war prisoners make cases like this seem timeless.

TAR: Over the years, a question my students frequently ask authors is about their process of writing. Could you share with us the process of the “making of Ringside, 1925 ” as an example of how you work? What made you choose this event? I know you visited Dayton, Tennessee, and attended a reenactment of the Scopes trial; what other types of research did you do? How long was the research process? In writing historical fiction, do you complete the research before you begin to create characters and frame their involvement in the historical events?

JB: Actually, I did a lot of reading about the Scopes trial even before I decided to write a novel about it. That reading included the wonderful Pulitzer Prize winner Summer for the Gods , plus about seven or eight other non-fiction books and probably twice as many magazine and website articles about Darwin, Creationism, the trial, the attorneys, and the ongoing controversies about school curricula. There was just so much there; I realized how pivotal this trial was in terms of opening up the conversation about science and faith and how conflicted many people felt about these areas. So—the natural tension and intrigue were already available; I just had to figure out a way to present different perspectives on the arguments so that the reader would be left to decide where he/she fell on the continuum of these issues. Originally, there were eleven narrators, but I cut that back to nine, making sure I used—within the constraints of that particular town and the historical era—a variety of ages, genders, educational backgrounds, ethic groups, and so on.

I enjoyed “speaking” in the voices of these various characters much more than I thought I would. The challenge was to keep building their personalities and their inter-relationships while still moving forward with the actual events of the trial. Plus, as the story grew, I had to keep good track of who had spoken when and be sure not to let too many pages pass without hearing from a character. Those brightly colored sticky notes became an asset in the final months. And so did my husband’s pool table!—I would lay out the book section by section so I could see clearly who had spoken, how often, and what part of the story they had furthered. Several times, I just felt perfectly incapable of keeping all of the plot points and characters straight in my mind. But, several dozen packs of sticky notes later, it did work out.

I did go to Dayton, Tennessee, and saw the reenactment (twice) in the original courthouse. I poked around town, talked to some of the current residents, bought a few souvenirs, and generally tried to imagine what it was like there in 1925. The town itself is still very quiet. As with many older towns, once McDonald’s, mini-malls and Wal-Marts come in, the boroughs empty out quite a bit. This seemed to be the case for Dayton as well, though it didn’t diminish the charm at all. The folks there have quite a lot of civic pride. And the exhibits and memorabilia in the Scopes Evolution Museum below the courthouse were hugely helpful.

TAR: How long did it take to write the novel? How many drafts of the novel did you write? Do you write every day? How many hours a day do you work?

JB: I never keep track of how long something takes me to write because I feel the process is a lot more circular than linear. If I had to say, though, I imagine the actual writing took almost a year. And then, of course, there are revisions, so I guess that’s about another month or two of days at the desk. The draft question is hard, because I’m always saving various bits and pieces of scenes and scraps of things . . . so my “draft” isn’t what most folks probably think of when they use that term. I tend to write novels section by section, so I couldn’t even begin to guess! (Lots . . .) I try to write—and by that I mean work on the next manuscript that’s due—for three to four hours each day, six days a week. Of course as other books come out, I’m also doing events, promotions and school visits, so it’s difficult to strike a good balance sometimes. When I feel like I really need to finish a project, I return to my college in Gettysburg, PA, where I hunker down in a dorm or hotel room for several days and just write. There’s something about staring out the window at a long row of cannons that produces a sense of urgency; it always works.

TAR: Characterization is a crucial key to the success of any YA novel. When you are writing in verse you have an interesting constraint by form. For instance, any back-story, direct description or conversations by or about the character must be stylistically consistent. How do you achieve this? What do you do to build a character? How was this different in Ringside than in your first two novels?

come from? I suspect they

are a mish-mosh of voices

I've heard throughout my

life time...a marriage of

quirks and habits, of

physical and emotional

traits that I've observed in

others-and in myself too.

JB: Great questions . . . hmmm. The truth is, after I am saturated (though far from finished) with my reading and other research, I just start writing in a voice I think might be in that place or time. If it works, I stick with it; if it flops, I try another one. Very unscientific, I know. But I think this part of the process must be a little bit of a mystery to me, too. Where DO those voices come from? I suspect they are a mish-mosh of voices I’ve heard throughout my life time . . . a marriage of quirks and habits, of physical and emotional traits that I’ve observed in others—and in myself too. In Pieces of Georgia and in The Trial , I felt like there was a part of me that got into those two protagonists—and yet there were certainly aspects of those girls that came from somewhere else. I’m not sure how it works, but the language itself often leads me to the characters. The more words I can get on to the page, the clearer the character becomes. And—with me at least—I do think that characters emerge from their very particular settings and that their time and place is integral to who they are.

Ringside, 1925: Views from the Scopes Trial

by Jen Bryant

Reviewed by Jean E. Brown

[Alfred A. Knopf Books for Young Readers, 2008, ISBN 978-0-375-84047-0]

Long before our court system was dotted with cases of celebrity bad behavior, the media cut their teeth on another highly visible court case, the Scopes trial in 1925. The trial was designed to challenge the Butler Act of Tennessee that banned the “teaching of any theory that denies the story/ of the Divine Creation of man/ as taught in the Bible.”(p.12). In her latest novel, Jen Bryant transports us to rural Dayton, Tennessee, where the Scopes trial propelled a scientific/religious difference of opinion into a political/philosophical chasm between the believers of evolution and the believers of creationism that still remains unbridged eighty-three years later. In this novel-in-poems, Bryant captures the essence and the irony of the trial that was more circus than substance when the judge refused to allow crucial testimony for the defense.

In a plan hatched in Robinson’s Drug Store, the town leaders persuaded John Scopes, a high school science teacher, to agree to be arrested for teaching Darwin’s theory of evolution. His arrest means that the town could challenge the Butler Act. The American Civil Liberties Union wanted to challenge the Act and agreed to have the most famous and successful trial lawyer of the time, Clarence Darrow, defend Scopes. The prosecution counters with Darrow’s friend and former Presidential candidate, William Jennings Bryan, a famous minister and orator.

The trial brought the town national attention as well as an influx of people including famous lawyers, scientists, visitors, newspaper reporters, and a needed infusion of cash. By using multiple narrators, Jen Bryant successfully captures the spectrum of ideas, beliefs, and emotions that the trial evoked. More significantly, the trial drew battle lines between knowledge and faith that sparked the still-raging debate.

The nine clear and distinct narrative voices effectively capture the circumstances, the setting, the impact, and the irony of the infamous “Monkey Trial.” The narrators include three high school students: Peter Sykes, a budding scientist with a passion for geology, and his best friend Jimmy Lee Davis, who follows his mother’s strict adherences to the Bible. The third high school student is Marybeth Dodd, who is bright and independent and who recognizes that John Scopes “trusts us to learn both (science and religion)/ and know the difference” (p. 13). The fourth youthful narrator is 12 year-old Willie Amos, who helps his father with odd jobs in their segregated community and dreams of breaking racial barriers to become a lawyer. Additionally, we hear the voices of townspeople: Tillie Stackhouse, who is reading Darwin and runs the local boarding house where many of the people who came to Dayton for the trial stayed; Constable Fraybel, who keeps order and wryly reflects the irony of the trial; and Betty Barker, a Christian fundamentalist who believes that anyone who disagrees with her is the pawn of the devil. The Dayton residents reflect the continuum of beliefs and reactions as Bryant skillfully presents the complex issues of the evolution versus creationism debate, both the intellectual and the emotional.

The final two voices are of outsiders: Ernest McManus, a Methodist minister, who traveled to Dayton to watch the trial; and Paul LeBrun, a reporter from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch . These two characters serve to report on the trial. LeBrun reports though his news accounts while McManus presents a balanced view between science and religion.

Jen Bryant sets the stage for players to react to the trial and show its impact on the community and the nation beyond in the novel. The multiple narrators describe the compelling events during the trial, but they also reflect the attitudes and inter-relationships within the community. As the buzz about the trial increases, tensions rise, friendships are strained, and family members disagree. Pete and Jimmy Lee find themselves at odds over the issue as do Marybeth and her father. But the trial also opens Dayton to the world that suddenly allows Marybeth, Willy, and Pete to dare to dream of possible new futures with greater opportunities than they had ever hoped.

At the same time, interest in the trial creates a circus-like atmosphere in the town. Reporters from around the country, including a radio crew from WGN in Chicago, arrived to broadcast from the courthouse; religious leaders, scientific experts, and tourists flocked to the town. While the duration of the trial itself was short, it did put Dayton on the tongues of the nation and money in local hands.

Jen Bryant not only captivates her readers with her storytelling abilities, but she also creates a vivid sense of the times by providing us with numerous cultural allusions. With references from George Gershwin to jazz; from Babe Ruth to Gertrude Ederle; and from bootleg whiskey to the Ku Klux Klan, Bryant successfully places the Scopes Trial in a broad social context of the 1920s, a time of change and controversy.

Perhaps one of the most intriguing parts of the book for today’s media-savvy young adult readers is the contrast of today’s tidal wave of media events with the circus-like atmosphere created by the trial. The trial was a national media event with the amount of press and radio coverage and the number of visitors to the tiny rural community. The media coverage of the Scopes trial was an initial step to the ever-building crescendo that is the media frenzy that exists today. This media effect, also explored in Jen Bryant’s first novel, The Trial , the story of the Lindbergh Trial that took place ten years after the Scopes trial, provides readers of both these books with insights into the times.

Ringside, 1925 , as with all good historical fiction, makes the time and events of the book easily accessible to young adult readers and bridges the years by presenting issues that remain relevant today. The debate between the scientific community that supports the teaching of evolution and the fundamentalist proponents of what has now come to be called, somewhat euphemistically, “intelligent design,” continues today. The reactions and emotions that the various narrators express resonate with today’s readers. Because of its insightful exploration of the issues, the book is an excellent addition to any classroom and has broad cross-curricular implications.

TAR: Why did you decide to use nine very different narrators in Ringside ? What did you find to be the unique challenges of using multiple narrators? What techniques did you use to establish and maintain the unique character of each? When you have nine narrative voices how do you find a balance?

JB: Unlike Pieces of Georgia and The Trial , which have a single female narrator, Ringside uses multiple speakers to tell the story. The subject matter seemed to require it. The modern resonance of that trial and the continuing controversy about the issues suggested to me that my readers would necessarily fall along a wide spectrum of feelings and thoughts and beliefs . . . so why not represent that spectrum? For each of the narrators, I did do a brief character sketch—but when I look back, I deviated from my original notes in several cases, because the language/voices themselves led me elsewhere (when they invent a GPS for novelists, I’ll be the first one in line!) But I realized that I would need to distinguish one speaker from another—not only in the way they spoke and how fervently they agreed or disagreed with the idea of evolution—but also in how their “voice” appeared on the page. For a poet, this is just plain FUN. . . Peter spoke in tercets, Jimmy Lee spoke in long, skinny, continuous stanzas, Willy and Marybeth spoke in free verse, Betty Barker spoke in pretty strict meter and rhyme, and Paul Lebrun often gave us his actual (prose) newspaper articles. So, yes, you’re right . . . it was challenging to switch back and forth, but it also flexed a lot of poetry muscles for me.

As I mentioned already, I struggled frequently to strike a balance between the factual information of the trial and developing the back story and interrelationships between the fictional characters. In addition, I had to balance the speaking parts themselves, making sure they were somewhat evenly distributed, and deciding who should impart some of the most important details of what actually happened in the courtroom. Those sticky notes, and my wonderful editors at Knopf, helped to steer my course when the story grew too unwieldy. I’d still be leaning over that pool table if it weren’t for them!

TAR: In the Author’s Note for your first novel, The Trial , you speak of growing up in Flemington. The specter of the Lindbergh trial must still permeate the community even now seventy-three years after Hauptmann was sentenced. You also say that the trial has “fascinated—and haunted” you. Did you feel compelled to write this book? How did writing it affect you personally?

JB: You’re right—the Lindbergh trial does still permeate the collective psyche of Flemington, especially those who have lived there for several generations. As you can tell from my answer to your first question here, it also permeated mine! I recall being afraid, at one point in my childhood, that someone would come through my window and snatch me away. That fear—I’m sure—came right from hearing people around me recall the Lindbergh baby kidnapping and details of the baby’s room and the home-made ladder leaning against the side of the house.

Now when I visit schools, the kids are just as riveted by the details of that crime. Perhaps because it’s so basic and so conceivable . . . and yet forensics being what they were in 1932, it’s still a mystery to be solved. They really get into debating the evidence and the witnesses’ testimonies. It’s great fun, so that’s the fascination part of it—depending on how you “read” the clues, the testimonies, and the evidence, and then take into account the national economic and world political situations—you can reach very different conclusions. That natural intrigue was one of the things that compelled me to write the book— that and my deep familiarity with the physical landscape of the town, which I knew I could make use of in the story.

affected me most while

writing this was how

difficult it must have been

for the Lindberghs, espe-

cially Anne, who must

have had to handle an

awful lot on her own in

the wake of the kidnap-

ping and murder.

Even though it’s clear that the accused man did not get a fair trial, we can’t forget that this was an incredible personal tragedy. One of the things that affected me most while writing this was how difficult it must have been for the Lindberghs, especially Anne, who must have had to handle an awful lot on her own in the wake of the kidnapping and murder. Even though there’s not a lot about her specifically in my novel, I developed a real appreciation for her spirit and resilience. Charles Lindbergh could not have been an easy guy to live with and yet somehow she persevered, after losing her first born, to have five more children, fly around the world, write many wonderful books, and maintain a marriage (despite her husband’s loose definition of that term.)

TAR: Pieces of Georgia is the only one of your novels set in contemporary times. How was writing it different from your historical fiction?

JB: This is another book I felt compelled to write, though I’m not absolutely sure why. The protagonist is a 13-year old girl who wants to be an artist, but has no money for lessons and no support from her father. I think part if it was that I wasn’t a writer until my thirties and I wasn’t formally schooled in writing, either. I just had to figure a lot of stuff out on my own and look for good models, which is exactly what Georgia does with her drawing. So—from an emotional standpoint at least, it was somewhat autobiographical.

The book also allowed me to pay homage to the Wyeth family of artists, from which, I believe, in some mysterious way, I have also drawn inspiration. I’ve read a lot about NC Wyeth and how he worked and raised a family (good material for all working parents) and also about Andrew and how he struggled to become his own kind of artist, while still honoring his father. Then there’s Jamie Wyeth—whose work is totally different but equally deep and wonderful. His portraits are described in POG , and his “Portrait of Pig” plays a fairly important role in the story.

And so does the Brandywine River Museum itself. When I was teaching more often at West Chester University, I would take my students there (usually kicking and screaming until they saw the place—then they didn’t want to leave!) and give them a number of things they could write about relating to the museum’s collections and the three generations of Wyeths. I would accompany them as they toured the galleries and made their notes and it was during one of those times that I began to toy with the idea of setting a YA novel there . . . or at least partly there. Setting is so important to me. I do believe people are products of their settings and the right setting for me seems to generate characters. So that aspect is the same as in historical fiction.

My challenge, really, was to get the characters away from all the technology that comes between people these days—the cell phones, the computer networking programs, the Blackberries. Part of that was solved by putting Georgia on a horse farm where much of the activity is still close to the land and also making her much less affluent than her neighbors and many of her schoolmates. The irony is, of course, that she is richer for having developed an inner life and a true, self-directed passion for something, while the over-scheduled suburban kids are just blindly bouncing from one extra curricular activity to another, trying to stay afloat.

TAR: How does teaching children’s literature have an impact on your writing and does your writing have an impact on your teaching?

JB: Well, the biggest impact has been time: the more I write, the less I teach and visa versa. I suppose because I’m pretty intense when I’m working, I have a hard time doing both well. So—now I just teach in the summer, which seems to work well and I don’t write anything at all then.

I do love having long class discussions about good children’s literature, as well as introducing my students to books written by our local writing community. We read and discuss books by Jerry & Eileen Spinelli, Lloyd Alexander, David Weisner, Donna Jo Napoli, Laurie Halse Anderson (now lives in NY), Lindsay Barrett George, Judith Schachner, and Charles Santore, among others. I also spend quite a bit of time on poetry—most of that getting them NOT to be afraid of it—helping them develop a vocabulary for talking about it and also a repertoire of poets whom they enjoy.

TAR: Your picture book about William Carlos Williams is due out later this year, so what are you working on now?

JB: Yes, it’s called A River of Words (Eerdmans, August, 2008) and it’s just off to the printer’s today. We’re very excited about it. Melissa Sweet did some amazing mixed-media illustrations for that and really threw herself into researching Paterson and Rutherford, New Jersey, in the early 20th century. I have never met the illustrators for my previous three picture books, so I’m excited that Melissa and I will both be at IRA this year.

For Knopf, I have a sixties-era novel in to my editor, Joan Slattery, so should be getting that back for some tweaking pretty soon. That one is also set in New Jersey and has some long-ago history embedded within more recent history. But, again, the characters sprung from the time and place and I just followed their voices. I also did a ton of research on the Sixties—which of course I lived through also—and realized what a huge decade that was . . . how important and far-reaching all of those changes really were—and are, even today.

TAR: What is your anticipated publication date for the Knopf book? Do you have a title for it yet?

JB: The projected publication date for the Sixties novel is 2009, but that could change as we’re still in the revision stages. Our working title for that book is Kaleidoscope Eyes.

An ALAN member for over twenty-five years, Jean E. Brown is Professor of English at Rhode Island College. She teaches undergraduate and graduate courses in YA literature. She also chairs the Alliance for the Study and Teaching of Adolescent Literature (ASTAL) and directs the ASTAL Summer Institute, Writing for Young People.