JARS v53n2 - 25 Years of Sikkim's Association with the ARS

25 Years of Sikkim's Association

with the ARS

Keshab C. Pradhan

Gangtok, Sikkim India

The Himalayan state of Sikkim, treasure house of rhododendrons, is, of late, very much in the news as one of the global "hot spots" in the field of biodiversity. With over 40 species, rhododendrons in Sikkim occupy a very prominent place in its ecosystems, a host of unique flora and fauna. The protective area network which constitutes 29 percent of the state's land area of 7300 square kilometers harbors all these species and subspecies of this beautiful genus. If the Sikkim rhododendrons find a safe haven in the protected area network, the ARS has lots of reasons to share our happiness.

The last 25 years was an exciting time in the field of rhododendron studies and activities in this Himalaya wonderland. Time really changed Sikkim, then a monarchy plunged into the mainstream of Indian life. The stalwarts that made Sikkim well-known in the rhododendron world are fast getting out of the scene. This led me to scribble the happenings in the field of rhododendrons during the last 25 years in particular, and a century and a half as a whole, as we are about to step into the new millennium.

When the famous explorer J. D. Hooker visited in 1848 and 1850, Sikkim was a virgin, unexplored botanical wonderland. Hooker, in just two visits, encountered rhododendron species numbering more than 30 - all new to science. He collected seeds of good forms and sent them back to the United Kingdom. It was the beginning of the rhododendron craze in the world. By the end of the 19th century and especially after the publication of Hooker's Rhododendrons of Sikkim Himalayas , Sikkim rhododendrons were well-known in the United Kingdom and parts of Europe. Sporadic collecting tours like that of Cave and Smith from the Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh, in 1910, Ludlow and Sheriff in the late 1930s and early 1940s, and collecting by G. Ghose in Darjeeling and the Chandra Nursery in Rhenock (Sikkim) for special clients, did continue until the mid 1940s. My father, Rai Sahib Bhim Bahadur Pradhan, who was the head of Forest Service in those days, actually helped them in the collections, duly encouraged by the British Political Officer in Sikkim, Sir Basil Gould. Incidentally, Ludlow happened to be in Gould's establishment. When I visited Hobbie's Rhododendron Park in Germany in 1993, Elizabeth Hobbie was excited that I was from Sikkim. She narrated the story of how rhododendron seeds were received by her father in the mid 1930s from my uncle, who owned the Chandra Nursery, and how, as a 5-year-old, she was exposed to rhododendron hybridization. Many of the trees in the park, I was told, were from those crosses.

|

|

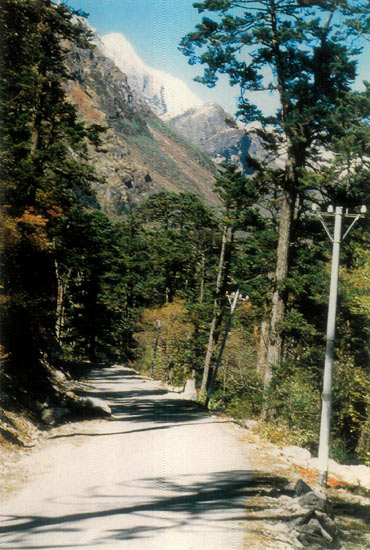

Highway to North Sikkim.

Photo courtesy of Keshab C. Pradhan |

Time rolled by. All around, changes came in the Indian subcontinent. The British Empire after the Second World War was reduced in size. India gained her independence. Sikkim, a buffer state between Tibet and India, became a protectorate. In the mid 1950s, when my father had just retired from the Forest Service, I stepped in as a young forest officer. Since policing the forests were the main activities, my time was utilized mostly in trekking in remote corners of the state. Twenty days in a month was a routine affair. Of course, after I got married in 1963, Shanti and myself went to stay in a forest divisional headquarters away from Gangtok. It was an old fashioned bungalow which was in fact the headquarters of the Scottish Mission that brought education to the girls in the state and established health dispensaries. My jungle sojourns were greatly restricted then. Then came the border tensions. Defense forces guarding the frontier just 30 kilometers away from Gangtok required large numbers of poles for bunkers. Rhododendrons, which happened to be the principal species in the Gangtok-Nathula area, unfortunately came in handy. In less than six months a good tract of climax forests of rhododendrons was wiped out. Queen (Gyalmo) Hope then made her presence in the country. Her interest in nature conservation further strengthened the hands of her husband Chogyal P. T. Namgyal, who was himself an ardent conservationist. He was the reincarnate of his Uncle Chogyal Sidkeong Tulku, who happened to start the Forest Service in Sikkim in early 1900.

Tse Ten Tashi, an ardent plantsman, happened to be the Private Secretary to the Chogyal. Our family ties went as far back as late 1800 by the way of blood brotherhood. We both, being close associates of the Chandra Nursery at Rhenock where ancestors of Tse Ten Tashi had their estates, found it came in handy for close interactions. His closeness to the Palace on one hand and family ties with the horticulture-minded Pradhan families on the other, was, in fact, a happy augury to boost the importance of Sikkim's flora.

|

|

Tse Ten Tashi and

Rhododendron dalhousiae

Photo courtesy of Keshab C. Pradhan |

At this crossroads, a scion of the DuPont family, Mary Laird, who happened to be the classmate of Hope Namgyal and who happened to attend the Coronation in 1964, offered a scholarship on behalf of the Wemyss Foundation to pursue higher studies in the United States. They chose forestry as the potential field. I thus landed in Yale School of Forestry along with Shanti and 3-year-old son Kailash. During my stay at New Haven I received a letter from H. L. Larson of Tacoma inquiring the collecting of rhododendron seeds in Sikkim. Since I had one more year to go, I suggested that he should write to Tse Ten Tashi. Mr. Larson passed that letter to Britt Smith who pursued the matter further.

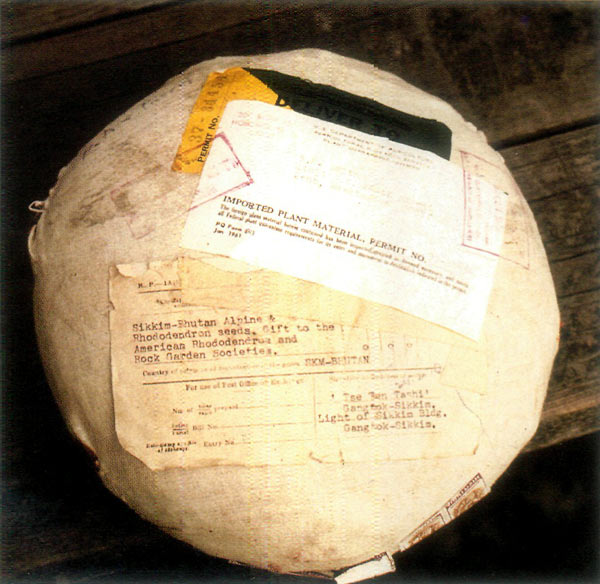

It was one bright morning in 1970, when Tse Ten Tashi, with his usual jest, stepped into my office at the Secretariat where I was the Conservator of Forests heading the Department. An amiable couple accompanied him. They were introduced as Jean and Britt Smith, interested in rhododendrons of Sikkim. It was a fruitful meeting. We suddenly got wiser and saw the importance of their conservation. Tse Ten Tashi and myself spent good hours with the Chogyal and the Gyalmo to discuss the need and modalities for conservation of Sikkim's rich natural heritage, especially rhododendrons. Khangchendzonga National Park and the Alpine Plant Sanctuary were the immediate outcome. Tse Ten Tashi was then retired from service. He had time and interest to pursue his chosen field. We happened to meet or communicate almost every day. Tse Ten Tashi was a workaholic. With any wild thought, he would pop in at any odd hour to share with my father and me. Nathula area, on Sikkim-Tibet frontier, was his favorite hunting ground where we visited many times in a year. All the time I would find him collecting seeds of all odd plants while I occupied myself in my forestry activities. I just did not bother to find what he was doing with those seeds. I often remember many a happy afternoon when we took shelter from pouring rains inside a cave at Kyangnosola Alpine Plant Sanctuary. We afterward named it Tse Ten Tashi Cave. (The rhododendron seeds were sent to the Tacoma Chapter of the American Rhododendron Society.)

|

|

The first shipment of seeds from Sikkim

to the American Rhododendron Society. Photo courtesy of Keshab C. Pradhan |

This peaceful hinterland saw political upheavals in 1973. Queen Hope left Sikkim. At that difficult time Jean and Britt came with a group of 24 ARS members of various interests and ages. They choose to trek in western Sikkim along the Sikkim-Nepal frontier, as other areas were prohibited then. P. K. Basnet and myself received the group at the Sikkim frontier. Camp was hastily made in a jungle cattle shed. The animals had to fend for themselves elsewhere for the night. It was a delightful evening around a campfire with songs and dances. We had recruited about six schoolboys as camp followers. Many years later I was pleasantly surprised when a young man, highly placed in the political hierarchy, came to me to say his happiest moment was in accompanying the group and how we tipped them heavily while departing at Jorthang. I don't exactly remember though.

|

|

Dr. Forrest Bump

Photo courtesy of Britt Smith |

The day we had to shift the camp from Kalijhar was all slippery downwards. Emilie Cobb could not make it. A large bamboo basket was improvised as a seat and an able bodied shepherd carried her down the hills, her hat decorated with all the wild flowers. Dr. Forrest Bump with all his cameras and gadgets hanging around him and the tall jovial figure of Clive Justice stood out in the wilderness. Dr. Simons was always handy for any medical aid. At Gangtok they stayed at the Norkhil Hotel. It was the only hotel worth the name. They had a dinner with the Chogyal at the Palace, though in a subdued atmosphere because of political changes. Shanti, Tashi Densapa and myself were there. Next afternoon the team called on B. S. Das, then the Chief Executive, to whom the members presented a note of thanks and urged him to use his good offices to protect the rich heritage.

|

|

His Majesty Palden Thondup Namgyal and members of the

ARS and the Rhododendron Species Foundation, the first tour group in Sikkim, May 1974. Photo courtesy of Britt Smith |

By the time the group had left, rhododendron mania had come to stay in Sikkim. Sonam Lachungpa soon joined the Forest Service. Having been shaped e Ten Tashi and having come from the rhododendron rich valley of Lachung where his father served in the forest department, he was truly a plantsman. Through him I had implemented many schemes in the field of rhododendron and nature conservation.

|

|

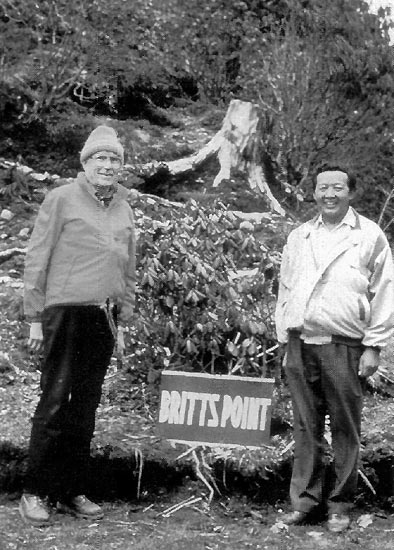

Sonam Lachungpa and

Britt Smith in

Kyangnosla Rhododendron Sanctuary, Britt's Point, May 1992. Photo courtesy of Keshab C. Pradhan |

We were novices to the new political setup. Nevertheless we pressed with all vigor and doggedness demarcation of rhododendron sanctuaries, creation of Khanchendzonga National Park and Kyangnosla Alpine Plant Sanctuary. They were given legal status with the new Forest Conservation Act.

|

|

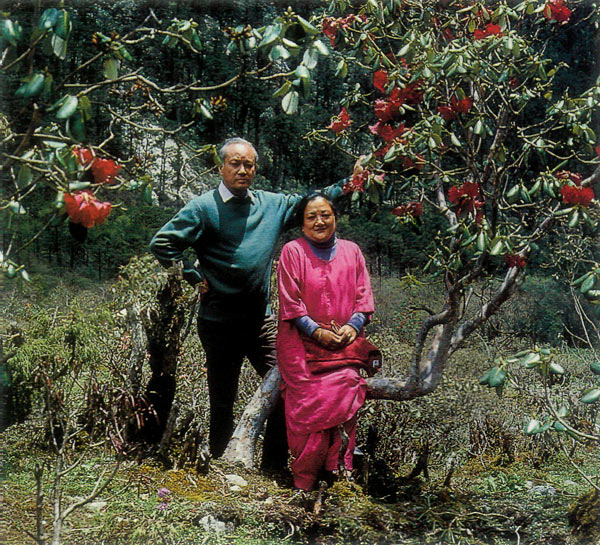

Keshab and Shanti Pradhan

Photo courtesy of Keshab C. Pradhan |

Tse Ten Tashi passed away late in 1972. I left the Forest Service and switched on to the Indian Administrative Service, though holding charge of it as Secretary to the Government for some years. Then came the opportunity for Shanti and myself to attend the Rhododendron Species Foundation Symposium and ARS Annual Convention in 1985. We came closer to Jean and Britt and greatly exposed to the world of rhododendrons. It also helped us to renew our old acquaintances. Britt visited us again in 1990 as guest of the Department of Tourism, Government of India. He could visit prohibited areas like Yumthang and Tsomgu as special guest to advise us on rhododendron studies, preservation and of course to see whether rhodo-eco-tourism can be initiated. This was the beginning. He could highlight the importance of rhododendrons as Sikkim's prized heritage and their need for conservation - a tourist attraction to the mandarins in both Sikkim and Delhi. Relaxing the entry permits for the foreigners to visit these areas followed. The group that Britt led in 1992 was the first to get permission to visit the prohibited areas like Yumthang, Tsomgu. Dzongri was, of course, opened for trekking and mountaineering some years ago. The visit greatly enthused Sonam and other officers in the Forest Department then headed by P. K. Basnett.

We were again fortunate to have Clive Justice in the early 1990s under the Canadian Executive Service Organization to advise and assess visitors facilities and sites as to the readiness to receive tour groups of rhododendron, orchid, alpine plant, butterfly, bird, and nature enthusiasts from abroad. During his stay he initiated formation of Sikkim Rhododendron Society and its affiliation with the ARS as the J. D. Hooker Chapter. The chapter was, in fact, formed by the 1974 group while at Sandakpu in West Bengal in India. We were greatly honored to get its recognition, a result of the sincere efforts of Clive. The recognition gave us further impetus to pursue our goals. I happened to glide in the bureaucracy holding portfolios as finance, tourism, home, industries, and finally to head the state administration. Throughout I kept myself in touch with the Forest Department and encouraged them to develop and preserve the rhodos. Sonam then visited, as guest speaker at the ARS 50th Annual Convention at Portland, Oregon. Publication of the book Rhododendrons of Sikkim Himalayas by Sonam and Udai Pradhan was largely sponsored by Sikkim Nature Conservation Foundation. So it was Britt who exposed us to the exciting world of rhododendrons. This made us know and understand better our own heritage. We may not have come up to his expectations but can possibly say we have made Sikkim the centre of rhododendron activity in the Himalayas. Today the government has recognized the importance of rhododendron preservation and development. A Rhododendron Test Garden at Kewsey at Lachung has been approved in principle. A display Rhododendron and Azalea Garden at Bulbuley near Gangtok is in the cards. Forest Nurseries are devoted to raising large-leafed rhodos for planting along the highways and landscaping. We are on a hunt for rhododendron species and provenance especially in Rhododendron arboreum to plant in warmer areas. Vireya rhododendrons have been introduced from New Zealand. They are doing exceedingly well in warmer climates, including my garden at an altitude of 3,500 feet (1050 m) below Gangtok where the minimum and maximum temperatures range between 10°C and 30°C. Evergreen azaleas from Nuccio's in California, Stubbs' in Oregon, and also from New Zealand and Belgium have been introduced. Out of over 150 cultivars tested, a couple of dozen have proved excellent in the Himalayan foothills. They have become very popular in gardens in Nepal, Bhutan and northern states of India, including Sikkim. Wayside strains of Sikkim azaleas are the latest garden craze here.

We just concluded a nation-wide forestry workshop on research priorities. In Sikkim the rhododendrons have figured prominently in the research poll. Eco-restoration of Gangtok-Nathula Road, once the home of rhododendrons, is in the cards. Large-leafed rhododendrons would be the principal species and perhaps natural regeneration would occur. Hybridizing programs are proceeding to develop tender cultivars to suit Gangtok and similar climate, where the concentration of population demands quality plants for the home, and to pass on the mantle to the younger generation to pursue the cause of rhododendron exploration, conservation, and development with renewed vigor. Gardens and landscaping are in the offing. We are in fact looking for serious students in pursuit of these studies with certain research grants. We are also hopefully looking for a benefactor to purchase a rare original book of Rhododendrons of Sikkim Himalayas by Hooker (1854) and as a gift to our Society. It is in private hands and likely it will find its way elsewhere. Five thousand dollars or so is a tall figure but perhaps worth a try.

Our hope and dream now is to hold the Himalayan Rhododendron Exposition by year 2005. It is to salute the millennium that brought rhododendrons into prominence as a garden plant and also pass on the mantle to the younger generation to continue pursuing the goals with renewed vigour.

Keshab Pradhan, a member of the J. D. Hooker Chapter, authored the article "New Areas Open to Visitor in Sikkim" in the fall 1998 issue of the Journal.