JARS v44n2 - Red Hills, Limestone Mountains and Yunnan Rhododendrons

Red Hills, Limestone Mountains and Yunnan Rhododendrons

Gwen Bell

Seattle, Washington

Mountain Travel set the tone for our journey into Yunnan, a province in southwestern China, in May of 1989, when they suggested, "Be flexible and cultivate a sense of humor." This advice proved invaluable for the thirteen members of the Warren Berg Yunnan Exploratory Trip.

Our adventure began when we reached Kunming, capital city of Yunnan Province, on May 13. This city is located at 6,200 feet altitude and was described once as a city with no summer season, just a very long spring that moves directly into autumn. There is a mix of old Chinese culture and new in the small shops, crowded dwellings and narrow busy streets. Solar panels are installed on a few rooftops of the old buildings, modern busses serve Kunming citizens and most of the locals wear western dress, whether they are on foot or on the thousands of bicycles that carry them about their business. Some of the myriad of smells in all the towns that we entered were pleasant, some were unrecognizable and some not at all nice. It was exciting to realize that we walked along streets of a city so very important to plant hunters of the past, the city known then as Yunnan-fu.

Late in the afternoon of our first day in Kunming, we put into practice our initial attempt to be flexible. We were told that the four-wheel-drive vehicle promised us would not be available after all. Warren, John Thune, our trip manager and Jiang, our Chinese manager for Yunnan Province conferred and reached an agreement. Our party would ride in a mini-bus and our duffle bags, tents, medical supplies and food would be transported in a Toyota truck. Unfortunately, this compromise meant that we would not be able to go as high in the mountains as originally planned.

The second disappointment occurred when it was announced that permission to visit the Weixi area (Wei-Hsi) had been withdrawn. It was explained that Weixi was too close to the Tibetan border and conditions there too unsettled. An assistant truck driver speculated that the Chinese army was moving troops in that district at night. It was obvious to us that the Chinese Tourist Agency was genuinely concerned for our safety, but it is highly likely that they did not wish us to observe any army movements either.

A special Sunday visit to the Kunming Botanical Garden was arranged and even though it rained heavily at times, we managed to enjoy the stroll through the garden. We saw numbers of flowering plants and conifers. Camellias, roses and rhododendrons dripped moisture. Most of them had bloomed earlier, but we recognized rhododendrons from the Thomsonii series, also R. arboreum , decorum , hemsleyanum , crassum and yunnanense . Low, white and pinky-white azaleas bordered beds of larger shrubs. Most of the azaleas were unidentified, but appeared to be forms of R. mucronatum . Kunming Botanical Garden is not extensive, but it is gratifying to know that the botanists and plants people are collecting their native rhododendrons together in order to study and preserve them.

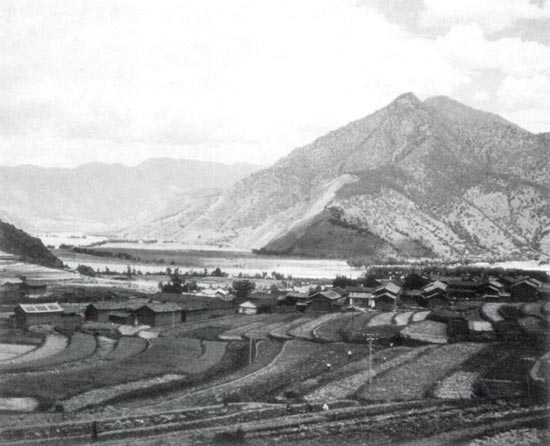

On the morning that we began the six-to-eight hour journey northward to Dali (Tali-fu), we traveled through what is essentially dry country. With irrigation, the land is fertile and intensely cultivated. The unfamiliar sight of water buffaloes treading in the flooded fields captivated us. Rice was being planted in the paddies, barley was turning golden and it did seem that every inch of level ground was planted or about to be planted. Terraced hillsides provided more fields. Even the steepest slopes were under cultivation. It was difficult to believe that those high terraced slopes could withstand the driving monsoon rains which were due in June. Corn, vegetables, watermelon, wheat, millet, soy beans, cotton and tobacco fields were responding to sun, water and "night soil." We saw relatively few orchards although the climate of this region would seem to be ideal. We developed a real hunger for fresh fruit during our stay in China.

For the most part, in these rural areas, flowers grew in containers. There were few private ornamental gardens. In the courtyards of the hotels and guest houses that we frequented, camellias, rhododendrons, azaleas, iris, chrysanthemums, geraniums and peonies grew in tubs. Bougainvilleas and wisterias climbed on frames, over walls or draped gracefully over low buildings. Cheery, colorful roses were usually spaced out in beds. What was mildly surprising was the number of newer hybrid roses. Clematis, too, trailed over posts and walls. Soon it became a game for us to identify the containerized rhododendrons. We easily spotted R. decorum , delavayi , neriiflorum , racemosum and uvariifolium . Some plants did not key out, perhaps being hybrids. In Lijiang a fine display of bonsai decorated one end of the patio.

Since Weixi was denied us, Lijiang, the 800-year-old city that was well-known to the plant collectors, was selected as a promising substitute. Lijiang rests on a high plateau, in a northerly direction from Kunming. Along the way, we gazed at red-colored hills and ranges of mountains, while advancing upward to 8,000 feet. Rhododendron yunnanense dotted the hillsides with soft pink color. A ring of mountains surrounds Lijiang and its valley. The broad valley bottom, near the old city, is fertile and there is a timber industry.

The majority of people here are from one of the eight ethnic groups in this part of Yunnan, the Naxi (Nakhi). These Naxi believe that an old god, Tabu, helped their ancestors to hatch from magic eggs. The Naxi and the Bai live and work in "old town," while the smaller numbers of Han Chinese live in "new Lijiang." This city was famous as a gathering place for the tribes people, now called the "minorities."

From the guest house, we walked through glaring sunshine to the spacious, park-like grounds of the Black Dragon Temple. Our particular reason for braving the heat at mid-day was to search out patches of R. racemosum reported to grow on the steep hillside behind the temple. These racemosums were the first stands of native rhododendrons seen since entering China, excepting some R. yunnanense .

Now we eagerly began our hunt for rhododendrons high in the mountains. Our mini-bus carried us out of Lijiang and onto the dry plain where the thirteen peaks of the Yulong Shan loomed up in spectacular fashion. Its jagged, snow-covered peaks and white glaciers rose above the plateau higher than 18,000 feet. The day was sunny and hot, clouds of dust boiled around the bus. If another vehicle approached, we shouted "windows" and the windows all around the bus slammed shut. Along side the river that we followed, our driver stopped the bus and we hustled out. We hurried across the bridge, then looking upwards, we were entranced by the crystal-clear, beautiful sight of Snow Dragon Jade Mountain.

Our march up that mountain followed the course of a narrow tributary. Smooth, rounded, bleached rocks and boulders spread out on both sides of the stream. At first the climb was easy. As the walls of rock rose, fencing us in, it grew increasingly difficult to climb out of the cut. The rewards for our efforts began to appear. Tiny, young rhododendrons nestled at the base of boulders and small seedlings of miniatures hugged the shady, moist patches. Their foliage was typical of the lapponicums and the trichostomums. Rhododendron impeditum , wearing an intense "blue" color, seemed to be growing right out of the rock wall. A smokey-blue clematis was fighting to survive in the baked and inhospitable conditions between boulders wedged above the riverbed. We climbed higher and higher, each at his own pace, but always keeping in sight or sound of others in our party. Each carried a whistle to summon help if the need arose. Plant hunters wrote that the mountains of the Yulong Shan and other Yunnan ranges were almost solid limestone, magnesium limestone. Bruce Leber took soil samples and did indeed find that these mountains were limestone. Some rhododendrons had acid duff at their roots. [Bruce Leber's observations are in an accompanying article.]

June Sinclair experienced the most hair-raising adventure of this climb when she scrambled up a steep scree, trying to get a closer view of the leathery-leafed Solms-Laubachii pulcherrima . This plant is said to have large blooms of a fine turquoise-blue. Slipping in the loose rocks and gravel, unable to find stable handholds or to lean back far enough to see footholds that would take her down, her strong fear of heights began to kick in. It was almost panic time. Her climbing partner, Garratt Richardson, assessing the danger, calmly talked her down by suggesting where she should place hands and feet at each step.

It was like finding treasure to spy thrifty plants of R. trichostomum var. ledoides , R. chryseum , well-branched R. primuliflorum , midget R. impeditum and dwarf hypericums seeding themselves on the mosses. Cypripedium and rose-colored pleione orchids flourished among the rock crevices, along the track or on grassy knolls. Taller bush and tree-like species were showing few flowers, although the plants of R. decorum , yunnanense , rubiginosum , and uvariifolium were good. Rhododendron adenogynum was attractive as was the species that we used to call R. rigidum . Young shoots of R. beesianum flaunted thickly indumented foliage. They should become handsome mid-sized trees. What appeared to be stalks of tree peony stood fifteen inches high, and as yet had pushed no flower buds. Pine trees were the most prolific of the trees on this mountain. Dwarf berberis and cotoneaster grew as groundcovers, spreading out flat near the track and even underfoot.

Though our altitude sickness preventive seemed effective, we did notice that it required determined effort to climb up and down and over the rocks. In fact, we rested frequently at this 10,800 to 11,000 foot level.

On May 18, with the truck trailing behind our bus, we began the long day's ride to the Litiping district. Again we saw those red hillsides as we descended to 6,700 feet and then began to rise steadily onto a ridge where we could survey a tremendously high range of snow-crowned mountains in Burma. Those peaks reached up into the soft atmosphere with a ghostly quality. We were fortunate on that lonely road to meet, from time to time, a foot-traveler who could reassure us that we were on the right track to Litiping.

Rhododendron decorum was the most prolific of the rhododendrons on the slopes. Some forms looked superior and were blooming at a surprisingly young age. In Litiping, R. rubiginosum grew everywhere. At last, we reached a road maintenance station, where we settled ourselves to wait while Warren, John and the young Chinese interpreters, Cathy and Francis, forged on in the truck, scouting for the highest suitable campsite. Almost three hours later, we conceded that the best place to set up camp was directly across the lane from the road station. There on a fairly level stretch of ground, cattle had worn trails through the grasses. Across the road, pigs and a parade of ten piglets squealed in the courtyard, while dogs and geese patrolled the track.

We raised our tents as quickly as possible as twilight approached, then we continued a preliminary survey of the hillside behind our camp. Clumps of rose-colored R. rubiginosum , stretching eight feet high, crowded between the animal trails. We skirted around and between clusters of young plants of R. uvariifolium , the expanding leaves were coated with soft wooly white indumentum. A plant that puzzled us at first, we determined to be R. lukiangense . A short walk from camp brought us to a low knoll covered with bunches of good pink-flowered R. racemosum . Adjacent to them, on the open, sunny knoll grew colonies of low, "blue" R. polycladum . Fragrant blossoms of gnarled apple trees scented the air.

|

|

R. lukiangense

, at Litiping, 11,800 feet.

Photo by Warren Berg |

That evening, while our meal was being prepared at the road station, we felt particularly excited. Here we were camping among fields of rhododendrons. In that dusty courtyard, we sang songs, listened to the road crew's canned music and, later, as the moon was rising, heard a wonderful musical sound. From afar, drifted the notes of a native flute. During the night the dogs barked, a wolf howled and the coo coo birds called and called. Occasionally cows plodded past the tents, snuffling at the intruders. Next morning Janet Lindgren discovered a leech clinging to the side of her tent. It was one and a quarter inch long, black and shiny, looking like a twig.

After adjusting our backpacks, we struck out enthusiastically on the morning's hike up the logging road above the maintenance station. The sight of the decimated mountainside forced a vivid impression on us. Such messy, wasteful logging operations are unfortunate for a country that has a great need for timber. But where trees had stood, rhododendrons were generating. Rhododendron oreotrephes scattered itself among the R. rubiginosum . The most interesting species here were thickets of R. mekongense var. mekongense and R. mekongense var. melinanthum . Their blossoms reflected sunlight and their leaves showed the typical ciliate margins. These shrubs were three-to-four feet high. Not far away, near a bend in the track, grew a few four-foot tall rhododendrons that were clearly hybrids between R. rubiginosum and R. racemosum . Flowers were a strong pink color, somewhat racemose and large. If material from them could have been collected, we could have had excellent new material for our gardens. Soil here seemed drier than on the Snow Dragon Jade Mountain. There was not much scrub and underbrush among the rhododendrons. Perhaps the cattle browse off the tender new shoots in the spring. Hot springs abound in Litiping, indicating the probability of past volcanic action.

|

|

R. oreotrephes

, 99 Dragon Pool area, 9,800 feet.

Photo by Warren Berg |

Reaching the mountaintop at 11,800 feet, we could see beyond the Weixi Valley and into Tibet. On the valley floor were numbers of Quonset-type greenhouses sheltering rows of ginseng. On the broad peak, we found the remains of a monastery or lamasery and what may have been a radio tower. Don King picked up a broken shard of pottery and read the date 1972 imprinted upon it. It is probable that the monastery was attacked during the Cultural Revolution which raged between 1966 and 1976. Near this place of ruins were small almost level areas covered with very dwarf, bright pink flowering bushes of R. racemosum , looking like bunches of heather, well protected from the ever-present winds.

That night, when the orange moon was full, three young girls of the Yi tribe came to visit. They were curious about us and we were delighted to see and photograph them. These very attractive sisters, fourteen, fifteen and eighteen years old, had walked many miles to reach our camp. Their long skirts and large, rather squared headdresses were especially colorful and charming in bright hues of red, gold, white, navy and turquoise-blue. Occasionally we glimpsed women working in the fields dressed in similar costume. These Yi girls had never been to school, had never seen Americans and had never ventured farther afield than the village nearest their home.

|

|

Young girls of the Yi tribe, Litiping camp.

Photo by Warren Berg |

Enroute from Litiping to Judian, we discovered that one of the mini-bus tires was losing air. A repairman squatted in the near-by river, revolving the tire tube around and around in the water until the leak was discerned. Total cost of the tire repair at that rural garage was four yuan, about $1.00.

By this time, we had formed some observations about road travel in China. Generally, the roads were in good shape, though narrow. Many times these highways seemed overloaded with trucks and busses. The only automobiles appeared to belong to party officials or VIPs of some sort. It is the rules of the road that are difficult to understand. Sometimes two vehicles, moving in opposite directions, compete for passing space around slow-moving machines at the same time on roads that are only two lanes wide. There were shocking near-misses. Still, honking the horn continuously always helps . . . does it not!

|

|

View of the great bend of the Yangtze River at Shigu.

Photo by Warren Berg |

It is near Shigu (Zheju) that we caught the first sight of the historic "Great Bend" of the Yangtze River. Plant explorers noted that this river meant life or death to the many Chinese and tribes people who lived along it or who earned their living from it. For many centuries it has been called the "Long River" for it extends 3,915 miles and passes through ten provinces. We prevailed upon our guides to stop the bus long enough for us to take photos. The day was hot, with sunshine bouncing off the slow-moving water and highlighting the green foliage of the blooming catalpa trees. Near this spot, the Long March, led by Mao Zedong, crossed the Yangtze. Near Shigu is his monument. George Forrest headquartered in Shigu at the time that Tibetan lamas ravaged the area, killing missionaries and those who resembled missionaries. He escaped the slaughter and with great difficulty fled to Weixi. Eventually he was smuggled to Talifu (Dali).

|

|

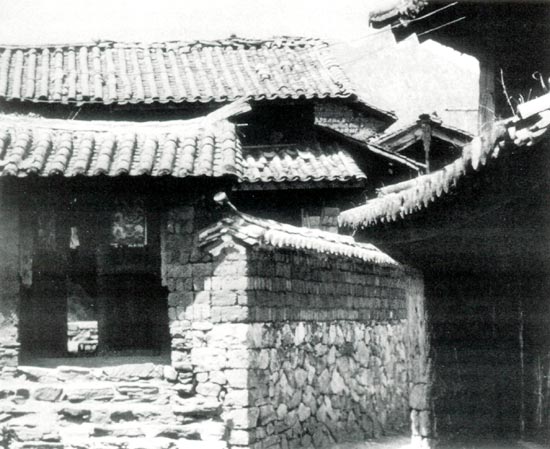

Alley in Shigu.

Photo by Warren Berg |

Sauntering along the hot, gravelly street of Shigu, we saw and entered a pretty, little, walled restaurant named the Garden Court. Geraniums, roses and vines climbed over the walls, brightening the patio and seeming to cool the air. Suddenly, a tiny, brown old woman (perhaps not so old as she looked) chased a well-muscled chicken across the packed earthen floor. Right in my line of vision, she chopped off its head. That was the freshest chicken that we were ever likely to eat, and it rivaled the toughest. The meal featured the Sichuan style of cooking, using plenty of hot peppers.

Due to the flat tire incident, we were running late in our journey to the 99 Dragon Pool area. We met another delay when a logging truck lost its load on the highway. But by lucky chance, Warren and our Chinese guides met the manager of the Heyuan Coal Company. He kindly asked us to spend the night at the mine's guest house. This coal mine is higher than 8,000 feet altitude and is located in a hot springs area. The guest house and a string of row houses, the homes of the miners, front a narrow lane that is shelfed out of the mountainside. Below, on the lower level, is the company store, a large kitchen and dining halls. Potted plants were absorbing sunlight on narrow verandas. Magnolia wilsonii flowered happily in several round pots.

Pat Berg and I were invited to step into a miner's two-room home. The tiny living room was crowded on all sides with family possessions. An aisle-like space surrounded a low, square table in the center of the room. Probably, the most highly prized possession of our hostess was the sewing machine, placed near the only window.

We seemed to acquire more Chinese companions the farther we progressed. Two more Chinese joined us, Mr. Mu, manager of the coal mine, and Mr. Li, a bear hunter. They explained that a group of Chinese students, taken on a field trip into the 99 Dragon Pool district, were attacked by bears. Five students died. Hence, the bear hunter. Happily, we did not see any bears, nor any sign of bear. Mr. Mu and Mr. Li proved to be hard workers and we liked them very much.

The road to 99 Dragon Pool wound steeply upward in a series of sharp curves, interspersed with short straight stretches. Rhododendron yunnanense painted the slopes like a floral print and the red-flowered R. delavayi peeked out from a leafy cover of trees and shrubs. At 11,070 feet, we rounded a gentle curve and were almost stunned to see the facing hillside covered with acres of dwarf "blue" rhododendrons. An involuntary shout rose from the thirteen of us, startling the Chinese and moving of us all to laughter. We snapped photos with abandon, then drove on. Higher we were confronted with more acres of blooming R. racemosum a huge mound of solid pink color. Our driver trotted up the slope to pick an outstanding rhododendron truss, one of unusual form. It was, most likely, a hybrid. The mini-bus crawled upward and onward until a rock slide bought our progress to a halt. Trunks of tall trees stretched across the deeply rutted track. It was a shock to realize that the fallen trunks were rhododendrons.

|

|

Camp at 99 Dragon Pool area,

R. tapetiforme

.

Photo by Warren Berg |

Now it was necessary for the bus to back up cautiously as we searched for the ideal spot, near a stream, to set up camp. The altitude here was 11,500 feet. The cook tent was raised down slope from the road. After a short survey, we selected a flat clearing farther down the hill at the creek's edge for our tents. Cattle and goats roamed on the meadow, indicating that we would need to boil our water the full twenty minutes for safety. Not many rhododendron enthusiasts expect to camp out in the midst of fields of R. racemosum and R. tapetiforme , but that is what we did. It was even difficult not to step on them. Clematis chrysocoma , with lovely four-lobed white flowers and golden stamens, draped and trailed over the scrubby trees.

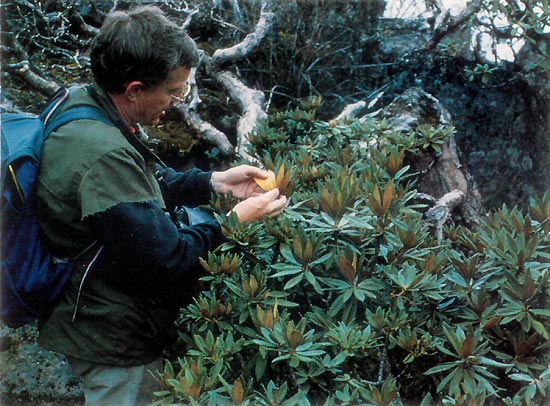

Next day, we rode to the rock slide and then began the relatively easy hike to the trailhead. There the group split, some following the trail to the top of the mountain at 13,700 feet, while others staggered in one-legged fashion up a very steep meadow. Both parties found old and beautiful small trees of R. roxieanum . Their leaves were narrow and felted and their flowers white with the usual smattering of red dots. The big trunks of these rhododendrons indicated considerable age. We identified shrubs of R. traillianum , beesianum , fictolacteum , and alutaceum , but we failed to locate R. pronum which has been described in this area. Scattered among the taller plants were dwarf R. chryseum and R. lapponicum . The 99 Dragon Pool area is rich in attractive rhododendrons, as well as primroses, dwarf bamboos, cotoneasters, iris and, at least, two forms of clematis. This beautiful place had its scars too, the results of inefficient logging operations.

Plant people are currently emphasizing the fact that rhododendrons are disappearing in the wild. In many places, they are cut for firewood. At the upper edge of a large colony of R. racemosum , we noticed that some of them were browned and seemed to be dying. After examination, Lynn Watts concluded that the local herders were attempting to burn the small individual shrubs in order to extend their grazing grounds.

We planned to walk downhill for five miles to a forestry station, observing a variety of rhododendrons as we hiked. We arranged a return ride on the truck being dispatched to a distant village to purchase vegetables. Rain began to drip, but donning our Gortex and raising umbrellas, we trudged on.

|

|

R. litiense

, 99 Dragon Pool area, 10,800 feet.

Photo by Warren Berg |

Rhododendron fictolacteum supported great, round trusses of white flowers. Glowing crimson circles of color in the centers of the blossoms made them more attractive. The foliage was excellent. In shaded areas where soil was moist, smooth-foliaged, rounded bushes opened good yellow blooms. These were R. litiense , but other forms with open faces resembled everything from R. callimorphum to R. wardii . Some of the flowers were clear yellow and some had rings of red color, all were very beautiful.

Hours passed before we reached the forestry station. The rain caused severe discomfort, so we sought refuge in the compound. At last the truck returned, three hours late, giving us another opportunity to "cultivate a sense of humor." On the rough ride back, we bounced around with the boxes of vegetables, fish, two live chickens and what must have been the largest wok in the world.

Every afternoon at about four o'clock, goats ambled through our camp, reminding us again that we were the intruders. Once a local mountain man stopped by and tried to converse. Soon, he decided that we were very stupid and he walked away.

|

|

Jens Birck with

R. roxieanum

at 13,400 ft

Photo by Warren Berg |

The monsoons hit us two weeks early, hampering our explorations. Searching the mountainside directly behind our tents, we discovered a collection of aged R. roxieanum that were sheltered by trees and shrub. Forms recurvum and oreonastes were mingled. Their flowers were a uniform white with crimson spots. Tall R. fictolacteum mixed with them, as well as R. rubiginosum and R. racemosum . Still it rained, making it necessary to trench around our tents to drain the rainwater into the creek. This was our last night at 99 Dragon Pool. All night the rain beat against our tents, but we stayed snug inside. The next morning we heard reports of several rock slides on the upper road.

The journey off the mountain was slow. Every few yards the men left the bus to clear rock and tree debris from the track ahead. At times we all climbed down from the bus to lighten the load where the road was washing away. Rivers and streams were red-brown with mud off those red hills. The water looked as dense as thick soup. Lynn and Bruce reminded us that most of the rainfall in southwestern China occurs during three months of the year. At home in the Pacific Northwest, most of our rain falls in winter and we water on a regular basis during summer. Could this great disparity in moisture contribute to the difficulties sometimes experienced trying to grow Asian rhododendrons?

It was a relief to see the coal mine again, although we had to say goodbye to Mr. Mu and Mr. Li. We continued our descent from the mountains to the valley below, passing by roadside businesses where artisans were laboriously carving granite tombstones, brick kilns were firing and limestone crushers were grinding piles of white powder.

Buildings and homes in this part of Yunnan are handsome. Many are two-storied brick, some are of rammed earth and some are covered with a kind of stucco. In the Dali Valley, buildings often have beautiful paintings of birds, flowers or elegant symbols decorating the area just below the roof peak on each end of the structure.

We arrived safely in familiar Dali, the very old walled city situated on a narrow and fertile plain that extends between the Cangshan (Diang) mountains and the long and important Lake Erhai. Walking the long street between the remaining two gates of Dali is fun. The gates are impressively decorated and watching the vendors while threading one's way through the crowds of shoppers and lookers is interesting. There are no sidewalks, so one stays alert to the sound of horns.

Our hotel in adjacent Xiaguan was old, but had a feeling of aging splendor. Inside the lobby was a rich and beautiful painting on one wall and the other walls were of the Dali marble. Jerry, the young Chinese hotel manager, helped to organize two days of exploration in the Cangshan, west of Dali.

|

|

Cangshan Mountains near Dali.

Photo by Warren Berg |

The Cangshan range is not as beautiful or as impressive as the mountains that we had just explored. Before leaving the courtyard, it was made clear to us that we should stay near the road on this trek. Last year a group of students were on an outing when some of them were bitten by poisonous green snakes. Five students died. Were we hearing an echo? Fortunately we did not see any snakes. The sturdy mini-bus took us up a winding and bumpy road through the marble quarries. Rising to 12,000 feet, we looked back to see Lake Erhai gleaming in the sun, the provider of power, fisheries and irrigation. Rhododendron decorum was the first rhododendron to pop up on these slopes. It is curious that some Chinese eat its flower as a vegetable. Strikingly beautiful bushes of Pieris formosa unfolded brilliant red leaves. On the high side of the road-cut, mingling with dense scrub we saw R. haematodes , a rather small-flowered R. neriiflorum and the gregarious R. yunnanense . The road ended at a huge rock slide and across the gorge a high waterfall trailed a long plume of white spray deep into that gorge. Here the hike began, close to the track!

|

|

R. neriiflorum

, Cangshan Mountains, 11,000 feet.

Photo by Warren Berg |

On the second day, in hot sunshine, we attempted to take a track leading to the new TV tower on top of the mountain at 14,000 feet. Unfortunately but not unexpectedly, the bus refused to negotiate the heavily pockmarked and deeply rutted road. We gave it the good try, but had no choice except to return to the road followed the day before. High up on this little-used road, a crew consisting of two young women, dressed in colorful clothing, cleaned rocks from the roadbed. Rock cliffs absorbed heat from the sunshine and the area was very dry. Though most of Yunnan is rather dry, there is abundant underground water, a legacy from the mountain snows. Clinging to the hot rock walls or tucked into small crevices were tiny plants of R. microphyton . Their small trusses held five or six dainty flowers in cool shades of rose and white. They were more attractive than expected, with petioles hidden under rust-colored hairs. How they get enough moisture to sustain them is a mystery.

Retracing our steps down the track, we arrived at a sharp bend and then looked upward to see a creek forming a little waterfall. The stream rushed downward, swerved in a tight curve around a high and huge boulder, then flowed into a round pool near the road. Jumping from rock to rock, we struggled to the top of the boulder where we found R. edgeworthii hidden among the stunted willow brush. There it was with very crinkled, heavy textured foliage and browned and falling flowers. Off to the side, near the stream, very large arisaemas reared up, obviously loving the misty spray off the waterfall. Yet, only a short distance away, among the rocks, were clusters of cacti.

It seemed a doubly long ride from Dali to Kunming because our adventure was rapidly coming to an end. We were already looking back upon the friendliness of the people that we had met and remembering the experiences shared. Our party was aware of the unrest in China, but at that time, Beijing seemed a long way off and real violence remote. One last bit of excitement occurred when we asked for a rest stop (women to the front of the bus, men to the back). Art Dome, always alert and observant, discovered some straggly R. lapponicum and the only specimen of R. spinuliferum that we were to see in China. This R. spinuliferum produced very small flowers on a very starved-looking plant. These orphaned rhododendrons were fighting for survival on a narrow brushy strip of ground lying between the highway and a long expanse of cultivated fields.

On one of those sunny, golden mornings when we were gathering for the new day's challenge, our Chinese tour members expressed their puzzlement over our enthusiasm for rhododendrons. "Why," they asked, "did you come so far on such an expensive trip, climb so hard and camp out in monsoon weather just to see rhododendrons (their weeds)?" We replied that we wished to study and to photograph rhododendrons in the wild. "But," they retorted, "don't you have any rhododendrons in your country?" Our only reply was, "Yes, we do, but ours are different." I'm sure that they thought us all a bit "touched in the head."

If Jens Birck, who joined us from Denmark, or Charles Larus, from North Carolina, or any of us from the Pacific Northwest were asked, "Would you make this trip to China in search of rhododendrons over again?" I suspect that the answer would be an emphatic "Yes."

Gwen Bell has a special interest in species rhododendron and is active in both the Seattle Chapter and the Rhododendron Species Foundation.