ALAN v40n1 - Looking into and beyond Time and Place: The Timeless Potential of YA Lit in a Time of Limited Opportunity

Looking into and beyond Time and Place: The Timeless Potential of YA Lit in a Time of Limited Opportunity

Literature has the potential to allow students and teachers to explore, understand, critique, and emulate alternative ways of living and being reflected in times past, present, and future. Historical fiction exposes readers to stories that are simultaneously real and unreal. They are drawn from the past and shaped by writers living in present history that will soon pass; interpretations remain forever in flux. Yet, these stories "transcend setting in their persistent reminder that the human experience is timeless. That these writers write (and we readers read) these novels attests to the human spirit to question, to explore, to understand the connections that bind us—regardless of the time and place in which we live" ( Glenn, 2005 ).

Literature set in contemporary times, as well as the future, affords readers and teachers opportunities to reflect upon current issues—personal, local, and global. It "helps shape our perceptions of people and places in the world. In discussions of literature we have an opportunity to explore the complexity of human difference and human relations, and the conclusions we reach matter. They matter because they tell us who we are and who we can become" ( Pace &Townsend, 1999 , p. 43).

Quite simply, literature matters. We worry, however, that the pervasive external forces that encourage unnecessary simplification and scripted approaches to reading instruction might limit—or eliminate—opportunities for using literature to its full potential. Teachers, particularly those newer to the profession, are increasingly working to navigate the tension between what they perceive they must do and what they know is best for their students. To provide a model that pushes back against attempts at standardization and instead trusts students and teachers and their ability to think critically and creatively, we advocate an approach that contextualizes literature in a larger conversation and inspires complex and even contentious dialogue, discussion, and contemplation among students in our classroom communities. (Ironically, it is also likely to prepare them for state exams in more effective and motivating ways than test prep exercises can.)

Curricula centered on essential questions , "questions that are not answerable with finality in a brief sentence [and aim to] stimulate thought, to provoke inquiry, and to spark more questions—including thoughtful student questions—not just pat answers" ( Wiggins &McTighe, 2005 , p. 106), and/or big ideas , "themes, issues, and concepts that face teachers and students alike in the 21st century" ( George, 2001 , p. 81) have the potential to ensure that what matters most about literature makes its way into our classrooms. While this approach is not new, this article reminds us of what is possible in a time when teachers are often asked to achieve the impossible.

Given our passion for and advocacy of young adult literature (YA lit), in particular, we draw upon titles for adolescent readers that invite us to discuss why and how to use this literature in ways that foster rich contextualization, especially by posing questions and examining worthwhile ideas. We include references to historical, contemporary, and future–oriented YA fiction that has been well received by middle and high school students and teachers in various regions of the United States, as well as recently published titles that are perhaps less familiar but equally compelling; these titles offer new ways of thinking about old texts and have the potential to become mainstays in the classroom.

In each section, we annotate multiple texts set in the past, present, and future. We also more deeply examine an additional title by a) demonstrating how essential questions (EQ) and/or big ideas (BI) might be used to guide curriculum planning and underpin instructional units centered on this title, and b) providing sample activities that encourage exploration of these EQs and/or BIs within the English classroom. To allow readers to see the potential for both frames— questions and big ideas—we model both in the discussion of the differing YA titles throughout.

Looking Back: Historical Fiction

Traditional textbooks as well as many historical primary source documents fail to capture the voices of young people who lived in the time period being represented. Historical fiction writer Christopher Collier (1987) suggests that "there is no better way to teach history than to embrace potential readers and fling them into the living past" (p. 5). Indeed, historical novels can bring history alive for children and adolescents ( Johannessen, 2000 ; Lott &Wasta, 1999 ). Literature and literary materials "convey well the affective domain of human experience. The realism achieved through vivid portrayals in works of literature stirs the imagination of the young reader and helps develop a feeling for and an identification with the topic being studied" ( Jarolimek, 1990 , p. 198). By engaging with historical fiction, adolescent students are encouraged to be "better informed, make good decisions, and become responsible citizens, willing to intervene where necessary to promote human dignity and fairness" ( Rice, 2006 , p. 20).

Briefly Annotated Titles

Books set in the past generate a richer understanding of what has come before, invite readers to consider connections to their present, and encourage them to ponder new visions of the future.

Chains

(

Anderson, 2008

), for example, reeducates readers about the American past by highlighting quotations that demand careful consideration. When readers learn that Ben Franklin wrote, "Our slaves, sir, cost us money, and we buy them to make money by their labour. If they are sick, they are not only unprofitable, but expensive" (

Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser

cited in

Chains

, p. 157), they might understand Franklin as more complex than the fearless inventor and patriot portrayed in their elementary school readers. At the same time, Chains promotes questioning of democracy and the democratic process—both at the time of our nation's founding and today—and thus demands consideration of tomorrow. As readers, we were pressed to consider whether or not the founding fathers would have achieved much of anything had they worked under the scrutiny of the modern media. Could they have sequestered themselves and worked in secret, or would the American public, used to immediate access to information, demand a right to know what was transpiring as it transpired?

After Tupac and D Foster ( Woodson, 2008 ) offers readers quiet, albeit rich, contemplation of issues of race and perception. Set in the recent past, one that grows more distant with each generation of student readers unfamiliar with Tupac and his music, the novel describes a friendship that develops between three teen girls as they share their passion for Tupac's music and attempt to make sense of a world that often confounds them. The story offers a counter–narrative of the black experience ( Brooks, 2009 ; Delgado, 2000 ; McNair, 2008 ), highlighting strong family connections, a safe and secure neighborhood, and intellectually curious young people, all of which undermine false assumptions that often accompany deficit–oriented portrayals of people of color in our contemporary world.

While much historical fiction centers on America's past, several texts introduce readers to histories of people beyond our borders. A Single Shard ( Park, 2001 ), set in twelfth–century Korea, depicts the life of a ten–year–old orphan apprenticed to a gifted potter who receives a commission from the royal palace. This story of courage, sacrifice, and selflessness is not only rich in history and culture, but also in its potential for encouraging readers to consider privilege and power, relative morality, and freedom and responsibility.

Looking Deeper:

Tree Girl

Tree Girl

(

Mikaelsen, 2004

) offers a particularly powerful teen voice that provides depth and reality to a difficult historical event. Mikaelsen fictionalizes the lived experiences of a girl forced to flee her Mayan village in Guatemala upon the outbreak of war and travel to Mexico to find safety. Gabriela loves to climb trees, to perch upon limbs she fears might not hold her weight. This talent saves and condemns her; she escapes death but is left to face life. The images she witnesses are hard to bear. Children are pulled from the arms of their mothers. Animals are used as target practice. Old women are forced to strip and behave like circus animals or be shot. Gabriela cannot reconcile this violence with what she knows of human nature. She wonders, "Surely humans could not be so cruel" (p. 134).

The novel, however, retains hope, as Gabriela fights back in ways both big and small. She endures an arduous trip down the tree, away from the village, and into a refugee camp. When she arrives, she finds hundreds of people living in squalor, with vacant eyes and seemingly few prospects of survival, much less a return to their former existence. With small steps, however, Gabriela improves the situation, refusing to believe that this is all that is left.

Big Ideas

BI: Historical fiction can educate and reeducate by complicating what we think we know.

To help students gain more complex understanding of the events that undergird the novel and this period in history, teachers might ask them to review US foreign policy around this event. As a result of the Freedom of Information Act, over 5,000 documents chronicling the involvement of the US government in the 1954 coup in Guatemala—the war that sends Gabriela from her home—have been released (

http://www.foia.cia.gov/guatemala.asp

). Students might work in small groups to use these documents to build cases to support or condemn US involvement. In doing so, they will be asked to consider issues of morality, motive, and cause and effect.

To assess understanding and provide students a meaningful opportunity to express these understandings, teachers might ask them to defend their cases in the hosting of a mock trial or whole–class debate. Students might choose to examine whether or not the knowing participation of the US government in the Guatemalan coup of 1954 was justified. As members of each student group share their arguments, other students will benefit by gaining additional knowledge and experiencing the multiplicity of perspectives that exists in the context of complicated issues.

BI: Historical fiction can build connection to other people, times, and places and reinforce our shared existence as members of a human community.

Unfortunately, several contemporary examples of tragedies similar to those described in Tree Girl exist today. The examination of such events might provide connection to the novel by encouraging students to understand the reality of Gabriela's world; the story is fiction, but the history is real—and there are others like her who suffer today. Teachers might focus on recent violence between Christians and Muslims in Nigeria, for example (

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/35759877/ns/world_news–africa/

), fostering discussion of the underlying events, power relationships, politics, and philosophies that allow, even encourage, such happenings in our shared world.

Students might then apply these understandings and explore further the lives of those involved in such tragedies by engaging in a writing activity designed to encourage empathetic thinking:

- Select a character from the novel, a person we have studied in our exploration of contemporary events, or a real or imagined person of your own creation about whom you want to know more

-

Imagine life as this person by considering in draft writing how the character would respond to these questions (and any others you wish to generate):

- When, where, and with whom do I live?

- What are my fears? Regrets?

- What are my hopes? Passions?

- How do I see myself? How do others see me?

- What do I wish to change about my life? Do I have the power to enact this change?

- Go deeper by placing your person in a scenario you think might prove intriguing. Imagine, for example, that your person suffers the loss of a loved one, is asked to commit a crime, or has the choice to leave home. As you draft, consider your person's physical, emotional, and psychological response.

- Revisit the writing generated thus far. While in character, use this information to engage in a whole–class discussion focused on the following quotation: "‘To understand all is to forgive all' it has been said; and it is sometimes even something more. It is to sympathize, and even to love, where we cannot yet fully agree. And therefore, perhaps, even the feeblest little attempt to make human beings understand how and why their fellows feel as they feel and are as they are, is not quite nothing." ( Olive Schreiner in The Dawn of Civilisation , p. 00)

Assuming the persona of a character who inhabits a land and culture unfamiliar to students requires care and sensitivity, particularly in the attempt to avoid privileging American culture in a way that unfairly critiques or condemns those in other communities. However, this process of encouraging an empathetic stance also fosters both recognition of cultural difference and respect for alternate ways of knowing and doing.

BI: Historical fiction can give emotional reality to names, dates, and other factual information, letting us imagine the voices of those who lived in other places and times, voices that have sometimes been silenced in official accounts of history, ideally inspiring us to honor these voices and generate a better future.

After reading

Tree Gir

l, students might understandably feel helpless in their inability to elicit global change. With this helplessness often comes the development of a savior–oriented mindset grounded in the assumption that we, as westerners, have easy answers to complex problems. To help students better understand the difficult realities of social change, both globally and locally, and how perspectives are shaped by the lens through which we see, teachers might ask students to engage in participatory action research (PAR) to heighten awareness of their own community and learn manageable ways to foster change and build hope (

McLaren &Giarelli, 1995

;

Morrell, 2004

).

After reading and discussing texts centered on social inequities in their city, eleventh–grade students in Los Angeles, for example, addressed their feelings of hopelessness by responding "from the position of agents of social change" to "engender feelings of possibility" ( Duncan–Andrade, 2007 , p. 28). They interviewed community members, generated observational notes, and collected video footage to document oppressive conditions identified in their community. Data were compiled into a written report that was shared via presentations to constituent groups within the community. Students might choose to host a town hall meeting or screen a student–generated film to share their work. Whatever the forum, PAR affords teachers a meaningful, practical model for encouraging students to be problem solvers who refuse to allow helplessness to paralyze them, teaching them to instead think beyond what others believe possible and to advance options for change.

Looking Ahead: Future–Oriented Texts

Young adult texts set in the future (both futuristic and science fiction tales) provide readers distance and connection. As Donelson and Nilsen (2004) suggest, in future–oriented fiction, "Contemporary problems are projected hundreds or thousands of years into the future, and those new views of overpopulation, pollution, religious bickering, political machinations, and sexual disharmony often give readers a quite different perspective on our world and our problems today" (p. 213). This consideration of new and different perspectives might challenge readers to critique the social systems to which they claim (or inherit) membership. Books set in the future present the possibility of what may come while fostering reflection on how we might get there given our current and past realities, emphasizing the relationship between choices and the consequences that result.

Briefly Annotated Titles

Future–oriented fiction encourages readers to consider multiple visions of how life might look for themselves and the generations that follow. They are exposed to creative representations of time and place that challenge, extend, and redefine what they believe is possible.

The Declaration

(

Malley, 2007

), for example, paints a society in which inhabitants have the option of extending life indefinitely by taking a drug called Longevity. Those who opt out of the medication are punished if they produce children, a responsibility that resides with the state. Any unauthorized children, or Surplus, are placed in training centers where they learn to serve those who choose to play by the rules. Readers are thrust into a community in which the quality of life is diminished (albeit prolonged), power is held by those who run the pharmaceutical companies, and conformity is celebrated at the expense of free thinking.

Exodus ( Bertagna, 2008 ) also invites readers to consider a world unlike their own, one in which the ice caps have melted and water has taken over the land, forcing citizens to flee their homes and seek safety on the sea. As 15–year–old Mara battles for basic resources, she witnesses the worst humankind has to offer—greed, selfishness, violent urges, and a deepseated lack of empathy. As the physical earth suffers from the consequences of human excess, humans lose their humanity.

Little Brother ( Doctorow, 2008 ) lures readers into a vision of the near future when technological innovation offers convenience and flexibility but also limits personal freedoms. The novel's tech–savvy teen protagonists find themselves near the site of a terrorist attack. Despite their innocence, they become fugitives against a seemingly democratic government that feels threatened by their knowledge and suspicious behavior. They suffer psychological torture and humiliation during an interrogation, lose personal privacy when their computers and phones are tapped, and suffer the loss of their right to assemble in protest.

In addition to exposing readers to these alternate realities, future–oriented texts foster reflection on how we might achieve—or avoid—such visions of the future given our current and past realities. The Declaratio n reminds readers that our ability to think for ourselves, if we harness it, might be our greatest weapons against social strife resulting from the stratification of power. Exodus warns against global warming and suggests the need to treat our existing world with care. And Little Brother entreats us to think critically about the technological advances we often accept without question.

Looking Deeper:

Feed

Feed

(

Anderson, 2004

) provides rich opportunities to both expose readers to an alternate world and encourage them to evaluate what they witness in the context of their own current and potentially future realities. The satirical novel is set in a future in which television and computer connections are hardwired into the human brain upon birth, thus allowing corporate and media conglomerates access to an always–captive market. The novel's protagonist, Titus, is as inarticulate and naïve as his peers, never questioning the world into which he was born. When he travels to the Moon and meets Violet, a home–schooled teen who critiques and resists the networked world, he is challenged in ways unfamiliar and uncomfortable. Readers experience his confusion and frustration and are forced to consider the implications of a society overly dependent upon technology at the expense of independent thought and appreciation of small joys.

Big Ideas

BI: Future–oriented fiction provides distance that allows for honest critique. We are not reading about our existing world, so we can see more objectively.

To encourage rich textual analysis and allow for distanced critique of another world (such as immediate gratification at the expense of free thinking or a stifling of creativity and independence), teachers might invite students to record several short passages from the novel that contain a behavior, event, idea, etc. that they find troubling. Students might then reflect in writing upon these passages, considering in particular what they find disturbing and why this might be so. A whole–class discussion of these passages and responses might then ensue, fostering critical thinking in and beyond the text.

BI: Future–oriented fiction embodies the potential "next iteration" of our society, giving us a glimpse into what might be, for better or worse.

The above activity will likely reveal just how easy it is for us to critique the fictional society described in

Feed

. To encourage students to turn the mirrors on their own world, teachers might have them engage in the following activity:

- Over the next 24 hours, catalog your use of technology. Create a chart that demonstrates the technologies you use, how long you use them, and for what purpose(s).

- Over the 24 hours following step one, attempt to avoid the use of technology altogether. Reflect in writing on the difficulties, benefits, surprises, etc. that resulted.

- Use these experiences and your written reflection to participate in a whole–class discussion centered on the following question, "Is our modern society helped or hindered by technology?"

BI: In future–oriented fiction, our present often becomes written as the past. We can evaluate how our choices in the here and now might come to fruition. There are consequences for our actions; we are accountable for the world we leave to the future.

To help readers give thought to how our actions reflect an investment in our collective futures, teachers might ask students to engage in non–selfish perspective–building activities. To focus on our individual freedoms and responsibilities, teachers might utilize the edited poetry collection,

What Have You Lost?

(

Nye, 1999)

. The text includes over 130 poems for adolescent readers that address the issue of loss, focusing especially on the ways in which loss "startles us awake" and how "losing casts all kinds of shadows on what we thought we knew" (pp. xi–xii).

After reading and reflecting on several poems from the collection, teachers might ask students to draft their own poem in the attempt to answer the question, "What have you lost?" Upon sharing and discussing their work, members of the classroom community might then connect their personal expressions to the novel Feed by engaging in a small–group or whole–class discussion centered on the following:

- In what ways does loss manifest itself in the novel?

- How does this loss mirror or run counter to your own expression of loss?

- How is loss universal?

- How is loss shaped by external forces acting upon us (geographic, financial, social, etc.), thus making the experience unique? Can I know your loss?

- Is loss inevitable?

- How did you feel upon completion of the novel?

- Is there any hope in the novel? How is it manifested?

- Why might it be important to find hope in this title?

To leave students feeling empowered and optimistic after reading a difficult and emotionally draining title like Feed , teachers might ask students to consider an alternative to loss, that of hope. After providing students with watercolor paint sets and clean sheets of paper, teachers might pose the seemingly simple, but essentially important, question, "What does hope look like?"

To move students from an individual to collective understanding of the responsibilities we all possess, teachers might ask students to consider their role in the global landscape by hosting a Mock United Nations Summit. Students might work in small groups to research various topics of global concern (hunger, poverty, environmental exploitation, race and gender inequity, child labor, sex slavery, etc.). They might then apply their understandings to the education of others by facilitating a public roundtable discussion involving teachers, administrators, parents/guardians, and community members. Ideally, these conversations would expose attendees to the complexity of our global relationships and provide increased awareness of how our actions have far–reaching effects well beyond our homes, communities, and borders.

In the Here and Now: Contemporary Fiction

Many adolescent readers are drawn to fiction that is set in the present. They can often identify with characters and events in contemporary fiction, as they and their experiences are easily recognizable and somehow familiar, despite the differences of place or culture or values that underpin the story. Through 44 contemporary fiction, we witness models for our own lives and live vicariously through others, learning from their mistakes without necessarily having to make them on our own. The recognizable realities of contemporary novels offer readers "a better chance to be happy" by helping them develop "realistic expectations" and "know both the bad and the good about the society in which they live" ( Donelson &Nilsen, 2004 , p. 117).

Briefly Annotated Titles

Miguel, the protagonist in

We Were Here

(

de la Peña, 2009

), has been placed in a group home as a result of a tragic event involving his family. His counselor requires him to keep a journal to work through the related guilt and frustration he feels. While in the group home, Miguel meets Rondell, a special needs teen with violent tendencies, and Mong, a young man haunted by his past. Although they have just met and don't particularly like one another, the boys decide to break out of the home and set out along the California coast together. On their voyage, they encounter blatant racism, experience incredible scenes and acts of beauty, challenge their assumptions of one another and their growing friendships, and face the demons that sent them out on this quest for identity. Miguel, in particular, examines his understandings of family, culture, race, geography, guilt, and acceptance. This story of struggle, survival, guilt, anger, and redemption offers readers insight into the human condition, forging a connection that highlights the commonalities that exist in spite of difference.

In Sold (2006), McCormick gives voice to 13–yearold Laksmi, a Nepalese girl sold into child prostitution by her greedy stepfather. Laksmi finds herself trapped in a brothel in Calcutta, India, forced to endure terrifying and humiliating acts to assure her survival. Despite the brutality and seeming emptiness of her existence, Laksmi holds to hope; she draws strength from friendship, the written word, and determined resilience to stay true to herself at all costs. Readers will likely never endure the reality Laksmi suffers, but they can identify with the struggle to persevere in her courageous dedication to self–preservation.

Lucas ( Brooks, 2003 ) centers on Caitlin, a 15–yearold who lives with her somewhat distanced father and increasingly rebellious brother in an outwardly idyllic town on a small British island. From the moment she sees the mysterious Lucas wandering along the road, seemingly emerging from nowhere, she knows life will never be the same. Lucas, a free–spirited gypsy teen, speaks with candor and encourages Caitlin to reconsider her understandings of family, community, and self. Due to his outsider status, not everyone in town welcomes and accepts Lucas's presence. Community members blame him for a brutal attack on one of the island girls, and when vigilante justice prevails, Caitlin is forced to face the truth of Lucas's societal critique. Readers are left contemplating the role of the individual in society, the power of conformity, and the very definition of what it means to live.

Looking Deeper:

The Absolutely True Story of a Part–Time Indian

In his novel,

The Absolutely True Story of a Part–time Indian

(2007), Alexie

describes life on the Spokane Indian Reservation through the humorous and troubling story of 14–year–old Arnold "Junior" Spirit. Reflecting upon his experiences at his reservation school, he realizes, "My school and my tribe are so poor and sad that we have to study from the same dang books our parents studied from. That is absolutely the saddest thing in the world" (p. 31). He angrily throws the textbook in protest, breaks the nose of his teacher, and is suspended from school. In an effort to improve his prospects, Arnold decides to attend the high school in Reardon, a white farm town 22 miles away from the "Rez." This initiates his career as a "part–time Indian." On the Rez, he is Junior, the funny–looking kid everyone likes to beat up and a traitor who attends the privileged white school. At Reardon, he is Arnold, the only Indian —with the exception of the mascot.

Essential Questions

EQ: How can realistic fiction allow readers to explore questions of self–identity?

Arnold faces challenges familiar to many teens. His situations may be more extreme than those of many kids (Black–Eye–of–the–Month Club), and some may be specific to American Indians (loss of native land and language), but most adolescent readers can learn a great deal about facing adversity from Arnold, who makes good, though sometimes difficult, decisions and usually chooses to look at the bright side of onerous situations. Arnold's success stems in large part from his self–awareness. Throughout the diary, Arnold engages in introspection and trusts his feelings to guide him. Several instructional activities can encourage students to follow Arnold's lead and think about their own lives and decision–making processes.

Reflective journals or diaries foster intrapersonal awareness, or the cognitive ability to understand our own minds and selves ( Cappachione, 2008 ). Prompts such as the following could help readers better understand their personal identities:

- Who am I within my family? How do members of my family see me?

- Who am I within my social group? What roles do I assume in social situations? How do others view my social group?

- How did I become the person I am? What and/or who are the greatest influences?

- What dreams do I have? What challenges might I face as I pursue them?

- How are my experiences similar to or different from Arnold's? What can I learn from him?

- Do I agree with Arnold's claim that "life is a constant struggle between being an individual and being a member of a community" (p. 132)?

These written responses could scaffold study of the memoir or personal essay. A side–by–side examination of The Absolutely True Diary of a Part–Time Indian and Alexie's memoir–style personal essay, "Indian Education" (2005) , could help students explore the complex distinctions and overlaps that define truth and fiction. Students might then engage in an alternative (or complement) to the written memoir in the completion of a "Song of Myself" project. After reading Walt Whitman's poem, "Song of Myself" (2010), students create visual representations in response to the questions, "Who am I, and who do I want to become?" Containing words and images cut from magazines and newspapers, personal photographs, memorabilia, and drawings, collages depict how students perceive themselves in the past, present, and future. Extending the lesson to include PowerPoint presentations, Web pages, and other mixed media allows students to create contemporary texts of their own.

EQ: How can contemporary fiction allow for exploration of personal health and welfare of adolescents and adults in contemporary society?

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part–Time Indian

(

Alexie, 2007

) can help teachers and students learn about personal, social, and health–related issues such as substance abuse and eating disorders. According to the

National Institute on Drug Abuse (2009)

, in 2009, 20% of eighth graders reported using an illicit drug in their lifetime. Thirty–six percent of tenth graders and almost half of high school seniors reported using drugs at least once, while 30–35% had used them within the past year. Of high school students, 11% have been diagnosed with eating disorders, and one in five American women struggle with an eating disorder (

National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders, 2010

). Clearly, substance abuse and eating disorders are not unique to Native Americans. As Arnold wisely notes, "There are all kinds of addicts, I guess. We all have pain. And we all look for ways to make the pain go away" (p. 107). Arnold's maturity relative to these self–abusive habits is important for readers to consider.

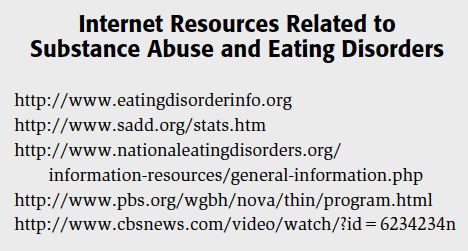

To help readers gain knowledge about these habits, teachers could set up inquiry stations containing Internet–connected computers (see sidebar, p. 00), a small library of informational texts, primary source documents, and personal narratives related to eating disorders and substance abuse. To create inquiry stations, English teachers might collaborate with health and science teachers, as well as school counselors and social workers who have specialized training in preventing self–destructive behaviors. As a follow–up or introduction to the inquiry project, teachers might draw, too, upon the expertise of the community— health department and law enforcement officials, psychologists, or health care professionals.

EQ: How might literature serve as a springboard for learning about different people and cultures?

There is no singular version of what it means to be a contemporary Native American. When Arnold's sister, Mary, marries a Flathead Indian and moves to another tribe's reservation in Montana, she writes to him about her new life. Non–Native American readers may be surprised to learn that there are major differences among tribes and tribal cultures. To help students learn more about the reservation Arnold describes, they might visit

http://www.spokanetribe.com/

. To extend student awareness of other Native communities, students might read more about the Nigigoonsiminikaaning (Red Gut) Reservation in Canada, a sovereign and alcohol–free nation (

http://www.nigigoonsiminikaaning.ca/languagecamp.php

). Students could explore both sites and attempt to understand the complexity of the similarities and differences between the Spokane and Nigigoonsiminikaaning communities. A field trip to a local museum could provide an active learning experience and allow teachers to draw upon the expertise of others (see National Museum of the American Indian at

http://www.nmai.si.edu

). Additionally, a speaker from a federally recognized Native American nation or tribe could provide students additional context regarding the beauty and difficulties of Arnold's life on and off the reservation.

EQ: Given the fact that contemporary fiction often explores issues of local and global concern, how might titles encourage readers to respond to social injustice that exists in our world today and spur productive action?

Alexie's novel has the potential to educate students about the realities of poverty and the relationship between privilege and power.

When Arnold arrives at his "white school" for the first time, he observes: "Reardon was the opposite of the rez. It was the opposite of my family. It was the opposite of me" (p. 56). To Arnold, the white kids in Reardon live a reality that is seemingly unavailable to him and his people. In consideration of this issue, students, working individually, in pairs, or in small teams, could explore the question, "Is the American Dream a myth, reality, or something else?" As photojournalists, they could create digital–photo persuasive essays that highlight inequity and social injustice in their and others' communities. Final projects could be shared with others in and out of the school by posting student discoveries on a class website.

When Arnold arrives at his "white school" for the first time, he observes: "Reardon was the opposite of the rez. It was the opposite of my family. It was the opposite of me" (p. 56). To Arnold, the white kids in Reardon live a reality that is seemingly unavailable to him and his people. In consideration of this issue, students, working individually, in pairs, or in small teams, could explore the question, "Is the American Dream a myth, reality, or something else?" As photojournalists, they could create digital–photo persuasive essays that highlight inequity and social injustice in their and others' communities. Final projects could be shared with others in and out of the school by posting student discoveries on a class website.

Tapping into Literature's Potential

Literature has the power to

- expose readers to new people, places, and ways of thinking;

- complicate existing understandings of the multiple communities in which we live;

- foster connections across history, culture, beliefs, and values.

As teachers who embrace this vision of literature, we believe that we miss the full potential of story when we fall prey to external demands that focus on oversimplification or the elimination of complexity for the sake of test performance. Young adult literature set in any time—past, future, or present—can be used strategically to support student acquisition of content knowledge and much more. By allowing students to grapple with the big questions of life and living, we help them gain the reflective awareness, critical stance, and global perspective necessary to contribute meaningfully as members of a twenty–first century democracy.

Wendy J. Glenn is an associate professor in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction in the Neag School of Education at the University of Connecticut where she teaches undergraduate and graduate courses in teaching literature, writing, and language. Dr. Glenn was named a University Teaching Fellow in 2009 and traveled to Norway as a Fulbright Scholar in 2009–2010. Her research centers on literature and literacies for young adults, particularly in the areas of sociocultural analyses and critical pedagogy. She is the author of Sarah Dessen: From Burritos to Box Office, Richard Peck: The Past Is Paramount (with Don Gallo), and Laurie Halse Anderson: Speaking in Tongues. She has published peer–reviewed articles in Research in the Teaching of English, English Education, The ALAN Review, English Journal, Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, Equity and Excellence in Education, SIGNAL, Teacher Education Quarterly, and Peremena/ Thinking Classroom. She is Past–President of the Assembly on Literature for Adolescents of the National Council of Teachers of English (ALAN).

Marshall A. George is a professor and Chair of the Division of Curriculum &Teaching in the Graduate School of Education at Fordham University in New York City. Formerly a member of the ALAN Board of Directors, Dr. Marshall is now the Chair of the Conference on English Education (CEE) and a member of the NCTE Executive Committee. His scholarship focusing on young adult literature has been published in The ALAN Review, English Education, Voices from the Middle, English Journal, SIGNAL, and Theory into Practice.

Academic References

Brooks, W. (2009). An author as a counter–storyteller: Applying critical race theory to a Coretta Scott King Award book. Children's Literature in Education , 40, 33–45.

Cappachione, L. (2008). T he creative journal for teens: Making friends with yourself (2nd ed.). Pompton Plains, NJ: Career Press.

Collier, C. (1987). Fact, fiction, and history: The role of the historian, writer, teacher, and reader. ALAN Review , 14, 5.

Delgado, R. (2000). Storytelling for oppositionists and others: A plea for narrative. In R. Delgado & J. Stefancic (Eds.), Critical race theory: The cutting edge (2nd ed., pp. 60–70). Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Donelson, K., & Nilsen, A. (2004). Literature for today's young adults (7th ed.). New York, NY: Allyn & Bacon.

Duncan–Andrade, J. M. R. (2007). Urban youth and the counternarrative of inequality. Transforming Anthropology , 15, 26–37.

George, M. A. (2001). What's the big idea? Integrating adolescent literature in the middle school. English Journal , 90(3), 74–81.

Glenn, W. J. (2005). History flows beneath the fiction: Two roads traveled in Redemption and A Northern Light . The ALAN Review, 32 , 52–58.

Jarolimek, J. (1990). Social studies in elementary education . New York, NY: Macmillan.

Johannessen, L. (2000). Using a simulation and literature to teach the Vietnam War. The Social Studies , 91, 79–83.

Lott, C., & Wasta, S. (1999). Adding voice and perspective: Children's and young adult literature of the Civil War. English Journal , 88(6), 56–61.

McLaren, P., & Giarelli, J. (Eds.). (1995). Critical theory and educational research . New York, NY: SUNY Press.

McNair, J. (2008). A comparative analysis of The Brownies' Book and contemporary African American children's literature written by Patricia C. McKissack. In W. Brooks & J. McNair (Eds.), Embracing, evaluating, and examining African American children's and young adult literature (pp. 3–29). Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press.

Pace, B. G., & Townsend, J. S. (1999). Gender roles: Listening to classroom talk about literary characters. English Journal , 88(3): 43–49.

Morrell, E. (2004). Becoming critical researchers: Literacy and empowerment for urban youth . New York, NY: Peter Lang.

National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders. Retrieved July 12, 2010, from http://www.anad.org/get–information/about–eating–disorders .

National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2009). Info facts. Retrieved July 12, 2010, from http://www.nida.nih.gov/pdf/infofacts/HSYouthTrends09.pdf Retrieved July 12.

Rice, L. (2006). What was it like? Teaching history and culture through young adult literature . New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Schreiner, D. (1924). The dawn of civilisation. In EDITOR? (Ed.), Stories, dreams, and allegories (pp. 00–00). London, UK: T. Fisher Unwin.

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. Understanding by design (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Prentice Hall.

Literary References

Alexie, S. (2007). The absolutely true diary of a part–time Indian . New York, NY: Little, Brown.

Alexie, S. (2005). Indian education. In The Lone Ranger and Tonto fistfight in heaven (pp. 171–180). New York, NY: Grove Press.

Anderson, L. H. (2008). Chains . New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Anderson, M. T. (2002). Feed . Cambridge, MA: Candlewick.

Bertagna, J. (2008). Exodus . New York, NY: Walker.

Brooks, K. (2003). Lucas . Somerset, UK: The Chicken House.

de la Péna, M. (2009). We were here . New York, NY: Delacorte.

Doctorow, C. (2008). Little brother. New York, NY: Tor.

Malley, G. (2007). The declaration . New York, NY: Bloomsbury.

McCormick, P. (2006). Sold . New York, NY: Hyperion.

Mikaelsen, B. (2004). Tree girl . New York, NY: HarperTempest.

Nye, N. S. (1999). What have you lost? New York, NY: Greenwillow.

Park, L S. (2001). A single shard . New York, NY: Clarion.

Whitman, W. (2010). Song of myself and other poems by Walt Whitman . New York, NY: Counterpoint.

Woodson, J. (2008). After Tupac and D Foster . New York, NY: Putnam.