JARS v50n2 - The RSF and Botanical Garden

The RSF and Botanical Garden

Bill O'Neill

Bainbridge Island, Washington

The Rhododendron Species Foundation (RSF) possesses the greatest collection of species rhododendrons in one location as a result of an American Rhododendron Society initiative 35 years ago. Americans attending an International Rhododendron Conference, at Portland in 1961, were made envious by pictures of species unrivaled by plants then available in the USA. As a result, Drs. Milton Walker and Carl Phetteplace formed a Species Project Committee, with the encouragement of then ARS president, Harold Clarke. They were exasperated with the poor quality of species rhododendron plants being sold. Thousands of seedling "species" were being grown without precautions to preclude hybridization and distributed with little attention to quality. The fact that plants of a given species may show considerable variation proved to be both a curse and a blessing. With the cooperation of many throughout the Northwest, the mainly Oregon-based committee coordinated field trips to find, list and acquire the best forms of selected species.

Bird's-eye View

From its inception, the leadership of the RSF had a global perspective. Anticipating an expedition to the United Kingdom in the spring of 1964, Dr. Walker arranged for scions and cuttings to be sent to the University of British Columbia (UBC) in Vancouver, to avoid the fatal fumigation to which U.S. Customs would have exposed them. At UBC, they enjoyed the loving and skilled care of Nick Weesjes and, especially, Evelyn Jack (later Mrs. Weesjes). Walker, and his wife Helen, returned from the United Kingdom with vastly increased knowledge of rhododendrons, strong friendships among British plantsmen, promises of plant material, and the concept of the RSF.

By June 1964, the RSF had a board of directors and was incorporated. One of the first substantial cash contributions came from Ernest Yelton of North Carolina, underlining the principle that the RSF was not solely a Northwestern institution. By November 1964 there were three board members from the East Coast. Although the ARS had set up the Species Project, it was not in a financial position to support the project beyond its original concept of volunteer work within certain chapter areas. Thus, the fledgling had to fend for itself.

Taking Wing

Learning to fly is awkward. Between 1965 and 1971, the RSF founders often doubted they would ever get off the ground. It had been recognized at the outset that "to acquire land, establish plantings and maintain them...an endowment in the neighborhood of one million dollars" would be necessary (1965). The RSF never even visited that neighborhood. Time after time the leaders were frustrated in attempts to interest potential benefactors in the cause. Milton Walker nearly despaired, but he remained generous to a fault and persistently innovative. In 1968, when it was essential to have a place in the United States to grow the developing plants, the Walkers made available their own homestead, near Eugene. Despite the Walkers' waiving the need for any down payment from the RSF, and a way-below-market purchase price, RSF's funds were insufficient to pay the monthly installments. The deal had to be nullified, and the Walkers absolved RSF's substantial debts to them.

In 1971, Jock Brydon, just retired director of Strybing Arboretum in Golden Gate Park, offered to care for the collection at his cherry orchard near Salem, Ore. Members of the Eugene Chapter moved about 800 plants of nearly 400 selected clones that had come from Britain, via UBC, along with specimens donated by Northwestern gardeners (Phetteplace, Fred Robbins, Cecil Smith and Wales Wood). Jock and Edith Brydon dramatically increased the number of cuttings, rooted and grafted, while continuing to gather material from the UBC and abroad. By 1973 it was clear the collection would soon outgrow the space available at Brydons'. Cordydon Wagner, who had negotiated the interim home for the collection in Salem, came up with a new opportunity. He arranged for a presentation to his son-in-law, George Weyerhaeuser.

|

|

R. calostrotum

ssp.

calostrotum

Photo by Steve Hootman |

A Place to Nest

Wagner, Jock Brydon and the RSF president, Fred Robbins, must have made a great impression on Weyerhaeuser and his staff, for by February 1974 arrangements were underway to grant the Foundation use of 24 acres of forested land on the Weyerhaeuser Corporate Headquarters Campus in Federal Way, Wash., between Tacoma and Seattle. The company agreed to provide funding and equipment for clearing and contouring the area, and 37,000 cubic yards of sawdust as soil amendment. It also built fences, roads, pathways, a greenhouse, lath house, office and equipment storage buildings. Those structures, valued at about $350,000, were donated to the RSF in 1978. Weyerhaeuser even provided $45,000 to match money raised by the RSF for operating funds in the period 1975-1977, and 23 Weyerhaeuser employees sponsored the erection of a charming gazebo. Ten years after its emergence, RSF had found a comfortable nesting site.

Solicitations went out to garden clubs and other potential sources for funds and help with which the RSF could feather its nest. Volunteers, from the Eugene and Tacoma chapters of ARS and elsewhere, pitched in to move about 4,000 plants from Salem to Federal Way. Fred Robbins himself often worked six days a week, operating the tractor, planting and generally managing the whole operation. Ester and Bill Avery, along with Warren Berg, coordinated about 30 volunteers to set up a study garden, designed to illustrate phylogenetic relationships. Volunteers from at least a dozen horticultural organizations augmented the small garden staff, ably led by Ken Gambrill.

Until the mid '70s, the RSF had not recruited general membership. A commitment of at least a thousand dollars was expected. Robbins took steps to replace that philosophy with the understanding that a broad membership was needed including those with modest means. By 1978, membership had risen to 455. The garden first opened to the public, during the 1980 bloom season.

Growing Pains

As in most organizations, there have been tensions and conflicts through the years at the RSF. In the early '80s, despite good intentions on practically everyone's part, several resignations resulted from clashes within the staff and between staff members and volunteer Board members serving in the presidency and on the Executive Committee. The eight-person Executive Committee of the Board emerged as the dominant governing body. It, including the president, is chosen for two-year terms by vote of the Board of Directors from among its near 60 members.

When the first executive director, Richard Piacentini, was hired in 1984, membership was at the 750 level. However, financial difficulties soon became apparent. At one point there was only a single staff person in the garden, Rick Peterson, to care for over 25,000 plants. Dr. Herb Spady, as president, and the Board labored with Piacentini and the diminished staff to set the Foundation on firmer financial footing. The debts were paid back and the RSF's endowment increased ten-fold to the $200,000 range between 1985 and 1987.

By its 25th year, 1989, the RSF was in better shape than ever before: there were over a thousand members from 19 countries, and the endowment fund exceeded $300,000. Between 1988 and 1992, RSF operating income was augmented by four federal grants, totaling almost $100,000, won in stiff competition from which RSF was one the few botanical gardens funded. Nevertheless, expenses began to exceed income again in 1991, a situation temporarily offset by a bequest in 1992 from those pillars of the RSF, Milton and Helen Walker. Part of this bequest was also designated to obtain the services of fund-raising professionals who helped boost income briefly in 1994.

|

|

R. rigidum

,

R. davidsonianum

,

R. augustinii.

Photo by Steve Hootman |

Perpetuating The Species

Richard Piacentini resigned in 1991, and his successor, John Fitzpatrick, stayed only a year. It was convenient and fortunate that Scott Vergara, an enthusiastic and well-liked local horticultural educator, was available to take on the executive director's responsibilities almost immediately. Under Scott's leadership, the staff coalesced into a unified team, during a period of tightening financial constraints, aggravated by diminished availability of government funds. Among other improvements, the plants enjoyed increased sunlight from pruning and thinning of the tree canopy. Toward the end of last year, Scott decided to resume his teaching career, leaving the Foundation in the care of a dedicated professional staff, aided by a few interns and many enthusiastic volunteers.

The Executive Committee is assessing the needs and searching for the right individual to deal with the Foundation's financial and public relations challenges. Meanwhile, available resources are aligned to preserve and enhance the collection through the efforts of a professionally cohesive staff under the leadership of RSF Board President Fred Whitney. All are striving to maintain an environment in which the collection and the staff will flourish.

Volunteer participation, always vital to the RSF, is on the rise. Last year, 115 volunteers contributed 5,815 hours of labor (70% more than in 1994), equivalent to adding two and half persons to the paid staff of seven. One can volunteer without even visiting the garden. Several volunteers live outside of Washington, though half the membership resides in this state.

Seasonally the garden staff is augmented by student interns, whose modest stipends are provided by contributions from a few chapters of the American Rhododendron Society. A recent letter, outlining this Intern Program and soliciting more ARS chapters to support it financially, highlighted the need, not only for the garden, but also to imbue young horticultural professionals with the sort of enthusiasm for rhododendrons that we all share. More hands are needed to propagate, keep weeds at bay, mend an aging irrigation system, and improve soil conditions. Nearly a thousand dollars a day (the 1996 budget calls for $351,450) is needed to keep those hands supplied.

|

|

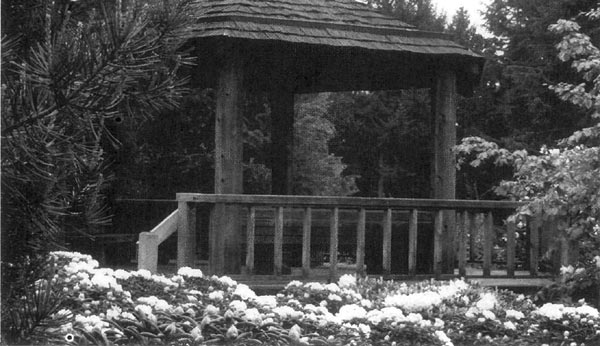

R. yakushimanum

and gazebo.

Photo by Bill Heller |

Family Support

It seems to me that there's something wrong when two-thirds of ARS chapters and 95 percent of ARS members are no longer affiliated with the one organization dedicated to the preservation of their plant species. The RSF is much more than a garden, although the collection assembled as outlined above is its foremost asset. The Rhododendron Species Botanical Garden (RSBG) provides an interesting, informative and beautiful format for maintaining that collection, which now includes some 4,000 rhododendron clones. Furthermore, its nursery produces over 10,000 plants a year for distribution. Plant sales by mail and at the festivals in spring and fall net about $50,000 a year for the RSF. The collection is an unparalleled source of pollen for hybridizers all over.

Last year more than 16,000 people visited the RSBG. Many purchased plants or items from the gift shop, but those purchases and admission fees covered only 28 percent of operating expenses. Together the income from all the above sources provides about two-thirds of the RSF's expenses. Membership dues, unrestricted contributions and grants add up to nearly another third. Membership has remained near a thousand (1,069 in 1995) for the past five years.

Thanks to some additional contributions and favorable investment trends, the endowment was a little over $400,000 last year, still far from the million dollars anticipated by the founders. It is also far short of the level needed to provide stability, though interest on the endowment and funds from the Walker trust help close the gap. However, there are practically no funds available for necessary capital improvements or to recondition the boggy soil areas resulting from the overly generous application of sawdust 20 years ago. The Rhododendron Species Foundation, which has gone through so much to reach this stage, needs and deserves the encouragement and support of ARS members at the chapter and individual levels.

Bill O'Neill lives on Bainbridge Island, Wash., and is a member of the RSF Board of Directors. He would like to thank Slim Barrett, Herb Spady, Fred Whitney, Scott Vergara and the RSF staff for valuable assistance in writing this article, which he hopes will stimulate dialogue by and about the RSF in this Journal. He would also like to acknowledge that this article would have been impossible to write without Slim Barrett's History of the Rhododendron Species Foundation , the publication of which was underwritten by an anonymous donor. All of the book's sales directly benefit the Foundation.