JARS v42n2 - The Natives Are Wild

The Natives Are Wild

Reported by Fred Galle, Hamilton, Georgia

Reprinted from the "Rosebay", Massachusetts Chapter publication.

Hey, man! It's time we raise our beautiful heads and speak out. We've been run over, bulldozed and burned for too many years. We need to show our color and blow our trumpets (tubes). Have a rally, page the White House, everyone is doing it today. I can see it now, banners proclaiming N A B (Natives Are Beautiful). We need to hit the streets and stand firm and proud in the gardens.

We've had poor PR being called "Wild Honeysuckle". Many of our rank (species) share beautiful fragrance with the honeysuckle, but then we part company and do not become a pest rambling and climbing over everything. We stand proud after being well planted and display our beauty throughout the years.

|

|---|

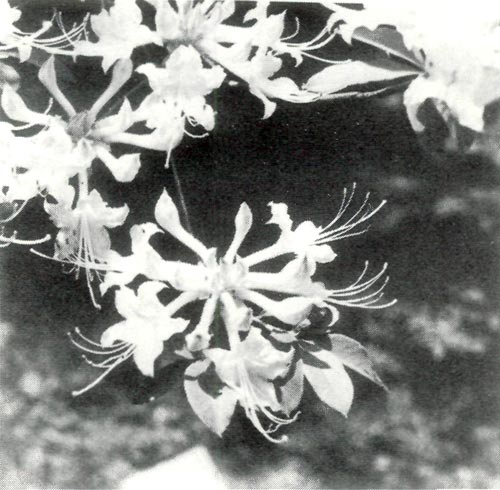

R. calendulaceum Photo from Fred Galle, Callaway Gardens |

We rightfully should be called "Queen of the Woods". With a good name it would not have taken so long to be recognized. Way back in 1790, William Bartram called R. calendulaceum the Flame Azalea and summed up "this is certainly the most gay and brilliant flowering shrub yet known". How true it is. Just think what he might have written if he had knowledge of all the brother and sister species we know today.

I just learned this year that in a remote area of the Carolinas we are called "Whippoorwill". I am not sure why we were given this name. The Whippoorwill is a bird seldom seen but certainly its call at night is readily recognized by everyone. Perhaps we share the Whippoorwill name as a welcome call in the spring as they call their mate and we azaleas begin to show our beautiful flowers.

Our seventeen species (plus or minus, depending on the botanist) have great fun swapping genes; and like proud parents our progeny are often very beautiful and defy classification. There are some who claim that as species we do not hybridize in the wild. Well, they have never been in the bush in the spring and seen the fun finding some of our beautiful seedlings. Some of us do segregate due to flowering season and other factors. However, when two or more of us are in the same area and flowering; brother, do we integrate. In fact, we've been doing it long before those smart folks could spell the word.

Two of our species from the Section Rhodora , R. canadense and R. vaseyi do not cross readily with other species. They are known for their split petals and extra stamens. R. canadense is also a tetraploid (2 N = 52), while most of us are diploids (2 N = 26). R. canadense was crossed with an oriental species R. japonicum in 1912 by Mr. G. Fraser of Vancouver, British Columbia and a cultivar is named 'Fraseri'.

R. occidentale as a lone species on the west coast is typically a diploid but tetraploids and even hexaploids (2 N = 78) have been reported. They have produced many beautiful progeny in the wild. Plus with help, with hand pollination, R. occidentale crosses with its eastern cousins. 'Washington Centennial' is a knock out, developed by Dr. Frank Mossman; a cross of ( occidentale x bakeri ) x 'Santiam'. It will be released in 1989 for the Washington State Centennial.

R. calendulaceum , the beautiful Flame Azalea, is also a tetraploid and was thought not to cross readily with other diploid species or that the progeny would be triploids and sterile. Few triploids have been reported and most of the offspring of the Flame Azalea and a diploid native species are usually tetraploids.

While colorful hybrids often puzzle botanist and horticulturist they are a delightful addition to the garden. Some even describe our colorful hybrids as species such as R. furbishi , a natural hybrid of R. calendulaceum x R. arborescens , and R. coryi is now considered by most as a variety of R. viscosum . Some folks, (splitters) disagree with others (lumpers) as to our specific standards and feel that R. bakeri and R. cumberlandense should be treated as separate species. Now a new proposal (heaven forbid) is that R. bakeri is a hybrid and should be renamed R. cumberlandense .

If that's not enough confusion most horticulturists have difficulty in accepting species name changes (usually made by botanists). It's true we were first given different generic names such as Azalea viscosa and Biltia vaseyi , and most of us now accept the generic name Rhododendron . However accepting changes in the species name due to priority of publication is often a hard pill to swallow, and costly when making changes in publications and catalogs. The new changes are R. flammeum (syn. speciosum ), R. prinophyllum (syn. roseum ) and R. periclymenoides (syn. nudiflorum ).

We all feel sad for the Pinxterbloom alias R. nudiflorum that was used and accepted for over 140 years to now have such a tongue twisting difficult to spell name as R. periclymenoides . Maybe some day those folks will standardize a name that has been in use for 50 or 100 years. Oh well, life goes on and we feel sure old Pinxterbloom will still be remembered by its old name R. nudiflorum . Frankly we'll never tell or correct you.

Often we have not been accepted, some stating that natives are hard to transplant. It's true transplanting from the wild is difficult when you leave most of our roots behind. Look at our roots, we have basically two types, a shallow fibrous root system and a stoloniferous root system that develops into large plant colonies. Our roots often exceed 8 to 10 feet from the parent plant and in stoloniferous plants extend 30 to 50 feet in light sandy soils.

Is it any wonder why we are difficult to transplant from the wild when you dig a 15 to 18 inch ball? Man, you have left over 50% of our fine fibrous roots. We cannot maintain our tops with less than 50% of roots unless you remove some of our branches to compensate for root loss. From the roots you left behind we often develop a complete ring of new plants around the shallow, hole you left. Hey, some smart guy said let's try root cuttings and it works.

|

|---|

R. viscosum Photo from Journal files |

The stoloniferous root system is common with R. atlanticum , R. viscosum and R. canadense . The following occasionally have stoloniferous root systems: R. arborescens , R. alabamense , R. canescens , R. oblongifolium , and R. periclymenoides ( nudiflorum); and rarely with R. prinophyllum (roseum) and R. flammeum (speciosum) .

A secret that is not generally known is that we stoloniferous plants are usually easier to root from cuttings and you can divide us and make root cuttings. We even can carry over this ease in rooting when we are crossed with non-stoloniferous plants. How about that!

|

|---|

R. alabamense Photo from Fred Galle |

The main thing troubling garden folks is that we are hard to identify. Right? Well, some folks have special features of anatomy they like to observe. With natives you have got to take in our complete morphological features such as: floral buds, color and shape of flowers, season of bloom, length of tubes, and all the presence or absence of pubescence, glandular seta or bristles and hairs (botanists use a formal term trichome) on our leaves, flower tubes, lobes and stems. If that is not enough, smell whether we are fragrant or not. We species can be identified by using some of those fancy keys that folks make. They are tricky to use and by golly our beautiful natural hybrids will give you fits 'cause we don't follow the keys with all our different features.

This is not a botanical discourse but perhaps a few lists will help.

GLABROUS STEMS - R. arborescens , R. prunifolium

NON GLANDULAR FLOWER TUBES - R. prunifolium , R. flammeum

LOBES DIVIDED NEAR OR TO THE BASE - R. canadense 10 stamens, R. vaseyi 5 to 7 stamens

PUBESCENT BUDS - R. austrinum , R. canescens , R. canadense , R. occidentale (also glabrous), R. prinophyllum , R. viscosum , Occasionally R. atlanticum will be pubescent.

As another example: R. prinophyllum (roseum) has a short tube rapidly flaring, pink flowers and a pubescent bud as compared to R. periclymenoides (nudiflorum) .

It's true, you must remember all of these special and neat features for the species and cast them to the wind when you meet some of our beautiful natural hybrids. Oh, we know there are some folks who on spotting a hybrid try to give our parentage. Do they really know or are they just guessing? With some study one can often guess if only two species are involved. However, remember we have been integrating for many years and when 3 or 4 of us are in the same woodland flowering at the same time we can have great fun swapping genes. Then when you come in and hand pollinate us, wow! All rules are broken.

|

|---|

R. canescens Photo from Journal files |

Today one has to expose all, for a look at our insides. Fortunately most gardeners do not have microscopes and chemistry laboratories to do this. Our small seeds have now been examined and described. Did you know that two of us have un-winged seeds, R. arborescens and R. vaseyi , while the others have winged seeds? Our wings while small are distinct and the type of lobing at the hilum region vary with each species. In fact R. canadense has a distinct type of wings unlike any other species, with lobing all around the seed.

Now those folks in white coats are looking at us through electron microscopes to examine our hairs (trichomes) and glands. Chemotaxonomic studies are underway checking our flavonoids (lucky we have no blood).

Nothing new under the sun? You have not looked with eagle eyes, but please hurry for time and happy hunting sites are rapidly disappearing. By golly just look at the neat native cultivars, introduced by Beasley, Carlson, Holsomback (Cherokee Series), Leach, Weston and others. Soon to be reported are the Varnadoe selections from Georgia and the Appalachian Series by C. Towe of South Carolina.

Several years ago we had no reports of double flowered natives and now there are at least three from Georgia. 'White Flakes' and 'Sara Copeland' are white doubles of R. canescens . Now soon to be registered is a reddish orange, hose-in-hose double, of R. flammeum found by P. Schumacher.

Each new discovery has an interesting story. 'Millie Mac' is an exciting selection of R. austrinum discovered by F. McConnell while cruising timber in Escambla County, Alabama and named for his wife. It must be seen in living color to enjoy, with vivid yellow petals, a wide wavy margin and fragrance to top it off.

Now the luck of the collector, in 1965 over a 1000 acres of land was clear-cut and bulldozed west of Atlanta, Georgia near the Chattahoochee River for a new Southeastern Industrial Park. Callaway Gardens was alerted and collected over 500 dormant plants from the area. Unfortunately the site had never been explored in the flowering season. Mrs. Norma Seiferle, an active botanist from Atlanta, collected twelve dormant plants at random later from the same area and planted them at her home. Three plants planted together (and again collected at random) had pink flowers with thin narrow split petals. The other 9 plants, planted in other sections of the garden, had typical tubular pink to yellowish pink flowers of hybrid origin. One of the split petaled plants was registered as 'Chattahoochee' in 1982. This was first registered as a mutant of R. canescens but due to its glabrous flora buds is now listed as a R. flammeum hybrid. It is possible that R. alabamense was also in the area but we will never know for the site has been expanded and no original vegetation was left.

Luck, you bet, and thanks to Norma for collecting twelve plants. Just stop, dream and speculate what might have been found flowering in the area on a beautiful spring day. Well, the story is winding down but it is not complete. Hybridizing in the wild and by dedicated gardeners is still going on.