CTER v30n2 - Preservice Teachers' Motivation and Leadership Behaviors Related to Career Choice

Preservice Teachers’ Motivation and Leadership Behaviors Related to Career Choice

Breanne M. Harms

John Deere Company – Kansas CityNeil A. Knobloch

University of Illinois at Urbana-ChampaignAbstract

The purpose of this descriptive survey was to explore and describe why graduates who were certified to teach agriculture in secondary education chose teaching as a career. Twenty-nine student teachers from four universities in a Midwestern state participated in the study. There were several findings from the study. First, the researchers found that 24 out of 29 preservice teachers in the study planned to become teachers. Second, career choice was related to intrinsic and extrinsic career choice motives. Preservice teachers choosing formal education as a career had intrinsic motives. On the other hand, preservice teachers who anticipated careers in non-formal education had extrinsic career choice motivation. Third, preservice teachers who plan to pursue formal education careers were more efficacious than their peers who planned to pursue nonformal education careers or were undecided about their careers. Third, the preservice teachers identified as having transformational and transactional leadership behaviors and these leadership behaviors were not related to career choice.

Introduction and Theoretical Framework

Recruiting and retaining quality teachers is crucial to attaining excellence in education ( Darling-Hammond, 1999 ; McCampbell & Stewart, 1992 ). Preservice agricultural education teachers who possess the characteristics of being qualified, caring, and competent ( NCTAF, 1996 ) are likely to be sought after by non-profit and business organizations, which could also benefit from these characteristics. The teaching profession competes against other important professions for the most talented people ( McCampbell & Stewart, 1992 ), and changes that have occurred in agriculture in recent years have made it possible for qualified preservice agricultural education teachers to secure employment outside of the classroom at very competitive salaries ( Miller & Muller, 1993 ).

Graduates who are certified to teach in agricultural education are entering nonformal education careers. In 2001, only 59% of qualified preservice teachers in agricultural education entered the teaching profession. At the same time, 67 positions for agricultural education teachers remained unfilled nationwide ( Camp, Broyles, & Skelton, 2002 ). Furthermore, Craig (1984) found that, though the number of preservice teachers who completed degrees and were qualified to teach exceeded the need for classroom teachers, the number who chose careers outside of education ultimately led to the teacher shortage in the nation. Harper ( 2000a , 2000b ) conducted a needs assessment of future issues and concerns in agricultural education in Illinois. Stakeholders identified recruiting good people to teach and offering teacher salaries that are competitive with the rest of the agricultural industry were important needs. This study was conducted because understanding the influences of preservice teachers’ choices to teach or not to teach could help to more effectively recruit high-quality individuals and provide targeted strategies to help retain them in the teaching profession.

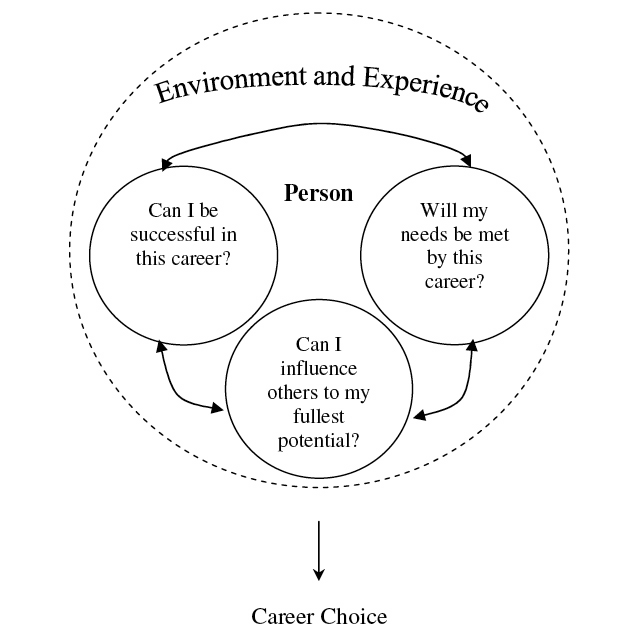

As college students complete internships and use past experiences in preparing to enter the workforce, many of them ask a variety of questions to help them choose the appropriate careers. The researchers inductively conceptualized career development to represent why preservice teachers in agricultural education would choose to teach in a formal classroom setting. Creative and thoughtful integration of theories in career psychology can stimulate theory building and enhance career development practice ( Chen, 2003 ). When choosing careers, people are faced with a series of questions. People are drawn to questions that are most important to them or upon which they place the most value or emphasis. Although there are many, three questions guided the researchers to help narrow the scope of the many possibilities for choosing a career: Can I be successful in this career? Will my needs and expectations be met by this career? Do I see myself influencing others to reach their fullest potential in this career? In addition to striving to answer these questions, often interdependently, people making decisions about their careers also gather information from their environment and make career decisions within the contexts in which they find themselves. The conceptual framework (Figure 1) was informed by a constructivist perspective of career development, primarily based the assumptions of social cognitive career theory ( Lent, Brown, & Hackett, 1996 ), and was grounded on three theories: Maslow’s (1954) needs theory, Bandura’s self-efficacy theory, and Bass’s (1985) transformational leadership theory. Each theory is briefly reviewed in the context of career choice for the theoretical framework. Furthermore, career choice is reviewed for people in general, for those in helping careers (e.g., nursing and teaching), and more specifically for those in career and technical education and agricultural education.

Needs Motivation: Will my needs and expectations be met by this career?

Maslow’s (1954) needs theory represented the question related to whether people’s needs would be met by choosing among their career alternatives. In his theory, Maslow suggested that people are motivated by a series of unmet needs, and that lower-level needs must be satisfied before higher-level needs (e.g., selfactualization) can be satisfied. Needs theory can potentially influence career choice in several different ways, both through anticipated job satisfaction and making career choices. Research in education has shown that needs theory relates to job satisfaction, as the absence of three higher-order needs (self-esteem, autonomy, and self-actualization) was shown to be a major contributor to low teacher satisfaction ( Carver & Sergiovanni, 1971 ; Frances & Lebras, 1982 ; Sweeney, 1981 ; Trusty & Sergiovanni, 1966 ; Wright, 1985 ). Additionally, although Maslow did not believe that a fulfilled need could serve as motivation, research has shown that satisfying self-actualization needs increases motivation ( Glassman, 1978 ; Heneman, Schwab, Fossum, & Dryer, 1980 ). Thus, as individuals have self-actualizing experiences during career preparation, they may be more motivated to enter the career field in which they had that experience. For example, if a preservice teacher had a selfactualizing experience during student teaching or in early field experiences, that individual may be more likely the pursue a career in the formal education field. Likewise, if a preservice teacher has a self-actualizing experience during an internship in agribusiness, that individual may more likely pursue a career in nonformal education. According to Wankat and Oreovicz (1993) , intrinsic motivation generally satisfies basic human needs, whereas extrinsic motivation may satisfy a higher-level need (i.e., people may equate salary with esteem). Tenably, those whose career decisions are shaped by intrinsic motives may be satisfied with different careers than those who have extrinsic career choice motives, as the two groups seek different things from potential careers. For the purpose of this study, needs theory was represented by individuals’ intrinsic and extrinsic career choice motives.

Teaching Self-Efficacy: Can I be successful in this career?

Bandura’s (1997) self-efficacy theory underpins career choice. Bandura’s theory relates to whether people believe they can be successful in their chosen careers and the number of career alternatives that they may consider. Bandura suggested that self-efficacy, or people’s beliefs in their own abilities to complete a specific task, influences performance, behavioral choices, and persistence. The influence of self-efficacy on performance is related to career choice in a number of ways. Self-efficacy complements skill sets in individuals seeking careers and may facilitate career attainment for those seeking careers in areas that align with their skill sets. However, because entering a profession is also based on the fit of skills to preferred careers, if individuals do not have the required skills for a position, even high self-efficacy beliefs may not allow them to perform well in that role ( Vroom, 1964 ). Lent, Hackett, and Brown (1996) further suggested that self-efficacy may facilitate career attainment in a given performance domain when paired with requisite skills.

As people perform better and as people’s belief in their self-efficacy grows, they consider more career options, show greater interest in their career options, perform better educationally in their career preparation, and have greater staying power in their chosen pursuits ( Bandura, 1997 ). People formed a sense of efficacy in a variety of job-related activities as they performed them at home, school or within the community ( Lent, Hackett, & Brown, 1996 ). The stronger students’ efficacy beliefs, the more interest they expressed in a given occupation ( Betz & Hackett, 1981 ; Branch & Lichtenberg, 1987 ) and the more career options they believed were possible ( Betz & Hackett, 1981 ; Lent, Brown, & Larkin, 1986 ). Interest in jobrelated tasks can be viewed as an extension of self-efficacy, because people often form an interest in an activity when they see themselves as competent in performing it and see it producing valued outcomes. People also developed a dislike for activities that they did not enjoy or anticipated negative or non-valued outcomes, and they often avoided attempting those activities ( Bandura, 1986 ; Lent, Larkin, & Brown, 1986 ). In the context of this study, highly efficacious preservice teachers should have a higher likelihood of entering a career in the area in which they are efficacious, whether it be in the classroom, Extension, or business/industry.

Transformational Leadership: Do I see myself influencing others?

Transformational leadership is a leadership behavior that motivates followers and leaders to do more than they thought possible by “(a) raising followers’ level of consciousness about the importance and value of specified and idealized goals, (b) getting followers to transcend their own self-interest for the sake of the team or organization, and (c) moving followers to address higher-level needs” ( Bass, 1985 , p. 20). Transformational leaders were concerned with the performance of followers and with developing followers to their fullest potential ( Avolio, 1999 ; Bass & Avolio, 1990 ). According to Bass and Avolio (1993) , people express their leadership behaviors on continuum of three domains: (a) transformational leadership; (b) transactional leadership; and, (e) nonleadership.

The transformational leadership domain is comprised of five factors: idealized influence (attributed), idealized influence (behavior), inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration. Leaders with Idealized Influence (attributed and behavior) display conviction; emphasize trust; take stands on difficult issues; present their most important values; and emphasize the importance of purpose, commitment, and the ethical consequences of decision. Idealized Influence (attributed) occurs when followers identify with and emulate those leaders who are trusted and seen as having an attainable mission and vision. Idealized influence (behavior) refers to leader behavior that results in followers identifying with leaders and wanting to emulate them ( Barnett, McCormick, & Connors, 1999 ; Bass & Avolio, 1995 ). Leaders with Inspirational Motivation articulate an appealing vision of the future, challenge followers with high standards, talk optimistically and with enthusiasm, and provide encouragement and meaning for what needs to be done. Leaders with Intellectual Stimulation question old assumptions, traditions, and beliefs; stimulate in others new perspectives and ways of doing things; and encourage the expression of ideas and reasons. Leaders with Individualized Consideration deal with others as individuals; consider their individual needs, abilities and aspirations; listen attentively; further their development; and advise and coach.

The transactional leadership domain is comprised of three factors: contingent reward, management-by-exception (active), and management-by-exception (passive). Contingent Reward leaders are leaders who: engage in a constructive path-goal transaction of reward for performance, clarify expectations, exchange promises and resources, arrange mutually satisfactory agreements, negotiate for resources, exchange assistance for effort, and provide commendations for successful follower performance. Management-by-Exception (active) leaders are leaders who: monitor followers’ performance and take corrective action if deviations from standards occur and enforce rules to avoid mistakes. Management-by-Exception (passive) leaders are leaders who fail to intervene until problems become serious and wait to take action until mistakes are brought to their attention. The nonleadership domain is comprised of one factor: laissez-faire. Laissez-faire leaders are leaders who avoid accepting responsibility, are absent when needed, fail to follow up requests for assistance, and resist expressing views on important issues ( Bass & Avolio, 1995 ).

The most direct tie that research in transformational leadership has to career choice is through the distinction between authentic and inauthentic transformational leadership. According to Bass and Steidlmeier (1999) , “the authentic [transformational leaders] are inwardly and outwardly concerned about the good that can be achieved for the group, organization, or society for which they feel responsible” (p. 188). Individuals who were authentic transformational leaders— those concerned for the common good—were altruistic in nature ( Howell & Avolio, 1992 ). Young (1995) found that some of teachers’ career choice reasons were altruistic in nature. Therefore, if authentic transformational leaders are altruistic, and individuals tend to enter teaching careers for altruistic reasons, the altruistic nature of teaching may positively influence transformational leaders’ career choices, leading transformational leaders into formal education careers. Researchers in CTE have stated that leadership development is an important and long-standing concern in CTE, as indicated from their commitment to leadership development in the students involved in the related student organizations ( Wonacott, 2001 ), including the National FFA Organization. In the last 15 years, leadership development in CTE has moved away from task-oriented behaviors toward a model of transformational leadership to point CTE in new directions ( Moss & Liang, 1990 ). The National Center for Research in Vocational Education conceptualized leadership development as:

…improving those attributes—characteristics, knowledge, skills, and values—that predispose individuals to perceive opportunities to behave as leader, to grasp those opportunities, and to succeed in influencing group behaviors in a wide variety of situations. Success as a leader in vocational education is conceived primarily as facilitating the group process and empowering group members ( Moss, Leske, Jensrud, & Berkas, 1994 , p. 26).Additionally, beyond CTE but still related to agricultural education, research in Extension has shown that transformational leadership behaviors had a consistently positive correlation with organizational outcomes such as organization effectiveness and job satisfaction (Brown, 1996).

Though not appearing in agricultural education or CTE studies and not related to career choice, additional research that has been done is also related to this study, as it lends additional weight to the researchers’ belief that career and technical education teachers that demonstrate transformational leadership behaviors will meet with greater success. Much of the research on transformational leadership that has been done in schools has focused on the positive effects that school personnel’s transformational leadership behaviors had on the students and school culture ( Leithwood & Jantzi, 1997 ; Leithwood, 1994 ; Silins, 1994 ). Furthermore, research has shown that a positive school culture was associated with increased student motivation and achievement, improved teacher collaboration, and improved attitudes among teachers toward their jobs ( Sashkin & Sashkin, 1990 ; Sashkin & Wahlberg, 1993 ; Ogawa & Bossert, 1995 ). Therefore, teachers that are transformational leaders may also influence students through improving school culture and enjoy higher levels of job satisfaction.

Career Choice in Career, Technical, & Agricultural Education

Career development starts early in a person’s life and is shaped by personal and environmental factors ( Bandura, 1986 ; Betz & Hackett, 1981 ). Personal and social experiences influence helping professionals’ career choices. Professionals in the helping professions often choose careers based upon childhood experiences, personal and professional goals, beliefs and values, and being inspired by family and peers to serve others ( Fischman et al., 2001 ). Further, the presence of teachers in the family was a significant factor influencing teacher candidates’ decisions to teach ( Marso & Pigge, 1994 ).

Personality plays a role in the careers people choose. Holland (1973) suggests that people fall into one of six personality types: realistic, investigative, artistic, social, enterprising, or conventional. People tend to seek careers where they can be around others that are similar to themselves, creating a positive work environment and experience. Holland posited that people who are in work environments with others like themselves will be more satisfied and successful. Holland’s (1973) career choice theory has been shown to apply to populations of elementary teachers ( Walsh & Huston , 1988). Because of this, Young (1995) suggested that the teaching profession may attract individuals who consider the job a good “fit” for them and who want to make a contribution to society and work with young people. Perhaps some feel that this “fit” is a calling to serve in the career. Additionally, Ginzberg (1988) suggested that career choice is a three-stage process that begins at childhood and develops through teenage years. During the final stage, realistic (age 17 through young adulthood), people familiarize themselves with alternatives and eventually develop a compromise that allows them to use their talents and interests while as many of their goals and values as possible will be satisfied. Perhaps some considering careers will be drawn to a greater extent by intrinsic or altruistic motives, while others may be pulled toward other careers due to extrinsic motives depending upon the motives and values of those making the career choices.

Various factors explain career choice for people in general, for those in helping careers, and more specifically for those in career and technical education and agricultural education. Some of the research that has helped to identify these influential factors has been focused specifically on determining the influences on career choice, while other research has determined the factors through gathering data on what causes individuals to remain in and/or leave careers. The researchers summarized the review of literature into six factors—both intrinsic or extrinsic motives—that influenced career choice of preservice teachers. Three of these items, (a) serving others, (b) touching people’s lives/making an impact, and (c) “calling” to a career, measured intrinsic career choice motivation, while the remaining three, (d) salary and benefits, (e) balance between career and personal time, and (f) opportunities for advancement/personal growth, measured extrinsic career choice motivation.

People are likely attracted to teaching because of a combination of altruistic, intrinsic, and extrinsic motives ( Seng Yong, 1995 ). Bergsma and Chu (1981) stated that people do not enter teaching to satisfy needs, but rather to help young people and to help the education system. Studies on prospective and practicing teachers actually revealed that the two main altruistic reasons for choosing teaching were the desire to work with young people (Brown, 1992; Chandler, Powell, & Hazard, 1971; Fox, 1961 ; Joseph & Green, 1986 ; Serow, Eaker & Ciechalski, 1992 ; Thom, 1992 ) and the desire to contribute to society (Brown, 1992; Chandler et al., 1971; Freidus, 1992 ; Goodlad, 1984 ; Joseph & Green, 1986 ; Richardson, 1988 ; Toppin & Levine, 1992 ). Research in other helping careers has indicated that people enter those careers for similar reasons. It has been shown that altruism, a desire to help others, or intrinsic motivation are factors that strongly explained a portion of the decisions of those choosing to enter a career in nursing ( Fagermoen, 1997 ; Good, 1993 ; Parker & Merrylees, 2002 ; Wicker 1995 ).

While intrinsic factors influence some to enter helping careers, extrinsic factors have been shown to influence teachers’ decisions to leave the teaching profession. A market-responsive model has been used to explain why people choose careers. This model suggests that individuals make career choices based on demand and the level of compensation ( Ochsner & Solmon, 1979 ). This model predicts that students prepare for an occupation that will be in high demand and will maximize their earnings. Though a much more extrinsically-focused model, the research in teaching has supported its suggestion, as well. Han (1994) found that teachers’ salaries relative to alternative occupations pursued by college graduates had an effect on career choices of prospective and current teachers. In addition to investigating reasons for entering a career, some of the research reviewed related to reasons for leaving careers, as well. These include maintaining a balance between career and personal time ( Fischman, Schutte, Solomon & Wu Lam, 2001 ), salary and opportunity for advancement ( Litt & Turk, 1985 ), lack of support from the principal ( Ladwig, 1994 ), problems with student discipline, lack of student motivation, and lack of respect from community, parents, administrators, and students ( Marlow, Inmar, & Betancourt-Smith, 1996 ). Research in another helping field, Extension education, has shown that a portion of agent attrition in that field is also related to pay, excessive time requirements, and too many requirements for advancement ( Rousan & Henderson, 1996 )—reasons which are extrinsic.

More specifically, research in agricultural education and CTE supports the results of the research in general helping careers. Those who choose careers in agricultural education often do so due to altruistic or intrinsic motives, as evidenced by what attracted them to the profession, their reasons for remaining in the profession ( Pucel, 1990 ; Ruhland, 2001 ), or what they most enjoy about the profession ( Wright & Custer, 1998 ). On the other hand, of those who leave, many attribute the decision to extrinsic motives ( Pucel, 1990 ), including salary, little opportunity for advancement, and an inadequate balance of career and personal time ( Knight, 1977 ). Several researchers have looked at various factors regarding career choice, satisfaction, and retention in agricultural education and CTE include: stress ( Ruhland, 2001 ; Pucel, 1990 ), quality of first teaching experiences ( Grady, 1990 ), academic ability ( McCoy & Mortensen, 1983 ; Miller & Muller, 1993 ; Wardlow, 1986 ), teacher self-efficacy ( Knobloch & Whittington, 2002 ), student morale ( Moss & Briers, 1982 ), and adequacy of teacher preparation (Cole, 1984; Miller & Muller, 1993 ).

Career choice among individuals, those in helping careers and in agricultural education and career and technical education, is shaped by many influences. The relationships between needs theory and self-efficacy theory relating to career choice and satisfaction have been studied much more than transformational leadership. Research in helping careers and in agricultural education and CTE clearly indicates that people who enter those careers are often driven by intrinsic motives (representing needs theory for this study), while those who leave sometimes do so for extrinsic reasons. Self-efficacy influences commitment to and performance in careers, and it also influences the career options that individuals may consider as they begin their career search. Although no studies in agricultural education and CTE were found to have investigated transformational leadership and career choice, transformational leadership theory suggests that those who are transformational leaders may be more altruistic in nature and therefore, perhaps they will be more inclined to enter formal education—teaching in the school classroom setting.

Purpose and Objectives

The purpose of the study was to explore and describe why graduates who were certified to teach agriculture in secondary education chose teaching as a career. The objectives of the study were to: (a) identify anticipated career choices for preservice agricultural education teachers after their student teaching internships, (b) describe differences in preservice teachers’ motives, self-efficacy, and leadership behaviors based on their career choices, and (c) describe the relationships of motives, selfefficacy, and leadership behaviors with career choice.

Methods and Procedures

This was an exploratory descriptive survey. The target population was a census of all preservice teachers who completed their student teaching internship in agricultural education in a Midwestern state during the spring semester of 2003. Twenty-nine out of 30 preservice agricultural education teachers from four universities responded to the mailed questionnaire, yielding a 97% response rate. Demographically, 52% were women, 72% were enrolled in high school agricultural education classes for at least one year, and 66% were enrolled in four years of high school agricultural education. Sixty-nine percent of the participants were members of the National FFA Organization for at least one year during high school, 58% served as chapter officers, and 10% served as either minor (section president) or major (state president, vice-president, reporter, secretary, or treasurer) state officers. All participants who were FFA members (N = 20) served as at least a chapter officer. Finally, 69% of the respondents fulfilled one or more leadership roles in college organizations.

The data were collected through a survey questionnaire using Dillman’s (2000) tailored design method within one month of the conclusion of the student teaching experience. The items that measured variables for this study were part of a larger instrument comprised of 105 items. The items for this study consisted of 48 of those items, measuring five variables and six characteristics. The study had five independent variables: (a) intrinsic and extrinsic motives, (b) teacher efficacy, (c) transformational leadership behaviors, (d) transactional leadership behaviors, and (e) nonleadership behaviors. The dependent variable of the study was expectancy of entering the teaching profession and was measured through the use of one openended question that asked the participants, “At this point in time, what is your career choice?”

The independent variable of intrinsic and extrinsic motives was measured by an instrument developed by the researchers based on career choice and longevity literature. The six-item instrument asked participants to rank-order six items that influence career choice, from (1) most important to (6) least important. Three of these items, (a) serving others, (b) touching people’s lives/making an impact, and (c) “calling” to a career, measured intrinsic career choice motivation, while the remaining three, (d) salary and benefits, (e) balance between career and personal time, and (f) opportunities for advancement/personal growth, measured extrinsic career choice motivation. The three items that measured intrinsic career choice motivation were summed to represent the type of career choice motivation of participants. The rank-order sum of the three intrinsic items ranged from 6 to 15. Participants’ sums that were in the 6 to 10 range were identified as having an intrinsic motivation. Participants’ sums that were in the 11-15 range were identified as having an extrinsic motivation (Table 1).

Teachers’ sense of efficacy was measured using 24 items from the Teacher Efficacy Scale ( Tschannen-Moran & Woolfolk Hoy, 2001 ) and 7 items developed from Dare and Leach’s (1999) study. The items were measured using Bandura’s (1997) 9-point efficacy scale with anchors at: (1) nothing; (3) very little; (5) some influence; (7) quite a bit; and (9) a great deal. The reliability of the TES instrument has ranged from 0.92 to 0.95 ( Tschannen-Moran & Woolfolk Hoy, 2001 ).

The Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ), written by Bass and Avolio (1995) , was used to measure three leadership behaviors: (a) transformational leadership (20 items); (b) transactional leadership (12 items); and, nonleadership (4 items). The instrument used a 5-point scale with anchors at (0) not at all, (1) once in a while, (2) sometimes, (3) fairly often, and (4) frequently, if not always. The developer of the instrument tested the reliability of the instrument with nine samples (n = 2,154) composed of others evaluating a target leader, and reliabilities for the total items and each leadership factor scale ranged from 0.74 to 0.94 ( Bass & Avolio, 2000 ). Although the MLQ had content and construct validity, a panel of experts in agricultural education reviewed the existing instrument to establish content validity in agricultural education.

A field test was also conducted to establish face validity and reliability of the instrument in agricultural education. The instrument was field tested with seven graduate students in agricultural education, three of whom had previously completed their student teaching internships. Changes were made to reflect the feedback provided by the field testers. The instrument was pilot tested with 15 preservice agricultural education teachers who completed their early field experience and were enrolled in a teacher education seminar. Additionally, three graduate students in agricultural education that had already completed their student teaching internships were part of the pilot test. The internal consistency was tested using Cronbach’s (1951) alpha. The estimate of reliability using Cronbach’s alpha was 0.65 for the 36- items from the MLQ that represented the chosen variables.

The researchers analyzed the data using the Statistical Package for the Social Science, Personal Computer version (SPSS/PC+). Participants whose responses were incomplete were automatically excluded in the data analysis procedures. Depending on the level of measurement of the variable, appropriate descriptive statistics—frequencies, percentages, population means, and population standard deviations—were used to describe the accessible population. Population means, population standard deviations, and effect sizes were rounded to the nearest 1/100th. Frequencies were rounded to the nearest whole number. For objective one, the researchers coded the open-ended question of, “At this point in time, what is your career choice?” by grouping responses into one of three response categories: (0) formal education careers, (1) non-formal education careers, and (2) undecided. The researchers then reported frequencies for each of the career choices. For objective three, the researchers averaged the scores for intrinsic motives, extrinsic motives, teachers’ sense of efficacy, and each of the three leadership behavior domains. The researchers determined a priori that a mean of 2.50 or greater indicated that a participant identified himself or herself as exhibiting that leadership behavior. Effect sizes were calculated to determine the difference in motives, self-efficacy, and leadership behaviors between those choosing formal education careers and those choosing non-formal education careers. Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s (1988) d. Cohen’s descriptors were used to interpret the effect sizes: (a) small effect size: d = .20; (b) medium effect size: d = .50; and, (c) large effect size: d = .80. For objective 3, the researchers used Eta2 (η2) to determine the measure of association between the rank-order of the intrinsic and extrinsic motives and career choice, and measure of associations between self-efficacy, leadership behaviors and career choice. Relationships were described using Davis (1971) conventions: (a) very strong association: η = .70, (b) substantial association: η = .50, (c) moderate association: η = .30, (d) low association: η = .10, and (e) negligible association: η = .01. Effect sizes were interpreted using Cohen’s (1988) descriptors: (a) small effect size: η2 = .01; (b) medium effect size: η2 = .09; and, (c) large effect size: η2 = .25. Medium effect sizes were used as the decision criterion for relationships.

Findings

Regarding career choice, 83% (N = 24) indicated in their responses that, at the end of their student teacher experience, their anticipated career choice was formal education (e.g., high school agriculture teacher). Additionally, 10% (N = 3) indicated their anticipated career choice was non-formal education (e.g., agribusiness salesperson, youth development educator) and 7% (N = 2) were undecided. Regarding career motives, 42% (N = 10) of the preservice agricultural education teachers whose anticipated career choice was formal education ranked the three extrinsic motives highest among the six career choice motives provided (Table 1). These 10 preservice teachers had the lowest possible rankings for intrinsic motives (i.e., 1, 2, or 3). Eighty percent of the formal education preservice teachers based their career choice on intrinsic motives. Of those who chose non-formal education, two of the three preservice teachers based their career choice on extrinsic motives. The two preservice teachers who were undecided in their anticipated careers were split between intrinsic and extrinsic motives.

The groups were compared on their mean rankings of motives. Preservice teachers who planned to pursue a formal education career had an average mean ranking of 7.82 (SD = 2.06) for intrinsic motives and 13.18 (SD = 2.06) for extrinsic motives. Preservice teachers who planned to pursue a nonformal education career had an average mean ranking of 12.00 (SD = .00) for intrinsic motives, and 9.00 (SD = .00) for extrinsic motives. The two preservice teachers who were undecided regarding their career had an average mean ranking of 9.67 (SD = 4.04) for intrinsic motives, and 11.33 (SD = 4.04) for extrinsic motives. Preservice teachers planning to pursue formal education careers based their decision on intrinsic motives compared to their peers. Preservice teachers who planned to pursue nonformal education careers based their decision on extrinsic motives compared to those who were undecided. Preservice teachers who were undecided on their career plans identified with both intrinsic and extrinsic motives. There was a substantial association between intrinsic motives and career choice ( = .56) and a moderate association between extrinsic motives and career choice ( = .41). These associations had a large and medium effect sizes, respectively.

Table 1

Frequencies of Rankings of Motives by Career Choice (N = 29) Career Choice Intrinsic Motives

(Rank-order sum)Extrinsic Motives

(Rank-order sum)6 7 9 10 11 12 14 15 Formal Education (N = 24) 10 4 5 1 1 2 0 1 Non-Formal Education (N = 3) 1 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 Undecided (N = 2) 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 Note . The minimum score possible by summing the rank-orders of intrinsic motivation items is 6.00 and the maximum possible is 15.00. The dashed line indicates the median of all possible scores.

Preservice teachers’ sense of efficacy was 5.76 (SD = 1.35) for those who planned to pursue a teaching career in formal education, 4.93 (SD = .00) for those who planned to pursue a career in nonformal education, and 4.25 (SD = .21) for those who were undecided. Preservice teachers who planned to pursue a formal education career were more efficacious than their peers who were undecided ( d = 1.14, large effect size) or planned to pursue a nonformal education career ( d = .63, medium effect size). Preservice teachers who planned to pursue a nonformal education career were more efficacious than their peers who were undecided about their careers ( d = 4.58, large effect size). There was a moderate negative association ( η = .382) between teachers’ sense of efficacy and career choice. This relationship had a medium effect size.

Table 2

Descriptive Data for Motives and Teachers’ Sense of Efficacy by Career Choices Career Choice Formal Education

( N = 24)Non-Formal Education ( N = 1) Undecided ( N = 3) Intrinsic Motives a 7.82 (2.06) 12.00 (.00) 9.67 (4.04) Extrinsic Motives a 13.18 (2.06) 9.00 (.00) 11.33 (4.04) Teaching Self-Efficacy b 5.76 (1.35) 4.93 (.00) 4.25 (.21) Note . a Range of summed rank-orders, (1) most important to (6) least important, was 6.00 - 15.00 for intrinsic motivation items. b Scale: (1) Nothing; (3) Very little; (5) Some influence; (7) Quite a bit; (9) A great deal.

Regarding leadership behaviors, all three groups of preservice teachers identified themselves as exhibiting transformational leadership behaviors fairly often , transactional leadership sometimes , and exhibit transactional leadership behaviors and they exhibit nonleadership behaviors once in a while (Table 3). There were some group differences on leadership behaviors. Preservice teachers planning to pursue non-formal education careers identified having higher transactional leadership behaviors than their peers who planned careers in formal education ( d = .65, medium effect size) or were undecided ( d = 1.34, large effect size). Preservice teachers who were undecided about their career identified having fewer transformational and transactional leadership behaviors than their peers who planned to pursue formal ( d = .62, medium effect size for transformational leadership behaviors; d = .61, medium effect size for transactional leadership behaviors) or nonformal education careers ( d = 1.36, medium effect size for transformational leadership behaviors; d = 1.34, large effect size for transactional leadership behaviors as previously noted). There were no differences in nonleadership behaviors among the preservice teachers regardless of their career choices. There were low associations between transformational leadership and career choice ( η = .19), and transactional leadership and career choice ( η = .26). These associations had small effect sizes. There was a negligible association between nonleadership and career choice ( η = .06) with no effect size.

Table 3

Descriptive Data for Leadership Behaviors between Career Choices Career Choice Transformational Leadership Transactional Leadership Nonleadership Formal Education ( N = 24) 3.26 (.38) 1.99 (.40) .90 (.48) Non-Formal Education ( N = 2) 3.35 (.28) 2.25 (.47) 1.00 (.35) Undecided ( N = 2) 3.03 (.18) 1.75 (.24) .88 (.53) Note . Scale: (0) Notat all, (1) Once in a while, (2) Sometimes, (3) Fairly often, and (4) Frequently, if not always.

Discussion and Implications

The researchers found that 24 of the 29 participating preservice teachers planned to become teachers. This was higher (83%) than the overall average placement rate of 59% and 73% who probably wanted to teach ( Camp et al., 2002 ), which suggests that these preservice teachers were motivated and had positive student teaching experiences. However, the small, one-shot nature of this study limits the generalizability of this finding. Overall, the findings should not be generalized beyond this small census study. This study should be replicated and conducted on a larger scale to strengthen the generalizability of the findings. By having a larger sample, structural equation modeling should be used to determine causal relationships between variables and career choice. Teacher educators should seek to understand factors (e.g., student teaching experience and relationship with the cooperating teacher) that influence preservice teachers’ career choices. According to Grady (1990) , positive first-year teaching experiences lead to higher retention. Further study on student teachers’ self-actualizing experiences may serve as motivation for preservice teachers to enter the career in which the experience happened ( Heneman, Schwab, Fossum, & Dryer, 1980 ).

Career choice was related to intrinsic and extrinsic career choice motives. Preservice teachers choosing formal education as a career had intrinsic motives. On the other hand, the preservice teachers that planned to pursue careers in non-formal education had extrinsic career choice motivation. This conclusion corroborated with the literature, in that those in helping careers tend to choose those careers for altruistic reasons ( Bergsma & Chu, 1981 ; Eick, 2002 ; Fagermoen, 1997 ; Good, 1993 ; Jantzen, 1981 ; Parker & Merrylees, 2002 ; Seng Yong, 1995 ; Wicker 1995 ). This also supported the literature in career and technical education indicating the same finding ( Pucel, 1990 ; Ruhland, 2001 ; Wright & Custer, 1998 ). Because of the differences in motives, teaching self-efficacy, and leadership behaviors of the preservice teachers, this suggests that individuals are attracted to the teaching profession if they consider the job a good fit for them ( Young, 1995 ). Although the skill sets are similar, the nature and culture of work in formal education is different than non-formal education or business and industry. Recruitment efforts for future teachers should be based on intrinsic motivation. Recruiters should advise potential agricultural education teachers (i.e., those that are interested in the intrinsic benefits) based on intrinsic motives as students make decisions about their college major.

Preservice teachers’ sense of efficacy was related to career choice. Preservice teachers who plan to pursue formal education careers had a higher sense of teaching self-efficacy than their peers who planned to pursue nonformal education careers or were undecided about their careers. This conclusion supported studies that found students had more interest in a given career when they had stronger self-efficacy beliefs ( Betz & Hackett, 1981 ; Branch & Lichtenberg, 1987 ). This finding suggests that preservice teachers identify more closely with classroom teaching competencies than their peers who plan to pursue nonformal education careers. Although teaching responsibilities are a component of a non-formal educator’s job responsibilities, the overall responsibilities also include administrative leadership, personnel and volunteer management, and program management ( Boyd, 2004 ; Cooper & Graham, 2001 ). This could be the reason why participants planning to pursue non-formal education careers reported higher leadership behaviors. Due to the broader scope of job responsibilities in agricultural education, a self-efficacy instrument should be created that includes administrative leadership and personnel and program management. This would help preservice teachers assess their self-efficacy regarding the different skill sets utilized in agricultural education. Faculty should continue to help college students in agricultural education develop a sense of efficacy, and further research should be conducted to understand how a teacher’s sense of efficacy influences career choice.

Leadership behaviors of the participating preservice teachers were not shown to be related to career choice. This conclusion was not congruent with the literature regarding transformational leadership behaviors in education because of the homogeneity of participants’ self-reported leadership behaviors. Transformational leadership has become increasingly important in career and technical education ( Wonacott, 2001 ), and leadership is also important in agricultural education ( Buriak & Shinn, 1993 ; Hughes & Barrick, 1993 ). Transformational leadership behaviors do make a difference in the teaching profession because they positively influence school culture ( Leithwood & Jantzi, 1997 ; Silins, 1994 ) and in turn, student achievement ( Sashkin & Wahlberg, 1993 ; Ogawa & Bossert, 1995 ). Because all participants identified themselves as exhibiting transformational leadership behaviors, there was no variability, thus implying no relationship exists between transformational leadership and career choice. The small sample and agricultural education’s mission being focused on leadership development could have contributed to the homogeneity of responses. Nearly 70% of the preservice teachers were involved in leadership development as FFA members in high school and served in leadership roles in college organizations. Self-reported measures can be influenced by the halo effect.

This occurs if participants respond in a socially desirable way and inflate certain aspects about their behaviors ( Kuh, 2001 ). Multiple methods such as peer ratings and personal interviews should be conducted to develop a better understanding how leadership behaviors might influence career choice. Further investigation should explore why preservice teachers who planned to pursue careers in non-formal education reported higher transactional leadership behaviors, and why preservice teachers who were undecided about their careers reported fewer leadership behaviors than their more decisive peers.

Two motivational theories, needs and self-efficacy, were related to career choice of preservice teachers in agricultural education. This is an important finding that should help CTE researchers explore factors that shape the choices preservice teachers make to become classroom teachers. This exploratory descriptive study was limited in its size and the positivist nature of studying leadership. Further investigation of leadership behaviors in the context of career development should be continued. One cannot easily deny the important role that life experiences, personality, and leadership play in the development of career and technical teachers. Mixed methods and naturalistic studies should be conducted to understand the role these factors play in career choice and development of career and technical education teachers.

Reference

Avolio, B. J. (1999). Full leadership development: Building the vital forces in organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W. H. Freeman.

Barnett, K., McCormick, J., & Conners, R. (1999). Transformational leadership in schools: Panacea, placebo, or problem? Journal of Educational Administration, 39 (1), 24-46.

Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. New York: Free Press.

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1990). The implications of transactional and transformational leadership for the individual, team, and organizational development. Research in Organizational Change and Development, 4, 231-272.

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1993). Transformational leadership: A response to critiques. In: Leadership theory and research perspectives and directions (pp. 49-80). New York: Academic Press

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1995). Multifactor leadership questionnaire (MLQ) web permission set . Redwood City, CA: Mind Garden.

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (2000). MLQ multifactor leadership questionnaire second edition sampler set . Redwood City, CA: Mind Garden.

Bass, B. M., & Steidlmeier, P. (1999). Ethics, character, and authentic transformational leadership behavior. The Leadership Quarterly, 10, 181- 217.

Bergsma, H. & Chu, L. (1981). What motivates introductory and senior education students to become teachers . Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Los Angeles.

Betz, N. E., & Hackett, G. (1981). The relationship of career-related self-efficacy expectations to perceived career options in college women and men. Journal of Counseling Psychology , 28, 399-410.

Boyd, B. (2004). Extension agents as administrators of volunteers: Competencies needed for the future. Journal of Extension, 42 (2). Retrieved October 25, 2005 from: http://www.joe.org/joe/2004april/a4.shtml

Branch, L. E., & Lichtenberg, J. W. (1987). Self-efficacy and career choice . Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, New York.

Brown, M. M. (1992). Caribbean first-year teachers’ reasons for choosing teaching as a career. Journal of Education for Teaching, 18(2), 185-195.

Brown, W. (1996). Leading without authority: An examination of the impact of transformational leadership on cooperative extension work groups and teams. Journal of Extension, 34 (5). Retrieved June 4, 2003, from http://www.joe.org/joe/1996october/a3.html

Buriak, P., & Shinn, G. C. (1993). Structuring research for agricultural education: A national Delphi involving internal experts. Journal of Agricultural Education, 34 (2), 31-36.

Camp, W. G., Broyles, T., & Skelton, N. S. (2002). A national study of the supply and demand for teachers of agricultural education in 1999-2001. Blacksburg, VA: Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Agricultural and Extension Education.

Carver, F. D., & Sergiovanni, T. J. (1971). Complexity, adaptability, and job satisfaction in high schools: An axiomatic theory applied. Journal of Educational Administration, 9 (1), 10-31.

Chandler, B. J., Powel, D., & Hazard, W. R. (1971). Education and the New Teacher . New York: Dodd Mead.

Chen, C. P. (2003). Integrating perspectives in career development theory and development. Career Development Quarterly, 51 , 203-216.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cooper, A. W., & Graham, D. L. (2001). Competencies needed to be successful county agents and county supervisors. Journal of Extension, 39 (1). Retrieved October 25, 2005 from: http://www.joe.org/joe/2001february/rb3.html

Craig, D. G. (1984). A national study of the supply and demand for teachers of vocational agriculture in 1984. Knoxville, TN: The University of Tennessee, College of Education.

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of test. Psychometrika, 31, 93-96.

Darling-Hammond, L. (1999). Teaching quality and student achievement: A review of state policy evidence . New York: National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future.

Dare, D. E., & Leach, J. A. (1999). Preparing tomorrow’s HRD professionals: Perceived relevance of the 1989 competency model. Journal of Vocational and Technical Education Research, 15 (2). Retrieved February 10, 2003 from: http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/ejournals/JVTE/v15n2/dare.html

Davis, J. A. (1971). Elementary survey analysis . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice- Hall.

Dillman, D. A. (2000). Mail and internet surveys: The tailored design method. New York: Wiley and Sons.

Eick, C. J. (2002). Study career science teachers’ personal histories: A methodology for understanding intrinsic reasons for career choice and retention. Research in Science Education, 32 , 353-372.

Fagermoen, M. S. (1997). Professional identity: Values embedded in meaningful nursing practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 25(3), 434-441.

Fischman, W., Schutte, D. A., Solomon, B., & Wu Lam, G. (2001). The development of an enduring commitment to service work. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 93 , 33-44.

Fox, R. B. (1961). Factors influencing the career choice of prospective teachers. Journal of Teacher Education, 7 (4), 427-432.

Frances, R., & Lebras, C. (1982). The prediction of job satisfaction. International Review of Applied Psychology , 31, 391-410.

Freidus, H. (1992). Men in a woman’s world: A study of male second career teachers in elementary schools. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Francisco.

Ginzberg, E. (1988). Toward a theory of occupational choice. Career Development Quarterly, 35 , 358-363.

Glassman, A. M. (1978). The challenge of management. New York: Wiley and Hamilton Publishing Co.

Good, J. D. (1993). Preservice teachers’ motivations for choosing teaching as a career (Doctoral dissertation, The Ohio State University, 1993). Dissertation Abstracts International, 54, 1763A.

Grady, T. (1990). Career mobility in agricultural education: A social learning theory approach. Journal of Agricultural Education, 31 (1), 75-79.

Goodlad, J. I. (1984). A place called school: Prospects for the future . New York: McGraw-Hill.

Han, Y. (1994). The impact of teacher’s salary upon attraction and retention of individuals in teaching: Evidence from NLS-72. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans, LA.

Harper, J. G. (2000a). Expert opinions of the future of agricultural education in Illinois . Retrieved December 16, 2002, from http://www.agriculturaleducation.org/ap/research.htm

Harper, J. G. (2000b). Public perceptions of the future of agricultural education in Illinois . Retrieved December 16, 2002, from http://www.agriculturaleducation.org/ap/research.htm

Heneman, H. G., Schwab, D. P., Fossum, J. A., & Dryer, L. D. (1980). Personnel-human resource management . Homewood, IL: R. D. Irwin.

Holland, J. L. (1973). Making vocational choices: A theory of careers. Englewood Cliff, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Howell, J., & Avolio, B. (1992). The ethics of charismatic leadership: Submission or liberation? Academy of Management Executive, 6(2), 43-54.

Hughes, M., & Barrick, R. K. 1993). A model for agricultural education in public schools. Journal of Agricultural Education, 34 (3), 59-67.

Jantzen, J. M. (1981). Why college student choose to teach: A longitudinal study. Journal of Teacher Education, 32 (2), 45-49.

Joseph, P. B. & Green, H. (1986). Perspectives on reasons for becoming teachers. Journal of Teacher Education, 37 (6), 28-33.

Knight, J. (1977). Why vocational agriculture teachers in Ohio leave teaching. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, The Ohio State University.

Knobloch, N. A., & Whittington, M. S. (2002). Factors that influenced beginning teachers' confidence about teaching in agricultural education. Proceedings of the annual meeting of the AAAE Central Region Agricultural Education Research Conference (pp. 1-12). St. Louis, MO.

Kuh, G.D. (2001). The National Survey of Student Engagement: Conceptual framework and overview of psychometric properties. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research. Retrieved October 25, 2005 from: http://nsse.iub.edu/html/research.htm

Ladwig, S. A. (1994). A teacher’s decision to stay or leave the teaching profession within the first five years and ethnicity, socioeconomic status of the teacher’s parent(s), gender, level of educational attainment, level of educational assignment, intrinsic or extrinsic motivation, and the teacher’s perception of support from the principal (Doctoral dissertation, University of La Verne). Dissertation Abstracts International, 55, A1208.

Leithwood, K. (1994). Leadership for restructuring. Educational Administration Quarterly, 30 , 498-518.

Leithwood, K., & Jantzi, D. (1997). Explaining variation in teachers’ perceptions of principals’ leadership: A replication. Journal of Educational Administration, 35 (4), 312-31.

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Larkin, K. C. (1986). Self-efficacy in the prediction of academic performance and perceived career options. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 33(3), 265-269.

Lent, R. W., Hackett, G., & Brown, S. D. (1996). A social cognitive framework for studying career choice and transition to work. The Journal of Vocational Education Research , 21(4), 3-31.

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D. & Hackett, G. (1996). Career development from a social cognitive perspective. In D. Brown & L. Brooks (Eds.), Career choice and development (3rd ed., pp. 373-421). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Litt, M. D., & Turk, D. C. (1985). Sources of stress and dissatisfaction in experienced high school teachers. Journal of Educational Research, 78 , 178-185.

Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and personality. New York: Harper & Brothers.

Marlow, L., Inman, D., & Betancourt-Smith, M. (1996). Teacher job satisfaction. ERIC Document Reproduction Service (No. ED 393802).

Marso, R., & Pigge, F. (1994). Personal and family characteristics associated with reasons given by teacher candidates for becoming teachers in the 1990's: Implications for the recruitment of teachers. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Midwestern Educational Research Association, Chicago, IL.

McCampbell, W. H., & Stewart, B. R. (1992). Career ladder programs for vocational educators: Desirable characteristics. The Journal of Vocational Education Research, 17 (1), 53-68.

McCoy, J. S., & Mortensen, J. H. (1983). Recent Pennsylvania agricultural education graduates: Their academic ability and teaching status. Journal of the American Association of Teacher Educators in Agriculture, 24 (3), 46-52.

Miller, J. E., & Muller, W. W. (1993). Are the more academically able agriculture teacher candidates not entering or remaining in the teaching profession? Journal of Agricultural Education, 34 (4), 64-71.

Moss, J., & Briers, G. E. (1982). Relationships of attitudes of vocational agriculture student teachers and their plans to teach. Paper presented at the National Agricultural Education Research Meeting, Orlando, FL.

Moss, J., Jr., & Liang, T (1990). Leadership, leadership development, and the national center for research in vocational education. Berkeley, CA: National Center for Research in Vocational Education.

Moss, J., Jr., Leske, G. W., Jensrud, Q., & Berkas, T. H. (1994). An evaluation of seventeen leadership development programs for vocational educators. Journal of Industrial Teacher Education, 32 (1), 26-48.

National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future. (1996). Forecasting the labor market for highly trained workers . New York: Author.

Ochsner, N., & Solmon, L. (1979). Forecasting the labor market for highly trained workers. Los Angeles: Higher Education Research Institute, University of California, Los Angeles.

Ogawa, R.., & Bossert, S. (1995). Leadership as an organizational quality. Educational Administration Quarterly, 31, 224-243.

Parker, J., & Merrylees, S. (2002). Why become a professional? Experiences of care-giving and the decision to enter social work or nursing education. Learning in Health & Social Care, 1 (2), 105-114.

Pucel, D. J. (1990). Relationships between experienced postsecondary vocational teacher needs and their career development. Journal of Vocational Education Research, 15 (4), 19-36.

Richardson, A. G. (1988). Why teach? A comparative study of Caribbean and North American college students’ attraction to teaching. Journal of Vocational Education Research, 15

Rousan, L. M., & Henderson, J. L. 1996). Agent turnover in Ohio State University extension. Journal of Agricultural Education, 37 (2), 56-62.

Ruhland, S. K. (2001). Factors that influence the turnover and retention of Minnesota’s technical college teachers. Journal of Vocational Education Research, 26 (1), 56-76.

Sashkin, M., & Sashkin, M. (1990). Leadership and culture building in schools: Quantitative and qualitative understandings. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Boston, MA.

Sashkin, M., & Walberg, H. J. (1993). Educational leadership and school culture. Berkeley, CA: McCutchan Publishing Corporation.

Seng Yong, B. C. (1995). Teacher trainees’ motives for entering into a teaching career in Brunei Darussalam. Teaching and Teacher Education, 11 (3), 275-280.

Serow, R. C., Eaker, D., & Ciechalski, J. (1992). Calling, service and legitimacy: Professional orientations and career commitment among prospective teachers. Journal of Research and Development in Education, 25 (3), 136-141.

Silins, H. (1994). The relationship between transformational leadership and school improvement outcomes. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 5 (3), 272-98.

Sweeney, J. (1981). Teacher dissatisfaction on the rise: Higher-level needs unfulfilled. Education, 102, , 203-207.

Thom, D. J. (1992). Teacher trainees’ attitudes toward the teaching career. The Canadian School Executive , November, 28-31.

Toppin, R., & Levin, L. (1992). “Stronger in their presence.” Being and becoming a teacher of color . Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Francisco.

Trusty, F. M., & Sergiovanni, T. J. (1966). Perceived need deficiencies of teachers and administrators: A proposal for restructuring teacher roles. Educational Administration Quarterly, 2 , 168-180.

Tschannen-Moran, M., & Woolfolk Hoy, A. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17, 783-805.

Vroom, V. H. (1964). Work and motivation. New York: Wiley.

Walsh, W. B. & Huston, R. E. (1988). Traditional female occupations and Holland’s theory or employed men and women. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 32 , 358-365.

Wankat, P. C., & and Oreovicz, F. S. (1993). Teaching engineering. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Wardlow, G. (1986). The academic ability of agricultural education graduates and their decision to teach. Paper presented at the meeting of the 10th Annual Research Conference in Agricultural Education, Chicago.

Wicker, E. B. (1995). Factors that have influenced the career development and career achievement of graduates of Lincoln Hospital School of Nursing (Doctoral dissertation, North Carolina State University, 1995). Dissertation Abstracts International, 56 , 1217A.

Wonacott, M. E. (2001). Leadership development in career and technical education (Grant No: ED-99-CO-0013). Columbus, OH: ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult, Career, and Vocational Education. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED452366).

Wright, M. D. (1985). Relationships among esteem, autonomy, job satisfaction and the intention to quit teaching of downstate Illinois industrial education teachers (Doctoral dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1985). Dissertation Abstracts International, 46 , 3273A.

Wright, M., & Custer, R. (1998). Why they enjoy teaching: The motivation of outstanding technology teachers. Journal of Technology Education, 9 (2). Retrieved December 9, 2002, from http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/ejournals/JTE/v9n2/wright.html

Young, B. J. (1995). Career plans and work perceptions of preservice teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education , 11(3), 281-292.

Acknowledgments

This material is based upon work supported by the Illinois State Board of Education, Facilitating Coordination in Agricultural Education and Cooperative State Research, Education and Extension Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, under Project No. ILLU-793-331. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the view of the Illinois State Board of Education or U.S. Department of Agriculture. This article was presented as a research paper at the 2005 Career and Technical Education Research Conference in Kansas City, MO.

The Authors

Breanne M. Harms is an Area Manager, Parts and Service Sales for John Deere Company – Kansas City Sales Branch, 1312 W. 43 rd Street, Hays, KS 67601. Email: HarmsBreanneM@JohnDeere.com . Phone: 785-650-0180. Fax: 785-650-0153.

Neil A. Knobloch is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Human and Community Development at the University of Illinois , 139 Bevier Hall, 905 South Goodwin Avenue, Urbana, IL 61801. Email: nknobloc@uiuc.edu . Phone: 217-244- 8093. Fax: 217-244-7877.