ALAN v41n1 - Sports as an Entry Point to Literature

The Author's Connection

Sports as an Entry Point to Literature

I spent the majority of my teenage years obsessed with one thing: earning an athletic scholarship for basketball. It didn’t start out that way. Nobody in my family had ever been to college. Not my parents or my uncles or my aunts or cousins or anyone else in my family tree, as far back as I could trace it. But at the start of my sophomore year of high school, a savvy counselor got a hold of me.

“So, have you given any thought to college?” she asked.

“What do you mean by ‘college’?” was my response.

When she saw I wasn’t kidding, she shifted into a clever strategy. After high school, she explained, a lot of kids went to college to continue their education. But college was more than just academics. There were also athletic programs and study abroad opportunities and maybe I’d get lucky and meet the girl of my dreams. When she saw how that last part had piqued my interest, she pressed further. “Trust me, Matt. Go to college and you’ll meet pretty girls from all over the country. All over the world even.”

I left that meeting wondering— for the first time in my life—if college was a legitimate option for a mediocre student like me. But it wasn’t long before reality set in. Even if I got accepted, my parents would never be able to afford the tuition. And my grades certainly weren’t going to earn me any academic scholarships. The only other thing I could think of was basketball. If I worked hard enough at the game I loved, maybe it could be my ticket to college.

This epiphany marked a new phase in my life. I now had a tangible goal. I started spending all my free time in a gym shooting jumpers and running sprints and lifting weights. I went to the library every morning before school and read basketball magazines cover to cover. I kept out of trouble so I wouldn’t sabotage my future (and that’s how I’d started to think of myself—as someone who had a future). I was still a very average student, and I struggled through all the novels we were supposed to read in class, but my skills improved dramatically on the court, and by my senior year, several colleges had offered me a basketball scholarship. My dream of being the first in my family to go to college was coming true. I distinctly remember sitting at midcourt in an empty gym the day before I left home, trying to picture myself up at my new school, playing ball at the highest level and talking to all those pretty girls my counselor had described, girls from faraway places like Idaho and West Virginia and Delaware.

But a funny thing happened once I landed on campus. It was literature that I fell in love with.

Sure, I played ball. And there were certainly girls. But in the first English class I took my freshman year, a professor introduced me to a few “multicultural” authors that hit me right in the gut. I experienced books like The Color Purple and Drown and The House on Mango Street on such a visceral level—they gave me a secret place to “feel”—but the stories also woke up this intellectual part of my makeup I never even knew existed. Throughout the next four years, I read everything I could get my hands on, including many of the books I had dismissed in high school. I even started writing my own spoken word poetry—about growing up biracial and my working class neighborhood and the grace I sometimes experienced on a basketball court. My teammates thought I was crazy, of course. Why would a hoop player read poetry on the plane ride to Vegas for the Big West Tournament? I told myself I’d feel more at home once I got out of college and surrounded myself with fellow readers and writers.

By the time I got to graduate school, where I studied creative writing, I had morphed into a genuinely committed and successful student. Fiction had become my new obsession. I dreamed of one day writing a publishable novel of my own. However, I definitely didn’t feel at home in my MFA program the way I had imagined. In one of the first fiction classes I took, a girl glanced back at me and quietly asked her friend, “Since when did they start letting jocks into the program?” They both looked at me again with expressions of pure annoyance.

That was the day I decided sports and literary fiction simply didn’t mix. I had to either be a basketball guy or a writer. I couldn’t be both. So throughout the rest of my graduate school years, I distanced myself from my athletic past. I never once wrote about the game, never even mentioned it to any of my classmates. And when I graduated and moved up to Los Angeles to begin my life as an aspiring writer, I made one rule for myself: I would never, ever, write a novel about basketball. Why? Because the game didn’t define me. I was out to prove to everyone—okay, mostly myself—that I was more than just corner jumpers and that patented spin move in the lane. Why waste time writing about a silly game when I aspired to write about the world?

I made it three weeks before I started my first novel, Ball Don’t Lie .

For those who don’t know, Ball Don’t Lie follows a foster kid named Sticky who’s an amazing basketball player growing up on the streets of Venice Beach, California. In other words, I slipped up, broke my one rule. I failed. Except actually I didn’t. As the story came pouring out of me, I realized something. The story was set against a basketball backdrop but I was still writing about the world. What fascinated me about Sticky’s story wasn’t what he did on the hardwood, it was how he survived off of it. I spotlighted the crowd that frequented the gym, guys who assumed positions of power in this context. When it was game point, the best player on the court was the CEO, the president, the one percent—but as soon as the game ended, and he stepped back into the bright world that waited outside, all that power was immediately stripped away. Sticky was raised in this setting, among these powerful, powerless men. The novel was originally titled 3 Stones Back , a reference to Sticky’s low position within LA’s exaggerated social class structure. When my editor asked me to come up with a title that referenced basketball, I was devastated. It made me feel like I was still that ex-jock trying to fake his way into the literary club.

It took me years to get over myself enough to admit that my editor was right. The title Ball Don’t Lie is more inviting to certain high school readers. I recently met a student named Terrence, an all-state basketball player in South Carolina, who had read the book six times. It was his all-time favorite book, he announced excitedly. His teacher had given it to him in a reading class, and as soon as he read the title, he asked if he could check it out overnight. It was about basketball, the game he loved. But as he described in great detail all his favorite parts of the book, I realized not one of them had anything to do with basketball.

In a way, when I write novels that include sports, I’m employing the same strategy my counselor used to get me interested in college. The game motivates readers like Terrence to penetrate my fictional world, and once he’s inside with solid-enough footing, I’m able to take him to the places that any other ambitious work of art aims to take its audience.

As I wrote at the beginning of my review of Matthew Quick’s Boy 21 in the New York Times , there’s more to playin’ ball than just playin’ ball. If you’ve spent any time inside a gym or run fives at the local street-ball spot, you understand this. Most of what I know about the world was gleaned from inside a hoop gym populated by guys twice my age. But to the uninitiated, basketball is nothing more than what it looks like: a game. And books set against the backdrop of a game are often labeled like cans of soup and stuck on shelves reserved for “reluctant readers.” Novels with sports themes can certainly lure jocks into the library, but the best of them reach toward literature.

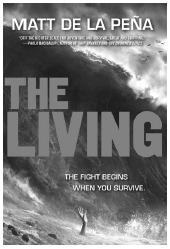

Matt de la Peña is the author of four critically acclaimed young adult novels— Ball Don’t Lie, Mexican White- Boy, We Were Here, and I Will Save You —and the award-winning picturebook A Nation’s Hope: The Story of Boxing Legend Joe Louis . In 2013, his fifth YA novel, The Living, will be released, along with his first middle grade novel, Curse of the Ancients . Matt received his MFA in creative writing from San Diego State University and his BA from the University of the Pacific, where he attended school on a full athletic scholarship for basketball. He currently lives in Brooklyn, New York, teaches creative writing, and visits high schools and colleges throughout the country.

Rick Chambers Is 2013 CEL Exemplary Leader

Rick Chambers is a former secondary school English teacher and department chair who, for more than 26 years, taught in several schools in Dufferin and Waterloo counties in Ontario, Canada, as well as with the Canadian Department of National Defence in Europe. In 1997, he joined the Ontario College of Teachers, the regulatory body for the teaching profession in Ontario, where he managed the Professional Learning Program and served as a program officer in the Accreditation Unit. Since 2004, he has worked for Agriteam Canada on a teacher professional development project in South Africa and for the United Church of Canada on a project to develop standards of practice, ethical standards, and discipline processes for ministry personnel. He has also served as a coordinator with the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE) at the University of Toronto in their Continuing Education Department.

Rick is past chair of the Conference on English Leadership (CEL) of NCTE, and has made presentations and contributed articles on English teaching, assessment, literacy education, and professional development nationally and internationally. Currently, he is part of a team at OISE writing an online teacher education course for teachers of English as a Foreign Language. He also continues to write and conduct courses for Pearson Professional Learning, a division of Pearson Education Canada. He is a coauthor of the Literacy in Action series of English language arts books for grades seven and eight. Rick is the Canadian consultant for the Stepping Out resource— professional development courses and materials focused on middle and secondary school cross-curricular writing, reading, and viewing. He has delivered courses on the Stepping Out resource in all parts of Canada.

Rick holds degrees from McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, and the University of Calgary in Alberta. He will be presented with this award during the CEL Annual Convention in Boston, Massachusetts, on Sunday, November 24, 2013, at the CEL Sunday Luncheon.