ALAN v35n3 - Teaching Memoir in the English Class: Taking Students to Jesus Land

Teaching Memoir in English Class:

Taking Students to

Jesus Land

“It’s taken me twenty years to grasp the truth of what happened in

Jesus Land

”

—

Julia Scheeres

(354)

Once in a great while—if you are lucky—a book comes along that stops you in your tracks, makes you turn around, question what you thought to be true, confirms your worst doubts, gives you immeasurable hope, and makes you a better person because of reading it. The first book to affect me in that way was To Kill a Mockingbird . The second was Jesus Land by Julia Scheeres, the winner of a 2006 Alex Award from the American Library Association (ALA).

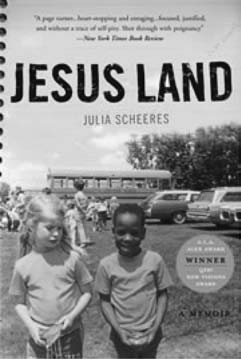

Figure 1. Jesus Land cover

Each year the Alex Award is given to ten books written for adults—published the year prior—that have special appeal to young adults, ages 12 through 18. Winning books must be written in a genre that especially appeals to young adults, potentially appealing to teenagers, and well written and very readable. Scheeres’ memoir duly fits each of these principles.

In this article, five of my students at the University of Alabama and I make a case for teaching Jesus Land in high school English classes, despite its inherently controversial and troubling religious and racial themes. Beginning with an overview of the book, we continue with the genre of memoir and why this particular title is important for students to read and study. Quotations are used from my students’ papers and written reflections from class; these appear credited to them by name (Isabel Arteta, Chad Mcgartlin, Kristen Stults, Elizabeth Welsh, and Charles White). From there, we provide an analysis of and justify teaching Scheeres’ work according to criteria set by Carol Jago (2004 ), Ted Hipple (nd), and Kenneth Donelson and Alleen Nilsen (2005 ). I conclude with my own personal reactions to Julia and her book.

What is Jesus Land About?

I came across Jesus Land by accident. While browsing the bookstore for a young adult novel, a book cover photograph totally captivated me: a young white girl and black boy in 1970s attire seemingly attending a school function (see Figure 1). This was no staged photo; this was real. What story was that one photo telling? Who were these two youngsters and how did they relate to Jesus? After looking at the back cover, I had to read it. And, read it I did—in nearly one sitting, staying up half the night to finish it.

Scheeres’ memoir is not so much her story as the story of her relationship with her adopted brother, David, growing up in a strict, religious household. As she states on her website (http://www.juliascheeres.com/),

Jesus Land is about my close relationship with my adopted brother David. It covers our Calvinist upbringing in Indiana and our stint at a Christian reform school in the Dominican Republic as teens. David, an African American, was adopted by my family in 1970, when he was 3. We were the same age. The book begins with our move to rural Indiana and our transition from a tiny Christian school to a large, public school where David and my other adopted black brother were the only minority students. It ends with David and me on a beach in the Dominican Republic. It’s a pretty wild ride between these two events. The central theme of Jesus Land is how race and religion tested our relationship. It’s a book about a couple of misfit kids learning to survive in a hostile environment, and the transcendence of sibling love.

The (Instructional) Promises and Perils of Jesus Land

Milner and Milner (2003 ) claim that autobiographies— the genre of which memoirs belong—“take us into the lives of others but at closer, more intimate range,” making us “eyewitnesses to actual events” (252). Milner and Milner assert that such works often catch adolescents’ natural interest about the lives of others. Specifically, memoirs differ from autobiographies in that “unlike autobiography, which moves in a dutiful line from birth to fame, omitting nothing significant, memoir assumes the life and ignores most of it. The writer of a memoir takes us back to a corner of his or her life that was unusually vivid or intense” ( Zinsser, 1987, 13, cited in Milner & Milner, 2003 ). In Jesus Land , Julia takes readers on a present-tense journey through her turbulent teenage years, a time which still profoundly affects her.

As English teachers, we have relatively few problems deliberating about fictional religious and racial issues: Hester’s scarlet A, Atticus’ defense of Tom Robinson, or Jerry Renault’s refusal to sell chocolates. What will hook readers in Jesus Land , no matter how close to or far removed from Scheeres’ upbringing, is, ironically, their connection to issues of race and religion seen and experienced by Julia and David. Growing up in America, children and adolescents confront and are confronted by race and religion on a daily basis. In fact, the complexity of the two real-life issues sometimes renders students (and teachers) silent.

times, students are mindful

of what they see, read,

and hear at home, on the

news, from their peers,

and on television and the

Internet.

Donelson and Nilsen (2005 ) note that “books that abashedly explore religious themes are relatively rare, partly because schools and libraries fear mixing church and state . . . it has been easier for schools to include religious books with historical settings” (132). Yet, they also stress that young adult literature does not exist in a vacuity. In these highly politicized times, students are mindful of what they see, read, and hear at home, on the news, from their peers, and on television and the Internet. Though a memoir, Jesus Land reads like a fiction novel with themes that would resonate with teen readers: a love story, survival, coming of age, family relationships, and abuse, to name a few. Such themes are found in the traditional and contemporary works currently read, discussed, and analyzed in English classes. As Kristin Stults states:

Many non-fiction books and memoirs address the issue of racism, but Scheeres’ memoir is unique in that it offers an up close glimpse of what racism was like as seen from the eyes of a white girl growing up with two black brothers. We get her unique perspective on experiencing the racism so closely, but also being separated from it because of her whiteness. This separation occurs even in her own household, where her brothers are routinely abused by their father, presumably because they are black, and Julia is spared even though she commits the same “sins.” In addition, the book deals with Christian fundamentalism. There are many memoirs where people have been scarred by their religious upbringings, but Julia’s is unique in that her parents were so full of zeal for their own church and for foreign missionaries, but utterly lacking in love for their own children. Her story is also different in that her parents went so far as to send her and her brother to a Christian reform school in the Dominican Republic. There, we get another perspective on the abuses committed in the name of Christianity.

Students and teachers can pay close attention to the way Scheeres is able to tell such a heart wrenching story while still maintaining her humor and even detachment from the situations at times. Students should study how she does this, and if it makes her story more or less effective. The way she uses a humorous and somewhat sarcastic tone at times makes the passages that are truly sentimental and heartfelt, that much more powerful.

Charles White and Chad McGartlin agree, adding that “readers can easily identify with such an explicitly true and real character as she deals with issues in a very internal manner . . . themes such as racism, religion and maturation in adolescence are consistently and smoothly woven throughout the book in a very eloquent manner as opposed to brief and superficial attempts at highlighting them as many books seem to do.”

Beyond typical classroom strategies such as literature circles and discussion questions, Jesus Land and Scheeres’ accessibility lends itself to deeper reader response activities. Charles and Chad offer several good ideas in Figure 2. Not withstanding the promising classroom instruction that could take place with this book, the very issues that make it so valuable are also those which might give some teachers, administrators, and parents concern. Patty Campbell (1994 ) claims that “sex, politics, and religion are the three traditionally taboo subjects in polite American society— and in young adult literature the greatest of these taboos is religion” (619). Religion, portrayed negatively in this case, is only the beginning. There is also sex, rape, abuse, and cursing. However, given that “any work is potentially censorable by someone, someplace, sometime, for some reason” ( Donelson & Nilsen, 2005, 368 )—even works as innocent as the dictionary and Judy Blume’s Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret — teachers have no more reason to worry about this book than they would otherwise.

Read the following information from the Escuela Caribe brochure. After reading the chapters that detail their experiences at the school, create a brochure of your own, using an ironic tone, advertising the schools’ negative aspects.

Do you have an adolescent who . . .

Rejects your family’s Christian values?

Is out of control? Has a poor self-image?

Is irresponsible, showing lack of character?

Runs with a negative crowd or has no friends?

Is unmotivated and failing in school?

Is disrespectful, rejecting your love and others?

New Horizons Youth Ministries can help.

Concept

Why in the Dominican Republic? Three reasons: atmosphere, culture shock, and distance.

Atmosphere

Escuela Caribe is set far away from the pervasive influences of American society: the materialism, the social ills, the negative peers, and the struggles in one’s family . . . .

Culture Shock

A change in climate, racial differences, geographic surroundings, friends, daily routine, and language all make adolescents remarkably more dependent upon others for direction. This also renders them more malleable . . . .

Distance

Living in a structured environment, teens start to appreciate Mom and Dad and begin to share their parents’ dream of a united family again . . .

READER RESPONSE 2

Each member of the family lives in his/her own special world. In Chapter 6, Julia is sleeping with Scott, her mother is alone in the kitchen, her father is relaxing in his Porsche, and David is languishing in the basement. Write a monologue for each of the characters to describe their thoughts at this point in the narrative. Compare to other students’ responses. Choose your best monologue and combine with those from classmates to perform a reader’s theatre presentation of the Scheeres household.

READER RESPONSE 3

What is most damaging to the family is what they do not say to each other rather than what they do talk about. Find a scene in the novel that you feel is the most important missed opportunity for communication of the novel. Rewrite the dialogue to include what the characters should/could have said to each other. Write in Julia’s style and stay true to the characters.

READER RESPONSE EXTRA CREDIT

Identify specific scenes in the novel and comment upon how the author’s style shapes the reader’s perception about the events. E-mail the author with particular questions that will serve to clarify the narrative, especially pertaining to her writing style.

Figure 2. Reader Response Ideas

adolescents do not approach

reading Pride and

Prejudice or Hamlet with

the same love and enthusiasm

that we do. . . . In

short: many students are

not reading at all. Works

such as Jesus Land will

entice readers of all ability

levels because of its

themes. A recent Education

Week (2007) story

confirms this, reporting

that today’s teen readers

often prefer the occasionally

dark and disturbing

contemporary trade books

precisely for their real-life

conflicts.

The reality is that many adolescents do not approach reading Pride and Prejudice or Hamlet with the same love and enthusiasm that we do. More importantly, a large number of secondary students cannot read such texts. Only three percent of all eighth graders read at the advanced level and nearly one-third of all ninth graders are two or more years behind the average level of reading achievement and need extra help ( Balfanz, McPartland, & Shaw, 2002; Perie, Grigg, & Donahue, 2005 ). In short: many students are not reading at all. Works such as Jesus Land will entice readers of all ability levels because of its themes. A recent Education Week (2007) story confirms this, reporting that today’s teen readers often prefer the occasionally dark and disturbing contemporary trade books precisely for their real-life conflicts. The dark themes in Jesus Land will appeal to many adolescent readers, even reluctant males, because they will address themselves “questions about justice . . . morality, and the existence of divinity” ( Hughes, 1981, 14 ).

Jesus Land as Young Adult Literature?

In my Adolescent Literature course, we use criteria set forth by Carol Jago, Kenneth Donelson and Alleen Nilsen, and Ted Hipple to examine and evaluate young adult literature for classroom use. After reading the assigned young adult novels, the class discussed them utilizing the three forms of evaluation because each focuses on a separate aspect of evaluating and teaching young adult literature: Jago’s to decide about whole-class versus individual study; Donelson and Nilsen’s for characteristics of the best young adult literature, and Hipple’s when discussing young adult literature. As Charles reflects, “It is important to follow a sound method to remind students, parents, and ourselves of a novel’s value in the classroom. Hipple, Jago, and Donelson and Nilsen ask important questions that help to clarify the significance of a novel.” In the sections that follow, using excerpts from the teachers’ final reflections, we analyze and break down the memoir to show how it corresponds to each set of criteria.

Jago's Test for Whole-Class Reading

Carol Jago, an advocate of teaching great literature with rigorous standards to all students, asserts that “there is an art to choosing books for students” (2004, 47); not all that are assigned and read should be included in the curriculum. Literature that works best for whole-class reading

- is written in language that is perfectly suited to the author’s purpose;

- exposes readers to complex human dilemmas;

- includes compelling, disconcerting characters;

- explores universal themes that combine different periods and cultures;

- challenges readers to reexamine their beliefs; and

- tells a good story with places for laughing and places for crying (47).

My students and I agree that Jesus Land fits all of Jago’s criteria; however, as teachers we know there will be issues. Isabel Arteta warns, “using this book as a whole-class book requires a mature, critical group of students.” In terms of language being suited to the author’s purpose, according to all four teachers, the book meets the first standard. Kristin writes:

In Jesus Land the author has an amazing ability to use language that is perfectly suited to her story. Writing about topics that are painful and disturbing, she never glosses over any of the events that took place. However, she is also able to describe them in such a way that the reader is aware of how she tried to remove herself emotionally from the situations she was facing. She is able to disturb the reader, to make us see the significance and the horror of the experiences without asking for pity or using overly emotional language. For example, when she describes being raped by her brother, Jerome, she says:I hear him lock the door and creep toward my bed. The mattress tilts under his weight. By the time he touches me, I’m far away. I breathe deeply, pretending to be asleep, falling through layers of numbness, sensation draining from my body like dirty bath water. My mind flits through a collage of images and thoughts—a horse galloping across a field of clover, the conjugation of To Be in French, the marigolds on Deb’s table. At some point, the collage fades, and time fades, but somehow I remember to keep breathing. (78)In this passage, her language is appropriate to that of a teenage girl. However, it is also powerful and poetic, expressing emotions that perhaps she can only now, as an adult, put into words.

Jago’s second condition, whether a work exposes readers to complex human dilemmas, is also met. Again, I use Kristin’s response in this area.

This book does nothing if not expose the reader to complex human dilemmas. The reader must confront issues of religion, racism, incest, rape, sexuality, and human relationships . . . Julia is torn between being the sister of her two black brothers and being the favored white daughter. She feels sorry for her brothers, that they are treated unfairly by their peers and by their own parents, but at the same time she hates Jerome for the sexual abuse he inflicts on her, and feels resentful toward David when his presence makes popularity at school unattainable. In addition, Julia desires a relationship with her parents, desires to hear them say that they love her, but she also hates her mother for her neglect, and hates her father for the physical abuse he inflicts on her brothers. She also hates their hypocrisy, the way they prioritize foreign missions above their own family, and put on an air of piety at church. She is brutally honest when she talks about the dilemmas that face many teenage girls.

is the core intent

and purpose of the memoir.

Scheeres has eloquently

lived through an

entire cauldron of human

drama and dilemma.”

Chad agrees, commenting that “complex human dilemma is the core intent and purpose of the memoir. Scheeres has eloquently lived through an entire cauldron of human drama and dilemma.”

One common complaint from high school students is that the characters in books they read for school have nothing to do with them. Even in my adolescent literature class, the 20- to 30-year-old students had a hard time relating to some of the characters in the novels they read. However, we all agreed that the characters in Jesus Land are compelling, disconcerting, and well-developed. According to Isabel:

The character development in Jesus Land is so good that only after a few pages you feel you could recognize them [the mother, Jerome, the father] if you met them on the street. “She’s in one of her moods; we knew it as soon as we returned from our bike ride. She was in the kitchen, ripping coupons from the newspaper, her lips smashed into a hard little line. She didn’t say hello and neither did we. We took one look at her and went downstairs; it’s best to fall under the radar when she gets like this” (16). “The door implodes sucking David into the room. Jerome stands there, tall and glowering in the shadows. He has turned off the intercom, and the blinds are shut. The room smells sour, like dirty laundry. I follow David inside, and Jerome locks the door behind me. He’s several shades darker than David, almost coal-colored. No one would confuse them for brothers” (64). “But somewhere along the line he dropped out of our lives . . . He became a stranger to us, a stranger who comes around to mete out punishment. A stranger whose presence we’ve come to resent” (68).

“Even the minor characters,” says Kristin, “are all painfully real. Scott, Julia’s boyfriend, begins as an attempted gang rapist, then turns to someone who appears to want to date Julia just for sex, and then ultimately professes his love for her and wants to marry her. These changes and contradictions all make the characters seem very real.” This point validates the need for good memoirs to be taught—the characters are real, with real stories to tell and real-life connections to be made.

We concur, too, that this memoir explores universal themes and combines different periods and cultures. Isabel makes the point that “even though the story is set in a specific time and place, the themes explored are timeless and universal. Cultural and religious struggle—as well as bigotry and hypocrisy—plague us today as clearly as 30 years ago.” There is an immediacy of themes, too. “The book discusses the difference between their lives at Lafayette Christian and when they switch to the much larger public high school . . . the culture of school, of their Calvinist church, of their dysfunctional home and of the reform school” (Kristin).

An Interview with Julia Scheeres

Elizabeth Welsh

What caused you to finally sit down and write

Jesus Land

?

Jesus Land

had been percolating inside of me for 20 years before I finally sat down to write it. I think gaining the perspective and wisdom of age helped me, as well as becoming a professional writer (I’m a journalist by trade). David’s story had been weighing on me all that time, and I felt compelled to tell people about him, about how beautiful and tragic and hopeful a person he was. Immortalizing him in a book was the best way to get his story out there.

Did you have concerns about how it would be received by your family?

No. My main concern was honoring my brother’s memory. My family’s reactions didn’t really factor in—I was going to write the book no matter what.

Who do you consider your biggest fan/supporter?

My husband, Tim Rose. He helped me through some dark days when I had lost hope of selling my book.

Was there ever a point where you felt discouraged while writing?

Sure, when I had to relive (in my mind) a scene in my mind where David was physically abused. After completing such a scene, I’d go lie down on my bed and cry.

Was there any one method that helped you put your story onto the page?

Not really. Aside for forcing myself to sit still and concentrate and to aim for at least 700 words a day when I was in writing—not editing—mode.

When you first sat down to write

Jesus Land

, who was your imagined audience?

I didn’t think of a readership. I just thought of David and our experiences together and my need to record them.

If you were pitching your memoir to a young adult reader, what would you say to get them hooked?

Oh, tough question. This is the story of a couple of misfit siblings whose relationship is tested by racism, religious hypocrisy and toxic adults and who emerge stronger because of it.

What does winning the ALEX Award mean to you?

It means that my book appeals to young adults as well as old adults, which means more people will read it and get to know my brother.

What would be your response to censorship issues involving schools and parents in light of the language and mature themes presented in

Jesus Land

?

I think the themes in

Jesus Land

are mild compared to what high school kids are doing these days. And my book is an honest portrayal of themes that do happen to kids, but which adults prefer to ignore or brush under the carpet, including teenage drinking and sex.

Was there a reason behind minimizing the roles of your parents within the book? (There’s actually a formula that many YA authors follow which calls for the absence of parents)

I wanted the focus to be my relationship with my brother, not my parents.

Do you receive letters/emails from teens? What do they have to say about your memoir?

I get a lot of emails from people who felt like they were somehow misfits too, growing up. Because of their religious beliefs, skin color, etc. A lot of people write to say they really felt like they knew David after reading my book and wished they could have met him in real life. It’s very flattering.

Do you have advice for teens who may have a story to tell but only have limited chances to write narratives in school?

Keep a vivid journal. Don’t show it to anyone. You’ll love having it in 10, 20, 30 years. Time is so fleeting. Having an artifact of your younger self is precious.

What kind of writing did you do in school? What kind of English student were you?

Depends. I wasn’t a good student in high school but while getting my Master’s degree in Journalism, I did a lot of writing, obviously. I’m more interested in modern writing than in the classics, possibly do to my impatient nature and background as a no-frills reporter.

How did writing

Jesus Land

as a memoir make it more powerful than a fiction presentation?

Because it’s true. Amazing true stories are exponentially more interesting than amazing made-up stories.

Does the idea of having your memoir taught as a classroom text appeal to you? How do you feel about the need for memoir/autobiography in the English classroom?

Sure. I think it’s important for students to read true-life stories that either resonate with their own lives or are incredibly different. It gives them a better sense of self and place. Reading autobiographies may also make them feel a little less lonely, knowing that others have also had difficult lives and survived.

deal with their own seri-

ous problems at home and

at school . . . in the end,

they don’t triumph over all

adversity, but they are

able to achieve freedom.

“All through the book the reader is challenged to reexamine beliefs, challenge value systems, at least revise moral standings” (Isabel). Organized religion is portrayed in a negative and hypocritical light: Julia’s parents are zealot-like, yet they emotionally and physically abuse their children, and Escuela Caribe more closely resembles a concentration camp than a Christian reform school. “Maybe this characteristic of the book is the one that may make the book difficult to use as a whole-class assignment. Young adults who read this memoir have to be mature and critical, ready to evaluate the novel within its time and place and then extrapolate from it that which is meaningful to them” (Isabel).

The last criterion, telling a good story with places for laughing and crying, is met, despite the harshness and seriousness of the book. Charles writes that “the last criteria is my favorite . . . in Jesus Land , the moment when [the] brother and sister leave the camp for the first time is the funniest because they both started spouting more profanity than they had ever used in their lives—words like ‘papaya ass’ made me laugh.” Kristin did not laugh, but rather found “poignant moments.” She found many moments for crying—Julia’s repeated rapes, their mistreatment at Escuela Caribe, David and Jerome’s physical abuse, and David’s death. To quote her directly,

Even the beautiful moments though, were clouded by a feeling that “this cannot last.” It was beautiful to see brother and sister together, finally free of their bondage, but the whole tone of the book was such that doom seemed imminent at all times. That being said, there were moments that were humorous, even if it was more of a sarcastic than laugh-out-loud kind of humor. The most memorable was when the Sunday School teacher tells their class that they can’t “jack off with Jesus.” Moments like this are plentiful, and make you shake your head.

Donelson and Nilsen’s Characteristics of the Best Young Adult Literature

In developing their characteristics of the best young adult literature, Donelson and Nilsen (2005, 14-35 ) referred to numerous sources, including other best book and awards lists (e.g., Printz, Newbery, School Library Journal ) and professional organizations (such as ALA). Using this list as a guide, we determined that even though it is a memoir aimed at adult readers, Jesus Land meets the characteristics, although there were some slight disagreements in a few areas.

- Young adult authors write from the viewpoint of young people . This novel does an amazing job of capturing the struggles of a teenage girl as she grapples with many issues. Her voice and perspective are very clear and easy to identify with. [Written] as a memoir, it is easy to feel that the experiences and feelings are the direct views of the author’s teen years. (Chad)

- In young adult books, parents are “removed” so that the adolescent(s) can take the credit . In this book David and Julia get all the credit. Though they are not orphans, they lack all parental support and guidance. The parents are emotionally out of the picture, and David and Julia are left to deal with their own serious problems at home and at school . . . in the end, they don’t triumph over all adversity, but they are able to achieve freedom. (Kristin)

-

Young adult literature is fast-paced

. Many instances in the book are absolutely captivating. This book was definitely hard to put down, yet did so without sacrificing depth and description. (Chad)

Sometimes the story runs with the speed of bikes, at other times it almost screeches to a halt as the characters are faced with more trying times. “His numbness, his refusal to accept what is happening by refusing to react—all this is familiar. Things are done to you and you can’t do anything back. And so you play dead. Because if you don’t acknowledge something, it isn’t real. It doesn’t happen” (308). (Isabel) - Young adult literature includes a variety of genres and subjects . This novel used a variety of intimate and personal themes to attract the reader. I found the elements of religion, race, sex, and family to be profoundly impacting and very well developed . . . readers could easily use these themes to segue into meaningful guided discussion. (Chad)

- Young adult literature includes stories about characters from many different ethnic and cultural groups. Jesus Land definitely addresses different ethnic and cultural groups. Obviously there is the issue of a white family “raising” two black sons. But there is also the issue of the conservative and religious culture in Indiana, contrasted with its overt racism and hypocrisy . . . we also get a glimpse into Dominican life and culture. (Kristin)

- Young adult books are basically optimistic, with characters making worthy accomplishments . Julia is an extremely memorable and gracious character. The book is full of down moments, but her character and struggles are amazingly positive as is her selflessness and attitude towards the array of negativity in her life and journey. This type of perseverance seems a great way to attempt to connect to borderline and troubled students. (Chad)

-

Successful young adult novels deal with emotions that are important to young adults

. The emotions dealt with—wanting acceptance, not fitting in, getting taunted, making friends, loving and hating siblings, not relating to parents, finding a first romantic relationship and dealing with its complexities, and challenging authority—are all things that young people can relate to. (Kristin)

Although a higher-level text, the situations and emotions in the book are very applicable and relevant to today’s high school student . . . the biggest strength of the book is the realistic emotions and reactions attached to these circumstances . . . all readers can identify with this. (Chad)

Ted Hipple’s Discussion Method

I have taken one of Ted Hipple’s assignments 1 , used for discussing The Catcher in the Rye , and modified it for use with any novel. His ten questions center on more personal reactions, such as how the novel agrees with a reader’s personal beliefs and its emotional impact (See Figure 3).

EVALUATION OF [INSERT TITLE]

Ted Hipple, one of the leaders in young adult literature, used the following points for evaluation when discussing young adult literature. One of the expressions he used was, “de gustibus non disputandum,” which basically means there’s no accounting for taste!

- clarity—how clear is the novel?

- escape—how much can you lose yourself in it?

- reflections of real life—how true is the novel to human fact, to human nature?

- artistry in details—how artistic are the details of the novel? (name some your particularly liked)

- internal consistency—do the parts and the whole fit together?

- emotional impact—what is the impact of the novel on you emotionally? (think in terms of duration, intensity, recurrence, and universality)

- personal beliefs—how does the novel square with your personal beliefs?

- significant insights—are the ideas in the novel significant?

- shareability—how much do others agree with you on these judgments?

- yea/boo—why can’t I explain my feelings about this work?

Figure 3. Hipple Evaluation (adapted for classroom use)

From reading the teachers’ analyses and evaluations of the novel, it is clear that Hipple’s set of questions “squared” with them the most and they produced writing nearly as beautiful as Scheeres’.

Isabel’s final paper introduction says it perfectly: “it is really important to state . . . that when a book touches you in so many different ways, when you feel for the characters so deeply, when you trudge with them through the muck and when you rebel with your own impotence to change the world, an objective evaluation is far from attainable. That being said, the Ted Hipple criteria are probably better suited for analysis than any other.”

-

How clear is the novel?

Jesus Land is crystal clear because the author is not simply making up a story. Instead, she is speaking from the heart and the events reflect her personal involvement and honest depiction of her vivid experiences. (Charles) -

How much can you lose yourself in it?

It is difficult to say if you can lose yourself in the book, or you want to escape from its story. It is one of those books you do not want to stop reading, while at the same time you really want it to stop; you want to go back to the apparent normality of your own life. (Isabel)

This novel is easy to become lost in. As discussed in our literature circles, even the first two paragraphs and subsequent introduction to the setting and characters pull the reader in from the beginning with imagery of a cow shit stench slamming up their noses and the “This here is Jesus Land” etched plywood. It was the hardest novel to put down that I’ve read in a long time. (Chad) -

How true is the novel to human fact, to human nature?

The book invites the reader to reflect on every aspect of human nature, especially in the enormous potential for evil and good that each one has and how each one chooses to live it. As for human fact, a memoir so devoid of pity, brimming with extremely detailed accounts of a very human life in a very inhumane world cannot ring truer. (Isabel)

In Jesus Land , every sentence is testimony to the horrors and wonders of human nature. (Charles) -

How artistic are the details of the novel?

The details are incredibly well-done, though to say artistic makes it sound like they were beautiful and almost unreal. That seems like a stretch for a book this brutal. They were artistic in that they made the story so real, so like real life, like the real teenage years. For instance:

As soon as Reverend Dykstra pronounced the final “amen” and bustled down the aisle toward the narthex, Rick and I would rush up the back stairway to the windowless attic, where we’d feel our way through fusty stacks of Psalter Hymnals and the cool satin of choir robes to a cushionless sofa. There, we’d sit facing each other in the darkness, taking turns running a fingertip over each other’s palms, without speaking, as bats fluttered overhead and cars honked faintly in the parking lot. After Rick’s glow-in-the-dark wristwatch marked five minutes, we’d slip back down the staircase to reunite with our families.

These fingertip caresses were exquisite, amplified by our inability to see the lust and embarrassment in each other’s faces. There was only a tingling sensation and our open-mouthed breathing. (84) (Kristin)

-

Do the parts and the whole fit together?

All of the thoughts and feelings are brought together with extreme consistency, each new turn providing more foundation to support the arguments made (from “In God We Trust” to “Trust No One” to the “Epilogue”) (Isabel) -

What is the impact of the novel on you emotionally?

As you go through the story, recurring thoughts of helplessness and disbelief take hold. How could they have survived this? When are those religious values they talk about so much going to engage, to become actions? Where are the good people, the normal ones? Are there any good normal people? Emotional impact is enormous. (Isabel)

On the most basic level, I felt anger. I squeezed the book many times. I stopped to breathe and collect myself a few times. I almost fell asleep holding the book at night after I finished it, like it was a physical being that I could hold and console and relate to. (Chad) -

How does the novel square with your personal beliefs?

This novel really affected me in a positive, yet harsh way . . . I almost feel sad that it didn’t shock me . . . Instead, it fell right in line with how I think our society has deteriorated and left teens to feel scared or embarrassed to make decisions that are contrary to one or all of the predominant social constructs in their environment. (Chad) -

Are the ideas in the novel significant? How much do others agree with you on these judgments?

Definitely. (Chad)

When we discussed the book, we found absolute agreement in almost all of our opinions. The general statement was that the book was a powerful, well-written account of a very sad life. (Isabel) -

Yea/boo?

It was hard to read, but I’m glad I did. (Kristin)

The final conclusion: YEA! Even though you end up totally devastated when you finish the book, you want to read it again. (Isabel)

Conclusion

felt anger. I squeezed the

book many times. I

stopped to breathe and

collect myself a few times.

Shortly after reading the book, I emailed Julia asking if one of my students, Elizabeth, could interview her for her class paper (see p. 74). With kindness and trust not often found in this world, Julia emailed back with her phone number letting me know I could call any time. That began a correspondence that continued through Elizabeth’s interview, my two-week stint in a third-world country, and a busy semester. It is precisely this personal, friendly, unguarded persona that makes Jesus Land what it is. As a reader, you (I use this term on purpose) feel a personal connection to Julia, David, and their story. It is as if each and every reader is a “you” who can expect a phone call or email from Julia at any time.

Julia, and her book, hold true to the claim that through them, we are introduced to “real people” and “develop a partnership with the narrator-subject as we receive the self-disclosure and willing confidences that are so hard-won in our everyday friendships” ( Milner & Milner, 2003, p. 252 ). Such relationships are rare . . . and so is a book as powerfully poignant as Jesus Land .

1 After Ted died in 2004, I found this assignment. I am not sure if he created it or “borrowed” it from another source.

Lisa Scherff is assistant professor of English education at The University of Alabama and coeditor of English Leadership Quarterly . Her research focuses on adolescent literacy and teacher preparation, induction, and mentoring.

Isabel Arteta-Durini was born in Ecuador. She studied Animal Science at Cornell University, received an MBA from the Universidad San Francisco de Quito, and is currently finishing a master’s degree in education from the University of Alabama. She teaches 10th-grade biology at the American School of Quito.

Originally from Atlanta, Chad McGartlin serves as the humanities department head at the American School of Quito (Ecuador) where he teaches history and Theory of Knowledge. He also taught in Nanjing, China, and Mexico City, Mexico. Chad holds a bachelor’s degree in Social Science Education from Kennesaw State University and a master’s in secondary education from the Univ. of Alabama.

Kristin Stults is currently a master’s degree student and stay-at-home mom of two boys. She lives in Durham, North Carolina.

Elizabeth M.Welsh is a preservice English teacher at the University of Alabama.

Charles White taught high school English in California before arriving at Colegio Americano in Quito to teach IB English. He is currently teaching English and Cinema Studies in Istanbul, Turkey, at Uskudar Amerikan Lisesi.

Works Cited

Balfanz, Robert, James McPartland, and Alta Shaw, A. Re-conceptualizing Extra Help for High School Students in a High Standards Era . Paper commissioned for “Preparing America’s Future: The High School Symposium.” Washington, DC, 2002.

Campbell, Patty. “The Sand in the Oyster.” The Horn Book Magazine , 70.5 (1994): 619-623.

Donelson, Kenneth, and Alleen Pace Nilsen. Literature for Today’s Young Adults (7th edition). New York: Pearson Allyn Bacon, 2005.

Hughes, Dean, and Kathy Piehl, K. “Bait/Rebait: Books for Young Readers that Touch on Religious Themes do not Get a Fair Shake in the Marketplace.” English Journal , 70.8 (1981): 14-17.

Jago, Carol. Classics in the Classroom: Designing Accessible Literature Lessons . Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2004.

Manzo, Kathleen K. “Dark Themes in Books Get Students Reading.” Education Week , 26.31 (2007): 1, 16. [Electronic Version].

Milner, Joseph O., and Lucy F. Milner. Bridging English (3rd Ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill Prentice Hall, 2003.

National Council of Teachers of English, and International Reading Association. Standards for the English Language Arts . Urbana, IL, and Newark, DE: NCTE. 1996.

Peire, Marianne. Wendy S. Grigg, and Patricia Donahue. The Nation’s Report card: Reading 2005 (NCES 2006-451). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, 2005.

Scheeres, Julia. Jesus Land . New York: Counterpoint, 2005.

Zinsser, William, ed. Inventing the Truth: The Art and Craft of Memoir . Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1987.